Journal of Financial Planning: April 2014

The growth of the older adult population in America is presenting great opportunity and great challenges to the financial planning profession.

On one hand, older adults disproportionally have wealth; as a group they represent 13 percent of the current U.S. population, but hold 21 percent of the nation’s wealth. This statistic from the National Institute on Aging underscores the opportunity for increased financial planning services to older adults now and in the coming years. According to the Pew Research Center, about 18 percent of the U.S. population will be over age 65 by 2030.

On the other hand, a startling 22 percent of older adults over age 71 have some neurocognitive disorder (Plassman et al. 2008). The majority of these disorders are minor, but according to the Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s disease will strike about 8 million Americans age 65 and older by 2030 (a rise of 60 percent from 2010), underscoring the increasing challenge of providing financial services to older adults.

Aging Adults at Risk

The health and social services industry has come at the problem of vulnerable older adults at risk of financial exploitation in two ways: (1) the rise of a definition of financial capacity; and (2) increased knowledge of and attention being paid to elder justice and elder abuse. Generations, the Journal of the American Society on Aging, had two recent issues devoted to financial capacity and elder justice, neither of which presented an integration of the two sub-fields. The goal of this article is to describe these two sub-fields of gerontology and to relate these to the work of financial planners.

Financial Capacity

A big distinction exists between what financial capacity is and how it can be understood and used by financial planners. Financial capacity refers to a number of financial domains that range from basic to complex. Daniel Marson, professor of neurology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and his colleagues (Marson et al. 2012) have outlined nine domains of financial capacity:

- Basic monetary skills

- Financial conceptual knowledge

- Cash transactions

- Checkbook management

- Bank statement management

- Financial judgment

- Bill payment

- Estate planning/wills

- Investment decision making

Marson’s research has focused on how neurocognitive disorders affect domains of financial capacity. For this article, let’s examine this with regard to financial judgment; making a decision about how to invest one’s money. Fifty percent of older adults with mild Alzheimer’s disease were fully incapable of making financial judgments as measured by the Financial Capacity Inventory (FCI). Created by Marson, the FCI uses a neutral, non-person-centered investment problem to measure financial judgment. Marson’s results clearly indicate that having neurocognitive problems such as early Alzheimer’s disease poses an increased risk that the older adult does not have capacity.

Elder Justice Movement

The elder justice movement, from a societal perspective, is an effort to prevent, detect, treat, and intervene in cases where elders are being exploited and abused. The justice aspect is the recognition from the U.S. Congress with passage of the 2009 Elder Justice Act, that older adults have the right to be free from abuse, neglect, and exploitation.

According to Acierno et al. (2010), “In the U.S. an estimated 5 percent of elderly people have fallen victim to financial exploitation, second only to theft and scam cases.” Another study (Beach et al. 2010) estimated that 10 percent of all older adults experienced financial exploitation since turning 60 years of age. States are ramping up efforts not only to protect older adults from financial exploitation, but also to better prosecute those who exploit older adults.

Integrating Financial Capacity and the Elder Justice Movement

Lichtenberg et al. (2013) reported results of a nationally based study, which demonstrated that psychological vulnerability made older adults nearly three times more likely to be the victim of a scam. The research study involved 20 experts from across the country, including three financial planners, who created a new interview-based screening tool regarding financial decisions and judgments for financial planners, and a more comprehensive tool for health and mental health professionals. For the financial planner, the most important question comes down to how to advise this individual at this particular time, with this particular decision.

The tension that exists between protecting older adults with diminished capacity and respecting and promoting autonomy in older adults who have capacity is ever-present. Financial planners can take four major steps to better serve vulnerable older adults:

- Better recognize neurocognitive disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.

- Understand the basic tenets of decisional abilities for a financial judgment or decision.

- Create a relationship with a geriatric health care expert and an expert in financial capacity.

- Create a relationship with the local adult protective services agency to more effectively report cases of financial exploitation.

Recognizing Early Alzheimer’s Disease

Because financial planners are not health care professionals, we do not recommend that they learn cognitive screening or other direct assessments of cognitive abilities. Instead, financial planners can use “behavioral triggers”—patterns of behavior exhibited by an older client that raise suspicion of memory loss or problem-solving declines. Common triggers can be found during direct communication with clients by the planner and/or the staff. These include:

- Missed office appointments

- Confusion about instructions

- Frequent calls to the office

- Repetitive speech and/or questions

- Missed paying bills

- Difficulty following directions

- Trouble with handling paperwork

- Difficulty recalling past decisions or actions

The presence of these triggers is not diagnostic, but should raise suspicion of significant cognitive problems and cause for a discussion of the issue. The client with memory problems may indeed still have capacity for a specific financial decision, but is this appropriate for a financial planner to decide?

Financial Decisional Abilities: A New Model

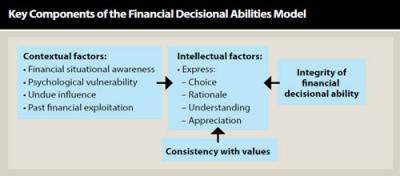

The separate work done on financial capacity and elder justice led us to create an integrated model. The conceptual model we propose here is called financial decisional abilities.

Decisional abilities have long been recognized as the key factors in determining whether or not an individual’s decision (choice) is an authentic and capable one. It combines key contextual and intellectual factors influencing decision-making.

As seen in the flow chart on page 24, contextual factors include financial situational awareness, psychological vulnerability (including loneliness and depression), undue influence, and financial exploitation. Contextual factors are viewed as having a direct influence on the intellectual factors associated with decisional integrity for a sentinel financial transaction.

Intellectual factors refer to functional abilities needed for financial decision-making capacity and include an older adult’s ability to express a choice, communicate the rationale for the choice, demonstrate an understanding of the choice, demonstrate an appreciation of the relevant factors involved in that choice, along with the consistency of the choice with past cherished values.

The intellectual factors, (along with assessing the impact of the contextual factors on the intellectual factors) in the decisional abilities framework are the factors that determine the integrity of a financial decision. The model can serve as a guide for aspects to consider when a vulnerable older adult is trying to make a financial decision.

When a financial planner is concerned about the decisional abilities of the older client, it is recommended that relationships be developed with health care providers who can more thoroughly assess capacity including: (1) whether there is a diagnosable neurocognitive disorder; (2) how completely the older adult displays decisional abilities; (3) whether there appears to be any undue influence; and (4) how the results integrate with specific legal standards that apply to the financial decision (for example, will, versus investment, versus real estate contract). A financial planner may uncover financial exploitation, and it is incumbent on planners to report these to adult protective services agencies so an official elder abuse investigation can be undertaken.

Practical Implications for Financial Planners

For many financial planners, the 65-and-older population makes up a significant portion of their client base. Therefore, it will be increasingly important for planners to be prepared to handle issues involving financial capacity. Planners need to be aware of the potential financial vulnerability of this client segment and prepared to take action to protect and serve them. Here we attempt to provide planners with some of the most important issues and practice management tools to best serve these clients.

Build a network. Financial planners have a broad base of knowledge with which to assist clients with their financial lives. As clients age, issues can extend beyond financial into areas such as housing, care assistance, complex legal issues, and government and other benefits. It is important for planners to build networks of professionals in their geographic area that can be part of the team that serves these older adults as needed. Such professionals can include elder law attorneys, geriatric care managers, home care providers, and medical professionals who can assess financial capacity. The financial planner is in a unique position to quarterback this team of professionals to best serve their clients, becoming invaluable to these clients and their families.

Client relationships. Building trusting, personal relationships with clients is a best practice, no matter the age of the client. However, this becomes even more important when it comes to serving older adults. Financial planners, more than many other professional advisers, have the opportunity to stay in frequent contact with clients. Frequent contact not only builds rapport and trust, but it also allows the planner to know the client on a deeper level, giving the planner the ability to recognize changes in client behaviors and abilities. Establishing a relationship in which the financial planner becomes the client’s partner and sounding board for all financial-related issues can be invaluable when it comes to preventing financial fraud and abuse.

Family relationships. In addition to building relationships with clients, building relationships with clients’ families is important. Financial planners should make a practice of encouraging older adult clients to begin to include trusted family members or friends into their future planning. The invitation to include these additional participants may start with a simple, informal meeting during which the family members meet the planning team without an in-depth discussion of client assets or overall plan. Subsequent meetings can incorporate family members into annual planning meetings or can involve holding a family meeting to cover current and future planning. A family meeting to discuss future/elder care planning would involve discussions around the challenges, alternatives, resources, and experiences the older adult clients may have as they age. This planning allows the clients to maintain control and to express desires related to their money, legacy, housing, and care. Planning ahead for future care can keep the client in control, even if financial capacity issues develop later.

Communication guidelines. Frequent and consistent communication with clients becomes more important as they age. In-person and other verbal communication is not only the best way to build trust, but it is also the best way to keep on top of each client’s situation and to make adjustments as needed. It is a best practice to follow up each client meeting with a written letter outlining discussion topics and action items. The follow-up letter helps ensure the client and planner are on the same page and that there are no misunderstandings. As clients age, it is often a good idea to also follow up phone calls with a short, written summary, especially if the conversation involves numbers or new decisions.

Client database. Every client contact and communication should be documented and tracked in a client database or client relationship management system. Tracking client contacts allows planners to notice trends and changes in client behaviors, especially when there are multiple team members involved. Tracking also provides a history of activity and documents advice to clients over time. The client database also provides the planning team with a place to track outside assets, policies, and advisers for each client—and that can be an invaluable planning tool.

Record-keeping document. It is important for all clients, but particularly for older clients, to have their financial lives organized and documented. Using a single document, either on paper or in an electronic format, to capture adviser names and contact information, all financial accounts, policies, legal documents, medications, etc., can be helpful when/if a time comes when the client cannot remember or communicate this information to others. Financial planners can assist clients in completing such a document, can follow up to make sure it is updated regularly, and can store a completed copy for the client as a back-up to their original at home. Planners should also keep copies of all legal documents and outside account and policy information on file for future planning needs.

Client authorization document. It is now a best practice for financial planners and other professionals working with older adults to use an “authorization document.” This document, which is completed and signed by the client (at a trigger age or earlier if circumstances warrant), gives the planner permission to contact named professionals, family members, or friends if a change in the client’s physical, psychological, or cognitive abilities is suspected. When clients complete and sign this authorization document, it helps avoid privacy issues and provides the planner the opportunity to better serve the client in any circumstance. Presenting the document to clients also provides the opportunity to discuss capacity issues with them before they occur and can assure clients that the planner is prepared to serve them as they age.

Investment policy statement. Financial planners providing investment management services for clients need to be particularly aware of capacity issues that may affect clients’ decision-making abilities. To be prepared, every client should have a signed investment policy statement (IPS) on file. An IPS should detail any important information that is significant to managing the client’s personal investment portfolio, including:

- Target asset allocation

- Risk tolerance

- Timeframe for investment/use of assets

- Goals for the assets

- Liquidity needs

- Account restrictions/preferences

- Any special circumstances that might affect investments

The IPS should be reviewed and reaffirmed at least annually with the client to update for changes in goals and circumstances.

Financial planners need to be prepared to meet the aging population boom and their potential financial capacity issues head on. Developing the right team as well as putting into place the right planning tools, documents, and processes is essential in serving as fiduciaries for our clients—protecting them while doing our best to serve their future planning needs.

Sandra D. Adams, CFP®, is a lead financial planner at the Center for Financial Planning Inc. in Southfield, Michigan, where she serves as the point person for elder care issues. She is a current member of the legal and financial advisory committee and board of visitors at the Institute of Gerontology. She speaks frequently on elder care planning and recently earned a graduate certificate in gerontology from Eastern Michigan University.

Peter A. Lichtenberg, Ph.D., ABPP, is director of the Institute of Gerontology and the Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute at Wayne State University, where he is also a professor of psychology. He is the creator of a 10-item interview scale to help financial planners screen for integrity of financial decisional abilities.

References

Acierno, Ronald, M.A. Hernandez, Amanda Amstadter, Heidi Resnick, Kenneth Steve, Wendy Muzzy, and Dean Kilpatrick. (2010). “Prevalence and Correlates of Emotional, Physical, Sexual, and Financial Abuse and Potential Neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study.” American Journal of Public Health 100 (2): 292–297.

Beach, Scott, Richard Schulz, Nicholas G. Castle, and Jules Rosen. (2010). “Financial Exploitation and Psychological Mistreatment among Older Adults: Differences between African Americans and Non-African Americans in a Population-Based Survey.” The Gerontologist 50 (6): 744–757.

Lichtenberg, Peter A., Laurie Stickney, and Daniel Paulson. (2013). “Is Psychological Vulnerability Related to the Experience of Fraud in Older Adults?” Clinical Gerontologist 36 (2): 132–146.

Marson, Daniel C., and Charles P. Sabatino. 2012. “Financial Capacity in an Aging Society.” Generations 36: 6–11.

Plassman, Brenda L., et al. 2008. “Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment without Dementia in the United States.” Annals of Internal Medicine 148: 427–434.