Journal of Financial Planning: January 2015

William Reichenstein, Ph.D., CFA, holds the Pat and Thomas R. Powers Chair in Investment Management at Baylor University and is a principal of Social Security Solutions Inc. Email author HERE.

William Meyer is the developer of SSanalyzer.com, a software for advisers to evaluate and create Social Security claiming strategies. Email author HERE.

Executive Summary

- Nearly all financial planners know their clients’ Social Security benefits can be affected by earnings tests, but they seldom know the details of these tests. This paper is designed to provide background information about this important topic.

- This paper explains the details of a special monthly earnings test that sometimes applies in the first year a beneficiary is both entitled to a benefit and earns less than the monthly limit in at least one month.

- Several examples of earnings tests are provided to show how claiming strategies can influence the value of Social Security lifetime benefits. With this information, financial planners can help their clients navigate the limitations imposed by the earnings tests.

According to a study sponsored by Merrill Lynch (2014) in partnership with Age Wave, 72 percent of pre-retirees age 50 and older say they want to keep working after they retire. Most financial planners know that Social Security benefits can be affected by the annual earnings test, but they seldom know the details of this test. It is important for financial planners to have this detailed information to help their clients make the most of their Social Security benefits.

Earnings tests only apply if the person on whose earnings the benefits are paid is younger than full retirement age (FRA). For example, if Joe attains FRA, then his earnings would not affect his retirement benefits. Furthermore, his earnings would not affect his wife’s spousal benefits, which are based on Joe’s earnings record, even if she is younger than her FRA.

The annual earnings test has one of two possible earnings limits. The first applies to beneficiaries who will not attain their FRA by year’s end. In 2015, those falling into this category will have $1 of benefits withheld for every $2 of earnings above $15,720.

For example, in the absence of the earnings test, suppose John would be entitled to $1,500 per month in retirement benefits in 2015. He will not attain his FRA this year. He informs the Social Security Administration (SSA) that he expects to earn $30,000 in 2015. Because his earnings estimate is $14,280 above the earnings limit, he will have $7,140 withheld. To be specific, he will have all benefits withheld for five months, ($7,140/$1,500 and then rounded up to an integer). That is, he will receive no benefits in January through May. He will receive $1,500 per month from June through December. If his actual earnings turn out to be $30,000, as expected, then next year he will receive the $360 withheld in May that exceeded the $7,140 target withholding amount ([$1,500 per month x 5 months] – $7,140).

The second earnings limit applies to workers who attain their FRA that year. In 2015, such workers can earn $41,880 from January 1 through the end of the month before they attain FRA. They will have $1 of benefits withheld for every $3 of earnings over $41,880.

For example, suppose Peggy attains FRA in June 2015.1 In the absence of the earnings test, she would be eligible for $2,000 of retirement benefits per month. She informs the SSA that from January through May 2015 she expects to earn $50,000. Because her expected earnings are $8,120 above the earnings limit, she will have $2,707 withheld after rounding up to a whole dollar. To be specific, she will have all benefits withheld for two months ($2,707/$2,000 and then rounded up), so she will receive no benefits in January and February, but she will receive $2,000 per month from March through December. If her actual earnings from January through May turn out to be $50,000, as expected, then next year she will receive the $1,293 withheld in February that exceeded the $2,707 target withholding amount ([$,2000 per month x 2 months] – $2,707). Beginning in June, the earnings test does not apply. So, she could earn $100,000 from June through December with no effect on her benefits.2

Beneficiaries who anticipate their earnings will exceed the 2015 annual limit should report their estimated earnings to the SSA by the latter of December 2014 or their initial claims interview. Furthermore, the beneficiaries should notify the SSA any time work activity changes and at the end of the year if actual earnings are different than estimated earnings. If the SSA does not receive earnings information, it will use the amount reported by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for that year.

Earnings estimates can be reported to the SSA by telephone (800-772-1213) or in writing to the local SSA office. Written correspondence can be via a letter or by completing a mid-year mailer form. This form is provided to beneficiaries who have previously provided an earnings estimate to ensure their original estimates are still accurate. If the amount withheld in 2015 exceeds the amount that should have been withheld, the excess will be refunded to the beneficiary typically a few weeks after the annual report of earnings is filed, which can be as soon as actual earnings for 2015 are known. If the annual report of earnings is not filed, then excess withholdings for 2015 would likely be received about October 2016 after earnings are reported to the SSA by the IRS and the actual earnings have been posted to the individual’s earnings record. If not enough was withheld, an overpayment is posted to the worker’s record. This amount will be withheld from the beneficiary’s benefits at that time.

What Income Counts in the Annual Earnings Test?

Earnings for the annual earnings test consist of: (1) gross wages for services rendered in a taxable year plus (2) all net earnings from self-employment for that taxable year minus (3) any net loss from self-employment for that taxable year.

For the earnings limits, the SSA does not count: (1) other government benefits; (2) distributions from tax-deferred accounts, such as 401(k) or tax-exempt accounts including Roth IRAs; (3) investment earnings including interest, dividends, and capital gains; (4) pension benefits including Social Security benefits; and (5) payments from an annuity.

Furthermore, earnings count for the period earned and not when received. Therefore, payments that include accumulated vacation or sick pay, bonuses, severance pay, or deferred compensation will count for when they were actually earned, even if received after retirement and entitlement to Social Security benefits.

For example, suppose Sam retires from ABC Corp. in December 2015. In January 2016, he receives a year-end bonus for 2015 of $20,000. This income should not be included in his 2016 earnings because it represents payment made “after termination of employment relationship because of retirement.” However, the SSA has no way of knowing that this payment should not be counted unless Sam tells them. Therefore, if this $20,000 puts his 2016 earnings over the limit, then Sam should inform the SSA that this amount should not be counted.

Monthly Earnings Test

A special monthly earnings test sometimes applies in the first year a beneficiary is both entitled to a benefit and earns less than the monthly limit in at least one month. Ignoring for now a special rule that affects the monthly earnings tests for self-employed individuals, the monthly earnings limits are $1,310 if the beneficiary is under FRA at year-end 2015 and $3,490 if the beneficiary attains FRA during the year. These limits are equivalent to one-twelfth of the annual limits.

If earnings for the year are less than the annual exempt amount, it makes no difference if the money was earned in one day or spread out through the year. A beneficiary can use a monthly earnings test if he or she is entitled to a grace year and the monthly earnings test works to his or her advantage. A grace year is the first year a beneficiary is both entitled to a benefit and earns less than the monthly limit in at least one month.

The following three examples should help clarify this monthly earnings test.

Example: Suppose a 64-year-old worker earns $100,000 by June 30, 2015 and retires that day and begins her Social Security retirement benefits. As long as she earns $1,310 or less in each month from July through December,

her benefits in those months will not be affected. If she earns $1,311 or more in any month, then she will not be eligible for a benefit that month. In such months, the SSA will revisit her situation and use the annual test or monthly test, whichever is more favorable to her.

Example: Alternatively, suppose a 64-year-old worker earns $3,000 per month in January and February at which time he retires. He returns to part-time work and earns $2,000 per month from September through December. Because his annual earnings of $14,000 is less than the annual earnings limit, the annual earnings test would apply because it is more beneficial to him; he would not lose any benefits that year despite earning more than $1,310 in four months. In subsequent years, the annual earnings test will apply because he would no longer be in a grace year.

Example: Assume a child beneficiary’s benefits terminated in June because he graduated from high school. He earns $2,000 a month from June through December. Benefits paid in January through May would not be affected by his June-through-December earnings. As long as he earned $1,310 or less in each month from January through May, his Social Security benefits would not be affected. If he earned $2,000 in May, then he would not be eligible for a benefit that month unless his total earnings for the year were less than the annual limit. In such months, the SSA will revisit his situation and use the annual test or monthly test, whichever is more favorable to him.

The monthly earnings test applies in any grace year; that is, any year that meets the following conditions: (1) the beneficiary becomes entitled to a different type of benefit (retirement, spousal, child’s, widow’s, etc.); (2) a taxable year of entitlement to a different type of benefit that includes a non-service month, where a non-service month is a break in entitlement of at least one month; and (3) the beneficiary earns less than the monthly earnings limit.

Example: Suppose Sue was entitled to mother’s benefits (technically, spousal benefits) in 2012 because she was the caregiver to a child at home. Her initial grace year was 2012. In April 2015, her child reached age 16, so her mother’s benefit stopped; that is, April 2015 is a non-service month (NSM). In June 2015, she becomes entitled to retirement benefits based on her own earnings record. In addition, she earns less than the monthly earnings limit. Because she met all three conditions, she is entitled to another grace year in 2015, and thus the monthly earnings test applies to Sue for that year.

Exception: The same rules apply for the monthly earnings tests and the annual earnings test with the following exception. For the monthly earnings tests, additional limitations apply to self-employed beneficiaries and those beneficiaries who are in a position to control what is reported as earnings. Beneficiaries can receive benefits for months they are not performing “substantial services in self-employment.” Substantial services in self-employment is defined as occurring when a beneficiary devotes more than 45 hours a month to a business or between 15 and 45 hours to a business in a highly skilled occupation. In determining whether a person rendered substantial services in self-employment, each month is considered separately.3

For example, suppose John retires at age 62 on June 30, 2015. He earns $37,000 in 2015 before he retires. On October 5, John starts his own business. He works at least 45 hours a month for each month from October through December, and earns $1,000 each month after expenses. His total earnings for 2015 are $40,000. John will receive a Social Security payment for July, August, and September because he was not self-employed and his earnings in those three months were $1,310 or less per month (the limit for people who are under full retirement age). John will not receive benefits for October, November, or December 2015, because he worked in his business more than 45 hours per month in all three months.

Whose Benefits are Impacted?

Suppose Mathew, his wife, Mollie, and their daughter, Lisa, each receive monthly Social Security benefits based on Mathew’s earnings record. Mathew receives $866 per month, while Mollie receives $375 in spousal benefits, and Lisa receives $500. Based on this information, consider the following four examples:

Example 1: Mathew is at least FRA. Thus, his earnings would not affect his retirement benefits, Mollie’s spousal benefits, or Lisa’s child benefit.

Example 2: Mathew is younger than FRA and will remain younger than FRA for the entire year. Mathew earns $23,100 in 2015, while Mollie and Lisa have no earnings. The formula calls for SSA to withhold $3,690 in benefits, ([$23,100 – $15,720]/2). But since $3,690/$1,741 in combined monthly benefits based on Mathew’s earnings record rounds up to 3, SSA will withhold all benefits for three months. Mathew, Mollie, and Lisa will receive no benefits for January through March, but will receive their scheduled benefits for April through December 2015. In 2016, they will get a refund for the excess withholdings of $1,533 in March, ([$1,741 x 3 months] – $3,690).

Example 3: Mathew and Mollie are both under FRA for the full year. Mathew earns $23,100, while Mollie earns $17,200 in 2015. Mathew, Mollie, and Lisa receive monthly benefits of $866, $395, and $500 with Mollie’s benefits consisting of $320 of retirement benefits plus $75 of spousal benefits. Mathew’s earnings would cause Mathew and Lisa to lose their full benefit checks and Mollie to lose her spousal benefits for January through March ($3,690 / [$866 + $75 + $500] then rounded up). In addition, Mollie’s earnings would cause her to lose her retirement benefits for three months. In particular, the annual earnings test would force the SSA to withhold $740 of her benefits ([$17,200 – $15,720]/2). Because $740/$320 rounds up to 3, Mollie would have her retirement benefits withheld for three months. Mathew’s, Mollie’s, and Lisa’s benefits would resume in April.

Example 4: Assume Mathew is at least FRA, while Mollie is younger than FRA for the full year. Mathew earns $23,100 in 2015, while Mollie earns $17,200. Mollie receives $395 in monthly benefits, of which $320 is retirement benefits and $75 is spousal benefits. Because Mathew is at least FRA, his earnings test would not affect any of the benefits based on his earnings record. However, Mollie’s earnings would reduce both her retirement and spousal benefits. She would lose all benefits for two months ($740/$395 then rounded up). She would receive her $395 payment for March through December. In 2016, she will receive a refund for the excess withholdings of $50 in February.

Adjustment to Monthly Benefit Amount at FRA

When beneficiaries file for retirement benefits before their FRA, their monthly benefits are reduced by the number of months they are under FRA at the time of entitlement. Suppose beneficiaries lose benefits for one or more months before attaining FRA due to earnings tests. In such cases, the SSA will adjust their benefits at FRA to reflect the number of months for which some or all or their Social Security benefits were lost.

Example: Suppose Jane lost her job at age 62 and she filed for her retirement benefits. Because her Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) was $2,000, and her FRA is 66, she receives reduced retirement benefits of $1,500, ([1 – 0.25] $2,000), where the 25 percent reduction from PIA reflects reduction for beginning benefits 48 months before her FRA. In particular, her reduced benefit fraction is ([1 – 36(5/9 percent)] – [12(5/12 percent)]), which reflects 36 months of reduced benefits at 5/9 th of 1 percent of PIA per month, plus an additional 12 months of reduced benefits at 5/12 th of 1 percent of PIA per month.

At age 63, she gets another job and works for about two years before retiring. Suppose this job causes her to lose all or partial Social Security benefits for 18 months. When she attains FRA, the SSA will adjust her monthly benefit fraction to reflect the 18 lost or partially lost months of benefits. At her FRA, her benefit fraction increases to 83.33 percent (1 – 30[5/9 percent]), which reflects 30 months of reduced benefits. So, she gets 83.33 percent of her COLA-adjusted PIA.

Moreover, other benefits based on her earnings record, including her husband’s spousal and survivor benefits and her child(ren)’s benefits, would be based on this adjusted benefit fraction. Because of this adjustment at FRA, many financial planners seem to think that the earnings test will not hurt their clients. As will be explained next, the additional benefits at FRA approximately offset lost benefits due to the earnings test only if the client lives to about age 80. However, most clients have life expectancies that are either significantly shorter or significantly longer than 80.

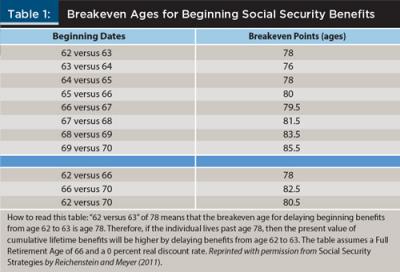

Table 1 presents the breakeven ages for starting Social Security benefits assuming the real return on Treasury bonds is 0 percent, which it has been since late 2008.4 The “65 versus 66” of 80 means that the breakeven age for delaying benefits from age 65 to 66 is age 80.

Mathematically, assuming a 0 percent real yield, the present value of lifetime benefits if begun at 65 is 0.9333 (PIA [12 months] [x years]), while the present value if begun at FRA is PIA (12 months) (x – 1 years), where x is the breakeven time period. The 0.9333 fraction denotes the 0.0667 reduction in benefits for beginning 12 months before FRA. Setting these two amounts equal and solving indicates that x is 15, which means the breakeven age is 15 years after age 65 or at 80 years. Therefore, if a single individual has a life expectancy of more than 80 years and wants to maximize the present value of expected lifetime benefits, they should begin benefits at 66 instead of 65. The other breakeven ages in Table 1 are calculated similarly.

As emphasized in Reichenstein and Meyer (2011), the key takeaway from Table 1 is that the breakeven age tends to be slightly before age 80 if benefits begin before FRA, and slightly after 80 if benefits are delayed until after FRA. The earnings test does not apply to people who are at least FRA; it will only affect singles who want to begin benefits before FRA. Consequently, the earnings test should primarily affect singles with life expectancies below age 80. After all, if they have life expectancies above age 80, then they generally will choose to delay their Social Security benefits until at least FRA.

Consider again the example for Jane. Recall that Jane began Social Security benefits at age 62, returned to work, and at FRA had her benefits adjusted to 0.8333 of her PIA to reflect lost or partially lost benefits for 18 months. Assuming a 0 percent real yield, the breakeven age between starting benefits at 62 and 18 months later at age 63.5 is 77.55 Therefore, she must live to at least age 77 for the higher monthly benefit starting at FRA to offset the 18 months of lost benefits. The fact that Jane began her benefits at age 62 suggests that she probably has a short life expectancy and is not likely to live beyond this breakeven age of 77.

Table 1 can also be applied to a married couple. After the death of the first spouse, the surviving spouse generally will continue benefits based on the higher-earner’s record, while benefits based on the lower-earner’s record generally will cease. This leads to two rules. First, to maximize the couple’s expected lifetime benefits, the higher-earning spouse should begin his or her retirement benefits based on the age he or she would be when the second spouse is expected to die.

Second, the lower-earning spouse should begin his or her retirement benefits based on the age he or she would be when the first spouse is expected to die. As Reichenstein and Meyer (2011) emphasized, the first rule is a strong generalization and applies except in rare situations. In contrast, the second rule sometimes applies. Due to the complex rules surrounding spousal benefits and survivor benefits, to maximize a couple’s expected lifetime benefits, the lower earner often should begin retirement benefits at a different date than the date suggested by this second rule. Following this second rule, if the lower earner would be young when the first spouse is expected to die, then it usually pays for the lower earner to begin benefits before FRA.

Example: Assume Nancy is the lower earner and has an above-average life expectancy of age 90. George, her husband, is six years older with an average life expectancy of 83. To maximize this couple’s lifetime benefits, George should delay his retirement benefits until age 70, because he would have been 96 when Nancy is expected to die. Furthermore, Nancy may want to begin her retirement benefits before FRA. After all, she would be 77, which is a shorter-than-average lifetime, when George is expected to die. Benefits based on her earnings record will cease at the death of the first spouse. Thus, the earnings test may apply to couples even when neither partner has a below-average life expectancy.

Example: It is worth noting one other time when the earnings tests may come into play. Suppose Betty loses her job at age 62 and begins her Social Security benefits at that time. At age 63.5, she rethinks her decision to begin benefits at 62. She recently read that, due to her long life expectancy, she should have delayed her benefits until 70. Although she would like to undo her age 62 decision, because more than one year has passed since she began her benefits, she cannot cancel this decision. However, if she returns to work, she may be able to improve her situation. In particular, if she returns to work and earns a healthy income, she could lose all benefits through FRA due to the annual earnings test. At FRA, her benefits will be increased to the level they would have been had she started her benefits 18 months before FRA. Moreover, beginning at her FRA, she has the option to suspend her benefits. Later, at say age 70, she could reinstate her benefits. In this fashion, her reinstated benefits would be at the level they would have been if she initially began her benefits at age 68.5. In this fashion, Betty could undo most of the adverse consequences of her ill-advised decision to begin benefits at age 62.

How Maximizing Claiming Strategy Could Be Impacted by Earnings Tests

This section presents three examples of how the earnings tests could affect a client’s maximizing Social Security claiming strategy. The maximizing claiming strategy is defined as the approach that maximizes the present value of lifetime benefits if the single individual lives to his or her precise life expectancy, or each partner of a married couple lives to their life expectancies. The first example considers a single individual whose maximizing claiming strategy is affected by an earnings test. The latter two examples consider couples where, respectively, the high PIA spouse and low PIA spouse’s earnings affect the claiming strategy.

As emphasized in Reichenstein and Meyer (2011), most clients should consider two criteria when selecting their claiming strategy. First, what claiming strategy would maximize the present value of expected lifetime benefits? Second, what strategy would minimize longevity risk, which is the risk of running out of funds in their lifetimes? Sometimes there is a trade-off between these two criteria. In such cases, retirees must subjectively determine their optimal trade-off between these two.6 The maximizing strategy is presented in this paper because this is an objective criterion.

Example: Single individual. Jenny is 62 years old and single. She has a PIA of $2,000, a life expectancy of age 77, and an FRA of 66. According to Table 1, she would maximize the present value of expected lifetime benefits by claiming benefits before her FRA. However, if she continues to work and earns at least a moderate income, then the earnings test will eliminate all her benefits if started before her FRA. In essence, due to the earnings test, her claiming decision is restricted to beginning benefits sometime between FRA and age 70. Because the breakeven age in Table 1 for starting her benefits at FRA or age 67 is age 79.5, her maximizing strategy in the face of the earnings test would be to claim her retirement benefit at her FRA.

Example: Couple with a spouse with a high PIA. Mike was born December 2, 1950, has a PIA of $2,400, and a life expectancy of age 76. His wife, Frances, was born December 2, 1953. She has a PIA of $900 and also has a life expectancy of age 76 (a life expectancy of 76 means they are expected to die in the month they turn age 76). Their FRA is 66. Mike has substantial earnings, while Frances is retired.

The second through fourth columns of Table 2 present their maximizing strategy if earnings tests did not apply with benefit amounts expressed before COLA adjustments.7 Based on life expectancies and the breakeven ages in Table 1, Mike should claim retirement benefits in December 2015—the month he turns 65—because he would have been 79 when Frances is expected to die. His benefits would be $2,240 per month.

In December 2015, Frances turns 62. This is the month she should claim her retirement and spousal benefits because she would be 73 when Mike is expected to die. Her monthly benefits total $885. After Mike’s death in December 2026, Frances continues his benefits of $2,240 per month.8 Unfortunately, the earnings test prevents them from selecting this claiming strategy because Mike’s earnings between age 65 and his FRA would affect both his retirement benefits and Frances’ spousal benefits.

Given the earnings test, the last three columns of Table 2 present their maximizing strategy. It calls for Frances to claim her retirement benefits at age 62 of $675 per month (because Mike has not yet filed for his benefits, Frances is not yet eligible for spousal benefits). At his FRA, Mike claims his retirement benefits of $2,400 per month and Frances adds spousal benefits at that time for total benefits of $900 per month. After Mike’s death, Frances continues his benefits of $2,400 per month.

As shown in Table 2, the earnings tests are expected to reduce the present value of their lifetime benefits by about $2,640. As a generalization, because the higher PIA spouse’s substantial earnings would affect his or her retirement benefits and his or her partner’s spousal benefits, the earnings tests prevent him or her from filing for benefits until the earlier of when he or she retires from work or turns FRA (in this example, when Mike turns FRA).

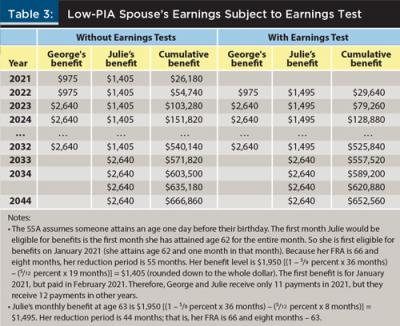

Example: Couple with a spouse with a low PIA. George was born December 10, 1952, has a PIA of $2,000, and a life expectancy of age 80. Julie, his wife, was born six years later on December 20, 1958. She has a PIA of $1,950 and a life expectancy of age 85. George’s FRA is 66, while Julie’s is 66 and eight months. Julie has substantial earnings but will retire at age 63. George is retired.

The second through fourth columns of Table 3 present their maximizing strategy in the absence of earnings tests with all dollars expressed before COLA adjustments. Julie claims retirement benefits of $1,405 per month in January 2021 at age 62 and 1 month, the earliest month she can file for benefits. George files for spousal benefits that same month at age 68 and 1 month. At age 70, George switches to his retirement benefits.9 After George’s death, Julie receives survivor benefits of $2,640 per month. Unfortunately, this strategy is not possible because Julie’s substantial earnings would eliminate both her retirement benefits and George’s spousal benefits until she retires at age 63.

Given the earnings tests, their maximizing strategy is for Julie to claim retirement benefits of $1,495 per month when she retires at age 63 and for George to file for spousal benefits that same month at age 69. At 70, George switches to his retirement benefits. After George’s death, Julie receives survivor benefits of $2,640 per month. Julie’s earnings prevent her from claiming benefits before she retires at age 63. George cannot get spousal benefits until Julie files for her retirement benefits. Therefore, he must wait until she files for retirement benefits before he can file for spousal benefits.

As a generalization, the lower-earning spouse should file for benefits at the earlier of when she or he retires from work or turns FRA (in this case when Julie retires from work at 63). Thus, George cannot file for spousal benefits until he is age 69, which is 11 months later than in the maximizing strategy if there were no earnings tests. The earnings tests reduced this couple’s expected lifetime benefits by more than $14,000.

Conclusion

It is very common for financial planners to face situations where a client’s earnings (assumed male for convenience) would affect his retirement benefits, his wife’s spousal benefits, and perhaps their child(ren)’s Social Security benefits. In addition, the wife may have earnings, which could impact her retirement benefits, her spousal benefits, and, if her husband should predecease her, her survivor benefits. Naturally, these clients will look to their financial planner to help them figure out how their earnings should affect their Social Security claiming strategy. In addition, clients expect their financial planner to help them navigate the earnings tests, including how and when to report estimated earnings. This study provides financial planners with this information by illustrating examples of how the earnings test could impact the Social Security claiming strategy that maximizes the present value of projected lifetime benefits.

Endnotes

- The Social Security Administration considers someone to attain an age one day before their birthday. If Peggy’s 66th birthday occurs on June 2 through July 1, 2015 then she attains FRA in June 2015. In contrast, if she was born on June 1 then she attains FRA in May 2015.

- Suppose Peggy earned $50,000, as expected, from January through May and that she earned $100,000 in the remainder of the year. If Peggy does not report her January through May earnings, then the SSA would assume her 2015 W2 earnings of $150,000 were evenly distributed through the year. The Social Security Administration would assume Peggy earned $12,500 per month and $62,500 from January through May. Thus, she should report her actual earnings of $50,000 through May to her local SSA office.

- The definition of “highly skilled occupation” does not appear to be well defined. Code RS 02505.065 in the SSA’s Program Operations Manual System (POMS) says, “The beneficiary devotes 15 hours or more per month to managing a large business or engages in a highly skilled occupation. In such cases, the services could be considered substantial.”

- A long line of scholars have concluded that the risk-appropriate real (inflation-adjusted) discount rate for calculating the present value of Social Security benefits is the real yield on a TIPS bond, where the duration of the TIPS bond equals the duration of Social Security benefits. Social Security benefits and cash flows on TIPS bonds are both linked to inflation. See Fraser, Jennings, and King (2001), Jennings and Reichenstein (2001, 2008), Reichenstein (2001), Reichenstein and Jennings (2003), and Reichenstein and Meyer (2011). Since 2008, the real yield on 10-year TIPS has been approximately 0 percent. We used the 10-year TIPS bond because its duration is 10 years, which is about the same as the duration of Social Security benefits for 20 years, and the life expectancy of a mid-60s retiree is about 20 years. As of August 15, 2014, the real yield on 10-year TIPS bonds was 0.14 percent.

- Set 0.75PIA (12 months) (x years) = 0.8333PIA (12) (x – 1.5) and solve for x of 15. Thus, the breakeven age is 15 years beyond 62, or age 77.

- Guidance is provided at www.ssanalyzer.com to assist financial planners help their clients see the trade-off between these two criteria, so their clients may make an informed decision between alternative strategies.

- Benefit amounts before COLAs are shown. These are the approximate present values because the real discount rate is about 0 percent. These amounts express future benefits in terms of today’s purchasing power. For example, if next year’s annual COLA is 2 percent, then next year’s nominal benefits would be 2 percent higher, but so would prices. Next year’s COLA-adjusted benefit amount would buy the same amount of goods and services as this year’s benefit amount.

- Because Mike died in December 2026, he does not receive a benefit for that month. Rather, Frances would receive survivor benefits for December 2026, but this benefit will be paid in January 2027.

- Based on life expectancies, benefits based on Julie’s record will last until she is age 74 (at George’s death), while benefits based on George’s record will last until he would have been 91 (at Julie’s death). As such, he delays his benefits until age 70.

References

Fraser, Steve P., William W. Jennings, and David R. King. 2001. “Strategic Asset Allocation for Individual Investors: The Impact of Present Value of Social Security Benefits.” Financial Services Review 9 (4): 295–326.

Jennings, William W., and William Reichenstein. 2001. “Estimating the Value of Social Security Retirement Benefits.“ Journal of Wealth Management 4 (3): 14–29.

Jennings, William W., and William Reichenstein. 2008. “The Extended Portfolio in Private Wealth Management.” Journal of Wealth Management 11 (1): 36–45.

Merrill Lynch (in partnership with Age Wave). 2014. “Work in Retirement: Myths and Motivations.” Retreived from www.wealthmanagement.ml.com/publish/content/application/pdf/GWMOL/MLWM_Work-in-Retirement_2014.pdf

Reichenstein, William. 2001. “Rethinking the Family’s Asset Allocation.” Journal of Financial Planning 14 (5): 102–109.

Reichenstein, William, and William W. Jennings. 2003. Integrating Investments and the Tax Code. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2011. Social Security Strategies. Overland Park, KS.

Citation

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2015. “Social Security’s Earnings Tests: A Primer for Financial Planners.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (1): 53–60.