Journal of Financial Planning: July 2015

Michael Finke, Ph.D., CFP®, is a professor and Ph.D. coordinator in the Department of Personal Financial Planning at Texas Tech University. He is director of the retirement planning and living cluster at Texas Tech University. He is also a two-time recipient of the Journal’s Montgomery-Warschauer Award.

Wade D. Pfau, Ph.D., CFA, is a professor of retirement income at The American College and a principal at McLean Asset Management. He hosts the Retirement Researcher website (www.RetirementResearcher.com) and is a two-time recipient of the Journal’s Montgomery-Warschauer Award.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Northwestern Mutual for sponsoring this research, as well as the constructive feedback from Gregory Jaeck, Ron Nelson, and Ed McGill.

Executive Summary

- Most deferred income annuities (DIAs) have a relatively short deferral period, making them particularly appealing to clients nearing retirement who value the ability to plan on a fixed, nominal income stream after retirement.

- Unlike long-term deferral period annuities (longevity insurance) that are primarily meant to protect against longevity risk, a short-term deferral period annuity can provide a steady income to pre-fund retirement spending over the entire retirement life cycle.

- The purchase of a DIA before retirement is particularly valuable for clients who would have maintained a stock allocation lower than 70 percent. Retirees would have been better off without a DIA in simulations where portfolio returns are very high or when retirees die early.

- Findings suggest that short deferral period annuities can reduce the cost of funding retirement, provide longevity protection, and offer behavioral benefits to clients concerned about near-retirement market performance.

Clients nearing retirement have increasingly been attracted to products that allow them to buy future income with recent portfolio gains. Taking assets out of a portfolio to buy a product that has a pre-defined return has important portfolio implications that should be considered by financial planners when constructing a retirement income strategy with the remaining wealth. Buying a guaranteed income also reduces risk at a time when a bear market can derail a retirement income plan.

This study uses a methodology proposed by Milevsky (2006) to evaluate the impact of guaranteed income products on the cost of funding retirement and shows when, and for which clients, a deferred income strategy makes sense.

Understanding DIAs

The significant majority of deferred income annuities (DIAs) purchased today have a relatively short deferral period before annuity payments begin. This suggests that DIAs are particularly appealing to clients nearing retirement who value the ability to plan on a fixed, nominal income stream after retirement. Unlike long-term deferral period annuities that are meant to provide late-life income primarily to protect against longevity risk, a shorter deferral period annuity (hereafter called a short deferral annuity) is purchased to provide a steady income to fund retirement spending over the entire retirement life cycle.

Fixed short deferral DIAs may more easily be viewed as a portfolio whose return is guaranteed for a period of time after which a single premium immediate annuity is purchased. The primary advantage of a short deferral annuity is the ability to establish a defined minimum level of retirement spending. In other words, a client can set aside a portion of retirement savings today to buy a guaranteed retirement income in the near future. For clients who have experienced significant recent gains in their investment portfolio, this ability to buy income may be particularly attractive in order to ease concern that a bear market right before retirement will reduce income security.

Although the desire to lock in a secure income may be driving demand for short deferral annuities, their impact on retirement portfolios has not been thoroughly examined in the financial planning literature. Previous research, including Pfau (2011) and Pfau (2014), suggests that portfolio returns right before retirement have an outsized influence on retirement income sustainability. This sequence of return risk means that a bear market near retirement increases the risk of outliving assets far more than a bear market later in retirement. Pfau (2013) found that the purchase of a single premium immediate annuity can serve as an efficient substitute for the fixed income portion of a retirement portfolio by better protecting a spending level on the downside while also increasing the average legacy value of assets.

Setting assets aside before retirement to buy a fixed deferred annuity places a portion of the retirement portfolio into a bond-like investment. The funds used to buy a fixed income annuity should be viewed as a bond investment when evaluating a holistic retirement portfolio. For example, if 20 percent of a 50/50 retirement portfolio is invested in a fixed annuity, then the equity portion of the retirement portfolio should be increased (in this case to 50/30, or 62.5 percent) to maintain the appropriate amount of investment risk.

Allocating funds to purchase an annuity in the future allows a near-retiree to invest in a portfolio of bond-like assets within the DIA whose duration matches anticipated future spending needs. Depending on the age of the investor during the deferral period, additional mortality credits may improve the expected return on fixed income investments prior to the initiation of annuity payments.

The amount of future income one can buy for each dollar invested in a DIA depends on the client’s age, and the number of years between purchase and when the income stream begins. A longer deferral period will allow a client to buy a larger annuity payment because (1) assets have more time to grow; (2) there will be fewer years of distribution; and (3) more mortality credits are available.

This paper discusses the use of deferred income annuities within a retirement income plan. When developing the model, we assumed an income strategy in which an investment portfolio is gradually decumulated over time to fund retirement living expenses. We followed the method proposed by Milevsky (2006) to estimate the present value cost of funding a retirement income given randomness for both asset returns and longevity. This allowed us to simulate thousands of retirement paths in order to show how allocating a portion of a retirement portfolio to a short deferral annuity before retirement affects the cost of retirement for a broad range of lifespans and market returns.

Methodology

Retirees do not know how long they will live. They also do not know what stock and bond returns will be realized in the future. One way to estimate the potential value of a DIA is to see how ownership would have impacted the cost of retirement in longer and shorter lifespans, during bull and bear stock markets, and during periods of high and low inflation.

In this study, we estimated the average cost of retirement by simulating 50,000 retirements with random longevity and asset returns in order to better understand the impact of partial deferred annuitization on a retirement income plan.

The cost of retirement, also known as the stochastic (or random) present value of retirement, was the actual cost of paying for a given income in retirement when the unknown variables of longevity and asset returns were allowed to occur by chance. The stochastic present value of retirement was the current amount of assets a couple would require today (assuming no future savings) to meet their desired retirement expenses. In other words, a retired couple who does not live very long in retirement and experiences high portfolio returns will have a very low cost of funding a desired level of spending. Couples who live a long time and experience modest portfolio returns will need to have saved more by retirement to fund their spending.

Each simulation had a random age of death for the last remaining survivor in a couple, and a specific sequence of stock and bond returns over the couple’s remaining lifetime. Milevsky (2006) provided a more mathematical treatment of the stochastic present value concept.

Simulated ages of death. To simulate the costs for retirement, we required simulations for survival and market returns. Survival was calculated using the Society of Actuaries’ RP-2014 Mortality Tables draft for healthy annuitants. Mortality rates were provided for males and females. Joint survivorship was simulated assuming independence for the ages of death with each member of the couple. In 5 percent of cases, both spouses were assumed to be deceased by age 73, however 50 percent of couples had at least one member live to at least age 87, and 5 percent of couples had at least one member live to age 99.

Simulated asset returns. We assumed that financial assets were held in a portfolio of stocks and bonds with annual rebalancing to the targeted asset allocation and a 1 percent annual fee to cover fund management costs and advisory fees.

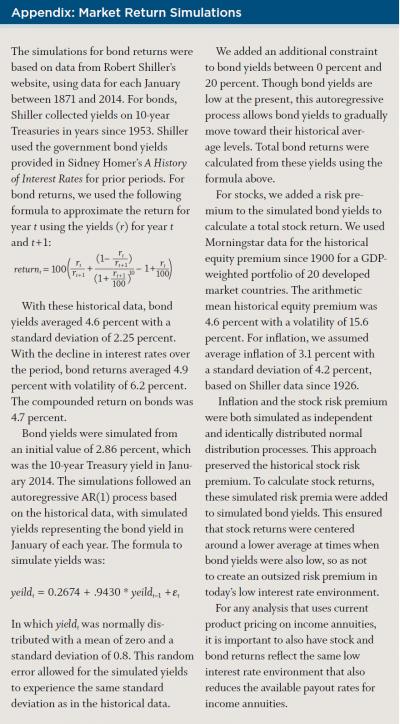

The data used to guide the capital market simulations came from Yale University professor and Nobel laureate Robert Shiller’s website (www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.htm). The investment portfolios included large capitalization stocks (S&P Composite Stock Price Index) and long-term U.S. government bonds. Additional information about the return simulation assumptions can be found in the Appendix at the end of this article.

Simulating the cost of retirement. Based on 50,000 ages of death for the second member of the couple, as well as 50,000 sequences of asset returns through each age of death, we were able to investigate the present value for the cost of retirement based on different asset allocation and product allocation strategies. The stochastic present value was the amount of assets required today to successfully finance a retirement-spending objective through death based on the actual age of death and the experienced portfolio returns. It assumed no additional contributions were made in the future and no money remains at death.

These retirement costs could only be known in hindsight, but they reflect the amount of assets a retiree requires today in order to ensure a successful retirement. A strategy that lowers the cost of retirement is desirable in the sense that it increases the probability that the retiree will have enough assets to support retirement. A higher age of death (because this requires spending support for more years) and poor market returns will each lead to higher costs of retirement in terms of the amount of assets needed to be set aside today. There is an entire distribution of outcomes for the costs of retirement. We focused on different parts of the distribution to obtain an idea about the upside potential and downside risks associated with different strategies.

For ease of analysis, we assumed that retirees want $100,000 of inflation-adjusted spending for each year that at least one member of the couple remained alive in retirement. We considered cases in which only a financial portfolio with stocks and bonds was used to support retirement, and cases in which 50 percent of the bond allocation in the median case (with a maximum of $500,000) was used today to purchase a DIA. Three primary scenarios were tested:

- A 45-year-old couple planning to retire at age 65 (20-year deferral period)

- A 55-year-old couple planning to retire at age 65 (10-year deferral period)

- A 62-year-old couple planning to retire at age 65 (three-year deferral period)

The baseline case was the 55-year-old couple, as it reflects the most common use of DIAs purchased today. We assumed at least one member of the couple survived to the retirement age, because the premium would otherwise be refunded and the probability that both members of a couple would not live this long is negligible.

For cases with partial annuitization, we added the premium paid for the income annuity to the cost of retirement. We then subtracted any income received from the income annuity from the desired spending amount for any year in retirement that the annuity provided income. The financial portfolio was used to fill in the income gap not covered by the income annuity. When partial annuitization was not employed, the financial portfolio must cover the full cost of retirement. In the rare case that the real value of income provided by the income annuity exceeded the desired spending target for any year, the excess income from the income annuity was returned to the financial portfolio, which further helped to reduce the total cost of retirement.

Deferred Income Annuity Quotes

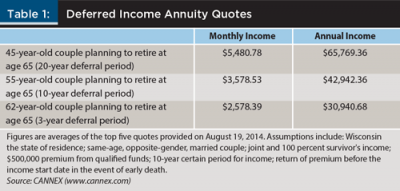

Table 1 shows DIA quotes provided by CANNEX, an annuity quote service. The quotes are averages of the top five quotes provided on August 19, 2014. These quotes were for nominal income, did not make adjustments for inflation, and were current when this paper was written.

Qualified funds were used to purchase income starting at age 65. The DIA quotes included the return of premium benefit in the event of death before the income start date and a 10-year period certain for income payments after the income start date. In the event that the second member of the couple passed away after income began but before the full 10 years of period-certain payments were received, we lowered the cost of their retirement by the present value of any remaining period-certain payments that would be included as part of the couple’s legacy.

Baseline Results: Investment Portfolios with DIAs

The distribution of the calculations for the stochastic present value of retirement allowed us to investigate the efficient frontier for retirement income with and without the use of a DIA, and to further determine whether partial annuitization was able to broaden the frontier to create more efficient retirement outcomes.

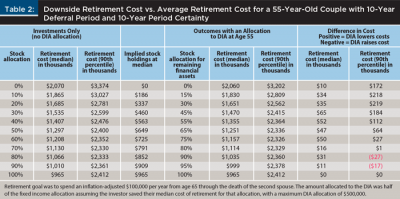

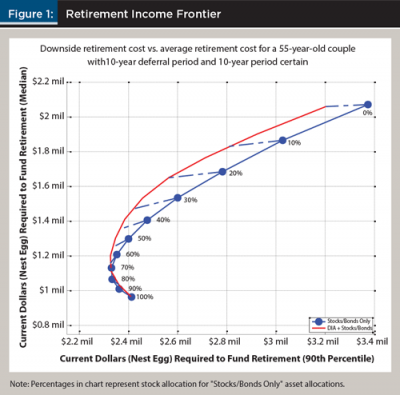

Table 2 provides the numbers, while Figure 1 provides a visual display of the numbers for the baseline 55-year-old couple planning to retire in 10 years at age 65.

To obtain a sense of the potential outcomes, both on the downside and upside, Table 2 and Figure 1 show the costs for retirement at the 90th percentile of the distribution on the horizontal axis. The median costs for retirement are shown on the vertical axis.

The 90th percentile reflects the downside risk of a strategy. These are cases when retirement becomes more expensive due to some combination of long life and/or poor market returns. The median reflects the more typical cost: half of the time retirement would cost more and half of the time it would cost less.

These costs reflect the amount of assets required today (at age 55) to fund the desired retirement starting at age 65, assuming the couple did not make any additional contributions to their savings in the future. Naturally, future savings would reduce the assets required at present, but future savings would not change the relative positions of the efficient frontiers in terms of

understanding the role of partial annuitization. Non-annuitized assets held today would have 10 years to grow (or shrink, depending on realized market returns) as a lump-sum investment before withdrawals begin at age 65.

Figure 1 shows frontiers for clients based on the different possible allocations between stocks and bonds, with and without the use of a DIA. The blue frontier shows stock/bond combinations without a DIA. The percentages identified in the figure are the stock allocations. These range from zero percent stocks in the upper right part of the figure to 100 percent stocks at the lowest part of the figure (these numbers are also listed in the first columns of Table 2). Remember, the client’s objective was to minimize retirement costs. This means that more efficient strategies would move them toward the lower left-hand part of the figure. Downward and leftward movements reduce both median retirement costs, as well as worst-case retirement costs.

The zero percent stock allocation, for instance, leads to a median retirement cost (the cost of funding a real $100,000 per year in today’s dollars starting at age 65) of just over $2 million. Retirement would cost $3.38 million for those in the unlucky 90th percentile. On the downside, the 90th percentile retirement cost with an investment-only approach would be minimized at 70 percent stocks, with a retirement cost of $2.3 million. With this allocation, the median retirement cost (the amount needed today) was $1.1 million. Meanwhile, 100 percent stocks minimized the median retirement cost (as the equity risk premium can be adequately relied upon at the median) at $965,000, but it did create greater downside risks with a 90th percentile retirement cost of $2.4 million.

Figure 1 also shows outcomes with partial annuitization, shown as the red frontier. Partial annuitization consists of different asset allocation combinations along with an immediate purchase of a DIA that begins income at age 65. This purchase represents a dollar amount equal to half of the fixed income allocation, up to $500,000, assuming the individual has accumulated the median amount necessary by age 55 to fund their retirement goal.

Dashed lines between the blue frontier and the red frontier indicate points with the same overall initial allocation to stocks from a total wealth perspective in the median case after part of the financial portfolio was used to purchase the DIA. These allocations are also provided in Table 2.

A Better Comparison

For this analysis, we assumed that someone who purchases a DIA considers their premium as part of their fixed-income allocation, so that their remaining financial portfolio will have a more aggressive stock allocation. For instance, someone with a 30/70 allocation to stocks and bonds, without partial annuitization cannot properly be compared to someone who places a large sum into a DIA contract and subsequently maintains a 30/70 allocation with their remaining financial assets. From a household balance sheet perspective, this individual would have a much higher total allocation to fixed income, because the DIA can be viewed as essentially a bond portfolio held within an annuity wrapper. Alternatively, it is possible to consider the dollar amount invested in stocks will fall dramatically if the same stock allocation is maintained after partial annuitization. A proper comparison of portfolios requires that the individuals have the same dollar amount in stocks, regardless of their decision about partial annuitization.

To create a better comparison, we assumed that for each stock/bond allocation for the no-annuity case, the couple currently held the median amount of wealth required for a successful retirement. We adjusted the stock allocation so the dollar amount held in stocks stayed the same after purchasing a DIA. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 2, partial annuitization improved outcomes when the dashed red line moved from the blue curve to the red curve in a direction toward the bottom left-hand corner of the chart. This implies lower average and downside costs for retirement with partial annuitization.

A couple willing to hold up to 70 percent stocks will clearly benefit from partial annuitization as costs are lowered both at the median and at the extreme. Couples willing to hold more than 70 percent stocks will still reduce median costs with partial annuitization, although downside costs rise. The increase in downside costs is not a result of the DIA, but rather because in these scenarios not enough was shifted to the DIA and the overall stock holdings increased with the higher stock allocation. This is a side effect of planning the DIA purchase based on median wealth requirements.

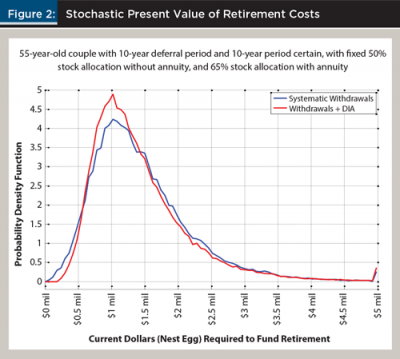

Figure 2 shows an efficient frontier using two points from the distribution of outcomes (the median and 90th percentiles of retirement costs). It is worthwhile to consider the entire distribution of retirement costs. The distributions are illustrated for the case of holding a 50 percent stock allocation without the use of a DIA, and for the case of maintaining a 65 percent stock allocation with remaining financial assets after devoting $324,000 (half of the median allocation to fixed income) to the DIA.

These distributions are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3. Figure 2 provides the probability density function, which shows the distribution of possible retirement costs. The DIA helps to narrow the distribution of outcomes with fewer very low-cost retirements, but also fewer high-cost retirements.

Figure 2 is helpful to see the full range, but it is perhaps best to provide further analysis with the cumulative distribution function shown in Figure 3. This figure shows the probability that retirement will cost less than the numbers shown on the horizontal axis. For instance, with the investment-only strategy, there is a 29.8 percent chance that retirement will cost less than $1 million. There is a 31.1 percent chance that retirement will be less than $1 million when partially annuitizing.

Although non-annuitization provides a better chance for success at lower wealth levels (less than about $800,000), the probability of success is so low in such cases that most clients working with financial planners would be unsatisfied and would seek to improve the performance of their plan by working longer, saving more, or planning to spend less in retirement. For wealth levels with any reasonable chance for success, partial annuitization improves odds for the couple relative to an investment-only strategy. For individuals who have been saving sufficiently for their retirement, partial annuitization using DIAs helps to improve outcomes.

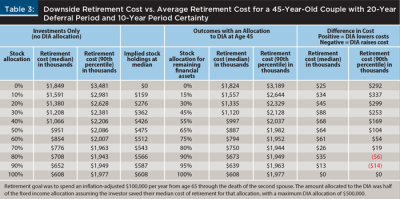

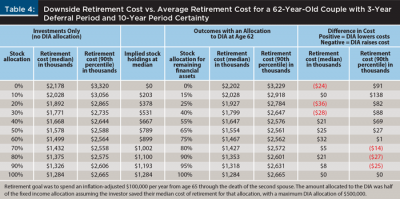

Results for Other Cases

Although the basic story remains the same for 45-year-old and 62-year-old couples, the results for these cases highlight some age-related trends for retirement costs and partial annuitization. Results are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Generally, being younger allows more time for assets to grow before withdrawals begin. This explains why older couples require more assets at the present in order to fund their retirement-spending goals. Nonetheless, the general conclusions found with the 55-year-old baseline case—that the use of DIAs as a fixed-income substitute reduce the median cost and risk of a retirement portfolio up to about a 70 percent equity allocation—are also seen with the other cases as well. Benefits are most clear for the age 45 scenario.

Conclusions

Income annuities with short deferral periods provide a future guaranteed retirement income stream. A conventional DIA will pay a specified amount in the future; that amount is a function of today’s bond returns and expected mortality rates when the DIA payment begins.

A short deferral DIA can be a valuable complement to a conventional portfolio withdrawal strategy. Similar to the benefit of allocating bonds to single premium immediate annuities as illustrated in Pfau (2013), this analysis shows that a short deferral DIA that provides lifetime income can lower the cost of funding retirement by softening the financial blow of a long lifetime or poor market returns.

The primary contribution of this paper is to show how the pre-purchase of an income annuity can provide similar improvements in efficiency. Simulations in which we varied asset returns and the length of time in retirement provide evidence that partial annuitization can reduce costs in worst-case retirements and in average retirements. The tradeoff is lower wealth for retirees who do not live as long; however, this loss is reduced by the return of premium if the client dies before income begins and the 10-year period certain feature.

Financial planners creating a retirement income strategy can reduce the expected costs of funding a retirement income by allocating a portion of their client’s investments to a DIA, particularly if the retiree is worried about investment risk in the near term or running out of money later in life.

Investors may wish to purchase a DIA for two primary reasons. The first is to lock in retirement income prior to retirement in order to avoid the possibility that a poor sequence of asset returns will jeopardize retirement income sustainability. A pre-retirement DIA purchase can also provide a psychological benefit to a client who is able to take current gains off the table and buy an income that will last a lifetime. The simulations show that the pre-retirement purchase of a DIA can significantly reduce the likelihood of negative outcomes that can endanger a client’s ability to maintain a desired spending goal.

The second reason to purchase a DIA is to protect against the risk of running out of money in old age. Although it is not considered in detail in this paper, a DIA with a longer post-retirement deferral period can be seen as an insurance product that pays out a significant income per dollar invested later in retirement when a client is most at risk of outliving assets. The use of a DIA for longevity protection may also be an important psychological tool that reduces the anxiety of short-run portfolio volatility by ensuring that the client will never bear substantial lifestyle risk later in life.

DIAs are more attractive when clients are risk averse and would otherwise prefer a portfolio with a low stock allocation. Shifting assets from a low-risk portfolio to a DIA involves fewer tradeoffs when the client would have otherwise invested in similar safe assets. Shifting bonds into a DIA will always provide a bonus, because the client receives a bond-like return with the added longevity protection of annuity.

Because a partial annuitization DIA strategy shifts a percentage of the portfolio into a bond-like investment, the percentage stock allocation in the rest of the portfolio will need to be increased to match the level of portfolio risk that would exist in a non-annuitized portfolio. For clients who may be unwilling to accept an increase in stock holdings within an investment portfolio, a smaller DIA purchase with a longer deferral period may be a more appropriate way to buy long-life income protection.

A risk of DIAs present in a portfolio of longer-duration bonds is the possibility that rising interest rates and inflation will erode the purchasing power of future income payments. An innovative variation on the traditional DIA are products whose investment component is allowed to vary over time with market returns. These new products offer the potential for payouts to increase over time, while payouts from a traditional, fixed DIA will be based on interest rates in effect when it is purchased. Financial planners can look forward to continued innovation in DIA products that are able to hedge longevity and inflation risks more efficiently.

References

Milevsky, Moshe A. 2006. The Calculus of Retirement Income. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pfau, Wade D. 2011. “Safe Savings Rates: A New Approach to Retirement Planning over the Lifecycle.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (5): 42–50.

Pfau, Wade D. 2013. “A Broader Framework for Determining an Efficient Frontier for Retirement Income.” Journal of Financial Planning 26 (2): 48–55.

Pfau, Wade D. 2014. “The Lifetime Sequence of Returns: A Retirement Planning Conundrum.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 68 (1): 53–58.

Citation

Finke, Michael, and Wade Pfau. 2015. “Reduce Retirement Costs with Deferred Income Annuities Purchased before Retirement.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (7): 40–49.