Journal of Financial Planning: December 2012

Executive Summary

- Divorce and life insurance present issues in financial planning that are complex and often overlooked.

- Based on the current divorce rate and the current amount of life insurance in effect as of 2010, the financial planner will most likely encounter at least one client affected by divorce and life insurance proceeds.

- It is important for financial planners to be aware of their state law on divorce and life insurance proceeds. The reason is twofold: if the client is a beneficiary on a life insurance policy, to make sure the client gets the proceeds, and, if the client is the insured, to make sure the person the insured intends to get the proceeds does, in fact, get the proceeds.

- It is equally important to know what is meant by federal preemption and how it may affect the client’s receipt of life insurance proceeds or the distribution of the proceeds. It is not enough to know what the state law is, but whether or not that state law will be preempted by federal law.

- The authors discuss some of the state statutes and cases dealing with this issue, as well as federal preemption cases, to give financial planners an idea as to why this should be explored with clients.

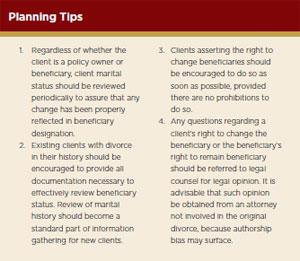

- The authors also provide planning tips for the financial planner.

- This paper is for informational purposes only. Financial planners should consult a licensed attorney for specific client cases because laws vary by state and other circumstances.

Suzanne M. Gradisher, J.D., is an assistant professor of business law at the University of Akron in Akron, Ohio. She is the director of the university’s CFP Board registered program and faculty adviser for the student chapter of the Financial Planning Association. She has been teaching since 2004 and has focused her research in accounting and tax issues, and most recently, in financial planning and law.

David R. Kennedy, Esq., has been a private practice attorney in Ohio since 1989. He concentrates his practice in the areas of probate and estate planning, general business, corporate, and real estate.

David Redle retired in 2011 after 31 years of teaching business law in the College of Business at the University of Akron. For 16 years prior to his retirement, he served as chair of the Department of Finance and helped develop and operate the CFP certification curriculum and student support services for the program.

Life insurance plays a major role in effective financial planning to assure that a surviving spouse and the families maintain acceptable standards of living after the premature death of the “breadwinner.” For most marriage relationships, the husband will be viewed as the breadwinner, though increasingly wives are fulfilling that role. In 2010, individual life insurance policies had a total value of $10.5 trillion. This market has grown at a rate of about 1 percent per year since 2000. And, the total coverage does not seem to be in jeopardy, because $2.9 trillion worth of new life coverage was acquired in 2010.1

Unfortunately, United States divorce rates are estimated at about 49 percent of all marriages.2 Consequently, about 50 percent of insurance policies intended to protect the surviving spouse and family are affected by divorce. On the surface, it would seem that resolution of life insurance issues upon divorce, given the pervasiveness of the issue, should be readily resolved. However, nothing could be further from the truth.

Recall that life insurance is a contract between the insurer and the owner. As part of the contractual relationship, the owner has the right to designate a beneficiary who will receive the benefits of the policy upon death of the insured party. Consider the plight of Bob and Mary. They have been married for years. However, the relationship deteriorates and ends in divorce. Given all of the anxiety, sometimes animosity, legal maneuvering, and resolution of potentially myriad property issues, one would think that the life insurance policy originally purchased to protect Mary, should Bob predecease her, would have been changed to reflect the change in circumstances. That may not be the case. For any number of reasons, the beneficiary of the policy may not have been changed. If Bob predeceases Mary, and if Mary remains as the named beneficiary on the insurance coverage, who is entitled to the proceeds of the policy? Should Mary receive it simply because she remains a named beneficiary? What is the likely intent of Bob, had he had the opportunity to consider the life insurance beneficiary? This could become particularly troubling if Bob had remarried. Would he not have wished to name his new spouse as beneficiary on the policy?

The issue of rightful claim to the proceeds of the life insurance policy after a divorce has arisen on numerous occasions. There is no uniform law among the states that resolves this matter. In addition, the preemption rights of federal law over state law may further complicate the issue. This paper explores how the law approaches the issue and presents strategies for the financial planner to provide the ultimate service to clients by taking steps to assure intentions are followed.

Beneficiary Designation: Directly, by Default, by Legal Mandate

The owner of a life insurance policy, unless restricted by some prior agreement, has power to change beneficiary. In most divorce situations, the owner of the policy changes the beneficiary, removing the former spouse and redirecting the proceeds to another beneficiary or beneficiaries. This is clearly the cleanest and most effective means of addressing a potential issue. As noted previously, such definitive action is not always taken. In circumstances where the beneficiary is not appropriately changed, the owner of the policy becomes subject to the law of the state of residence. To complicate matters, federal law may override state law provisions.

Direct Expression of Intent to Revoke. Traditional law requires that an overt act occur to change a beneficiary. This act could take the form of an actual change of beneficiary on an official beneficiary form or an acceptable legal document, such as a separation agreement as part of a divorce decree, evidencing intent to revoke the named beneficiary. In such jurisdictions, questions will usually turn on the interpretation of the separation agreement/property settlement that is part of all divorce decrees. For example, the property settlement between Carol East and her former husband, Dewey East Jr., came under review to determine whether it provided for revocation of Carol as beneficiary of an IRA.3 While this case addresses interpretation of the separation agreement, note that it involves an IRA. Most courts interpret beneficiaries of insurance contracts and IRAs in the same manner.4 Carol remained the named beneficiary on the initial documents establishing the account. A subsequent resubmission of account papers had no new information submitted in the beneficiary segment. The separation agreement did not specifically and clearly identify the subject IRA. Rather, Carol East argued that because it was not specifically identified, the separation agreement did not control the revocation of her as a beneficiary.

The estate of Dewey presented several arguments. First, it argued that Carol had waived her rights to the IRA proceeds in the separation agreement. Further, it argued that a subsequent account information sheet, which left the beneficiary designation blank, constituted a de facto change of the beneficiary to the estate. As noted, separation agreements and IRA accounts represent contracts between appropriate parties and are interpreted according to standard contract law. However, in interpreting the separation agreement, the court, while conceding that Carol may have waived spousal rights, found no evidence of her intent to waive her contractual right to the proceeds of the IRA. Therefore, the court concluded that her identification as a beneficiary in the initial creation of the account entitled her to proceeds.

As in other cases, this court clearly stated that a general division of personal property, even specific personal property, would likely not be enough to effectuate a waiver of the ex-spouse’s right to be the beneficiary of an IRA or life insurance contract. A beneficiary does not have personal property interests in the contract under examination. Rather, the courts have interpreted the rights of the beneficiary as “chose in action,” “inchoate rights,” or, in other words, incomplete rights in property.5 As such, general references to personal property rights or interest in separation agreements do not change the beneficiary status. This means that only specific language addressing the beneficiary status will operate to override a beneficiary who remained on the contract even after the divorce was completed. The case cites no fewer than six other jurisdictions that support its reasoning,6 and also cites the Utah case of Estate of Anello v. McQueen, 953 P. 2d 1143 (Utah 1998) as illustrative of where clear provision in the separation agreement controlled the revocation of beneficiary.

Patricia and Robert were married on May 14, 1966.7 In 1985, Patricia filed for divorce against Robert in the Supreme Court, County of Suffolk, New York. On March 31, 1985, the parties entered a stipulation settling the divorce action. On July 5, 1985, a judgment of divorce (JOD) was granted. Subsequent to his divorce, Robert McLean married Marilyn McLean. He named Marilyn as beneficiary on his life insurance policy. He died on September 3, 2009. Following his death, Marilyn filed a claim for the pension and life insurance benefits accorded to Robert. The insurer paid the life insurance proceeds to her. The pertinent section of the stipulation of settlement, as it relates to the insurance claims, reads as follows:

11. The defendant hereby agrees that he will maintain his $125,000.00 life insurance policy through his employment naming the following individuals as irrevocable beneficiaries: PATRICIA A. MCLEAN as to 25% interest; MICHAEL MCLEAN, as to 25% interest; ROBERT MCLEAN, as to 25% interest; with the remaining 25% interest to a designated beneficiary. However, if no individual is designated on the policy as to the remaining 25% interest, then said sum shall be divided equally between ROBERT MCLEAN and MICHAEL MCLEAN.

Patricia sought a declaration that 75 percent of the proceeds of life insurance go to her and the two children, each to receive 25 percent of the face amount of the policy of $125,000. She based this on the stipulation of settlement as they were named as irrevocable beneficiaries. The court ordered this and reasoned in part that a promise in a separation agreement to maintain an insurance policy designating a spouse as beneficiary vests in the spouse an equitable interest in the policy specified, and that spouse will prevail over a person in whose favor the decedent executed a gratuitous change of beneficiary.

Statutory Revocation. The contractual relationship between insurer and owner relative to a named beneficiary will not be disturbed. However, some state legislatures have enacted what is commonly referred to as a “re-designation statute,” which provides for an automatic revocation of the ex-spouse as beneficiary upon divorce. Prior to 1990, Ohio law followed accepted law, requiring an actual revocation of beneficiary or clear contractual requirement to revoke a beneficiary in a divorce. However, in 1990 the Ohio legislature passed legislation8 that protects a deceased former spouse from his or her failure to overtly change the beneficiary on a life insurance policy. Under most circumstances, the failure of an owner of a policy to change the beneficiary after a divorce and remove a former spouse will not result in proceeds being paid to one most likely not intended to receive them. Where then will the proceeds be paid? The latter part of the statute clearly states that the former spouse designation is “revoked,” thereby removing that beneficiary. Contractually, a secondary beneficiary would then be in line to receive the proceeds. Absent named beneficiaries, proceeds will be paid to the estate of the deceased.

One recent case in Ohio illustrates the application of this law.9 In that case, a life insurance policy purchased by Thomas Grzely named his then girlfriend Melissa Singer as the primary beneficiary and his brother as the secondary beneficiary. Subsequently, Melissa Singer and Thomas Grzely were married, but later divorced in 2007. The separation agreement identified the insurance policy and provided release of policy interests by Melissa. When Thomas died in 2009, Melissa sought to obtain the insurance proceeds as the primary beneficiary. Thomas’s brother objected, arguing that under both the separation agreement and the Ohio statute, Melissa had no rights to the insurance proceeds. Noting that the statute would operate to revoke Melissa as primary beneficiary, the court determined that the separation agreement clearly had “provided otherwise.” In short, the court found the separation agreement specifically and unequivocally extinguished Singer’s beneficiary status. There was no need to also rely on the statutorily created “fail-safe” provision, enacted to revoke a life insurance beneficiary designation by operation of law in cases where the policy owner failed to do so after divorce or dissolution and where the agreement may have been silent or ambiguous. Therefore, Melissa had no standing as the primary beneficiary. The court awarded the proceeds to Thomas’s brother, the named secondary beneficiary.

Section 9.301 of the Texas Family Code provides an illustration of language of another statute that accomplishes the same end. That law states:

(a) If a decree of divorce or annulment is rendered after an insured has designated the insured’s spouse as a beneficiary under a life insurance policy in force at the time of rendition, a provision in the policy in favor of the insured’s former spouse is not effective unless:

(1) the decree designates the

insured’s former spouse as the

beneficiary;

(2) the insured re-designates the

former spouse as the beneficiary

after rendition of the decree; or

(3) the former spouse is desig-

nated to receive the proceeds

in trust for, on behalf of, or for the

benefit of a child or a dependent

of either former spouse.

(b) If a designation is not effective under Subsection (a), the proceeds of the policy are payable to the named alternative beneficiary or, if there is not a named alternative beneficiary, to the estate of the insured.

Where legislatures such as Ohio and Texas have enacted such re-designation statutes, a judicial decree ending a marriage will serve to automatically revoke a former spouse as a designated beneficiary regardless of whether the policy owner actually performs such revocation. It is not an absolute, though, because prior agreements can preclude the operation of the law. Consequently, close attention to divorce-related documents, such as separation agreements and property settlements, remains appropriate. In most cases, those documents and the pertinent statute must be considered together.

Federal Preemption

Were it not enough of a problem to consider the law of the jurisdiction wherein the policy owner resides, together with interpretations of separation agreements and property settlements, the supremacy of federal law under certain circumstances further complicates the issues surrounding inadvertently retained beneficiaries after a divorce. Under the supremacy clause of the U.S. Constitution, and through numerous interpretations of the commerce clause of that constitution, federal law controls over state law when state law is in conflict with the provisions of federal law. This is the case in any life insurance policy or pension plan governed by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), 29 USCA 1001 et seq., as well as a multitude of other federal statutes.10 In case after case in which the source of death benefits is governed by ERISA, the courts have held that designation of beneficiary cannot be altered by agreement or state statute. In short, where ERISA applies to an employment benefit such as an employer-provided insurance policy, failure to overtly change the beneficiary subsequent to divorce will provide the benefits to the divorced spouse regardless of what divorce documents or state law provides. Three cases are illustrative.

Egelhoff v. Egelhoff involved a re-designation statute.11 Mr. Egelhoff designated his then wife as the beneficiary of a life insurance policy and pension plan provided by his employer and governed by ERISA. They later divorced, and shortly thereafter, Mr. Egelhoff died, not having changed his beneficiary. Mr. Egelhoff’s children by a previous marriage filed suit in Washington state court to recover the insurance proceeds and pension plan benefits. They relied on Washington’s re-designation statute that provides that the designation of a spouse as the beneficiary is revoked automatically upon divorce. The children argued that in the absence of a qualified named beneficiary, the proceeds would pass to them as Mr. Egelhoff’s next of kin under state law.

The trial court concluded that both the insurance policy and the pension plan should be administered in accordance with ERISA and granted the ex-wife summary judgment. Egelhoff’s children appealed. The Washington Court of Appeals reversed, concluding that the statute was not preempted by ERISA. The ex-spouse appealed. The state Supreme Court affirmed, holding that the statute is not preempted by ERISA. The ex-spouse appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In a 7-2 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the state statute has a connection with ERISA plans and is therefore expressly preempted. Justice Thomas reasoned that ERISA’s preemption section, 29 U.S.C. § 1144(a), states that ERISA “shall supersede any and all state laws insofar as they may now or hereafter relate to any employee benefit plan” covered by ERISA. A state law relates to an ERISA plan “if it has a connection with or reference to such a plan.” Accordingly, federal law preempted the Washington re-designation statute. The ex-wife won.

Similarly, the U.S. Supreme Court applied the supremacy clause in construing waiver language under state law when it came into conflict with the provisions of ERISA. In Kennedy v. Plan Administrator for DuPont Sav. And Investment Plan (2009) 555 US 285, William Kennedy designated his wife Liv as the sole beneficiary of his Dupont pension and retirement savings plans. The couple subsequently divorced, and as part of the settlement Liv waived any interests she may have had in the plans. However, William never submitted this portion of the settlement to the plan prior to his death in 2001, so the pension and retirement savings benefits were paid to Liv.

William’s estate brought suit against Dupont to recover the benefits. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas granted summary judgment for the estate, awarding it the value of the benefits. Liv appealed, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit reversed, explaining that because William had never submitted the portion of the settlement agreement denying the benefits to Liv, they were correctly paid to her by Dupont.

William’s estate appealed, and in a unanimous decision the U.S. Supreme Court held that Liv’s waiver of her former husband’s pension benefits upon their divorce was not rendered void by ERISA’s anti-alienation provision. However, the Court held that Liv was appropriately granted the benefits of her ex-husband’s pension because the plan administrator properly disregarded her waiver. It reasoned that the pension plan was clearly laid out and recognized Liv as the beneficiary. The plan had a mechanism in which Liv could have disclaimed her interest, but she did not. Also, William could have either submitted the settlement agreement to the plan administrator or changed the beneficiary. Since he did neither, Liv remained the proper beneficiary.

Also consider federal preemption trumping a state court divorce decree that specifically required the husband to keep the wife and children as the beneficiaries. In Ridgway v. Ridgway,12 Army Sergeant Ridgway divorced his first wife, April, in the state of Maine. At the time of the divorce, the sergeant’s life was insured under a $20,000 policy issued by the Office of Servicemembers’ Group Life Insurance (OSGLI), and April was the designated beneficiary. The divorce decree ordered Ridgway to keep the insurance policy on his life in force for the benefit of his three children.

Ridgway subsequently married Donna and changed the policy’s beneficiary designation to one directing that the proceeds be paid as specified “by law.” Under the OSGLI policy, this meant that the proceeds would be paid to the insured’s “widow,” in other words, his “lawful spouse … at the time of his death.”

Ridgway died, survived by Donna as his lawful wife. April instituted suit in state court against OSGLI, seeking to enjoin payment of the proceeds to Donna. Donna asserted that she was entitled to the proceeds based on the beneficiary designation and her status as Ridgway’s widow. April filed a cross-claim praying for the imposition of a constructive trust for the children’s benefit.

The trial court rejected April’s claims, taking the view that a constructive trust would interfere with the operation of the OSGLI, and thus would run afoul of the supremacy clause. April appealed, and the Maine Supreme Court reversed and remanded with directions to enter an order naming Donna as constructive trustee of the policy proceeds for the benefit of the Ridgway children. Donna then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In a 5–3 decision, the court held that OSGLI regulations preempt the domestic court order and the constructive trust imposed by the state court. Citing Wissner,13 the court determined that Congress had intended to “enhance the morale of the serviceman” and to “guarantee the complete and full performance of the contract to the exclusion of conflicting claims.” The Supreme Court further reasoned “the federal interest is especially strong because a substantial share of the proceeds of an OSGLI policy may be attributable to general tax revenues.” This is presumable because tax dollars are used to subsidize the premiums paid by servicemen and servicewomen and veterans.

It appears, then, that ERISA trumps any state re-designation statute or divorce decree whenever a contractually based employee benefit plan is involved. Obviously, benefits subject to ERISA must be carefully monitored and managed to assure that any and all beneficiary changes are effected in a timely and complete manner.

Is there any way around this preemption? One case suggests a possibility. However, the authors caution the reader to be very careful in relying on this case given its limited application and suspect legal reasoning.14 In 1986, Marilyn and Herbert Sweebe were divorced. Their judgment of divorce included a provision by which each agreed to give up any interest he or she had in any insurance contract or policy of the other. Herbert had a life insurance policy provided by his employer. In 1963, he’d designated his spouse Marilyn as the beneficiary. He never changed this designation after they divorced. When Herbert died in 2001, the insurance plan administrator paid the insurance policy proceeds to Marilyn because she was listed as the named beneficiary.

Herbert’s surviving spouse, Gail Sweebe, was appointed personal representative of his estate. She filed a motion to enforce the waiver in the judgment of divorce on behalf of the estate. The circuit court denied the motion because it held that ERISA preempted the waiver.

The Michigan Court of Appeals reversed the order of the trial court and remanded for entry of an order directing Marilyn to pay Herbert’s estate an amount equal to the insurance proceeds. The court of appeals held that Marilyn could not retain the life insurance proceeds because she had expressly waived any entitlement to the proceeds in the consent divorce judgment. Marilyn made an appeal to the Michigan Supreme Court, which was granted.

The Supreme Court recognized that under the ERISA preemption, Michigan law cannot control the determination of the proper beneficiary, and that ERISA requires a plan administrator to distribute the proceeds of an insurance policy to the named beneficiary. Thus, the Court recognized that Marilyn, in this case, was entitled to receive the insurance proceeds because the decedent designated her as the beneficiary. Marilyn’s waiver of her rights under the insurance contract did not change the plan administrator’s duty to distribute the proceeds to Marilyn.

The Court then stated that once she’d received the benefits, the only other issue in this case involved Michigan law concerning waiver—which does not implicate ERISA. Once a plan administrator pays benefits to the named beneficiary as is required by ERISA, the Court held that:

“This does not mean that the named beneficiary cannot waive her interest in retaining these proceeds. Once the proceeds are distributed, the consensual terms of a prior contractual agreement may prevent the named beneficiary from retaining those proceeds.”

Then the Court affirmed the Court of Appeals and ordered that Marilyn pay to Herbert’s estate an amount equal to the life insurance proceeds of the plan. The Michigan Supreme Court held that a former wife who had waived her right to life insurance proceeds could not retain those proceeds that had been delivered to her by the plan administrator of an employer-provided life insurance policy when the former husband had failed to change the name of the beneficiary prior to his death.

Is there a way around federal law preemption? It may be in the state of Michigan. However, as noted before, such judicial prestidigitation should be approached very carefully.

Conclusion

The naming of a beneficiary on a life insurance policy or other contractual benefit, such as an IRA, cannot be taken lightly by either party to a divorce. Under state law, the content of the property settlement/separation agreement embodied in the divorce decree can determine who the beneficiary may be. Certainly the owner of the policy has an interest in being able to voluntarily change the beneficiary or to manage how beneficiaries are established. In a similar fashion, one who stands to benefit from the insurance policy or other contractual benefit has a vested interest in assuring those interests are preserved and protected.

If the beneficiary can be changed and is not changed prior to death, some states protect the owner of the policy by creating a statutory presumption that the beneficiary would have been revoked by virtue of the divorce. Other states place the burden on the owner of the policy to change the beneficiary or suffer the consequences of proceeds being paid to an unintended beneficiary. In any event, all provisions and intentions of state law might well be preempted should the policy or other benefit be part of an employee benefit plan protected by ERISA. But unless specifically prohibited by court order, both state and federal law permit the owner of the policy to voluntarily change the beneficiary of the policy plan.

Endnotes

- American Council of Life Insurers. 2011. 2011 Life Insurers Fact Book. Chapter 7.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Marriage and Divorce Rate Trends. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/marriage_divorce_tables.htm.

- PaineWebber Incorporated et al. v. Carol S. East, No. 44, September Term, 2000.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Stolte v McLean 2012 NY Slip Op 50115(U) Decided on January 25, 2012 Supreme Court, Suffolk County Mayer, J. Published by New York State Law Reporting Bureau pursuant to Judiciary Law § 431. (This was a trial-level decision.)

- Ohio Revised Code §5815.33.

- Grzely v. Singer, Court of Appeals, Eleventh District, No. 2011-L-106 (2012).

- The federal preemption extends to other governmentally sponsored or issued benefits through laws such as: National Service Life Insurance Act of 1940 and 1958 (NSLI), 54 Stat 1010 et seq.; the Federal Employees Group Life Insurance Act of 1954 (FEGLIA), 5 USC 8701 et seq.; the Servicemen’s Group Life Insurance Act of 1965 (SGLIA), 38 USC 1965 et seq.; the Railroad Retirement Act of 1974 (RRA), 45 USC 231 et seq.; the Public Safety Officer’s Benefit Act of 1976 (PSOBA), 42 USC 46 et seq.

- 522 U.S. 141 (2001).

- Ridgway v. Ridgway, 454 U.S. 46 (1981).

- Wissner v. Wissner, 338 U.S. 655 (1950).

- Sweebe v. Sweebe, 474 Mich. 151, 712 N.W. 2d 708 (2006).