Journal of Financial Planning: January 2013

What is financial planning? Financial planning can be defined as a profession that helps people make good decisions. I presented this definition in the FPA-published article, “Lack of Clarity Holds The Profession Back” (see the July/August 2012 issue of Practice Management Solutions at www.FPAPracticeManagement.org), and on FPA Connect (connect.FPAnet.org), but my definition lacked a critical element—a process for actually helping people make good decisions.

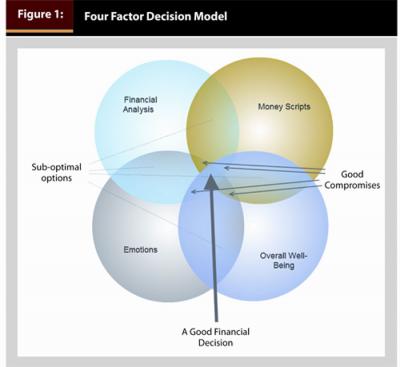

Making financial decisions can be broken down to the interplay of four factors. Conventional six-step financial planning focuses heavily on one of these factors. Literature in the life planning movement tackles another, and behavioral finance a third. To my knowledge, the fourth factor has been only tangentially touched upon in the financial planning literature.

Factor 1: Financial Analysis

The financial planning profession is strongly grounded in financial analysis. For many financial planners, financial analysis remains the core service they offer clients. The CFP six-step process is designed to offer deep financial analysis to help make decisions.

Unfortunately, financial analysis has been viewed for too long as the overriding, predominant factor in making good decisions. We have boiled every decision down to a cost/benefit analysis without giving proper consideration to other factors that weigh heavily in our clients’ decision-making processes.

Financial planners can offer dozens of stories about clients who would not follow solid, well-grounded advice based on financial analysis. This story has several archetypes: the client who continues spending right into oblivion, the client who refuses to prepare an estate plan or even name a guardian for their children, and so on.

Financial analysis alone does not help people make good decisions. It represents only one factor, and relying on it too heavily can lead to indecision or poor decisions. Financial analysis can illustrate how to improve one’s financial well-being, but it does not capture everything necessary to make a good financial decision.

Factor 2: Money Scripts/Experiential Learning

George Kinder and Dick Wagner delivered a first look into the second factor involved in financial decision making by suggesting that helping clients had to involve more than financial analysis. Life planning brought clients’ values and beliefs into financial decision making.

Brad Klontz, Rick Kahler, and Kathleen Fox furthered our knowledge with the notion of money scripts. Not only were we beginning to include clients’ beliefs and values into financial decision making, but we learned that clients were operating under assumptions and ideas about money that needed to be understood.

These money scripts affect every decision a person makes, both in positive and negative ways. A script as simple as “a penny saved is a penny earned” can profoundly impact how a person makes financial decisions. Someone who internalizes that message may strongly identify with financial analysis that shows the result of saving money early and often. Contrast that to a person who internalized the script “the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil.” Showing this person how saving early can result in tremendous wealth may, in fact, have the opposite effect desired.

Money scripts should be considered in our financial decision-making model, but they cannot be allowed to live unchecked. The “a penny saved is a penny earned” individual can become unwilling to use any of that money to live the life they want. Other decision-making factors are needed to balance financial analysis and money scripts to help these individuals make good financial decisions.

Factor 3: Emotions

Over the past several years, financial planning has become aware of the work on behavioral finance by Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Richard Thaler, Dan Ariely, and others. Behavioral finance recognizes that humans do not act rationally in all economic decisions, and that many factors can influence decision making.

Financial analysis may highlight an optimal economic decision, yet a variety of factors may lead a person to make a different decision. Behavioral finance shook up one of the most basic premises that traditional financial planning was built upon: people act rationally (in an economic sense) and people act in their best interests. In fact, people often do not act rationally and sometimes act contrary to their best interests. Emotions loom large in this work.

Emotions form the third factor in the four factor decision model. It is incumbent upon financial planners to recognize the impact emotions have on decision making and to help clients understand that impact. This factor requires that financial planners acknowledge the importance of client emotions, then help clients short-circuit the negative results those emotions are creating.

Financial planners shouldn’t discount emotions as invalid and try to get a client to move past them, however. The emotions a client experiences represent something important, something that needs to be accounted and planned for. As financial planners, we must help our clients make good financial decisions by placing their emotions in the proper context as part of the four factor decision model.

Factor 4: Overall Well-Being

The fourth factor that must be considered when making financial decisions is the impact of the decision on overall well-being. This factor is the most controversial, most nebulous, and most important.

Overall well-being must first be defined and differentiated from financial well-being. Gallup Inc. (the producers of the Gallup polls) and Healthways Inc. (a global well-being company) have formed the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index® to define and study overall well-being. The index reviews six domains as underlying overall well-being: life evaluation, emotional health, physical health, healthy behavior, work environment, and basic access (see www.well-beingindex.com for details).

A decision that only improves financial well-being but harms overall well-being has a likelihood of having a net negative impact on a person’s life. This cannot be considered a good financial decision.

As financial planners, we must be willing to help our clients recognize this. We must be willing to help them take a step back from the financial analysis to consider the impact a decision may have on their entire lifestyle. Sometimes we must even be willing to help them consider options that may be financially sub-optimal when those decisions best support overall well-being.

But again, overall well-being represents only one of the four factors in the decision model. It cannot be weighed too heavily. As with each of the three other factors, overall well-being has to be considered in the context of all four factors, not on its own.

Using the Four Factor Model in Financial Planning

The four factor model offers financial planners a comprehensive approach to help people make good financial decisions. Using the model, however, remains an art as much as a science. Using the model requires walking a client through the four factors and helping him or her determine which option best accommodates all four factors.

Using a simple, four quadrant work-sheet—where each quadrant represents one of the four factors—can help. Working together, the planner and client fill in each quadrant. The planner may refer to analysis prepared in the financial planning process to address the financial analysis quadrant. The client and planner work together to identify money scripts influencing the client, while the client completes the emotions quadrant (with insight from the planner.) The overall well-being quadrant would require a brief analysis of the six domains identified in the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index and the potential impact of various choices on each of these domains.

Having completed the four quadrant worksheet, the planner can guide the client through making a well-considered financial decision. Figure 1 illustrates what the decision process looks like.

The area being overlapped by all factors represents the options available that best address all four factors.

This process may be too intensive for every decision a client makes. However, early in the client-planner relationship, and when encountering high-impact decisions, using this process will help the client make a good financial decision. As the relationship evolves, some of this process may become internalized, allowing the planner and client to work through the process with a conversation.

The Future of the Profession

Ultimately, everything we do as financial planners comes down to helping clients walk through decisions they are making. How much should we or can we save? Can we retire today? Should we buy that car? How do we invest our money? Do we need insurance? As financial planners, we offer analysis and insight, but we do not make any of these decisions. We help people make good financial decisions.

To move the profession forward, it’s time we recognize that this is our purpose. And we need to have a more complete decision-making model than in the past. Relying on a financial plan and financial analysis alone does not consistently result in good financial decisions.

Nathan Gehring, CFP®, is an associate planner at KeatsConnelly, the largest cross-border wealth management firm in North America. Follow him on Twitter @nathangehring and on his blog, where he explores financial decision making at www.nathangehring.com.