Journal of Financial Planning: July 2013

The bypass trust, also known as the B trust or credit-shelter trust, has long been used as a key element in estate planning for wealthier families. Structured properly, this trust usually provides the surviving spouse income and the limited right to invade trust corpus while avoiding estate taxation after the first spouse’s death. It does so by allowing the first decedent to use their $5.25 million exclusion—the new applicable lifetime exclusion amount for 2013 thanks to the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (Act of 2012).

The bypass trust also permits the surviving spouse access to those funds while avoiding estate inclusion at the surviving spouse’s later death. The Act of 2012 also made the portability feature permanent. Therefore, the only real change for estate and gift taxes from 2012 to 2013 is the adjustment in the top tax rate from 35 percent to 40 percent. So the question is: does the bypass trust still make sense in this new estate tax environment?

To answer that, let’s first use an example to illustrate why the bypass trust was such a powerful vehicle before portability, then consider the benefits and drawbacks of using bypass trusts today.

Assume, under the prior law, that Sally and Frank each have $5.25 million of assets in their individual names. If Sally were to die and leave all of her assets to Frank, she would not use any of her exemption, the transfer is tax-free under the marital deduction, and Frank would now own $10.5 million. When Frank dies he will not incur an estate tax liability on the first $5.25 million of his estate, but he will incure taxation on the second $5.25 million, the amount left to him by Sally. Sally has effectively “wasted” her exclusion or “over-qualified” her marital deduction.

If Sally leaves her assets to a bypass trust for the benefit of Frank, rather than outright to Frank, her assets will not be included in Frank’s gross estate; her estate will not be subject to estate tax due to her lifetime exclusion amount of $5.25 million; Frank’s estate will not incur any estate tax liability because his total assets of $5.25 million are covered by his exclusion. This saves Sally and Frank’s successors $2,045,800 of estate tax based on 2013 tax rates.

Under current law, with portability, if Sally left all of her assets to Frank outright, Frank would still have an estate of $10.5 million. This is no longer a problem because Sally’s unused exclusion of $5.25 million may be used by Frank along with Frank’s own $5.25 million exclusion. Frank’s estate will not have an estate tax liability because the full $10.5 million is sheltered.

Give Credit to the Credit-Shelter Trust

Not surprisingly, the bypass trust has lost its luster with many planners and estate attorneys, however, the bypass trust could still play an important role in estate planning for a number of reasons.

Protecting subsequent spouses. The portability on the estate exclusion specifically states that the deceased spousal unused exclusion amount (DSUEA) is that amount not used by the last spouse to die. Therefore, in the event that a surviving spouse remarries and is predeceased again, the unused exclusion amount from the first decedent spouse is wasted.

Continuing with our previous example, assume that Sally predeceases Frank without using any of her lifetime exclusion amount and Frank eventually remarries, this time to Betty. Frank has $10.5 million in assets and let’s assume that Betty has $5.25 million of her own assets. If we assume Betty predeceases Frank and leaves all of her assets to Frank, Frank will then die with $15.75 million in assets. Sally’s unused exclusion is wasted, but Frank’s estate can use Betty’s unused lifetime exclusion amount. Therefore, Frank’s estate would escape tax on the first $10.5 million and pay tax on the remaining $5.25 million.

If Sally had left the assets in a bypass trust, she would use her lifetime exclusion of $5.25 million and Frank could use $10.5 million—Betty’s unused exclusion plus his exclusion, therefore avoiding all estate taxes. If Betty also uses a bypass trust, then Betty will use her $5.25 million exclusion and Frank would use his own. Ultimately, the difference in this planning will equate to estate tax savings on $5.25 million.

A potential way around the bypass trust in this situation is gifting. The temporary regulations¹ state that any taxable gifting made by the surviving spouse will first utilize the unused exclusion from the most recently deceased spouse. So if Frank married Betty after Sally died and Betty’s not doing too well from a health perspective, Frank can gift up to $5.25 million to his heirs, allowing him to use Sally’s unused exclusion. Then, after Betty has passed away, he can use Betty’s unused exclusion and his own exclusion to pass the remaining $10.5 million to his heirs at his death.

Asset protection. Varying trust structures can be used as a means of insulating wealth from creditors and lawsuits. A bypass trust can be created simply through the will of the decedent to assist in shielding assets.

While self-settled asset protection trusts have begun creeping up in states across the country, a case like Evseroff² may have individuals worried about the viability of this solution. A better solution is if the trust is created and funded by another individual, such as through a bypass trust. The protection granted in these trusts will vary from state to state, and all parties involved must understand how the trust works, its limitations, and how to best guard against seizure.

Transfers two or more generations removed. While the estate exclusion is re-united with the gift and generation-skipping transfer (GST) taxes, the portability only applies to the estate exclusion. This is important for transfers to those two or more generations removed, because the surviving spouse is limited to their $5.25 million exclusion regardless of what was used by their decedent spouse.

The bypass trust is a method for allowing the surviving spouse income and limited access to the trust corpus, while providing that the trust remainder pass to grandchildren or other future generations. If a bypass trust is not used, the first decedent would have to pass the assets directly to skip generations, although direct outright transfers are generally not recommended because of the lack of control.

Sally could leave her $5.25 million to her grandchildren through her estate directly. The bequest would escape estate tax because of the lifetime exclusion amount on estate taxes, and it would escape GST tax because of the $5.25 million lifetime exclusion amount on generation-skipping transfers. The downside is that her husband, Frank, would not get to benefit from these assets during his life.

If she left those assets directly to Frank for him then to leave to their grandchildren, Sally’s GST lifetime exclusion is wasted. Instead, if Sally left the assets in a bypass trust for the ultimate benefit of the grandchildren, she would use her estate and GST exclusions, meaning Frank is still available to use his own GST exclusion.

Preventing accidental disinheritance. With a trust, the ultimate beneficiary is known at the first death. This is useful for protecting children and grandchildren from being accidentally disinherited if the surviving spouse remarries. In a remarriage, the new spouses often commingle assets and redraft estate documents to provide financial assistance to their new spouse. If done improperly or without care, the children of the original decedent may not receive anything.

The trust also protects the ultimate beneficiaries from the surviving spouse being scammed or otherwise taken advantage of by less-than-savory folks. It also can assist in stretching assets provided that the surviving spouse merely lives off the income.

Professional management. Many times, the income-earning spouse dies first leaving the survivor with money but no direction on how it should be invested to last a lifetime. The bypass trust could be established with a trustee who, if properly selected, can provide guidance on professional management of the assets left behind.

Spendthrift provisions. For spouses who are or could become a spendthrift, the trust can establish guidelines on the amount to draw, when it can be drawn, and any restrictions on access. Spendthrift provisions also may prevent beneficiaries from assigning their interest in the trust to creditors as collateral or in settling legal suits.

Avoiding probate. Assets inside the bypass trust will avoid probate upon the death of the surviving spouse. If all assets are left to the surviving spouse outright, they will pass through the probate court. Although there are several benefits to the probate process, it is generally advisable to avoid it if possible, considering it can be costly and time consuming.

Growth outside the estate. Future growth remains outside of the gross estate on the second death. Generally, clients wish to avoid estate taxes and pass as much on to heirs as possible. The issues planners face here are higher income tax rates at the trust level versus the individual level, and the loss of any step-up in basis at the surviving spouse’s death.

Assume that Sally dies in 2013 with $5.25 million and Frank has $5.25 million of his own. Assume he earns 5 percent per year and pays tax on 40 percent of the earnings each year at 15 percent, making his after-tax rate of return 4.7 percent; inflation is

2 percent; and he lives on $100,000 per year. Then, assume a probate cost of

2 percent on assets held by the surviving spouse. After 10 years, the $10 million will equate to roughly $15.2 million, or about $13.4 million after estate taxes.

Even if the lifetime exclusion is indexed for inflation (2 percent a year), which is provided by the current law,³ Frank’s estate will incur an estate tax if he were to die even after the first year.

On the contrary, if Sally used a bypass trust, Frank could use his own assets for living expenses and amass the assets Sally left for their family. For this example, we have to include several new factors, namely higher income taxes during life and no step-up in basis at death. Therefore, assume that 40 percent of the earnings are taxed at 43.4 percent (39.6 percent maximum tax rate plus the 3.8 percent Medicare surtax) making the after-tax rate of return a little more than 4.13 percent. The same 2 percent probate cost applies to the assets held by the surviving spouse but does not apply to the trust assets as they would circumvent this process. Furthermore, any gains would be taxable to the heirs because there is no step-up in basis at the death of the surviving spouse on the bypass trust’s assets. To incorporate this, all gains in the bypass trust are assumed long-term in nature and taxed at 15 percent in year 10.

This strategy, while it would not remove the estate tax completely, would significantly reduce the family’s estate tax liability. After estate taxes on the survivor’s assets and capital gains taxes on the trust assets, the total after-tax balance to heirs is about $13.9 million; that’s about $530,000 more than the previous example in which Sally did not use a bypass trust.

Downsides of the B Trust

Besides the lack of a second step-up in basis, other drawbacks to the bypass trust exist.

Direct costs. After checking with several attorneys in the Atlanta area, the price range for a basic bypass trust provision is $750 to $1,000. This is likely significant for average Americans.

There is typically an additional cost in trust management of the assets when a corporate trustee or investment manager is involved. These services will likely cost 1 percent of assets or less depending on total trust assets managed. This cost is not built into the previous examples under the perhaps optimistic assumption that professional management will at least cover their cost in additional performance. It also is likely that the surviving spouse would use professional management for assets passed outside of a trust.

Limited access. The bypass trust limits the surviving spouse’s outright access to the assets. As stated earlier, this can be a good thing, but it can also be problematic should the surviving spouse wish to make a big purchase.

Compressed income tax brackets. Trust income tax brackets are similar to an individual’s except they are much more compressed. The top tax rate of 39.6 percent begins at $11,950 of income not distributed to the beneficiaries, and the 3.8 percent Medicare surtax also comes into play at that level. Therefore, it is a huge disadvantage in comparison to that income being taxed at an individual’s level, where the 39.6 percent bracket doesn’t begin until $400,000 of income.

If the income is distributed each year, the trust gets a deduction known as Distributable Net Income (DNI). The income is then picked up by the beneficiary on a Schedule K-1. Although this seems like a reasonable method of avoiding the trust income tax problems, it negates the purpose of sheltering the future growth of the bypass trust from estate taxes. If the surviving spouse was going to take all of the income from what was left behind, why not just use the portability provision? The estate tax would be the same either way, the income tax would be the same, and the step-up in cost basis—or lack thereof—would be the same. The only portion that would benefit from the trust setup is the unrecognized growth over time.

A potential cost to heirs. The basis of assets included in the estate of a decedent is generally stepped to the fair market value on the date of death. In an appreciating market environment, this generally means a step-up in basis from the purchase cost to the higher value at death.

The difference between using the bypass trust and simply using the portability feature has nothing to do with the step-up in basis at the first decedent’s passing. Instead, it has to do with the step-up when the surviving spouse passes, because the assets inside the bypass trust will not be included in their estate at death. Thus, the heirs who inherit the bypass trust assets will inherit a basis equal to the fair market value on the date of death of the first spouse to pass. This means any unrecognized gains inside the trust eventually will have to be paid by the heirs.

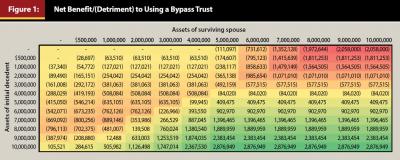

The effect of the trust tax and lack of step-up in basis causes a lot more confusion in deciding whether to use the bypass trust. Based on the same assumptions used in the previous examples, Figure 1 is a heat map showing at what asset levels it makes sense to use the bypass trust (positive values/green cells) and when it is more advantageous to use the portability feature (negative values/red cells).

At lower asset levels—generally less than $9 million between both spouses—it makes sense to use the portability feature and forgo the bypass trust. Keep in mind that the heat map uses a 10-year time horizon between the death of each spouse, not considering remarriage, specific tax rates and rates of return, certain income needs, inflation rates, and probate costs. Individual decisions will certainly change as these factors change.

Although the portability of the lifetime exclusion amount diminishes the effectiveness of the bypass trust, planners should not disregard the trust entirely. A number of benefits and drawbacks exist. And because every state has different laws for inheritance, gifting, income, and other taxes, individual state impact has not been included in this analysis. Like most things in financial planning, this is a situation where one size does not fit all.

Bryan Strike, CFP®, CPA/PFS, is a financial planner at Kays Financial Advisory Corp. and an instructor for Kaplan University. He holds a Master of Taxation degree and a Master of Science in personal financial planning.

Endnotes

- Temporary Regulation 25.2505-2T(b).

- United States v. Evseroff, 2007- U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH), rev’d and rem’d y 2008-1 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH).

- IRC Section 2010(C)(3)(B) as amended.