I. Richard Ploss, J.D., CPA, CFP®, TEP, is counsel to Porzio, Bromberg & Newman P.C. and a member of the firm’s trusts and estates department. He concentrates his practice primarily on estate planning for high net worth individuals and their businesses, estate administration, probate litigation, and fiduciary income taxation in New Jersey and throughout the East Coast. He frequently publishes articles and speaks on trust and estate matters.

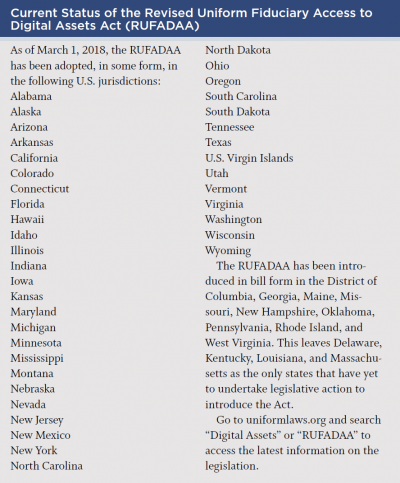

Perhaps one of the most significant non-tax developments in estate planning over the past few years has been the promulgation of the Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act, Revised (2015), or “RUFADAA,” sometimes also referred to as “the Act” by the Uniform Law Commission and the subsequent adoption of the law by 38 U.S. jurisdictions.

The RUFADAA is remarkable in that for the first time, property law recognizes the existence of digital property as a property right that can be managed, conserved and, in certain instances, accessed by third parties, in much the same manner in as other rights in real and tangible personal property.

The formal recognition of this property right imposes an obligation on financial planners to consider digital assets as an integral part of clients’ estate and financial plans. It should be noted at the outset that the RUFADAA does not confer property ownership rights on fiduciaries or on individuals who have access to such assets.

This article will endeavor to introduce (or reintroduce) financial planners to digital assets and to educate them as to how to advise clients in light of the rules contained in the RUFADAA. With this objective in mind, the first part of this article will introduce planners to the RUFADAA and some of the key provisions that provide a framework for advising clients with regard to digital assets. The second part of this article will focus on the some of the strategies that planners may wish to utilize as part of a client’s estate plan.

Words of Caution

A couple of words of caution, before we begin our journey. First, this article will not discuss the impact of any federal law or state criminal or privacy law as it applies to digital assets.1

Second, like most uniform laws that are promulgated by the Uniform Law Commission (such as the Uniform Probate Code and Uniform Trust Code), state legislatures are free to pick and choose which sections they wish to enact and intentionally omit. Thus, in applying any of the information in this article to client planning, planners should ensure that a particular provision is applicable under the state-adopted version of the RUFADAA. For example, although the RUFADAA defines a “fiduciary” to include a court-appointed conservator, New Jersey’s version of the RUFADAA specifically excludes a conservator from the definition of a fiduciary.

Admittedly, because the RUFADAA is a relatively small act (21 sections in total) the differences should be minor. Nevertheless, planners should be sure to check for any such differences between the RUFADAA and the final law enacted in their jurisdiction so as to ensure that the planning is relevant.

Part 1: Understanding the RUFADAA

As discussed previously, the RUFADAA is divided into 21 sections. Section 2 contains the definitions of important terms that are used throughout the Act. The following represents a list of the key definitions that will appear throughout this article:

Digital asset: Section 2(10) of the Act defines a “digital asset” to be an “electronic record of which an individual has a right or interest.” The comments to the Act state that the following is included in this definition:

(a) information that is stored on a user’s computer and other digital devices;

(b) content uploaded on websites; and

(c) “rights in digital property” (designed to be a catchall for all other property not specifically defined under the Act).

Thus, a digital asset would include accounts, documents, information, records, and photos that are accessible primarily by an individual’s access via an electronic device (which would include tablets, smart phones, personal computers, Chromebooks, and Macintosh computers).

This definition would include email accounts, electronic communications, social media accounts (such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter), blogs, cryptocurrencies (such as Bitcoin, Ether, Litecoin, and Ripple), photos and videos posted to the internet, websites, online purchasing/sales accounts (such as Amazon, Craigslist, EBay, PayPal, and catalog accounts), music subscriptions (such as iTunes, Spotify, and Pandora), sports gambling accounts, electronic medical records, documents and records stored to the cloud (through Carbonite, Barracuda, iCloud, and Microsoft OneDrive), movie services (such as Netflix and Hulu), reward programs (for airlines, credit cards, and hotels), voice recordings, contact lists, calendars, text messages, and electronic magazine and newspaper subscriptions. It would also include data and documents stored on the hard drive of a computer, tablet, or smart phone.

In summary, just about anything and everything that an individual can access through a computer, smartphone, tablet, or e-reader will fall within the definition of a digital asset. However, it should be noted that in the case of accounts held at financial institutions, such as banks and brokerage firms, the rights in the digital asset do not extend to the underlying asset (i.e., the cash or securities), and the RUFADAA should not be construed as permitting a fiduciary to engage in a transaction with the underlying assets held at the financial institution.2

Custodian: Section 2(8) of the Act defines a “custodian” to be a “person3 who carries, maintains, processes, retrieves, or stores a digital asset of a user.” This definition is broad enough to include all third-party providers of accounts or services on the internet.

User: Section 2(26) of the Act defines a “user” to be a person who has an account4 with a custodian.

Fiduciary: Section 2(14) of the Act defines a “fiduciary” to be an original or successor personal representative (of an estate), conservator/guardian, agent (attorney-in-fact), or trustee.

Terms of service agreement (TOSA): Section 2(24) of the Act defines a TOSA to be “an agreement that controls the relationship between a user and a custodian.”

Applicability and Scope of the RUFADAA

Section 3 of the RUFADAA specifically states that the Act applies to: (1) an agent or attorney-in-fact acting under a durable power of attorney executed before, on, or after the effective date of the Act; (2) a personal representative (whether under a will or intestacy) acting for a decedent who died before, on, or after the effective date of the Act; (3) a court-appointed conservator (or guardian) appointed before, on, or after the effective date of the Act; and (4) a trustee acting under a trust created before, on, or after the effective date of the Act.

Most importantly, planners need to understand the Act does not apply to the digital assets of an employer used by an employee in the ordinary course of the employer’s business.5 Although this is conceptually easy to understand and apply to situations where an employer purchases the digital asset and only makes it available to the employee on an employer-provided computer, tablet, or smart phone (in which event the digital asset is clearly an employer-owned digital asset), the situation could become more contentious and uncertain when an employee purchases a digital asset for his or her personal use and downloads it onto an employer-provided computer, tablet, or smart phone. To avoid any potential issues, planners should advise clients not to download “personal” digital assets onto employer-provided devices. Instead, all such digital assets should only be accessed through a client’s personal device.

How the RUFADAA Works

Section 4 of the Act provides details on how a fiduciary may obtain disclosure from a custodian as to the existence of a user’s digital assets and potential management rights over such assets.

Before beginning this analysis, four important points need to be noted. First, the user has the ultimate decision as to whether a custodian should disclose to a fiduciary the existence of and access to the content of a user’s digital asset. The user may decide that he or she wants his or her fiduciary to have full disclosure about the existence of and access to such digital assets. It should be noted, however, that in the case of a conservatorship/guardianship judicial proceeding, a court may decide to grant the conservator/guardian the right to access a user’s digital assets. In such an event, one can actually say that the user did not have ultimate control over fiduciary access. I would recommend that any court order appointing a conservator/guardian contain specific language granting such a fiduciary the right to full disclosure and access to a user’s digital assets.6

Second, absent a direction from the user to the contrary, a fiduciary has the right to demand that the custodian provide the fiduciary with a “catalogue of electronic communications” sent by or received by a user.7 The Act defines a “catalogue” to be information that “identifies each person with which a user has had an electronic communication, the time and date of the communication, and the electronic address of the person.”8 Note that the catalogue does not include the content of the communications.

Third, the user has the right to grant a fiduciary access and management to only certain digital assets and not to all digital assets in which the user has a property right. In certain circumstances, this cherry-picking over disclosure and access may be very important to users.9

Finally, it should be noted that even if a fiduciary is granted access to an account or digital asset, a user’s fiduciary does not acquire greater access rights in the digital asset than what the user had.10

Terms of service agreement (TOSA). Under the RUFADAA, a custodian’s TOSA is the starting point for any analysis of a user’s interest in a digital asset. Written in a very abstruse and complex manner, most users usually click “agree” and accept the TOSA so that they can enjoy the benefits of the asset. In addition to defining the rights, responsibilities, and potential liabilities for violation of the terms (just as any contract does), the TOSA contains a default set of rules regarding access to assets during the user’s lifetime and following the death of the user.

The TOSA is generally drafted in such a manner to be advantageous to the custodian to the potential detriment of the user. Many TOSAs specifically state that any information posted by the user becomes the property of the custodian, who is then free to use it in any manner the custodian may deem appropriate (this is generally the case with almost all social media accounts such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat.) Still other TOSA agreements are drafted in such a manner of a licensing agreement, which grants the user a right to the digital asset until the user’s death at which time the user’s rights terminate (this is generally the rule with e-books such as Kindle, and music sharing services such as Spotify, Pandora, and iTunes, although an iTunes family-share plan may provide a user with a way around this limitation).

Finally, almost all TOSAs generally restrict access to the digital asset to the user during the user’s lifetime and prohibit third-party access following the user’s death. As a result, planners need to advise clients that absent some affirmative action, the terms and provisions of the TOSA will govern whether a custodian may grant a fiduciary access to the user’s digital asset. It has been my experience that almost all TOSAs will never grant any third-party access to a user’s digital asset. Therefore, a client who takes no action will generally never be able to grant a fiduciary access to the digital asset.

The RUFADAA provides that if a user’s estate planning documents (i.e., durable power of attorney, last will and testament, and/or trust governing instrument) or a court order explicitly grant a fiduciary the power to access a digital asset, the provisions of the TOSA will no longer prevail and the custodian must grant access to the digital asset to the fiduciary. A fiduciary will need to provide the custodian with copies of governing instruments and other supporting documentation that evidence a fiduciary’s authority to access the digital asset. Generally, this will consist of a copy of the governing instrument and any court-provided documentation, such as letters of authority/letters testamentary, a copy of the user’s death certificate, or a court order.11

Online tool. At the request of certain custodians, the RUFADAA creates a third mechanism for users to grant or withhold fiduciary access to a digital asset through what is referred to as an “online tool.” Section 2(16) of the Act defines an online tool to be “an electronic service provided by a custodian that allows the user, in an agreement distinct from the [TOSA] … to provide directions for the disclosure or non-disclosure of digital assets to a third person.”

A user’s direction to grant or not grant access to a third party as provided in an online tool will prevail over the TOSA or any direction contained in a user’s estate planning documents. Therefore, it is theoretically possible for a user to grant access to the user’s digital assets to a named fiduciary in an estate planning document but override this authority on an asset-by-asset basis by either designating someone else (need not be the fiduciary named under his or her estate planning documents) or directing that no third party is to have access to the digital asset. As of the date of this article, I am only aware of two custodians—Facebook and Google—that offer an online tool option. It is conceivable that in the future more custodians may do so.

Finally, planners need to understand that even if a user grants a fiduciary access to his or her digital assets, the RUFADAA grants the custodian an option as to the form of access that it may grant to the fiduciary. Under the Act, a custodian may grant a fiduciary (1) full access; (2) partial access; or (3) a copy of the record that comprises the digital asset (usually in the case of email access).12 To defray the cost associated with making such disclosure, The RUFADAA also authorizes a custodian to assess a reasonable administrative charge, which will need to be paid by the fiduciary.13

Part 2: A Step-by-Step Process to Address Digital Assets

For an increasing number of clients, digital assets are rapidly becoming a very important part of estates for both financial and sentimental reasons. This trend may accelerate in the years ahead as more goods and services are available online and many traditional brick-and-mortar establishments, such as financial institutions and retailers, continue to close their physical spaces and rely more on an internet presence.

To prepare for this migration, planners should be advising clients to implement systems to track digital assets. Sadly enough, many clients have not taken any action at all to address this issue and when they have taken such action, their systems are not robust enough to match their needs. The following section provides a step-by-step program that planners may wish to consider implementing when addressing digital assets as part of a client’s estate planning process.

Step 1: Identification. Identify whether a particular client has a digital asset presence. This can be accomplished through the use of a questionnaire planners can have a client fill out (in which event the planner should review the questionnaire in person with the client), or the planner can conduct an in-person client interview using the questionnaire as an intake form.

Step 2: Education. If the planner determines that the client has significant digital assets (remember that the dollar value of digital assets is only one measure of value; planners should also weigh a client’s sentimental value assigned to assets such as photos and voice recordings), the planner should educate the client about the RUFADAA. The information in this article can serve as a good starting point for that discussion.14

Step 3: Ascertain the client’s goal with regard to digital assets. After educating the client about the RUFADAA, the planner should consider assisting the client to determine which digital assets in his or her “portfolio” the client wishes to grant third-party access to and which ones the client would prefer not to grant such access. For those digital assets to which the client wishes to grant third-party access, the planner should assist the client in determining whether a fiduciary should have general access to the asset and which assets the client would prefer to grant access to a different third party. If feasible, the planner can help the client ascertain whether an online tool is available for these latter types of digital assets. All of this should be documented as part of the client’s financial plan.

Step 4: Estate planning document revisions. The planner should then recommend that the client confer with his or her estate planning attorney to determine whether the client’s existing estate planning documents adequately address digital assets access. (Although planners can review a client’s estate planning documents to make this determination, it still makes sense to let legal counsel make the final determination as the planner does not want to face a complaint for practicing law.) With the client’s permission, the planner can forward all information obtained from this process described—including the planner’s written report—to the legal counsel to make the process more efficient.

Step 5: Create and maintain a digital asset inventory. Finally, planners should encourage clients to create and maintain an inventory of their digital assets. This may be the most difficult step in the planning process as many clients continue to create new digital assets by signing up for new online accounts or registering on new websites without taking the time to add each new digital asset to the inventory.

The following represents a sample of some methods I have seen clients employ to address the inventory issue:

The master password list. For most clients, a master password list seems to be the method of choice. Clients generally maintain a manual notebook system in which they write down the name of the digital asset provider (for example, their bank, Facebook, Google, etc.) and the password to access each asset in a paper notebook. This can serve as a great starting point, but many clients forget to add passwords as they create new digital assets. This can lead to the list becoming outdated. In addition, many clients fail to disclose to third parties the location of the password notebook so when the need arises for the book, it generally cannot be found.

Other clients maintain their digital asset lists and passwords on the notepad program on their personal computers, tablets, or smart phones. While this may assist in locating the actual list, it could be a security risk if unwanted third parties obtain the list. Still another issue may arise if access to the computer, tablet, or smartphone is password protected and no third party knows the password.

Password managers. Commercial password manager programs have proliferated as tools to generate safe passwords that minimize hacking and to remember the passwords for each custodian’s portal. Vendors charge monthly fees to use these programs. Examples of such programs include Dashlane, 1Password, LastPass, KeePass, and RoboForm. Clients who use these services will generally be more likely to keep information current (in order to keep their sanity).

Some password manager programs allow users to share their log on credentials with trusted persons. Unfortunately, this can present problems if the individual with whom a client shares such information should have a falling out with the client or if such person should decide to become an invidious thief of such information. Still another issue can arise if third-party malefactors should hack the password manager’s server (I’m not aware of any such hack, but it theoretically could happen).

Digital estate planning services. Finally, in the past two years, commercial services have sprung up to store a user’s digital asset information (generally on a secure server) and to provide the same to attorneys and family members of users. Examples of such service providers include Directive Communications Systems, Estate Map, AssetLock, My Wonderful Life, and SecureSafe.

These services can be quite helpful in assisting fiduciaries and estate planning attorneys in trying to locate digital assets. Some produce reports that can be shared with a client’s planner or attorney during the user’s lifetime. Perhaps best of all, some do not store passwords for financial accounts but rather provide a roadmap to assist fiduciaries and their planners in locating digital assets. Most vendors charge a one-time setup fee and then assess an annual fee. Although the fees charged are reasonable (especially when compared to the legal costs of having a law firm bill by the hour to locate such assets following the death of the client), some clients do not want to spend the money, even though this could be part of a client’s risk management program.

Like password managers, there is always a risk that the service’s server could be hacked (but again, I am not aware of any such attacks). In addition, while most service providers encourage users to annually update their catalog of assets, there is always an inherent risk that a client may procrastinate and never update his or her records with the provider. However, if a financial planner or attorney is included as a contact on the account, it is possible for the planner to go through the annual update process with the client during a scheduled review meeting.

Conclusion

Digital assets are becoming more important in a client’s financial plan. The RUFADAA represents the law’s recognition of this trend by recognizing digital assets as a property right that needs to be managed and conserved. This article has endeavored to explain how the RUFADAA accomplishes this task and what steps financial planners may take today to integrate digital asset management into a client’s estate plan.

Endnotes

- Planners should be aware of and consider the impact of the Electronics Communications Privacy Act (also known as the Stored Communications Act, which may be found at 18 U.S.C. §2701 et. seq.; the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which may be found at 18 U.S.C. §1030, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1986 (HIPAA) Pub L. 104-191). The impact of state law should be considered as well. The official comment to Section 3 of the RUFADAA acknowledges this impact by specifically stating that the RUFADAA does not substantively change other laws such as agency, banking, contract, criminal, fiduciary, privacy, probate, property, security, or trust law.

- See official comment to Section 2 of the RUFADAA. It should be pointed out that other law (such as probate, property, and trust law) may confer such a right on a fiduciary.

- Section 2(17) of the Act defines a “person” to be “an individual, estate, business, non-profit corporation, government or governmental subdivision, agency or instrumentality or other legal entity.”

- Section 2(1) of the Act defines an “account” to be “an arrangement under a terms of service agreement in which a custodian carries, maintains, processes, receives, or stores a digital asset of the user or provides goods or services to the user.”

- See Section 3(c) of the RUFADAA.

- The official comment to Section 14 of the Act specifically supports this assertion.

- See RUFADAA Sections 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14. Note that the fiduciary will need to provide the custodian with certain documentation as part of this request.

- See RUFADAA Section 1(4).

- In many of my presentations on digital assets, I’ve used as a hypothetical example a situation in which a married user designates his or her spouse as a fiduciary (i.e., attorney-in-fact under a durable power of attorney and/or executor/personal representative of his or her estate) and wants to grant such a fiduciary access to all digital assets except for any online dating service account.

- See official comment to Section 5 of the Act.

- See Sections 7 through 14 of the RUFADAA for further enumeration.

- See RUFADAA Section 6.

- See RUFADAA Section 6(b).

- For additional reading material, consider the following article I wrote in question-and-answer format (pbnlaw.com/media-and-events/article/2017/09/what-new-jersey-residents-need-to-know-about-digital-assets-under-new-jerseys-new-digital-asset-act/?page=1994). The article is focused on New Jersey’s version of the RUFADAA, but much of the information will be applicable to clients domiciled in other states that have adopted the RUFADAA.