Journal of Financial Planning: August 2021

Executive Summary

- The concept of Personal Financial Salience (PFS) can help explain the varying ranges of sensory responses individuals give regarding their personal financial situation. Sensory responses are operationalized by the level to which individuals allocate attentional, perceptual, and cognitive resources to their personal financial situation.

- Individuals who frequently use app-based and web-based financial planning products are allocating attentional resources to their financial situation; thus, financial planning product usage serves as a proxy to measure study participants’ PFS.

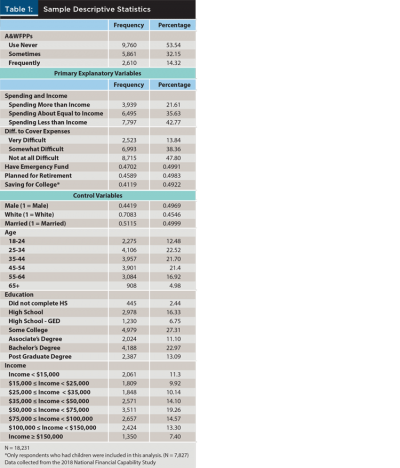

- Data collected from the 2018 National Financial Capability Study (N = 18,231) show that 2,610 (14.3 percent), 5,861 (32.15 percent), and 9,760 (53.54 percent) of participants frequently, sometimes, or never use financial planning products, respectively.

- The findings from multivariate analyses highlight that when compared to individuals who never use financial planning products, those who sometimes and those who frequently use financial planning products are more likely to find it easier to cover their bills, have an emergency fund, have a plan for their children’s college education, and have a plan for retirement.

- Financial planners can effectively utilize the concept of PFS in their practices. Creating an organizational hierarchy of financial task assignments and respective completion dates instills PFS. Furthermore, coordinating task assignments with salient reminders can further strengthen PFS and healthy financial behaviors.

Blain Pearson, Ph.D., CFP®, is a faculty member in the Department of Personal Financial Planning at Kansas State University, where he teaches courses in Behavioral Finance, Financial Counseling and Communication, and Capstone in Personal Financial Planning. Pearson’s primary research interests include the normative analysis of household financial decisions, financial behavior, and retiree well-being. Pearson holds his B.B.A and M.B.A from Campbell University, and his Ph.D. from Texas Tech University, is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™, and has multiple years of industry experience.

NOTE: Click on images below for PDF versions.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Introduction and Research Question

A key mechanism in determining one’s allocation of attentional resources to a specific task is the task’s salience (Bordalo, Gennaioli, and Shleifer 2013). An object or task’s salience determines how individuals focus their limited cognitive resources on relevant, or otherwise noticeable, sensory stimuli (Beckmann and Chow 2015). Saliency, from an evolutionary perspective, enabled survival by allowing attention deployment to protruding and situationally relevant stimuli, as in the case of threat avoidance (Wilson, Darling, and Sykes 2011) and foraging for food when hungry (New et al. 2007).

Today, the concept of saliency appears in a plethora of consumer behaviors. Chetty, Looney, and Kroft (2009) found that state-level increases in excise taxes that were tax-inclusive reduced aggregate alcohol demand significantly more than equivalent increases in sales taxes (added to the final price at the register). Wansink, Kent, and Hoch (1998) found that when grocery stores introduced purchase limits on discounted items, they increased the total quantity sold of the sale item.

This study examines if healthy financial behaviors are related to the saliency of one’s financial situation. If one’s financial objectives are cognitively prominent and enter one’s thoughts more frequently, the increased Personal Financial Salience (PFS) should elicit sensory responses that allocate attentional resources to the achievement of one’s financial objectives. The ultimate intent of this study is to provide evidence of the effectiveness of systems that reallocate attentional, perceptual, and cognitive resources toward healthy financial behavior.

Theoretical Background

According to the load theory of attention, individuals allocate attentional resources to process stimuli that evoke functional reactions (Lavie and Tsal 1994; Forster and Lavie 2007). Perceptual load refers to the perceived amount of attentional resources required in processing task-relevant stimuli, which is why perceptual load has been well-documented as a necessary condition for how individuals allocate their attention (Murphy and Greene 2016; Lavie 1995; Lavie and Tsal 1994). An example of perceptual load, as applied to auditory attention, is the cocktail party effect (Burwick 2014; Cherry 1953). The cocktail party effect is a phenomenon that explains the ability to focus auditory attention on a particular auditory stimulus, as when individuals select a conversation to focus on during a noisy cocktail party.

As the complexity of the task-relevant stimuli increases, more attentional resources are allocated to the task-relevant stimuli (Forster and Lavie 2007; Lavie 2005). Illustrator Martin Handford’s iconic “Where’s Waldo” children’s puzzles are examples of high perceptual load tasks, where the objective of the illustrations is to utilize attentional resources to locate the task-relevant stimulus (Waldo) amongst task-irrelevant stimuli (a sea of other characters and amusements). Task-irrelevant stimuli serve as distractors, and, in high perceptual load tasks, the depletion of attentional resources occurs quicker (Cartwright-Finch and Lavie 2007; Lavie et al. 2004). Attentional control theory suggests that performance inefficiencies occur when attentional resources are strained, as in high perceptual load tasks, leading to anxiety (Eysenck et al. 2007; Sadeh and Bredemeier 2011).

As Katsuki and Constantinidis (2014) note, individuals have limited capacity to process all sensory stimuli that are present, and the brain relies on many cognitive processes to allocate neural resources to task-relevant stimuli. Given the theoretical assumption that attentional resources have limited capacity (Lavie 2005; Katsuki and Constantinidis 2014), some researchers suggest attentional resources are allocated to the most salient task-relevant stimulus (Wolfe 1994). Krech and Crutchfield (1948) describe a salient stimulus as a stimulus that stands out as cognitively prominent and enters thoughts more frequently. Taylor and Fiske (1978) informally boil the definition down to “top of the head phenomena.”

The presence of a salient task-relevant stimulus helps explain how individuals react during high perceptual load tasks, ultimately providing for an understanding of how individuals’ attentional resources are drawn to qualities that are protruding and situationally pertinent. The concept of salience has been used to describe how individuals make consumption decisions (Berridge 2012), select role-identity (Thoits 2013), and interpret mortality (Burke, Martens, and Faucher 2010).

Applying the concept of Personal Financial Salience (PFS) may help explain the varying ranges of sensory responses individuals give regarding their personal financial situations. Sensory responses are operationalized by the level in which individuals allocate attentional, perceptual, and cognitive resources to their personal financial situation. Because saliency has been shown to be associated with planned actions (Parr and Friston 2019), increases in PFS may result in increases in the planned actions individuals take toward their financial objectives.

Personal Financial Salience, and App-Based and Web-Based Financial Planning Products

A newly emerging basket of salient stimuli is related to the human-smartphone relationship. Konok, Pogány, and Miklósi (2017) show that humans form attachment with their smartphones that are similar to social attachment, ultimately suggesting cultural recycling of the attachment system’s evolutionary structure. The increase in human-smartphone attachment has been associated with a host of negative byproducts, including increases in motor vehicle accidents (National Safety Council 2015), increases in guilt and pressure to respond to work-related tasks (Hall and Baym 2012), increases in anxiety in response to smartphone separation (Bragazzi and Del Puente 2014), and the emergence of cyberbullying (Hinduja and Patchin 2010; Kowalski et al. 2014). However, increased human-smartphone attachment has also brought a host of positive societal benefits, including greater interaction and collaboration in work and learning environments (Gikas and Grant 2013), more optimized communication (Geser 2004), and the development of applications to improve health (Fjeldsoe, Marshall, and Miller 2009; Khazaal et al. 2018).

In recent years, the emergence of app-based and web-based financial planning products has promised solutions to individuals who need financial guidance. Perceived value and product novelty have been essential in the mass adoption of these products (Karjaluoto et al. 2019; Li and Mao 2015). Many researchers have examined user responses in adopting and using app-based and web-based financial planning products (Lee et al. 2012; Peffers and Tuunanen 2005; Yen and Wu 2016).

The increase in human-smartphone attachment is theorized to be parallel with the increase in the use of and reliance on app-based and web-based financial planning products. More frequent use of app-based and web-based financial planning products may come in forms of increased screen time, push-notifications, and financial advice search. Individuals who frequently use app-based and web-based financial planning products have more attentional resources allocated to their financial situation, and this can serve as a proxy to measure individuals’ level of Personal Financial Salience (PFS). This study hypothesizes that increases in PFS, measured as the frequency of app-based and web-based financial planning product use, will lead to increases in the likelihood that individuals will have healthy financial behaviors.

Methods

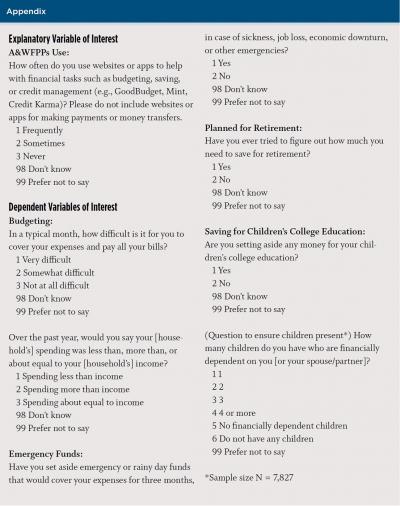

Cross-sectional data collected from the 2018 wave of the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS), a project of the FINRA Investor Education Foundation, were utilized to test the hypothesis. The hypothesis was examined by estimating regression models for healthy financial behavior dependent variables, based on the following NFCS questions (and answers): How difficult is it to cover your bills (“very difficult,” “somewhat difficult,” and “not at all difficult”)? Over the past year, would you say your spending was less than, more than, or about equal to your income (“spending less than income,” “spending more than income,” “spending about equal to income”)? Have you set aside emergency funds (“yes” or “no”)? Have you planned for retirement (“yes” or “no”)? Are you saving for your children’s college education (“yes” or “no”)? For the “Are you saving for your children’s college education?” question, the sample was limited to those with dependent children (N = 7,827). The complete list of questions is available in the Appendix.

The primary explanatory variable of interest comes from the NFCS question, “How often do you use websites or apps to help with financial tasks such as budgeting, saving, or credit management (e.g., GoodBudget, Mint, Credit Karma)? Please do not include websites or apps for making payments or money transfers.” Along with the sample’s descriptive statistics, Table 1 provides the frequency distribution of responses. The respondents (18,231) answered “Frequently” (2,610), “Sometimes” (5,861), and “Never” (9,760). “Don’t know” and “Prefer not to say responses” were dropped.

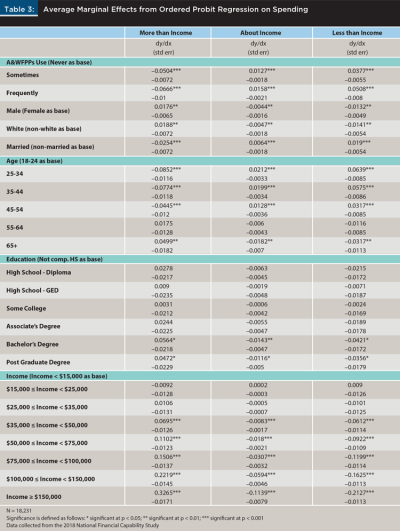

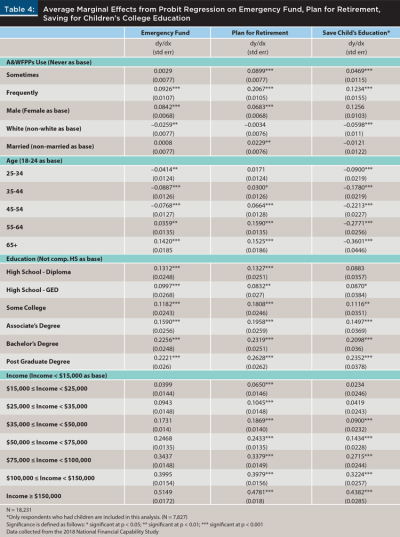

Ordered probit regression models were estimated for the difficulty in covering bills and spending dependent variables. Probit regression models were estimated for the emergency fund, plan for retirement, and saving for children’s college education dependent variables. The app-based and web-based financial planning product (A&WFPP) use variable entered all regression models as a categorical variable, with the “Never” category serving as the reference category.

Also included in the regression models were indicator variables for whether or not the respondent was male, white, and married, and categorical variables for age, education, and income. Prior research has shown that gender (Cueva and Rustichini 2015), race (Dettling et al. 2017), marital status (Garbinsky and Gladstone 2019), age (Bleijenberg et al. 2017), education (Fan and Chatterjee 2019), and income (Thornton and Tommaso 2020) are associated with healthy financial behaviors. Consequently, these variables were added as independent variables to the regression models. Survey weights were used to compensate for under and over representativeness in the sampling distribution.

Results

Tables 2, 3, and 4 provide the average marginal effects that are estimated from the regression models. The results are statistically and economically significant, and they provide evidence to support the hypothesis. Increases in the frequency of app-based and web-based financial planning product use is associated positively with all dependent variables tested. Thus, higher levels of Personal Financial Salience (PFS), measured by the usage of app-based and web-based financial planning products, are associated with increases in the likelihood that individuals will have healthy financial behavior.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that there is not a way to directly test the correlation between PFS and app-based and web-based financial planning products. To the author’s knowledge, a variable directly measuring PFS, or a well-researched latent measure, does not currently exist. Thus, usage of app-based and web-based financial planning products can only be theoretically motivated as a way to measure PFS.

An additional limitation to note is that the data do not provide a way to measure the study participants’ comfortability with computers and smartphones. If individuals are more trusting of computers and smartphones, they may also be more inclined to use app-based and web-based financial planning products. Additionally, individuals who frequently use app-based and web-based financial planning products may be more financially savvy, and thus are an inherently different group than those who do not use app-based and web-based financial planning products.

Discussion

This study examines the relationship between varying measures of healthy financial behaviors and Personal Financial Salience (PFS). The results indicated that increases in PFS, as measured by frequent use of app-based and web-based financial planning products, is associated positively with the practice of healthy financial behavior. When compared to individuals who never use app-based and web-based financial planning products, those who sometimes and those who frequently use these products are more likely to have an emergency fund, find it easier to cover their bills, save for their children’s college education, and have a plan for retirement. The findings support the notion that increasing individuals’ PFS increases the likelihood of achieving healthy financial behavior.

Load theory of attention dictates that individuals allocate attentional resources to process stimuli that evoke functional reactions (Lavie and Tsal 1994; Forster and Lavie 2007). The effective frequency and emotional impact of the financial stimuli act as an interruption system, reallocating individuals’ attentional, perceptual, and cognitive resources toward their personal financial situation. The resulting reactions serve as sensory responses to the abrupt financial stimuli introduced.

Massive increases in PFS may stimulate preoccupation with a restrictive number of short-term financial objectives. Thus, motivational relevance for a specific financial stimulant is a consideration for financial planners introducing financial stimuli. Moreover, the motivational relevance for a given financial stimulant is likely to continuously change during a client’s life course. For example, a younger client may have a goal of saving for the purchase of a home and a goal of saving for retirement. For the younger client, financial stimuli surrounding budgeting for the goal of a home purchase will be more motivationally relevant when compared to the goal of saving for retirement because of the differences in goal timeline. As a result, the potential risk with prompting increases in PFS based on motivational relevance is that motivational relevance may lead to the queueing of other client financial goals. The queueing of other financial goals can result in the postponement of neural resource allocation to the queued goals.

In addition, many financial objectives are nonunitary. The achievement of financial goals, generally, does not involve efforts concentrated on one task. Rather, the achievement of financial goals shares many tasks contained within an identity element. For example, the goal of retirement may involve setting up an individual retirement account (IRA). The goal of utilizing an IRA for retirement may involve many sub-goals, such as account establishment, creating a funding strategy, and selecting and managing investments. Thus, generic financial stimuli are likely ineffective in financial goal achievement.

Increasing PFS can responsibly be facilitated by creating an organizational hierarchy for financial task completion, and by creating a schedule of financial stimuli that prompts the periodic completion of financial tasks. Because the salience and priority of specific financial objective requirements, level of desire, and values are important for shaping client action (Cunningham and Brosch 2012), creating an organizational hierarchy for the completion of financial objectives provides a system for the organization of individual behavior and the needed completion of financial tasks. Furthermore, the periodic completion of financial tasks allows individuals to manage multiple financial tasks simultaneously. Thus, PFS is effectively utilized by creating an organizational hierarchy for the completion of financial tasks and scheduling distribution of financial stimuli in coordination with the financial tasks that require completion.

Conclusions

Personal Financial Salience (PFS) is a concept that describes how individuals allocate attentional, perceptual, and cognitive resources to their personal financial situation. The usage of app-based and web-based financial planning products is utilized as a proxy to illustrate how increases in PFS are associated with healthy financial behaviors.

The findings from multivariate analyses highlight that when compared to individuals who never use app-based and web-based financial planning products, those who sometimes use and frequently use these products are more likely to find it easier to cover their bills, have an emergency fund, have a plan for their children’s college education, and have a plan for retirement.

Financial planners can effectively utilize the concept of PFS by creating an organizational hierarchy for the completion of financial tasks. Creating an organizational hierarchy provides a system for the organization of clients’ financial task assignments. Assignment of financial stimuli in coordination with the organizational hierarchy is theorized to increase clients’ PFS, prompting clients’ allocation of neural resources toward the financial tasks that need completion.

References

Beckmann, Joshua S., and Jonathan J. Chow. 2015. “Isolating the incentive salience of reward-associated stimuli: value, choice, and persistence.” Learning & Memory 22 (2): 116–127.

Berridge, Kent C. 2012. “From prediction error to incentive salience: mesolimbic computation of reward motivation.” European Journal of Neuroscience 35 (7): 1124–1143.

Bleijenberg, Nienke, Alexander K. Smith, Sei J. Lee, Irena Stijacic Cenzer, John W. Boscardin, and Kenneth E. Covinsky. 2017. “Difficulty managing medications and finances in older adults: A 10-year cohort study.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 65 (7): 1455–1461.

Bordalo, Pedro, Nicola Gennaioli, and Andrei Shleifer. 2013. “Salience and consumer choice.” Journal of Political Economy 121 (5): 803–843.

Bragazzi, Nicola Luigi, and Giovanni Del Puente. 2014. “A proposal for including nomophobia in the new DSM-V.” Psychology Research and Behavior Management 7: 155.

Bordalo, Pedro, Nicola Gennaioli, and Andrei Shleifer. 2013. “Salience and consumer choice.” Journal of Political Economy 121 (5): 803–843.

Burke, Brian L., Andy Martens, and Erik H. Faucher. 2010. “Two decades of terror management theory: A meta-analysis of mortality salience research.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 14 (2): 155–195.

Burwick, Thomas. 2014. “The binding problem.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 5 (3): 305–315.

Cartwright-Finch, Ula, and Nilli Lavie. 2007. “The role of perceptual load in inattentional blindness.” Cognition 102 (3): 321–340.

Cherry, E. Colin. 1953. “Some experiments on the recognition of speech, with one and with two ears.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 25 (5): 975–979.

Chetty, Raj, Adam Looney, and Kory Kroft. 2009. “Salience and taxation: Theory and evidence.” American Economic Review 99 (4): 1145–77.

Cueva, Carlos, and Aldo Rustichini. 2015. “Is financial instability male-driven? Gender and cognitive skills in experimental asset markets.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 119: 330–344.

Cunningham, William A., and Tobias Brosch. 2012. “Motivational salience: Amygdala tuning from traits, needs, values, and goals.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 21 (1): 54–59.

Dettling, Lisa J., Joanne W. Hsu, Lindsay Jacobs, Kevin B. Moore, and Jeffrey Thompson. 2017. “Recent trends in wealth-holding by race and ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US).

Eysenck, Michael W., Nazanin Derakshan, Rita Santos, and Manuel G. Calvo. 2007. “Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory.” Emotion 7 (2): 336.

Fan, Lu, and Swarn Chatterjee. 2019. “Financial socialization, financial education, and student loan debt.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 40 (1): 74–85.

FINRA Investor Education Foundation. 2018. “The National Financial Capability Study.”

Fjeldsoe, Brianna S., Alison L. Marshall, and Yvette D. Miller. 2009. “Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36 (2): 165–173.

Forster, Sophie, and Nilli Lavie. 2007. “High perceptual load makes everybody equal.” Psychological Science 18 (5): 377–381.

Garbinsky, Emily N., and Joe J. Gladstone. 2019. “The Consumption Consequences of Couples Pooling Finances.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 29 (3): 353–369.

Geser, Hans. 2004. “Towards a sociological theory of the mobile phone.” In: Prof.Hans Geser: Online Publications. Zuerich, May 2004 (Release 3.0) http://geser.net/mobile/t_geser1.pdf

Gikas, Joanne, and Michael M. Grant. 2013. “Mobile computing devices in higher education: Student perspectives on learning with cellphones, smartphones & social media.” The Internet and Higher Education 19: 18–26.

Hall, Jeffrey A., and Nancy K. Baym. 2012. “Calling and texting (too much): Mobile maintenance expectations, (over) dependence, entrapment, and friendship satisfaction.” New Media & Society 14 (2): 316–331.

Hinduja, Sameer, and Justin W. Patchin. 2010. “Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide.” Archives of suicide research 14 (3): 206–221.

Karjaluoto, Heikki, Aijaz A. Shaikh, Hannu Saarijärvi, and Saila Saraniemi. 2019. “How perceived value drives the use of mobile financial services apps.” International Journal of Information Management 47: 252–261.

Katsuki, Fumi, and Christos Constantinidis. 2014. “Bottom-up and top-down attention: different processes and overlapping neural systems.” The Neuroscientist 20 (5): 509– 521.

Khazaal, Yasser, Jérôme Favrod, Anna Sort, François Borgeat, and Stéphane Bouchard. 2018. “Computers and games for mental health and well-being.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 9: 141.

Konok, Veronika, Ákos Pogány, and Ádám Miklósi. 2017. “Mobile attachment: Separation from the mobile phone induces physiological and behavioural stress and attentional bias to separation-related stimuli.” Computers in Human Behavior 71: 228–239.

Kowalski, Robin M., Gary W. Giumetti, Amber N. Schroeder, and Micah R. Lattanner. 2014. “Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth.” Psychological Bulletin 140 (4): 1073.

Krech, David, and Richard S. Crutchfield. 1948. Theory and problems of social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lavie, Nilli, and Yehoshua Tsal. 1994. “Perceptual load as a major determinant of the locus of selection in visual attention.” Perception & Psychophysics 56 (2): 183–197.

Lavie, Nilli. 1995. “Perceptual load as a necessary condition for selective attention.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 21 (3): 451.

Lavie, Nilli, Aleksandra Hirst, Jan W. De Fockert, and Essi Viding. 2004. “Load theory of selective attention and cognitive control.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 133 (3): 339.

Lavie, Nilli. 2005. “Distracted and confused?: Selective attention under load.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9 (2): 75–82.

Lee, Yong-Ki, Jong-Hyun Park, Namho Chung, and Alisha Blakeney. 2012. “A unified perspective on the factors influencing usage intention toward mobile financial services.” Journal of Business Research 65 (11): 1590–1599.

Li, Manning, and Jiye Mao. 2015. “Hedonic or utilitarian? Exploring the impact of communication style alignment on user’s perception of virtual health advisory services.” International Journal of Information Management 35 (2): 229–243.

Murphy, Gillian, and Ciara M. Greene. 2016. “Perceptual load affects eyewitness accuracy and susceptibility to leading questions.” Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1322.

National Safety Council. 2015. “Annual estimate of cell phone crashes 2013.”

New, Joshua, Max M. Krasnow, Danielle Truxaw, and Steven JC Gaulin. 2007. “Spatial adaptations for plant foraging: Women excel and calories count.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 274 (1626): 2679–2684.

Parr, Thomas, and Karl J. Friston. 2019. “Attention or salience?” Current Opinion in Psychology 29: 1–5.

Peffers, Ken, and Tuure Tuunanen. 2005. “Planning for IS applications: a practical, information theoretical method and case study in mobile financial services.” Information & Management 42 (3): 483–501.

Sadeh, Naomi, and Keith Bredemeier. 2011. “Individual differences at high perceptual load: The relation between trait anxiety and selective attention.” Cognition and Emotion 25 (4): 747–755.

Taylor, Shelley E., and Susan T. Fiske. 1978. “Salience, attention, and attribution: Top of the head phenomena.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 11: 249–288.

Thoits, Peggy, A. 2013. “Volunteer identity salience, role enactment, and well-being: Comparisons of three salience constructs.” Social Psychology Quarterly 76 (4): 373–398.

Thornton, John, and Caterina Di Tommaso. 2020. “The long-run relationship between finance and income inequality: Evidence from panel data.” Finance Research Letters 32: 101180.

Wansink, Brian, Robert J. Kent, and Stephen J. Hoch. 1998. “An anchoring and adjustment model of purchase quantity decisions.” Journal of Marketing Research 35 (1): 71–81.

Wilson, Stuart, Stephen Darling, and Jonathan Sykes. 2011. “Adaptive memory: Fitness relevant stimuli show a memory advantage in a game of pelmanism.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 18 (4): 781–786.

Wolfe, Jeremy M. 1994. “Guided search 2.0 a revised model of visual search.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 1 (2): 202–238.

Yen, Yung-Shen, and Feng-Shang Wu. 2016. “Predicting the adoption of mobile financial services: The impacts of perceived mobility and personal habit.” Computers in Human Behavior 65: 31–42.

Citation

Pearson, Blain. 2021. “The Role of Personal Financial Salience.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (8): 74–86.