Journal of Financial Planning: August 2020

Bobby Henebry, CFA, is a partner at DM Capital and a globally recognized speaker on reinventing yourself in the digital age (www.BobbyHenebry.com).

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

Volatility is unnerving, and the current crisis has certainly put many advisers to the test as we work to do right by our investors, compound capital, and protect purchasing power in the face of maximum uncertainty. We are applying all of our past lessons-learned to a scenario we have never experienced before, and no one knows what will happen (interestingly, always the case). That said, times like these serve as a catalyst to check in, rebalance, and reallocate portfolios, so it is a good time to revisit the discussion on active versus passive, noting there is a broad spectrum of approaches that escape this simple bifurcation of investment ideologies.

Market dislocations can present tactical opportunities, but we will only know with the benefit of hindsight which moves pay off, and which don’t. There is also the question of when you apply hindsight, but I digress. When markets take investors for a ride, staying the course by doing nothing is often the wisest, and hardest, decision. Even though investors hire advisers to oversee their money, ultimately the investor is the chief investment officer, and in times of volatility, there is a strong urge to “do something.”

In addition to general anxiety around falling asset prices, pressure to make a move can also come from how much focus we place on index returns, which we often take to be “right” all the time. So we benchmark against them. We work to optimize returns around them (while minimizing costs). We may be hired and fired based on what we do relative to an index. Yet, investors generally pay us to find a solution that fits their unique circumstances. Even when a client’s portfolio allocation is intentionally totally different from the S&P 500, we may still be compared to it. But it is really difficult for investors to earn an index return over a very long period of time because human behavior is often a more powerful driver of ultimate performance.

Emotions Get in Our Way

Benjamin Graham’s classic manic-depressive character, Mr. Market, displays the irrational emotions that exist within all of us because Mr. Market wants to load up during a run-up and sell off in a downturn. We all know we are supposed to buy low and sell high, but our Mr. Market emotions drive us to do exactly the opposite. And that is why financial advisers are so valuable to our clients. Our value isn’t reflected in the comparison between client returns and “the market” or an index. An alternate return never seen (what I call a “personal benchmark”) would be dictated by Mr. Market emotions without sound advice from a thoughtful adviser.

Jack Bogle’s 2007 book, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing, builds a strong case for index investing, which is a great solution for many investors. He also identifies behavior as a huge factor in an investors’ ability to achieve low-cost index returns, because investors’ real returns are dollar-weighted.

In the book, Bogle points out in a study of fund returns, fund flows, and investor returns over a 25-year period, “the average fund investor earned, not the 10.0 percent reported by the average fund, but 7.3 percent—an annual return fully 2.7 percentage points per year less than that of the fund.” Note that over this same period, the index fund he was tracking provided an annual return of 12.3 percent, and the 10.0 percent is effectively a net-of-fee return. So 2.3 percent can be netted out due to fees, and another 2.7 percent was driven by investors moving money in and out at the wrong times. These numbers today are different, but the trend is clear—investors, as a group, do not achieve index returns because, in part, their emotions lead them to make the wrong moves at the wrong time.

Market Volatility Driving Interest in Active?

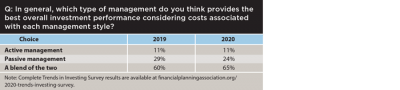

Let’s look at what advisers have been doing recently. FPA and the Journal conduct an annual Trends in Investing Survey, and the results for 2020 are out.1 One question asked advisers their opinion of active and passive investing (see the table above).

At a high level, there is a strong preference for blending active and passive approaches (the “gray zone”). Looking at the year-over-year change in the annual survey data, the main shift has been out of passive and into a blend portfolio, which I take to mean active increased on the margin. This shift is not surprising to me, because interest in active management is generally correlated with market volatility. A discerning investor can identify inefficiencies when a market dislocation occurs. Not every active manager will be successful at capitalizing on these opportunities, but some will.

The year-over-year numbers for active-only management are flat. I take that to mean there is a structural percentage of investors who simply always go active, but you may have a different interpretation of these figures.

No Silver Bullet

Jack Bogle is right that fees matter, and index funds do an excellent job of keeping costs down while providing broad market diversification. Thoughtful management also matters, and some active managers look at a pure index, which has all sorts of companies they would never want to own, and say any fee is too much for being obligated to own certain companies in an index. There are good arguments on both sides, but life is often not black and white; most of life exists in the gray zone. According to the 2020 Trends in Investing Survey, 65 percent of advisers agree that “a blend of the two” provides the best overall investment performance, because diversification matters—even across ideologies. There is no silver bullet for the markets.

As noted, there is a spectrum of approaches from pure passive to fully active, and everything between is the gray zone. On the pure passive end, you could use the MSCI AC World or S&P 500 for equities, pay the lowest fees, and “be the market.” Target Date funds are also a set-it-and-forget-it option for a hands-off investor who wants to pay very low fees. Or, you might diversify a bit (at a very low cost), use your own active overlay, and invest in a combination of Vanguard funds.

You might instead choose Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) and attempt to outperform an index over time through a disciplined, systematic approach to investing that owns a global universe of listed securities. And DFA works to stay true to their target allocations over time, while keeping costs as low as possible. Many investors would categorize all those options as “passive,” even though there are some active components, and these approaches are a very good fit for many investors.

We then move further out on the active spectrum to access a range of stock-pickers, venture, private equity, global macro, and the list goes on. Each approach has its day in the sun because different approaches outperform or underperform at different points in the market cycle and over different horizons. So diversification, even across ideologies, really counts.

Investment Management in Action

Joshua Jones, CFP®, is CEO of Everspire, a Utah-based RIA. Everspire leverages DFA funds for clients, and he observes, “Where markets are most efficient, we provide algorithm-driven allocations primarily through DFA. We are extremely active in markets that are less efficient, implementation of advanced tax strategies, and/or execution of a financial plan.”

An interesting hybrid approach has emerged from St. Louis-based RIA, Anderson Hoagland & Co., which had traditionally been a stock-picking firm. Then they subscribed to the observation that most of the outperformance opportunities come from allocation as opposed to individual security selection. So they began picking fewer stocks and adding larger allocations to index funds, especially those with a quantitate formulation that is implemented on an ongoing basis, to express the sector and style opportunities they favored.

Portfolio manager and partner, Craig Hoagland, explains, “We reached a tipping point after an extensive study of published research which demonstrated that the alpha of effective long-term active styles could largely be replicated through quantitative sort-and-buy strategies. For example, owning 500 value stocks selected based solely on valuation statistics through an ETF captured much of the outperformance of doing detailed work on 30 value stocks, with the added benefits of more diversification and less volatility.” The firm now combines a limited amount of active security selection with large allocations to index funds for their clients.

The term “active” is much broader than we may recognize. In addition to listed securities, “active” captures private real estate, venture investments, private equities, hedge funds, long-short, global macro, and many more strategies. All of these opportunities contribute to whatever “the markets” return, and the market does have a history of inefficient moments. As my partner at DM Capital, Dan Micit, says, “Markets are mostly efficient most of the time.” So he is willing to hold a concentrated basket of roughly 10 value stocks and wait patiently, as he has done for the past 14 years, for those infrequent disruptions that create opportunities to find real value.

Venture investment opportunities are growing in a number of emerging ecosystems around the country, from Tampa-based networks, Synapse Innovation Hub and Florida Funders, to Greenville, S.C.-based Venture South, which brings together more than 300 accredited angel investors to vet early-stage ventures and enable their investors to syndicate opportunities for those interested in each startup (sometimes in sizes as small as $5,000 to $10,000). They also have a venture index that allows investors to participate in all deals—an interesting active-passive hybrid option in venture.

Traditional private equity investments have burdensome minimums that prevent many investors from participating. But solutions like 10Talents Investors allows qualified purchasers to pool together and access private opportunities in much smaller sizes. They help some advisers bridge the gap to private investments.

These examples highlight the range of thoughtful approaches available to advisers and their clients. The world is more complex than the titles “active” and “passive,” and advisers appear to prefer allocations that combine both approaches.

What gets lost in this discussion is that time in the market is more important than timing the market. Whether you choose some flavor of active, passive, or a blended approach, it is sticking with it that has been a stronger determination of long-term returns. Otherwise, you become like Mr. Market, and those instincts don’t always lead to the best results, as Bogle’s research highlighted. It is also true that staying in can lead to losses, especially if you realize losses. There is certainly risk in investing, and we must make sure we address each clients’ capacity and willingness for risk. Disclosure and transparency are critically important for the integrity of our profession and the interests of our clients.

The discussion around what type of management will outperform will always take place, and that’s what makes the markets so wonderful. They represent a broad spectrum of choices for investors. And most advisers seem to diversify in a way that combines the best of active and passive philosophies, especially in times of maximum uncertainty.

This information has not been audited for accuracy, and is not intended as a recommendation to buy or sell any security, fund, or manager.

Endnote:

- The 2020 Trends in Investing Survey report, sponsored by Janus Henderson Investors, is available at financialplanningassociation.org/2020-trends-investing-survey.