Journal of Financial Planning: March 2016

Trevor R. Chuna, CFP®, AEP®, CTFA, is managing director at Sequoia Financial Group where he works with planners on technical details, including the modeling, forecasting, and analysis of financial and estate plans.

An irrevocable trust established during life or at death as part of an estate plan represents a primary vehicle used to transfer and manage assets to meet the objectives and dispositive goals of the grantor and the beneficiaries—at the time the trust is created. However, goals and objectives can change quickly with the changing circumstances of the grantor and the beneficiaries. And irrevocable trusts, by their very nature, do not change—at least that’s what we tend to think.

As financial planners, we set plans in motion based on client-communicated wishes and our understanding of what the future may hold. But we can’t see into a crystal ball that shows us all the circumstances and events around which we should be planning. Consider the following examples:

- Changes in tax law over recent years have allowed a married couple with a previously taxable net worth of $3 million to now pass tax free. Why do they need that old ILIT with $1 million of coverage?

- The trust, originally funded by dad, has made distributions to the point that the current level of assets no longer justifies the cost of administration.

- The beneficiary of a trust who, along with his spouse, is dependent on distributions; except, upon the beneficiary’s death, the trust forces distribution to the kids, and the spouse is inadvertently left without a source of income.

Modification Options

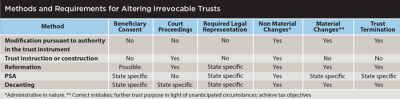

Contrary to popular belief, when life’s circumstances change, there are ways to change the impacted irrevocable trust.

Private settlement agreement. Trusts that are no longer needed or economically viable to maintain given the size, may contain specific provisions that allow an independent trustee or trust protector (sometimes referred to as a “trust adviser”) specific powers in the trust instrument itself to modify provisions or terminate the trust altogether and distribute it outright. If specific language of this nature is not present, a private settlement agreement can modify administrative trust provisions, effective from the date of the modification moving forward. These changes generally cannot be used to terminate the trust or change beneficial interests, although some states may allow for such material changes depending on the parties to the agreement. Individuals with a beneficial interest may require legal representation as part of the agreement or otherwise receive notification of the court proceeding.

Decanting. If trust language or a private settlement agreement falls short, as the case may be when trying to avoid impoverishment of a beneficiary’s spouse, decanting may provide a solution. Decanting allows a trustee to distribute trust assets from an old trust to a new one that has different terms, generally without court or beneficiary approval. This leaves behind the unwanted sentiment or provisions that don’t meet the client’s needs and allows for new ones, such as the ability to name a beneficiary’s spouse as a potential beneficiary of the trust through a limited power of appointment. Common goals associated with decanting include the incorporation of more modern administrative provisions such as the use of a trust adviser, changing the trustee or the trustee succession provisions, and allowing the trustee the ability to change the situs of the trust. Approximately 23 states have enacted decanting statutes, and all of them differ to some degree regarding the required provisions of the old trust versus the new trust.

If the trust is not wholly discretionary, meaning the trustee has limiting standards when making distributions, then some common requirements must be considered for decanting to be a viable option:

The trustee must have the power to invade principal for trust beneficiaries. (If distributions are limited by an ascertainable standard, such as “health, education, maintenance, and support,” the trustee’s power is not sufficient to meet this requirement in some states or the decanting power is more narrow.)

Permissible beneficiaries of the new trust must include at least one of the beneficiaries of the old trust, and adding new beneficiaries is disallowed. (Some states allow the addition of a power of appointment exercisable by the beneficiary that can benefit someone else.)

Certain beneficiary rights, such as an income interest or right to withdraw assets at specified ages, cannot be eliminated in the new trust. (Although, they could potentially be modified from a required to discretionary distribution.)

If the trust is wholly discretionary, then the new trust would likely need to contain only one of the beneficiaries of the old trust. This potentially allows more liberal changes, such as the addition of new beneficiaries or all new trust terms.

If the trust document or state statute is unclear as to the trustee’s authority to take action or which action to take (as the case can be if a trust was not properly drafted), the trustee can petition the court of jurisdiction to provide administrative instruction or construction of the trust language.

Reformation. When clarification of the grantor’s intent is needed, trust reformation can be used to resolve unclear provisions or mistakes in the trust. To reform the trust, typically all individuals with a beneficial interest must have legal representation as part of the agreement or otherwise receive notification of the court proceeding. A reformation usually requires proof that the change is consistent with the grantor’s intent as of the original date the trust was executed. This can be hard to prove, especially if a new potential beneficiary is being added.

Uniform Trust Code

The methods for altering irrevocable trusts vary by state-specific law, which is frequently influenced by the Uniform Trust Code (UTC). The UTC is a proposal from a group of lawyers and academics in the trust field outlining what they believe each state’s trust law should look like. It can assist in interpreting trust law and may even be used by states that have not adopted the law for use in interpreting cases brought before the court. To date, the UTC has been enacted in some form in almost 30 states. The following are potential irrevocable trust modification options that may be available under the UTC.

Trust modification of nonmaterial terms. If the modification does not violate a material purpose of the trust, the interested parties could potentially enter into a binding, non-judicial settlement agreement. Examples of nonmaterial matters include interpretation or construction of the terms of the trust; approval of the trustee’s account reports; directing the trustee to refrain from performing a particular act or granting the trustee any necessary or desirable power; resignation or appointment of a trustee and determination of a trustee’s compensation; transfer of a trust’s principal place of administration; and the liability of a trustee for an action relating to the trust. If the settlement contains terms and conditions that a court could properly approve, such changes would have the same effect as if they were court approved. These agreements cannot be used to create a result not authorized by law.

Trust modification of material terms. This option typically requires court approval, which can generally be achieved with a modification that:

- has consent of the grantor and all the beneficiaries;

- has consent of all the beneficiaries (the most common way to modify an irrevocable non-charitable trust);

- does not have consent of all beneficiaries if the non-consenting beneficiaries’ interests will be protected (as long as there is no conflict of interest between the beneficiaries and their representatives as it relates to the item in question—another beneficiary or parent may represent and bind minors, unborn children, or incapacitated persons);

- furthers the purpose of the trust due to circumstances not anticipated by the grantor;

- corrects mistakes to conform to the grantor’s intention; or

- achieves tax objectives of the grantor that are not contrary to the grantor’s probable intention.

It may be possible to modify the trust without court approval in states that allow non-judicial settlement agreements.

Power to revoke or terminate. A trust may be terminated under the following circumstances: (1) according to the trust terms; (2) by the court if at creation there was a “mistake,” such as fraud or undue influence; (3) the trust achieved its purpose and all interested persons are represented before the court and consent to the termination; and (4) if the trust has assets below certain thresholds (varies by state), and it is no longer economical to continue the trust.

Other Considerations

Trust alterations generally cannot change the basic purpose of the trust; restrict a withdrawal right that is currently exercisable; change the trustee’s standards for making discretionary distributions; reduce a fixed income, unitrust, or annuity amount; eliminate state requirement for beneficiary information sharing; or add new beneficiaries, although it may be possible to grant a beneficiary powers of appointment to achieve a result as mentioned with the disinherited beneficiary’s spouse.

There are generally no income or estate tax consequences as it relates to the modification or reformation of the trust, as long as such changes are generally administrative in nature and the original trust is still in existence. Decanting differs in that the original trust no longer exists and has been appointed to a new trust (although some states do treat the new trust as an amendment to the existing trust). Currently, the IRS has not issued final Treasury Regulations that address the generation-skipping transfer tax (GSTT), gift tax, and estate tax consequences related to decanting. However, it is generally anticipated that GSTT-exempt status would be maintained if the decanting does not cause a shift of property to a lower generation for generation-skipping transfer purposes, and if the new trust does not extend the trust term beyond that of the original trust. There would generally be no gift tax consequences, although it may be argued that mandatory outright distribution provisions from the original trust that become discretionary may be considered a gift by the beneficiary back to the trust. There would generally be no estate tax consequences unless the new trust would provide a general (instead of limited) power of appointment to the beneficiary.

Additionally, there would generally be no direct income tax consequences caused by the actual modification event. There may, on the other hand, be future implications of the new trust provisions, such as a change in who is considered the owner of the assets for income tax purposes (for example, change “grantor” status) or a change in trustee provisions that have an effect on income and principal expense allocations or net investment income tax determination (the Medicare surtax). If a trust is decanted in full, it may be suggested that a final income tax return be filed for the old trust and a new tax ID be issued for the new trust.

Usually the decision to decant a trust is made by the trustee in his, her, or its absolute discretion, and he, she, or it is fully liable for the outcome even though the beneficiaries are typically making the request for the change. Formal beneficiary consent could limit this liability but may have undesirable tax consequences if they are agreeing to something that could change beneficial ownership, such as termination of an outright distribution.

Requirements for using each method discussed here are specific to state law and qualified legal counsel should be consulted as it relates to the specific circumstances of the case.

Circumstances change, feelings change, and it’s inevitable that laws and the tax code will change. With continued advancements in state trust law combined with sophisticated estate planners and attorneys alike, the irrevocable trust is becoming a more flexible estate planning tool and can be used to help your clients improve upon their original intentions. Being aware of the options and fully vetting them with a qualified estate attorney and tax adviser is key in the execution of such strategies and enhancing your client relationship.

This information is for educational purposes and does not constitute tax, legal, investment, or any other type of professional advice.