Journal of Financial Planning: April 2015

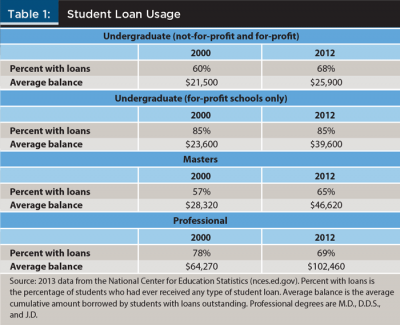

When it comes to paying for college, student loans are indeed the norm, rather than the exception. The majority of undergraduate students in the United States have received some type of student loan, and the average balance of those loans for undergrads in 2012 was $25,900, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

For many young adults, exiting their college years and entering the workforce with sizable debt can be a life-long financial challenge. However, individuals with low income or high debt levels often benefit from income-based repayment plans.

Repayment plans and loan forgiveness programs are scheduled to be expanded in 2015 and could dramatically change decisions about student loan debt. Payment amounts will be based on the ability to pay instead of the level of debt and interest rate.

Families with children planning for college may have an increased need for advice because of the increasing complexity of student loan repayment. This article examines the impact of income-based repayment plans and loan forgiveness on individuals with student loan debt in an attempt to provide financial planners with the information needed to best serve their clients.

The State of Student Loan Debt

Student loan debt rose by 328 percent from $241 million in 2003 to $1.08 trillion in 2013, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The percentage of students with loans and average balances are shown in Table 1. The average amount borrowed in 2012 was $25,900 for undergraduates, and that average amount rises to $46,620 for masters’ students and $102,460 for future doctors and lawyers. Students at for-profit schools borrow at substantially higher levels. Belfield (2013) found that students in for-profit colleges borrow four times as much as students at public colleges with significantly lower repayment rates. McGuire (2012) showed that many students at for-profit colleges are often in a worse financial situation after attending because of the debt burden.

For many students, the financial aid system is confusing and the amount of debt can become unmanageable. Andruska, Hogarth, Fletcher, Forbes, and Wohlgemuth (2014) found that 37 percent of student borrowers were unaware of their amount of debt, and 13 percent of student borrowers incorrectly believed they had no student debt. Fuller (2014) argued that student financial aid has shifted to a confusing array of lending programs that are inefficient and need reform. Unfortunately, there have been few alternatives and little relief for students with excessive student loan debt. Kim (2007) and Minicozzi (2005) found that high debt levels adversely affect graduation rates and influence career decisions. However, a new alternative that determines the payment based on income is rising in popularity.

Income-Based Repayment

Income-based repayment (IBR) of student loans has been available since July 1, 2009.1 These plans calculate the payment amount based on income and family size instead of the standard amortization method using the amount of debt and interest rate. These plans will dramatically reduce the burden of student loan debt for recent and future borrowers.

There have been several versions of these repayment plans, but they share three key characteristics: (1) monthly payments are capped at a percentage of the borrower’s discretionary income, typically 10 to 15 percent; (2) the length of the loan is limited to 20 to 25 years; and (3) any remaining balance at the end of the payment period is forgiven.

IBR plans can be coupled with loan forgiveness available to public service employees to further limit the burden of student loan debt.

Public Service Loan Forgiveness

Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) is a program that forgives the remaining student loan balance after 10 years of loan payments and qualified employment.2 Qualified employment includes full-time employment with a government organization (federal, state, or local), a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, and other nonprofit organizations that provide specified public services.

Graduates with excessive debt are free to pursue lower-income jobs or careers with nonprofits. A portion of higher education costs has been shifted to the federal government. Graduates who are unable to find reasonable employment will not necessarily face a lifetime of poverty. Although there are numerous benefits, borrowers must be aware of the complexities of the programs to fully benefit and avoid potential drawbacks.

How These Programs Work

IBR plans and PSLF are available only to borrowers with federal student loans, such as the Stafford, PLUS, and consolidation loans made under the Federal Direct Loan Program or the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) Program. Federal Direct Loans are issued by the Department of Education. FFELs were issued by financial institutions and guaranteed by the Department of Education, but on March 30, 2010 FFELs were eliminated by the Student Aid and Fiscal Responsibility Act, and the Department of Education became the sole issuer of federal student loans. Parent PLUS loans and private student loans are not eligible for IBR plans or PSLF.

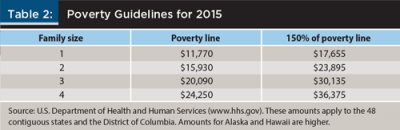

The original IBR plan (IBR “classic”) caps the payment at 15 percent of discretionary income for 25 years.3 Discretionary income is an individual’s adjusted gross income (AGI) minus 150 percent of the poverty line. Using the poverty guidelines in Table 2, a single individual earning $35,000 with a $60,000 loan would have an initial monthly payment of $217.4 Any balance remaining after 25 years of payments (10 years if the borrower works in public service) would be forgiven.

Changes to IBR

For Federal Direct borrowers who took out their first loan after September 30, 2007, the IBR plan (IBR “current”) is more generous.5 Loans issued by other financial institutions through the FFEL program are not eligible.6 Payments are capped at 10 percent of discretionary income, and the term is limited to 20 years. The initial payment for the individual above would now be $145.7

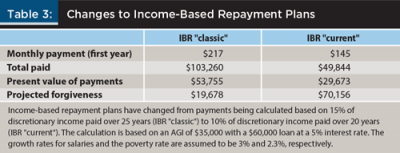

Table 3 provides a comparison of the “classic” and “current” IBR plans. The total amount paid declines by $53,416. The present value cost of the loan declines by $24,082, and the amount forgiven at the end of the loan rises by $50,478. The recent changes to the IBR plan make them much more attractive.

Scenario 1: Public School Teacher

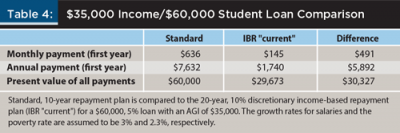

Jordan recently graduated college and accepted a teaching position at a public school with an annual salary of $35,000. He has $60,000 of student loan debt with a 5 percent interest rate.

Table 4 shows the difference between a standard, 10-year repayment, and a 20-year IBR. The IBR reduces Jordan’s first-year payment by $491 per month. The annual savings in the first year is $5,892. The present value of the IBR payments is $30,327 lower than the standard repayment plan.

The IBR plan also caps the payment at the standard, 10-year payment. Regardless of Jordan’s income, his payment will never exceed $636. However, he still has to pay for 20 years (10 years if he is eligible for the PSLF program) or until the loan is fully paid.

Jordan works for a public school and is eligible for loan forgiveness after he has made payments for 10 years through the PSLF program. The total amount paid drops from $49,884 to $20,525 because of the forgiveness. The present value drops by $13,785, and the amount forgiven falls by $681. The present value difference, $13,785, spread evenly over 10 years amounts to approximately $1,378 per year. Essentially, a public service job is worth more than $1,000 more per year than a private sector job.

Scenario 2: Med School Grad

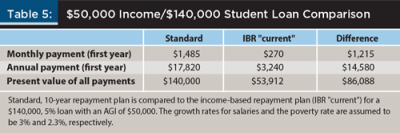

Riley recently graduated medical school with $140,000 in student loans at 5 percent interest. She has accepted a position with a nonprofit organization with an annual salary of $50,000. The difference between a standard, 10-year repayment and a 20-year IBR is shown in Table 5. The IBR reduces Riley’s first-year payment by $1,215 per month. The annual savings in the first year is $14,580. The present value of the IBR payments is $86,088 lower than the standard repayment plan.

Because she works for a nonprofit, Riley is eligible for loan forgiveness after she has made payments for 10 years through the PSLF program. The total amount paid drops from $90,150 to $37,720 due to the forgiveness. The present value drops by $24,676, and the amount forgiven declines by $17,570. The present value difference, $24,676, spread evenly over 10 years amounts to approximately $2,000 per year. In Riley’s case, a public service job is worth $2,000 more per year than a private sector job.

Comparison of Repayment Plans

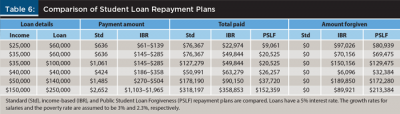

The payment amounts, total paid, and amounts forgiven for a variety of income levels and loan sizes are given in Table 6. The difference in payment methods is obvious. The amount paid using the standard, 10-year payment plan is not affected by income level. Conversely, a borrower with an income of $35,000 will pay the same amount on a $60,000 loan as he or she would on a $100,000 loan using an IBR plan. If the borrower’s income level is low enough, the regular payment amount would be zero. No payment due to low income is considered a regular payment in the calcuation of the foriveness date.

Marriage and Dependents

A married borrower must include spousal income in the calculation of AGI unless the couple files separately on their tax returns. If the couple files separately, the IBR repayment amount will be similar to the amount each would pay if they were single.8 If the couple has a child, the individual who claims the child will reduce his or her payments. Married couples or couples planning to get married where either partner has student loan debt needs to consider their options to minimize their debt burden.

Parents will have lower payments because their poverty line is higher. Returning to the first scenario, Jordan is earning $35,000 and has $60,000 of student loans. Now assume he is the single parent of two children (he had no dependents in the original example). His initial monthly payment declines by $104, and the total paid is $31,246 lower.

A couple with children often compare the cost of child care to the cost of one of the parents providing the child care instead of working. The parent who provides child care will not have to pay on his or her student loan if their income is low or zero. The other parent will claim the children as dependents and lower his or her student loan payment. If only one parent has a significant student loan balance, the benefit will be substantially higher if that parent provides the child care.

Other Considerations

Payments that are deferred because the borrower is in school or during a grace period do not count as payments for the IBR or PSLF program. Low income may result in a zero payment amount using the IBR calculation. A zero payment due to low income does count as a payment under both the IBR and PSLF program. The IBR payment increases as a borrower’s salary increases, however the IBR payment is capped at the payment for the standard, 10-year repayment plan.

Full-time employment for the PSLF program is defined as an annual average of 30 hours per week. If the employment contract is for eight months of a 12-month period, an average of 30 hours per week for the eight-month period is considered full time. A person with two or more part-time jobs of qualified employment is considered full time if the combined employment averages at least 30 hours per week.

The IBR payment may not cover the interest due. In the first three years of IBR payments, the missed interest amounts are forgiven. Beginning in the fourth year, if

IBR payments do not cover the interest due, the interest accrues but is not capitalized into the loan unless payments are switched from IBR.

Finally, consider tax implications. The amount forgiven at the end of an IBR program is treated as taxable income, whereas the amount forgiven under the PSLF program is not considered taxable income. A borrower using the IBR program must prepare for the tax bill of the forgiven amount in the final year.

Conclusion

IBR plans and the PSLF program have numerous implications. For individuals, excessive student loan debt will not be as problematic as it has been in the past. Borrowers’ payments are not based on the amount of their debt unless their income is above a certain threshold. For borrowers below the income threshold, their payments are based on a reasonable percentage of income. In fact, students may be better off accruing student loan debt instead of credit card or other types of private debt. However, student loan debt generally cannot be discharged in bankruptcy and 20 years of payments is a long time to pay debt.

For persons near the poverty line, student loan debt will have to be repaid only if their income increases substantially. Borrowers are able to push the debt on the government if their student loan decision was a bad one and their income does not rise. Either borrowers increase their income because of their additional education and pay a reasonable payment, or their income is unchanged and no payment is required. The possibility that questionable schools will benefit at the expense of the taxpayers must be monitored.

IBR plans and the PSLF program essentially shift some higher education costs to the federal government. This may be a positive outcome for individuals but the complexity of the method is inefficient. It does little to rein in the rising costs of higher education and is susceptible to fraud. It also increases the deferred liabilities of the federal government.

Currently, IBR plans are only available to those who borrowed directly from the federal government and whose first loan was granted after September 30, 2007. However, the U.S. Department of Education has been directed to expand the program. Proposed regulations are expected in mid-2015 (Carrns, 2014).

Individuals considering IBR plans and the PSLF program must take into account the implications marriage and children have on their student loan debt. Moreover, they may find public service jobs more attractive given that forgiveness is earned after 10 years, and they may be reluctant to switch jobs, particularly public service jobs, after a few years.

Jarrod Johnston, Ph.D., CFP®, is an associate professor of finance at Appalachian State University where he teaches courses in finance and retirement planning.

Ivan Roten, Ph.D., CFP®, is an associate professor of finance in the Department of Finance, Banking and Insurance at Appalachian State University.

Endnotes

- College Cost Reduction and Access Act of 2007, Pub. L. No. 110-84, 121 Stat. 793 (2007).

- United States Code, 2006 Edition, Supplement 5, Title 20—Education, Section 1087e(m).

- College Cost Reduction and Access Act, Pub. L. No. 110-84, 121 Stat. 793 (2007).

- $35,000 – $17,655 = $17,345. $17,345 x .15 = $2,602. $2,602/12 = $217.

- Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, H.R. 4872, 111th Congress, Section 2213 (2010).

- All federal student loans, Federal Direct and FFELs, are eligible for the IBR “classic” plan. To be eligible for the IBR “current” plan, the loan must be originated by the federal government, the borrower’s first loan must be after September 30, 2007, and the borrower must have taken at least one loan after September 30, 2011.

- $35,000 – $17,655 = 17,345. $17,345 x .10 = $1,735. $1,735/12 = $145.

- United States Code, 2006 Edition, Supplement 5, Title 20—Education, Section 1098e(d).

References

Andruska, Emily A., Jeanne M. Hogarth, Cynthia Needles Fletcher, Gregory R. Forbes, and Darring R. Wohlgemuth. 2014. “Do You Know What You Owe? Students’ Understanding of Their Student Loans.” Journal of Student Financial Aid 44: 125–148.

Belfield, Clive R. 2013. “Student Loans and Repayment Rates: The Role of For-Profit Colleges.” Research in Higher Education 54: 1–29.

Carrns, Ann. 2014, August 13. “Help Is on the Way for Repaying Student Loans.” New York Times.

Fuller, Matthew B. 2014. “A History of Financial Aid to Students.” Journal of Student Financial Aid 44: 1–68.

Kim, Dongbin B. 2007. “The Effect of Loans on Students’ Degree Attainment: Differences by Student and Institutional Characteristics.” Harvard Educational Review 77: 64–100.

McGuire, Matthew A. 2012. “Subprime Education: For-Profit Colleges and the Problem with Title IV Federal Student Aid.” Duke Law Journal 62: 119–131.

Minicozzi, Alexandra. 2005. “The Short-Term Effect of Educational Debt on Job Decisions.” Economics of Education Review 24: 417–430.

Learn More

Access the archived Financial Counseling Community call and presentation, “Financial Planning for a College Education,” by Mark Kantrowitz of Edvisors.com, on FPA Connect at fpa.adobeconnect.com/p87ojhjcuw5, where Kantrowitz simplifies the complex world of student aid and student loan options.