Journal of Financial Planning: August 2011

Betty Meredith, CFA, CFP®, CRC®, is director of education and research for the International Foundation for Retirement Education (InFRE). She oversees incorporation of research findings and best practices into InFRE’s Certified Retirement Counselor® certification study and professional continuing education programs to help professionals meet the retirement preparedness and income management needs of clients and employees.

A recent New York Times article posited a question that launched a spirited e-mail discussion among many top American and British retirement professionals in the Society of Actuaries’ (SOA) Post-Retirement Needs and Risks Group. Two 65-year-old identical twins each have the same present value of retirement benefits. One twin will receive that benefit as a lifetime monthly annuity of $4,000 a month. The other is handed the lump-sum equivalent, complete with its myriad accompanying decisions and risks. Which twin would you rather be?

After 22 years of primarily providing employee, client, and adviser education, I find that the 80/20 principle applies to making decisions about investing and planning for the future: 20 percent of the population has the desire and capability to tackle this on their own, and 80 percent wants someone to guide them or do it for them. The 401(k) industry, the Department of Labor, and Congress now endorse automatic enrollment, deferral, and management of participant retirement savings exactly for this reason. Herein lies the problem: making informed retirement income decisions is much more difficult than making retirement accumulation decisions, and millions of pre-retirement and retired Americans are not currently getting the professional advice needed to make these decisions over the next 20 years.

Professionals choosing to work with these millions of middle-mass and middle-mass-affluent clients will be called on not only to generate retirement income but to optimize the insufficient resources these clients bring to the table, by making sure key risks such as longevity, inflation, health, and long-term care are first addressed.

Sounds like a job for software.

2003 and 2009 Retirement Software Studies

In 2003 the International Foundation for Retirement Education (InFRE) co-sponsored a study with the SOA and LIMRA1 to evaluate retirement planning software programs. The software included the retirement planning components of popular programs used by financial planners, the proprietary software of several financial services firms, and key consumer programs available via the Internet. The study applied the data of 6 hypothetical case studies to all 19 programs and assessed the following:

1. The capabilities and usability of the software

2. Approaches used to address key retirement risks

3. Recommendations regarding

a. Longevity

b. Income sources

c. Investments

d. Income distribution

e. Expenses

f. Long-term care

The study demonstrated that most programs treat post-retirement planning as an extension of accumulation planning. The ability to model income solutions was far less than what planners needed to optimize a retirement income plan and also address the key post-retirement risks most mid-market pre-retirees and retirees face. Results varied widely from one program to the next. In short, the authors recommended that planners employ multiple programs to flesh out a second—and sometimes third—opinion.

The study was repeated in 20092 using 12 programs and more in-depth case studies. Software was categorized as to whether it primarily addressed investments and portfolio management, how much to save for retirement, or how to manage retirement resources and risks. The goal again was to determine whether the software tools appropriately addressed the modeling needs of retirement professionals to explore a variety of alternatives for creating income plans while managing post-retirement risks. As before, six cases were used to compare the results. This time, however, they were designed to represent the largest 6 of the 12 middle-mass and middle-affluent market segments identified in the SOA’s 2009 Segmenting the Middle Market study,3 and tested for factors such as working past age 65, changes in health coverage, conservative investment allocation, different withdrawal strategies, and using the home as a primary retirement asset.

2009 Study Results

The goal of the 2009 study was to identify the general progress made in dealing with post-retirement risks by software programs since the 2003 study. Did the more recent programs recognize the key risks of longevity, inflation, health, long-term care, and various market risks, and if so, what options were provided to address those risks? In particular, the study evaluated the advice given for:

- When to retire and receive Social Security benefits

- How much should be saved, and whether the savings need was over- or underestimated

- How much can be consumed during retirement

- What to recommend for asset drawdown when savings are insufficient

- Whether to use income annuities to create a floor when needed

- Which assets should be spent down first

- How the investment portfolio should be changed to manage risks and produce income needed

- How well the program provided opportunities to educate the user

- How well retiree health, life, long-term care, Medicare, annuity, and inflation-indexed insurance products are considered

- What is the effect of downsizing a home or paying off the mortgage early versus contributing to a tax-deferred account

- How much the advice differed from other programs

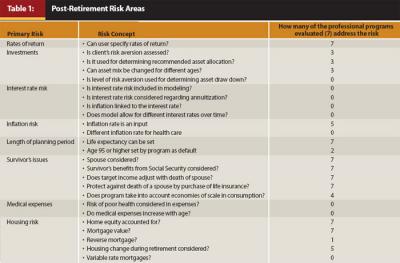

The 2009 study found much progress was made in professional programs, but that there is still room for improvement in key post-retirement risk areas (see Table 1).

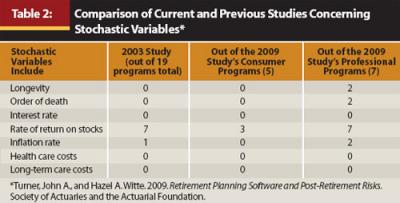

And most of the professional programs still do not allow for stochastic modeling of key post-retirement risks as planners might need (see Table 2).

The researchers also felt the need for best-practice guidelines on the following during input and interpretation of results:

- What defines retirement income adequacy?

- Should replacement rates be used? If they are used, what should be the target? Should target replacement rates differ across groups of people such as single persons, single-earner couples, or dual-earner couples?

- Should target replacement rates differ and be modeled by age of retirement?

- What should be the planning period for modeling, and how does that differ among the groups of people above?

- What probability of success is desired when using stochastic modeling?

- What rates of return should be used in deterministic models?

- What default rates should programs provide for inflation, investment returns, life expectancy, and income replacement?

- Why are there such different outcomes from program to program?

In sum, the 2009 authors concluded, as did the 2003 study authors, that any one retirement software “should not be used as the sole input for decision-making for retirees.”

The Takeaway

Software companies are not at fault for shortfalls in what planners need from their programs. The fault lies squarely with us—the financial planning industry—for assuming retirement income can be secured for all people through management of assets alone, even though it is a well-known fact that mid-market baby boomers currently have insufficient assets and self-insure multiple retirement risks.

The findings of both of these studies point to the need for the financial and retirement planning industries to take the lead in developing best-practice guidelines for the middle-mass and middle-affluent markets for software companies to build into their models. The 4 percent to 5 percent safe withdrawal rate, primarily an asset management approach to retirement income that works well for higher-net-worth clients, is clearly not enough for the mid-market. Key retirement risks such as longevity, inflation, health, and long-term care need to be addressed before asset allocation decisions are made, because the limited resources of the mid-market pre-retirees and retirees are required to do double duty. Optimization of assets for these market segments will require software that can model multiple approaches to help advisers decide which strategies potentially meet a client’s needs.

Once best practices for managing post-retirement risks and income are identified, modeling methods and client reporting will quickly improve. Creating an income floor based on essential and discretionary expenses, which also transfers as many longevity, inflation, and long-term care risks as possible, is best for the mid-market, while the 4 percent to 5 percent rule is most appropriate for higher-net-worth clients. However, more research on modeling methods is needed. It’s not the responsibility of software developers to identify the standards to include for meeting clients’ retirement income planning needs. It’s ours.

Endnotes

- Sondergeld, Eric T., et al. 2003. Retirement Planning Software. Schaumberg, IL: Society of Actuaries, LIMRA, and InFRE.

- Turner, John A., and Hazel A. Witte. 2009. Retirement Planning Software and Post-Retirement Risks. Society of Actuaries and the Actuarial Foundation. Software analyzed in this report included: (free consumer programs) Fidelity Retirement Income Planner, AARP Retirement Calculator, MetLife calculators, EBSA Taking the Mystery out of Retirement Planning, and the T. Rowe Price Retirement Income Calculator; (fee-based consumer program) ESPlanner; and (professional programs) NaviPlan Standard, NaviPlan Extended, EISI Profiles Professional, PIE’s MoneyGuidePro, AdviceAmerica—AdvisorVision Retirement Income Edition, and Money Tree.

- Abkemeier, Noel, and Brent Hamann. 2009. Segmenting the Middle Market: Retirement Risks and Solutions–Phase 1 Report. Schaumberg, IL: Society of Actuaries.