Journal of Financial Planning: August 2012

Executive Summary

- One of the biggest financial gaps in Americans’ portfolio of investment and protection holdings is protection against the financial consequences of becoming disabled and not being able to work for a considerable time.

- This is a prevalent risk, far more common than most people realize. The Social Security Administration estimates that one in four of today’s 20-year-olds will become disabled before they retire.1

- Importantly, there is strong evidence that many financial advisers are not expending enough effort to educate their clients on the risks of disability or putting a plan in place to mitigate their financial impact.

- These gaps are especially pronounced among women, who are more likely to become disabled, more receptive to planning, and more receptive to transferring risk to insurance.

Mathew Greenwald, Ph.D., established his research and consulting company, Mathew Greenwald & Associates Inc., in June 1985. He has done strategic planning and marketing research for over 100 of the most prominent financial services companies and numerous other organizations. Greenwald has a Ph.D. in sociology from Rutgers University.

Mary Quist-Newins, CFP®, CLU, ChFC, is an assistant professor and director of the State Farm Center for Women and Financial Services at The American College. Prior to joining The American College in 2008, she was a senior financial consultant and region management associate at Thrivent Financial for Lutherans. Quist-Newins holds an M.B.A. from the Garvin School of International Management and a B.A. from the University of Washington.

The State Farm Center for Women and Financial Services at The American College recently conducted a survey to gain insight into the awareness, concerns, and actions of women (and men) toward disability and the inability to work should a disabling condition occur. The results provide insights that can help financial planners refine their efforts on the issue of disability and hone the way they present information, analysis, and planning solutions. We hope the findings from this study will encourage financial planners to discuss the risk of disability with their working clients and help these clients develop a prudent plan to protect against what is often a devastating risk. Specifically, this paper will provide context relative to disability incidence, causes, important trends, and key findings from The American College research with implications for financial planners.

Context on Disability

For most working Americans, their ability to earn an income and their future stream of earnings is their most valuable asset, by far. This holds true even for those with relatively modest incomes. For instance, the present value of an asset based on an annual earnings stream of $50,000 for 40 years, and adjusted for 3 percent annual cost of living increases, is $1,155,738. Few Americans are in a financial position to replace hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars in the event of a disability. Yet, this is exactly what is at stake for many.

As acute as the risk of disability is for men in the United States, it is even greater for women. Women are more prone to disabling health conditions and less likely to have disability income insurance through their employer or via individual purchase. To gauge awareness of the risk of disability and the need for protection, especially among women, The State Farm Center for Women and Financial Services at The American College conducted a landmark study in partnership with Mathew Greenwald & Associates.

Disability Definitions, Rates, and Trends

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2005, 47.5 million adults (22 percent of all adults) reported a disability.2 The Census Bureau estimated that 15 percent of American adults (about 31 million) suffered a severe disability, while 7 percent (over 14 million) had a non-severe condition.3

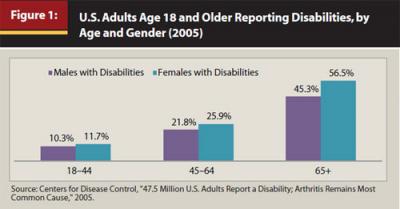

Clearly, as individuals age, the likelihood of suffering a chronic and disabling condition increases. As illustrated in Figure 1, women have a higher incidence of disability than men in all adult age groups. Further, because women live longer and have greater vulnerability to the risks of arthritis and autoimmune diseases than do men, their risks of becoming disabled grow more acute in their senior years.

For both genders, disability rates have been on the rise because of the aging and expanding girth of workers, as well as poor economic conditions and high unemployment. For example, applications for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) expanded from 2.3 million in 2008 to 2.8 million in 2009—a 21 percent increase.4 The incidence of disability for females has risen at a disproportionate rate relative to males, according to data from the Social Security Administration. Specifically, between 1999 and 2009, SSDI applications for men grew by 42 percent versus an increase of 72 percent for women.5

Causes of Disability

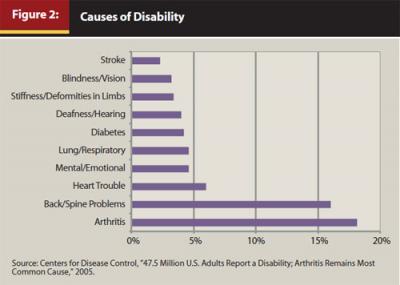

There are many misperceptions about health factors that lead to disabling conditions. Contrary to popular opinion, work-related accidents account for less than 5 percent of disabilities; the balance are caused by chronic illnesses.6 What are the leading causes of disability? According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the primary contributors are musculoskeletal disorders such as joint, neck, back, muscle, tendon, foot, ankle, and hand problems.

Many are surprised to learn that arthritis is the number one cause of disability among adult Americans. Figure 2, reflecting 2005 statistics from the CDC, provides useful perspective. How is this relevant to women? According to the National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research, females have higher rates of arthritis-related disability than males, even at younger ages. In fact, it is estimated that women are more than twice as likely to be disabled by arthritis as men.7

Research Findings

The high and growing incidence of disability and the fact that women are more likely to become disabled than men led The State Farm Center for Women and Financial Services at The American College to conduct a survey of consumer perspectives and understandings of this issue. In all, 1,600 working women and 800 working men ages 24 to 64 with minimum household income of $35,000 were surveyed online in November 2011. Respondents were drawn from Research Now’s deeply profiled, research-only online panel.8 The research firm of Mathew Greenwald & Associates implemented the survey. The research focused on: (1) understanding of the consequences of disability, (2) awareness of the risk of becoming disabled, (3) the steps that people have taken to protect against the potential financial consequences of becoming disabled, (4) current levels of knowledge of disability insurance, (5) perceptions of disability insurance coverage, and (6) attitudes toward disability insurance and reasons for buying or not buying. The findings provide important insights on how financial planners should approach clients about the risk of disability and how to deal with the potential financial consequences of becoming disabled.

Understanding of the Consequences of Disability

It is clear that most people have given little if any thought about what would happen financially to them and their family if they or their spouse became disabled and unable to work for at least three months. Indeed, just one in six says he or she has given this a lot of thought, while almost half have given it only some passing thought. But 1 in 10 has not thought about this subject at all. Thus, financial planners who raise this subject would not be addressing a topic that their clients have likely thought about in any meaningful detail.

It is of interest, but not surprising, that when it comes to the financial impact of disability, married people are just as likely to think about the impact of their spouse becoming disabled as they are about what would happen if they themselves get disabled. It is also of high interest that married women (19 percent) are more likely than married men (12 percent) to have given a great deal of thought to how they would manage financially if their spouse became disabled and unable to work for three months or longer.

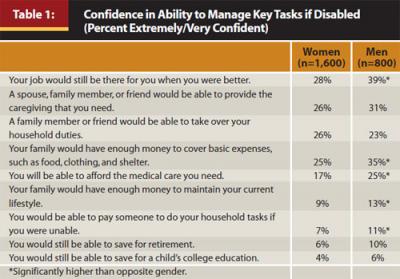

The survey respondents were asked how confident they are that they could afford to continue a variety of activities if they became disabled and could not work. There is a substantial lack of confidence, with women typically being more concerned and less confident than men. Even when it comes to having enough money for food, clothing, and shelter, 35 percent of women and 26 percent of men are not confident they would be able to afford these essential items.

In other financial areas, confidence about being able to cope with the financial consequences of being disabled is significantly lower. Forty-eight percent of women and 37 percent of men are not confident that they would be able to afford the medical care needed if they could not work due to disability. Majorities do not feel they would be able to afford to pay someone to perform the household tasks they do if they were to become disabled. Not surprisingly, 65 percent of women and 60 percent of men are not confident that they would be able to maintain their current lifestyle, and even higher proportions are not confident that they would be able to save for retirement if they became disabled. Therefore, there is recognition that a disability not only threatens the economic present but also the family’s future financial security. See Table 1.

Some people believe they could get help from family or friends if they became disabled, but many are less certain. About a third of men and women are not confident that they could get a family member or friend to help with household duties if they became disabled. A third of women but only a quarter of men say that they are not confident that a spouse, family member, or friend would be able to provide the caregiving they may need if they became disabled. The gap between males and females on this issue is intriguing. It seems clear that more men feel their wives would be able to help them if they became disabled than women feel they can count on their husbands. This is further evidence that the risk of disability is more threatening to women than to men.

When asked what financial resources they would use if they became disabled and not able to work for a year, only a third identify disability insurance. (Of course this percentage is substantially higher among those who own disability insurance.) Most assert they would use a wide variety of resources, including income from a spouse, retirement saving, Social Security disability payments, home equity, and money borrowed from friends and family. The largest proportion, 66 percent of women and 76 percent of men, cite cash reserves. But they also concede that cash reserves will not last long. Half (54 percent) state that their cash reserves will last five months or less.

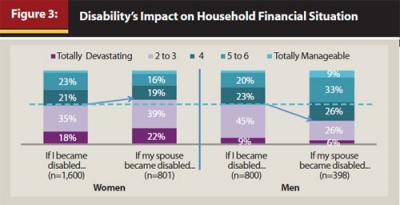

After having gone through the risks and consequences of disability, survey respondents were asked to rate, on a seven-point scale (in which one means totally devastating and seven means totally manageable), just how devastating they believe a disability would be if it happened to them. Fifty-three percent of women and 54 percent of men say the impact of disability on their family’s financial situation would be a “one,” “two,” or “three” (totally or close to totally devastating). See Figure 3.

This suggests that if a trusted financial adviser raised the issue of disability, it would not take much discussion for clients to realize how financially vulnerable they are if they do not have a well-developed risk management plan in place.

In sum, there is widespread and clearly justified belief among those who do not own disability income insurance that a disabling condition preventing a person from working even three months can have a very negative financial impact on a family, and that a disability that lasts a year can have a devastating impact. However, a key issue is how likely workers believe it is that they will become disabled during their working years. This issue was covered extensively in the survey.

Perceptions of the Risk of Becoming Disabled and Unable to Work

Most of the people surveyed have very little understanding of the potential risk of disability and believe their chances of becoming disabled are very low. For example, only 20 percent know that women are more likely to become disabled than men, and just 35 percent correctly estimate that a 20-year-old has about a one-in-four chance of becoming disabled prior to retirement.

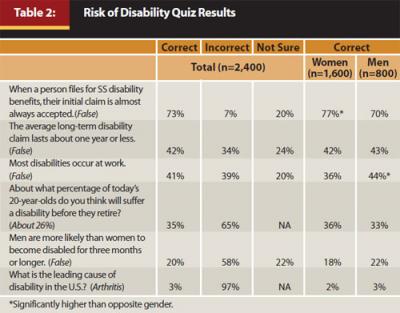

When taking a basic six-question quiz on disability risks, the overwhelming majority—86 percent—get three or fewer correct answers. Most striking is that 97 percent of respondents fail to identify arthritis as the leading cause of disability. If people knew the extent to which arthritis can affect the ability to work and knew how prevalent arthritis is, many would be more likely to want to develop a plan to protect themselves against the risk of being disabled. As perspective, Table 2 provides the quiz questions and responses.

Respondents were asked to rate the likelihood that, within the next decade, they themselves might become disabled and unable to work for at least one year. Half of women (51 percent) and 57 percent of men state that the chance of that happening to them is less than 5 percent. Perhaps this is why concern about becoming disabled is so low. Only 15 percent of both women and men are extremely or very concerned about becoming disabled and unable to work for a year, despite their widespread assessment that the financial impact of such a disability would be devastating. Further, over half of women (59 percent) and two-thirds of men (63 percent) are just not concerned about that possibility.

Steps Taken to Protect Against the Financial Risk of Disability

With their recognition of the financial consequences of disability, it might be assumed that people would take action to make sure they are financially protected, even if they feel the likelihood of becoming disabled is low. When faced with the possibility of financial devastation, it would be reasonable to research, develop, and put in place a risk management plan to protect one’s family. But that is not the case for most people. Only 5 percent of women and 8 percent of men have done “careful research” on how much disability insurance they need. While one-third of women (34 percent) and almost half of men (46 percent) have done some research, 61 percent of women and almost half of men (46 percent) have not done any research at all on this topic. This not only indicates an inability of consumers to address this issue, it also suggests that many financial advisers have not brought this topic up in any effective manner, if at all.

Problems with the Disability Insurance Coverage in Place

While half of respondents indicate they have disability income insurance through their employer, only a very small minority—6 percent of women and 8 percent of men—have purchased disability insurance individually. Of those with coverage through work, three-quarters of women (74 percent) have long-term disability insurance, 16 percent have short-term disability insurance only, and 10 percent are not sure what type of disability insurance coverage they have. For men, the proportions are quite similar.

There are several issues pertaining to the disability insurance that people have. First, there is evidence that many believe their existing coverage is insufficient. Half of those who are recipients of disability insurance (52 percent) believe the coverage is less than they really need. About that same proportion, 55 percent, who have a spouse with disability insurance believe their spouse’s coverage is not enough. For comparison, respondents with life insurance were asked whether their life insurance coverage was enough. Only 28 percent report their life insurance coverage is insufficient, far lower than for disability insurance. Thus, assessments of disability insurance coverage are quite different.

The research also found troubling knowledge gaps among those who have disability insurance. For example, about half of those with coverage do not feel knowledgeable about their policies. Forty-eight percent of female policy owners and 45 percent of male policy owners describe themselves as not too knowledgeable or not at all knowledgeable about the terms and coverage of their policy. More specifically, two-thirds of women (66 percent) and three-fifths of men (58 percent) do not know whether their disability income benefits would be taxed, and about half of women (51 percent) and men (48 percent) do not know how long their benefits will last once they start collecting them. Perhaps this lack of knowledge discourages people who feel their coverage is insufficient from getting more. It seems that a failure to carefully review the policy when it is bought or provided has led many not to obtain the additional coverage they feel they need.

Reasons for Not Buying Disability Insurance

There are several reasons, beyond the perception that the incidence of disability is low, why so many people do not buy disability insurance or increase their coverage to sufficient levels, but three stand out:

- The perception that this coverage is expensive. Given a list of seven potential reasons for not purchasing insurance, or purchasing additional coverage, the main rationale offered, by far, is that the coverage is too expensive.

- Financial advisers often do not bring up this issue. Only half of men who work with a financial adviser (52 percent) have spoken to their financial adviser about what would happen to them if they became disabled or seriously ill and could not work. Worse, only 37 percent of women who work with a financial adviser have talked to their adviser about what would happen to them if they became unable to work.

- Substantial lack of knowledge about disability coverage in general. This goes beyond the fact, previously addressed, that many people do not have sufficient knowledge of their own policies. Many people have serious gaps in their knowledge of disability insurance in general. Only 27 percent know that disability insurance benefits are usually taxed when they are paid out, and only 39 percent know that disability benefits are not adjusted for inflation. Only 40 percent know that disability insurance benefits make payments for a specified period, not as long as a person is disabled and unable to work.

Motivators for Purchasing Disability Insurance

One of the key questions in the survey concerns why those covered by disability insurance bought the coverage. Out of eight potential reasons posed to the respondents, the one selected most frequently as a major reason is “To make sure you and your family can stay in your home.” Seventy-five percent of women and 65 percent of men say that is a major reason. Coming in second is “For peace of mind,” a major reason for 68 percent of women and 55 percent of men. The third most selected reason is “To ensure you and your family could maintain your standard of living” (64 percent of women and 52 percent of men), and the fourth is “To pay for medical care or equipment you may need if you become disabled” (54 percent of women and 45 percent of men).

Two things are really important about this set of findings. First, the fact that the key reason for purchase is to ensure staying in the home shows the sensitivity of avoiding foreclosure. According to the Council for Disability Awareness, medical problems contributed to half of all home foreclosure filings in 20069 and 62 percent of bankruptcies in 2007.10 While the Great Recession may have skewed these statistics, homes are still expensive and it is hard for many to afford a down payment for the home they want, even if they are quite affluent. With foreclosure much in the news for the past few years, it is clear that many want the security of knowing that their mortgage will be paid, no matter what. As such, a minimal risk transference plan for those concerned about costs may be to cover mortgage expenses for at least a two- to three-year period.

The second important aspect of these findings is that each of these concerns is more important to women than to men. Throughout this survey, women express a greater concern than men about disability and a greater receptivity to coverage. Of course, it is significant that women are at higher risk of becoming disabled, but it is also significant that women are more receptive to risk transference through insurance. These findings further reinforce the importance of financial advisers educating female clients on the risks of disability and alternative approaches for their mitigation.

An Additional Issue

One additional and complex issue was raised in the survey. The respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “Even if a mother of young children is not working, it is important for her to have disability insurance because if she became disabled the family would need help managing her household tasks.” Thirty percent of women agree strongly with that statement and another 52 percent agree somewhat, for a total agreement of 82 percent. Interestingly, 24 percent of men agree strongly and 60 percent agree somewhat for a total agreement of 84 percent.

Providing disability insurance to women who are not employed outside the home is difficult because the risk of moral hazard can be high and insurable interest challenging to benchmark. But it is easy to understand the value of making sure children can be taken care of until age 3, and perhaps even age 6. The coverage may help to make sure children are properly supervised when very young and perhaps taken to and from school until they are able to do this on their own. For many, this type of coverage can be quite important. Indeed, it can make the difference between the ability to afford a high-quality day care facility (which can be expensive) and informal arrangements that can be unreliable and unfavorable to the young child. Of course, a great deal of care must be taken to properly design the policy and more due diligence is needed to ascertain whether or not insurable interest is sufficient to develop this coverage. That said, the survey findings suggest that some consideration should be given to this issue.

Implications for Financial Planners

One of the key findings of the survey is that relatively few people have spoken to a financial adviser about disability risks. Among those with an advisory relationship (approximately 30 percent for both genders), women were less likely than men to have spoken to their adviser about the possibility of being disabled and unable to work and the possibility of using insurance to deal with this financial risk. Just over a third (37 percent) of female respondents and half (52 percent) of males—a statistically significant difference—said they had this discussion.

It is not uncommon for women, and those who advise them, to undervalue the importance of their earning and financial power. Yet, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, in half of all dual-income households wives earned as much as their husbands in 2005 and in one in three households, females were the primary breadwinner.

Even for stay-at-home spouses, the replacement costs of services they provide can be far greater than one might imagine. For example, Salary.com, a market-leading compensation service, estimates that a full-time mother at home with two children, one in pre-school and one in grade school, contributes an annual economic value to her household ranging from $68,000 to $180,000 in 2009.11 Further exacerbating the infrequency of discussion about disability is that income insurance may be harder to underwrite and declinations/ratings are more common for women.

As a result of their greater disability risks, along with a lack of appreciating the value of a woman’s economic contribution to her family, it is especially striking that women with an advisory relationship are less likely than men to have had a discussion about disability with a financial adviser.

Whatever the reason, financial planners should not be dissuaded from talking about disability with their female prospects and clients beginning with awareness of the risk and plans they might have for its mitigation. Because two-thirds of male and female respondents in The American College survey had not calculated how much money they or their family would need each month if unable to work due to a disability, financial planners are presented with a clear mandate to help them do so. Beyond meeting monthly expenses, planners also need to assist clients in understanding the impact of a disabling illness or accident on the achievement of important financial goals, including retirement, education, and business continuation.

Determining how much financial risk the prospect or client is able to retain and how much might be transferred to insurance is best accomplished by developing a thorough understanding of current sources and uses of cash and how those might be changed by a disabling accident or illness. It is important to ascertain what lifestyle plans the client has to adjust in the event of a disability (for example, stay in home, move in with family). In addition, obtaining and analyzing employee benefits and group disability coverage are not only value-added but essential, as the College’s research findings indicate—just a minority of participants knew whether their plan was taxable and had inflation protection, and how occupational eligibility was defined.

Once client objectives, cash flow, net worth, and existing coverage information has been gathered, financial planners can analyze disability risk exposure. Whether the planner uses a goal-based or cash-flow driven planning platform, it is helpful to determine, in partnership with the client, which expenses might increase, decrease, or remain the same if a disabling event occurs. Discussing the impact of a disability by line-item expense serves to increase awareness of the risks involved, as well as the client’s engagement and support for the plan.

Because disability insurers usually limit income replacement to 60 percent–70 percent, it may not be possible to insure the full measure of anticipated needs. In addition, the client may not have sufficient means to afford the greatest transference of risk possible. As such, financial planners will want to show the results of the risk analysis, and, if they handle insurance in-house, present multiple product illustrations modifying waiting periods, benefit length, and riders. Providing education based on analysis findings, implementation alternatives, costs/benefits, and commissions enables informed decision making along with increased confidence and trust.

The bottom line is that many Americans, and especially women, do not realize just how prevalent the risk of disability is and how catastrophic the sudden cessation of their earnings could be. The underserved women’s market and the unaddressed risks of disability present financial planners with both opportunity and obligation. Women care about protecting themselves and their loved ones, and they want to know the risks they face. Many need both the education on their disability risks and a well-designed plan to address them.

Endnotes

- Social Security Administration, Fact Sheet, March 18, 2011.

- Brault, Matthew. 2008. Americans with Disabilities: 2005. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports (December).

- Ibid.

- Council for Disability Awareness. “Chances of Disability” statistics. www.disabilitycanhappen.org/chances_disability/disability_stats.asp.

- PRWeb.com. 2009. “More Women Turning to Social Security Benefits; Mothers Should Know Their Options” (May 5).

- Council for Disability Awareness. “The 2011 Council for Disability Awareness Long-Term Disability Claims Review. www.disabilitycanhappen.org/research/CDA_LTD_Claims_Survey_2011.asp.

- Jans, L., and S. Stoddard. 1999. Chartbook on Women and Disability in the United States. An InfoUse Report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research.

- The sample was drawn from the Research Now online panel, which is one of the largest online panels in the United States. The panel has three million members, and people join the panel by invitation only. The sample for this study is nationally representative of the United States population in the income and age segments selected for the survey. Invitations to participate in this survey were sent to a carefully constructed sample of panel members so the respondents were representative. After the responses came back, a weighting system was utilized, a common technique for surveys, to make sure that both the male and female samples conformed to the overall U.S. population on several key demographic criteria.

- Council for Disability Awareness ibid.; Robertson, Egelhof, and Hoke. 2008. “Get Sick, Get Out: The Medical Causes of Home Mortgage Foreclosures” (August 18). SSRN.com.

- Council for Disability Awareness ibid.; Himmelstein, Thorne, Warren, and Woolhandler. 2009. “Medical Bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: Results of a National Study.” The American Journal of Medicine.

- Salary.com, Mom Salary Wizard, July 18, 2009.