Journal of Financial Planning: July 2016

Jing Jian Xiao, Ph.D., is a professor of consumer finance in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of Rhode Island. He has published many research papers in consumer finance journals and books including Handbook of Consumer Finance Research and Consumer Economic Wellbeing. He received his Ph.D. in consumer economics from Oregon State University.

Nilton Porto, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of consumer finance in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of Rhode Island. He received his Ph.D. in consumer science from the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Acknowledgments: Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the FPA Annual Conference—BE Boston 2015, and at the Academy of Financial Services 2015 Annual Meeting, in which session participants provided helpful suggestions. Three anonymous reviewers and two editors also provided helpful suggestions for further improving the paper. Those suggestions were incorporated into this version.

Executive Summary

- Financial satisfaction is an indicator of consumer financial well-being that is an important component of overall life satisfaction. The purpose of this study was to examine the association between financial advice topics and financial satisfaction.

- This study used data from the 2012 National Financial Capability Study, which asked more than 25,000 respondents nationwide whether they received financial advice from any financial service professional in the last five years. Results of t-tests showed that respondents who received financial advice on all financial topics except debt counseling, compared to those who did not receive advice, scored higher on financial satisfaction.

- Multiple regression analysis findings indicated that, controlling for several demographic and financial variables, advice on investments and taxes was positively associated with financial satisfaction. Debt counseling, mortgage/loan, and insurance advice were initially negatively associated with financial satisfaction. However, when these topics were paired with investment or tax advice, the negative associations with financial satisfaction disappeared or were changed to positive.

- Financial planners may consider combining topics that may have potentially negative connotations with advice on investments and taxes to generate client satisfaction or reduce client dissatisfaction.

In the 2015 presidential address of the American Finance Association, Luigi Zingales (Zingales 2015) discussed the social utility of finance and called for financial researchers to document the benefits of the financial industry. A study on financial advice was recently cited as being among the positive contributions for society (Von Gaudecker 2015). The research literature on the benefits of financial advice is emerging.

Research has shown that financial advice may help clients reduce wealth volatility (Grable and Chatterjee 2014) and improve investment returns (Von Gaudecker 2015). The benefits of financial advice have also been discussed in theoretical analyses, such as Hanna and Lindamood (2010) and in empirical surveys, such as Warschauer and Sciglimpaglia (2012). However, no previous research is found to examine potential effects of financial advice topics on financial satisfaction. This study attempted to fill this gap by examining the association between financial advice topics and financial satisfaction, to provide general implications for financial planners.

Understanding Financial Satisfaction and the Dataset

Financial satisfaction is a subjective measure of financial well-being. It is an important component of life satisfaction (Xiao, Tang, and Shim 2009). And it is associated with income (Hsieh 2004; Grable, Cupples, Fernatt, and Anderson 2013), assets (Hansen, Slagsvold, and Moum 2008), and financial capability (Xiao, Chen, and Chen 2014).

In the research literature of financial advice, financial satisfaction is used as one of the demand factors (for example, Robb, Babiarz, and Woodyard 2012). In this study, financial satisfaction is treated as the dependent variable.

Using a large-scale, national dataset, this study examined whether financial advice topics are associated with financial satisfaction. The 2012 National Financial Capability Study, which surveyed more than 25,000 respondents nationwide, was the dataset used. The survey asked respondents if they have asked for any advice from a financial professional in the last five years on any of the following topics: debt counseling, savings or investments, taking out a mortgage or loan, insurance of any type, and tax planning.

Note that survey respondents were asked whether they received financial advice from any financial professionals. Among the five topics, saving and investing, insurance, and tax planning may be most pertinent to financial planning, while debt counseling and mortgage and loan may be less relevant. For the purpose of comparison, all five topics were included in this study. Additional information about the dataset is presented later.

The results are an indication of which financial topics are associated with financial satisfaction. Financial planners can use this information to better understand client behavior that may increase client retention and the likelihood of clients following their advice.

Three Areas of Prior Research

Consumer demand for advice. Research on financial advice can be categorized into three lines. One line of the literature examined factors associated with consumer demand for financial advice. Hanna (2011) used data from 1998–2007 Surveys of Consumer Finances to investigate demand factors for financial planning advice and found that the likelihood of using a financial planner was strongly related to risk tolerance; those with low risk tolerance were the least likely to use a financial planner, those with above-average risk tolerance were the most likely to use a financial planner, while those with substantial risk tolerance had a significantly lower likelihood of using a financial planner than those with above-average risk tolerance. Black households were more likely to use a financial planner, but Hispanic and other/Asian households were less likely than comparable white households to use a financial planner.

Finke, Huston, and Winchester (2011) examined characteristics of consumers who purchased financial advice and found that respondents who paid for financial advice were more likely to be female, relatively older, wealthier, and college educated, but did not have a high level of financial knowledge. In addition, among purchasers of financial advice, those who bought comprehensively managed services were more likely to be under age 65, wealthy, and have a high level of financial knowledge.

Some research has focused specifically on the determinant of trust. Agnew et al. (2014) conducted experimental research to examine how financial advice clients form opinions of adviser quality. They found that a simple and easily replicated confirmation strategy could help form client opinion. For example, study participants were likely to rate advisers who gave good advice on the first easy topic, followed by bad advice on two ambiguous topics, as being just as trustworthy, competent, and professional as advisers who gave good advice on all topics. They also showed that consumers used external signals such as professional credentials to guide their choices when the quality of advice was unclear.

Lachance and Tang (2012) used the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) data to examine associations between trust and financial advice-seeking. They found that trust and cost were the two most important determinants of financial advice-seeking behavior. Saving/investment advice was the most affected with use increasing from 17 percent for the least trusting group, to 44 percent for the most trusting group.

Researchers have also examined potential effects of financial literacy and capability on financial advice-seeking. Bucher-Koenen and Koenen (2010) conducted a theoretical analysis suggesting that higher signals of consumer information should indeed lead advisers to provide better services. With panel data from Germany, they showed that individuals with higher financial literacy were more likely to solicit financial advice, but less likely to follow it.

Robb, Babiarz, and Woodyard (2012) used the NFCS data and found that financial knowledge—measured by both objective and subjective indicators—was positively associated with investing, insurance, and tax planning advice. In this study, financial satisfaction was used as one of the predicting variables that was also associated with these financial planning advice-seeking variables. Porto and Xiao (forthcoming) used the NFCS data and found that consumers who were overconfident in financial literacy were more likely to use financial advice on tax planning and less likely to do so on investment planning.

Calcagno and Monticone (2015) examined the association between consumer financial literacy and demand for financial advice and found that non-independent advisers (those who provide advice and sell financial assets at the same time) were not sufficient to alleviate the problem of low financial literacy. The investors with a low level of financial literacy were less likely to consult an adviser, but they delegated their portfolio choices more often or did not invest in risky assets at all. The advisers provided more information to knowledgeable investors who, anticipating this, were more likely to consult them.

Debbich (2015) conducted both theoretical and empirical analyses with French data and found that financial literacy was strongly associated with the probability to consult with a financial adviser. After decomposing the measure of financial literacy, he found that the relationship was weakly monotonic, which provides support to the fact that financial advice cannot substitute for financial literacy, which is consistent with Collins (2012).

Researchers have also examined neighborhood access to financial advice-seeking. Chong, Phillips, and Phillips (2011) used ZIP code level data from the U.S. to explore the relationship between the ethnic composition of a ZIP code and the types of financial planning professionals offering services there and found that significant differences exist among them.

Demand among special populations. Another line of research explored financial demand of special populations, such as the elderly and low-income consumers. Using data from the Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) dataset, Cummings and James (2014) examined factors related to seeking and dropping financial advisers among older adults. They found that getting a financial adviser was positively associated with becoming a widow(er), asking family members for assistance with financial decisions, seeking professional help for emotional problems, and experiencing increases in income and net worth. Dropping a financial adviser was negatively associated with becoming a new widow(er), getting married, and experiencing an increase in net worth.

Tang and Lachance (2012) used the NFCS data and examined factors associated with financial advice demand among low-income consumers. They found that these consumers used less investment advice than insurance advice, and when they made decisions to seek advice, cost played a lesser role.

Effects of financial planning advice. The third line of research has documented potential effects of financial planning advice. Direr and Visser (2013) examined an association between financial adviser characteristics and client portfolio choices. They used a large administrative dataset in France and found that the share invested in risky funds was larger when the adviser was more educated. Furthermore, male advisers sold larger shares of risky funds than female advisers.

Foerster, Linnainmaa, Melzer, and Previtero (2014) examined potential effects of financial advice using data from Canada. They found that advisers induced their clients to take more risk, thereby raising clients’ expected investment returns. On the other hand, they noticed that advisers directed clients into similar portfolios independent of their clients’ risk preferences and stage in the life cycle. This one-size-fits-all advice may be costly. They estimated that the value-weighted client portfolio lagged passive benchmarks by more than 2.5 percent per year net of fees.

Several studies have documented the benefits of financial planning advice. Hanna and Lindamood (2010) conducted theoretical analyses to quantify economic benefits for personal financial planning and concluded that the value of advice varies with the client’s risk aversion and the percentage of wealth that could be gained or lost. They recommended that the most risk averse households should place highest value on comprehensive financial planning advice.

Warschauer and Sciglimpaglia (2012) conducted an online survey among consumers to examine the economic benefits of financial planning and found that various financial planning services were valued by consumers differently, and these services were valued by various consumer groups differently. For example, services regarding emergency funds, legal documents about trusts, and health insurance were listed as top-valued services. Consumers with high investment assets scored higher on values of services on emergency funds than those with low investment assets.

Grable and Chatterjee (2014) created a measure of wealth volatility, zeta, and found that financial planning service reduced client wealth volatility. Using Dutch data, Von Gaudecker (2015) demonstrated that nearly all consumers who scored high on financial literacy tests or relied on professionals or private contacts for advice achieved reasonable investment outcomes. Compared to these groups, consumers with below-median financial literacy who trusted their own decision-making capabilities lost an expected 50 basis points on average.

Method

Hypothesis. This study contributed to the line of research on the benefits of financial advice and attempted to examine the link between financial advice topics and financial satisfaction. In this study, the following hypothesis was tested: receiving financial advice on any topic increases financial satisfaction.

Data. Data used in this study were from the 2012 National Financial Capability Study. In consultation with the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the President’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy, the FINRA Investor Education Foundation commissioned the survey that included 25,509 American adults (roughly 500 per state, plus the District of Columbia and 1,000 military service members) through online surveys (FINRA Investor Education Foundation 2013). The dataset is available for public use from the website of the FINRA Investor Education Foundation, www.FINRAfoundation.org. For this study, observations were removed for respondents who reported “don’t know” or “prefer not to say” for the financial satisfaction question, which resulted in a sample size of 24,951 observations.

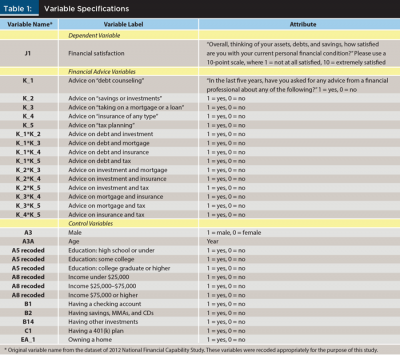

Variables. The dependent variable was financial satisfaction, which was measured by a 10-point Likert-type scale. There were two sets of independent variables. One set included financial advice topic variables that were dummy variables on if receiving financial advice on debt counseling, savings/investing, mortgage or loan, insurance, and tax planning. Ten dummy variables indicating receiving financial advice on any combination of two topics were also included. Another set of independent variables included selected demographic and financial condition variables that have been shown to correlate with financial satisfaction in previous research. The demographic variables included gender, age, and education. The financial condition variables included income, homeownership, and several asset holding variables (having a checking account, CDs/savings/money market accounts, investments, and 401(k) plans). Variable specifications including the original wording of several survey questions are presented in Table 1.

Analyses. As preliminary analyses, a series of t-tests were conducted to examine if there were differences between users and non-users of financial planning services. Three multiple regression analyses were conducted with financial satisfaction as the dependent variable. In model 1, only financial condition variables were included as independent variables, which served as the baseline model. In model 2, individual financial advice variables were added as independent variables to examine unique contributions of these variables. In model 3, variables of a combination of any two topics were entered. As further analyses, a series of additional multiple regressions were conducted, in which one single or dual-topic variable was entered into the model at each time for all financial advice topic variables.

Results

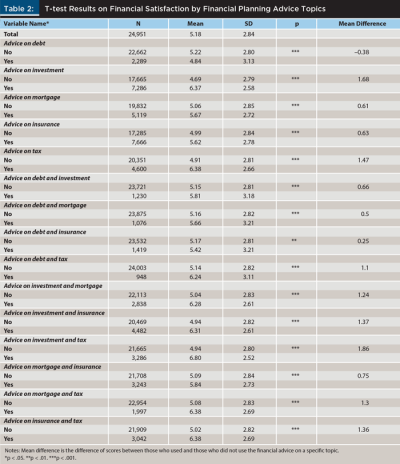

Table 2 presents results of the t-tests. The results show that consumers who received advice on any single topic, except for debt counseling, scored higher on financial satisfaction than those who did not. For example, consumers who reported using investment advice scored 6.37 in financial satisfaction compared to consumers who did not use investment advice with a financial satisfaction score of 4.69 (p<.001). Among the four individual topic variables showing higher scores among users, mean differences of investment advice and tax advice between users and non-users were the highest, 1.68 and 1.47, respectively.

Also, consumers who reported receiving advice on any combinations of two topics scored higher in financial satisfaction. For instance, consumers who received both investment and insurance advice scored 6.31 in financial satisfaction, compared to those who did not use these services, who scored 4.94 (p<.001). Interestingly, respondents who used advice in all combinations between debt counseling and any other topic also reported higher scores in financial satisfaction than those who did not use the services. The highest mean difference was the combination between investment and tax, which was 1.86.

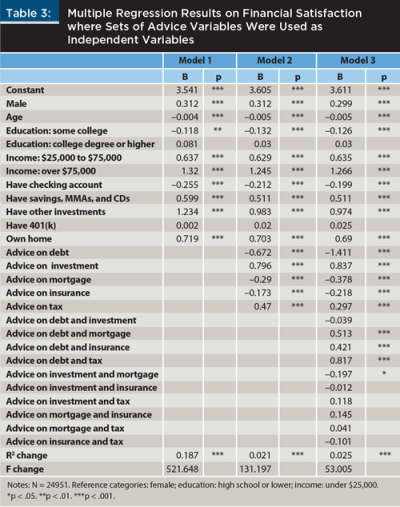

Table 3 presents the main regression results. The purpose of these analyses was to show unique contributions of financial advice topics to financial satisfaction. Model 1 was the baseline model and the results were consistent with previous research. In model 2, five financial advice topic variables were added. Comparing the R2 change between model 1 and 2; R2 increased 0.021, suggesting these topic variables explained an additional 2.1 percent of variations of financial satisfaction. Among these variables, advice on investment and tax were positively associated with financial satisfaction, and advice on debt counseling, mortgage, and insurance were negatively associated with financial satisfaction.

In model 3, 10 dummy variables indicating any combination of any two topics were added to the model. The R2 change from model 1 to model 3 was 0.025, suggesting the 2.5 percent additional variances were explained by all single- and dual-topic variables. The signs of the five individual topic variables were unchanged. Among 10 variables indicating combinations between any two topics, three showed positive associations and one showed a negative association.

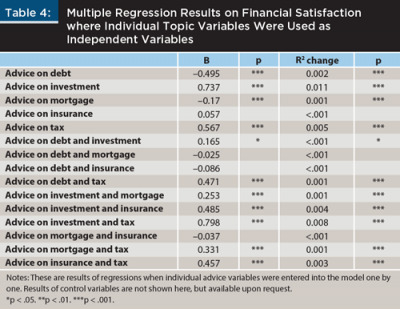

To get more insight on potential effects of advice topic variables, a series of multiple regressions on financial satisfaction were conducted where only one topic variable was included in the model each time. Table 4 presents the results. Topics on investment and tax were still positively associated with financial satisfaction, and topics on debt counseling and mortgage were still negatively associated with financial satisfaction. Insurance advice was not significantly associated with financial satisfaction in this model. Also, among variables of combined topics, any topics combined with investment and tax showed positive associations with financial satisfaction.

Discussion

Using a large-scale national dataset, this study examined potential effects of financial advice topics on financial satisfaction among consumers.

Before the results are discussed and interpreted, limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. First, only cross-sectional data, which can only demonstrate associations between variables, was used. Discussion about the results and implications should be interpreted as inconclusive about the causality. Second, the survey was conducted among a national sample of people who reported if they received financial advice from any financial service professionals. We do not know what types of financial professional the respondents received advice from, which could be financial planners, counselors, coaches, or other advisers. Thus, we only document the associations between financial advice topics and financial satisfaction. More information on the source of advice would strengthen this line of research in the future.

The results of this study suggest that investment advice and tax advice may increase consumer financial satisfaction. Financial advice on investment and tax planning shows positive associations with financial satisfaction when they are used as both individual topic variables and dual-topic variables. The findings suggest that financial advice on investments and taxes may contribute to consumer financial well-being measured by financial satisfaction, another piece of evidence showing the benefits of financial advice and consistent with previous research (Grable and Chatterjee 2014; Hanna and Lindamood 2010; Warschauer and Sciglimpaglia 2012).

Negative associations between two debt-related variables and financial satisfaction were found in this study, which was against the hypothesis. It was assumed that financial satisfaction as a measure may have two components: self-perceived financial status, and self-perceived other psychological states such as hopes, desires, and emotions. One possible reason for the negative association is that even after controlling for financial condition variables such as income and assets, financial satisfaction was still a partial measure of financial status, and people who seek advice on debt counseling and mortgages and loans had a lower level of financial position compared to those who do not seek debt-related advice. Another explanation may be that through financial counseling and advising, they found their financial positions were worse than they expected, thus reducing their financial satisfaction. Future research may explore the validity of these speculations.

The study also found a negative association or no association between insurance and financial satisfaction (see Tables 3 and 4). Insurance advice may mean many different things. One might seek life insurance advice after a recent death in the family, while other respondents might answer this question of whether they received insurance advice while thinking of auto insurance they recently purchased (a sales transaction) or an insurance claim they had to recently file (often not a pleasant situation); both of which may be imbued with negative connotations.

To shed some light on this finding, the correlation of insurance advice and ownership of life insurance was calculated, and the correlation was weak and negative (Pearson correlation was –0.16). This might indicate that respondents were not thinking of life insurance or long-term care insurance when answering this question. Future research is needed to further clarify this issue.

Although three single-topic variables were negatively associated with financial satisfaction, when combined with other topics such as investment and tax, most negative associations became insignificant or changed to positive ones, which is consistent with some business practices. For example, many insurance agents combine insurance products with investment products. Future research is needed to explore the mechanism of the negative associations between certain types of financial advice and financial satisfaction and to develop strategies to improve customer satisfaction.

Implications for Financial Planners

The results of this study have implications for financial planners who provide needed services for consumers. Among five financial advice topics, three are particularly pertinent to financial planning: saving and investing, insurance, and tax planning. Results of this study indicate that consumers receiving investment advice or tax advice, or any combinations that include investment and tax, tend to have higher scores in financial satisfaction. Because of the data limitations, we cannot infer causality, but the results may imply possible positive effects of the two topics on financial satisfaction. Financial planners might increase customer satisfaction when emphasizing their discussions related to these topics.

The study results also showed that insurance advice was negatively associated with financial satisfaction. More research needs to be done to explore possible reasons. For financial planners, however, this finding at least tells them that when the topic of insurance is discussed, they may wish to be sensitive to the potential negative connotation associated with it. A possible strategy to minimize this undesirable association between insurance and financial satisfaction can be borrowed from the concept of framing effects (Thaler 1985; Tversky and Kahneman 1981) by discussing insurance along with topics like taxes or investments, in which framing the discussion as an asset preservation conversation might be perceived more favorably than framing it as a conversation about mortality and protecting against loss.

Research findings of this study also suggest that combining insurance with investment or tax planning may increase client financial satisfaction compared to discussing insurance as a sole topic.

References

Agnew, Julie R., Hazel Bateman, Christine Eckert, Fedor Iskhakov, Jordan J. Louviere, and Susan Thorp. 2014. “Individual Judgment and Trust Formation: An Experimental Investigation of Online Financial Advice.” ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research white paper, available online at www.cepar.edu.au/media/136403/bateman_2014.02.pdf.

Bucher-Koenen, Tabea, and Johannes Koenen. 2010. “Do Smarter Consumers Get Better Advice? An Analytical Framework and Evidence from German Private Pensions.” Collegio Carlo Alberto discussion paper, available online at www.carloalberto.org/assets/events/2012-cerp-conference/bucherkoenenpaper.pdf.

Calcagno, Riccardo, and Chiara Monticone. 2015. “Financial Literacy and the Demand for Financial Advice.” Journal of Banking & Finance 50: 363–380.

Chong, James, Lynn Phillips, and Michael Phillips. 2011. “The Impact of Neighborhood Ethnic Composition on Availability of Financial Planning Services.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 65 (6): 71–83.

Collins, J. Michael. 2012. “Financial Advice: A Substitute for Financial Literacy?” Financial Services Review 21 (4): 307–322.

Cummings, Benjamin F., and Russell N. James III. 2014. “Factors Associated with Getting and Dropping Financial Advisers among Older Adults: Evidence from Longitudinal Data.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 25 (2): 129–147.

Debbich, Majdi. 2015. “Why Financial Advice Cannot Substitute for Financial Literacy?” Banque de France Working Paper No. 534 available online at www.banque-france.fr/uploads/tx_bdfdocumentstravail/DT-534.pdf.

Direr, Alexis, and Michael Visser. 2013. “Portfolio Choice and Financial Advice.” Finance 34 (2): 35–64.

Finke, Michael S., Sandra J. Huston, and Danielle D. Winchester. 2011. “Financial Advice: Who Pays.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 22 (1): 18–26.

FINRA Investor Education Foundation. 2013. “Financial Capability in the United States: Report of Findings from the 2012 National Financial Capability Study.” Available online at www.usfinancialcapability.org/downloads/NFCS_2012_Report_Natl_Findings.pdf.

Foerster, Stephen, Juhani T. Linnainmaa, Brian T. Melzer, and Alessandro Previtero. 2014. “Retail Financial Advice: Does One Size Fit All?” National Bureau of Economic Research working paper No. 20712.

Grable, John E., and Swarn Chatterjee. 2014. “Reducing Wealth Volatility: The Value of Financial Advice as Measured by Zeta.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (8): 45–51.

Grable, John E., Sam Cupples, Fred Fernatt, and NaRita Anderson. 2013. “Evaluating the Link between Perceived Income Adequacy and Financial Satisfaction: A Resource Deficit Hypothesis Approach.” Social Indicators Research 114 (3): 1,109–1,124.

Hanna, Sherman. D. 2011. “The Demand for Financial Planning Services.” Journal of Personal Finance 10 (1): 36–62.

Hanna, Sherman D., and Suzanne Lindamood. 2010. “Quantifying the Economic Benefits of Personal Financial Planning.” Financial Services Review 19 (2): 111–127.

Hansen, Thomas, Britt Slagsvold, and Torbjørn Moum. 2008. “Financial Satisfaction in Old Age: A Satisfaction Paradox or a Result of Accumulated Wealth?” Social Indicators Research 89 (2): 323–347.

Hsieh, Chang-Ming. 2004. “Income and Financial Satisfaction among Older Adults in the United States.” Social Indicators Research 66 (3): 249–266.

Lachance, Marie-Eve, and Ning Tang. 2012. “Financial Advice and Trust.” Financial Services Review 21 (3): 209–226.

Porto, Nilton, and Jing Jian Xiao. (forthcoming). “Financial Literacy Overconfidence and Financial Advice Usage.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals.

Robb, Cliff A., Patryk Babiarz, and Ann Woodyard. 2012. “The Demand for Financial Professionals’ Advice: The Role of Financial Knowledge, Satisfaction, and Confidence.” Financial Services Review 21 (4): 291–305.

Tang, Ning, and Marie-Eve Lachance. 2012. “Financial Advice: What about Low-Income Consumers?” Journal of Personal Finance 11 (2): 121–158.

Thaler, Richard H. 1985. “Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice.” Marketing Science 27 (1): 15–25.

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1981. “The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice.” Science 211 (4481): 453–458.

Von Gaudecker, Hans-Martin. 2015. “How Does Household Portfolio Diversification Vary with Financial Literacy and Financial Advice?” The Journal of Finance 70 (2): 489–507.

Warschauer, Thomas, and Donald Sciglimpaglia. 2012. “The Economic Benefits of Personal Financial Planning: An Empirical Analysis.” Financial Services Review 21 (3): 195–208.

Xiao, Jing Jian, Chuanyi Tang, and Soyeon Shim. 2009. “Acting for Happiness: Financial Behavior and Life Satisfaction of College Students.” Social Indicators Research 92 (1): 53–68.

Xiao, Jing Jian, Cheng Chen, and Fuzhong Chen. 2014. “Consumer Financial Capability and Financial Satisfaction.” Social Indicators Research 118 (1): 415–432.

Zingales, Luigi. 2015. “Presidential Address: Does Finance Benefit Society?” The Journal of Finance 70 (4): 1,327–1,363.

Citation

Xiao, Jing Jian, and Nilton Porto. 2016. “Which Financial Advice Topics Are Positively Associated with Financial Satisfaction?” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (7): 52–60.