Journal of Financial Planning: March 2017

As a current financial planner and a former advertising executive, I understand and share in your frustration when it comes to the most basic building block of marketing—the value proposition. This key component serves as the starting point for every marketing activity, prospecting strategy, and client service activity. And yet, we see very few planners talk about their practice in a unique way. But, the few planners who do articulate their value find tremendous success.

Why do so few planners have this eureka moment, leaving the vast majority stuck peddling services that sound like the same services offered by so many other planners? The majority of planners I know tend to be logical and analytical. They like numbers and math. These are the crucial left-brain attributes needed to be a successful planner. Yet, to be a successful marketer requires a strong dose of right-brain attributes, especially creativity. This could explain why so many planners struggle to describe their value in a way in which the prospective client could relate.

This article proposes a new framework to develop a value proposition by taking a logical, analytical, left-brain approach to solving the problem. This new approach contrasts sharply with many other articles and books that use an approach geared toward planners who exhibit more right-brain attributes.

A New Framework

Financial planners do a poor job defining what makes them different from their competitors or the value they bring to a client. Too often planners define themselves using similar terms such as “holistic” and “comprehensive” or claiming to “help clients reach their financial goals.” This approach forces the potential client to determine what those phrases mean to them and their situation, which leaves the door open for misinterpretation as to what makes one planner different from another.

Why leave such an important issue in the hands of the client to decipher? Financial planners develop broad and generic descriptions of their businesses for many reasons. First, it’s complicated to develop and articulate the value. Second, the process can require a significant amount of time to complete. Third, there is a fear of getting it wrong and alienating existing clients. Fourth, planners have little experience in developing a value proposition that resonates with prospective clients. And fifth, for planners who look to hire consultants, it can be prohibitively expensive or may not yield the results the planner expected. If the planner can’t identify their value, it’s unlikely that a consulting firm could find insights that could move the needle. This intimidating process can leave planners befuddled and confused about how to proceed.

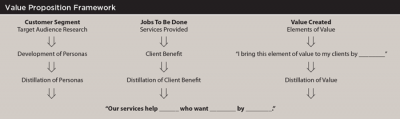

The new framework for developing a value proposition proposed here is built upon a simple ad-lib:

Our services help _______________ (customer segment) who want_______ (jobs to be done) by _______________ (value created).

This framework is based on one developed in the book Value Proposition Design (strategyzer.com/books/value-proposition-design) by Alex Osterwalder, Yves Pigneur, Greg Bernarda, and Alan Smith. The framework has been specifically adapted to work for financial planners. It outlines three components: customer segment, jobs to be done, and value created. The key to creating value lies in at least one of these three areas being completely unlike anything else offered by another financial planner. It’s important to reiterate that only one component must be truly unique; the other two can be more generic if the planner feels it necessary.

Customer Segment

The key factor in this framework places less emphasis on distilling intricacies within the existing client base. In an ideal situation, the planner may already serve a targeted market or realize they excel at helping a very specific audience. That alone could be a differentiating factor. Among planners, however, that situation tends to be the exception, not the rule. The reality is that most planners have a rather broad client base, and for a variety of reasons they do not want to restructure their practice to serve a niche audience.

Regardless of how broad a customer segment may be, it is important to go through the exercise of developing a description of the ideal customer segment. How to identify customer segments has been written about quite extensively. Some common methods include conducting client interviews, surveys, focus groups, and reviewing client notes. With data in hand, the planner can begin to sketch out a succinct paragraph that defines the target audience through descriptive demographic and psychographic information, or persona. It’s written to describe a real or imaginary client that can serve as the ideal client.

Here is an example: Jane and Joe are in their mid-50s. They live in the Hartford, Connecticut area and work for one of the major insurance companies. They hope to work for the next 15 years and need help saving for retirement. They feel overwhelmed with everything they need to do and are scared they haven’t saved enough for retirement. They lost confidence in the stock market after 2008.

For purposes of the ad-lib framework, the persona could be further distilled into one key element that succinctly captures that segment (or the segment the planner wants to target). Perhaps it’s “couples in their 50s”; “people who work in the insurance industry”; “people who have lost confidence in the market”; or a combination of those.

Jobs to Be Done

This component focuses on the services the planner will provide but with an important twist. For reasons similar to the ones mentioned earlier, many planners would rather cast a wide net and take the risk of sounding generic than take a risk of being known for doing a certain job or task better than anyone else and possibly lose clients who do not need that expertise. As a result, financial planners tend to default to “holistic financial planning” or “comprehensive financial planning.”

This approach has two problems. First, the phrases are confusing for the average client. As mentioned earlier, the client must interpret what the message means to him or her, and errors in translation may create a result not intended by the planner. Second, the phrases are internally focused. The statements describe what the planner does, not what the client needs. Instead, the planner should describe his or her services in terms the client will understand, such as:

- To make sure you can retire when you want;

- To help balance how you pay down your debts while saving for college and for retirement;

- To run financial planning ideas past an expert from time to time; and

- To help decide what to do with your investments.

This can be an area of differentiation if the planner has a specific expertise in dealing with a certain type of offering or service as seen through the eyes of the client. Clearly the more specific a planner can describe the job they do from the client’s perspective or the outcome the prospective client will receive, the better.

Value Created

Understanding the broad nature of value is not easy. It can be difficult to drill into the minds of prospective clients to tease out what they value while making sure that it is unique and something that the planner can deliver. By and large, planners tend to think about value as being low cost, delivering exceptional service, or bringing high-quality services to the table. Unfortunately, this kind of thinking merely scratches the surface as to what value encompasses in the mind of the consumer.

To look at value, one needs to break value into its most basic elements. In a Harvard Business Review article titled “The Elements of Value” (hbr.org/2016/09/the-elements-of-value), the authors propose 30 elements of value broken into four categories (see the table on page 24). This can serve as the starting point for any analysis of the value that planners provide to their clients. Creating uniqueness is the result of the specific combination of elements pursued and the extent at which they are pursued. A planner could strategically select four to eight elements that can create a unique experience for the prospective client.

The elements of quality; makes money; heirloom; variety; provides access; and reduces anxiety are likely the most valued elements in financial services. These are elements that the consumer expects in dealing with any financial firm. These are not elements that a planner should focus on to differentiate their services. In creating a successful value proposition, the planner must look past these basic elements to find additional elements, or pursue it to an extent unmatched by the competition.

Here’s an example: robo-advisers have found success by focusing on the elements of “design/aesthetics” and “simplifies” to differentiate themselves. Some fund companies have found success by cornering the low-cost market to an extreme. Mint.com has focused on the “organizes” and “integrates” elements to make itself unique. With each of these examples, one can list several aspects of the business that deliver upon the value of that organization.

After identifying the elements that the planner will focus upon, the next step is to answer the question: I bring this element of value to my clients by__________.

The answer to that question is then used to complete the framework. A planner who focuses on behavioral finance may be able to own the “reduces anxiety” and “motivation” elements in the minds of the prospect due to his or her financial coaching skills. That planner may answer the question with “acting as a partner and coach.” In other cases, planners may discover that by limiting the number of clients to 100 families, they tap into the “affiliation/belonging” element of value.

Next Steps

This is an iterative process that will come together like a puzzle. And even after the exercise has been completed, the planner may feel that the value proposition has become stale. That is to be expected and will require the planner to reevaluate the framework to find what parts are not accurately describing his or her value.

During this process, it is possible that the planner discovers that there are multiple client segments, each with its unique jobs to be done or value created components. It may require the planner to manage multiple value propositions. In that case, it will be important to ensure some elements of consistency between the value propositions—or at least strive to add consistency in the future.

Finally, completing this framework does not mean the process is over. It is a fluid and ongoing process. It should be expected that the planner evolves the value proposition just as the practice evolves or as the client base evolves. Although a planner may initially decide that only one of the three components of the framework is unique to their practice, he or she may determine during subsequent iterations that more complete and detailed answers can be found.

The planner is on a path, continually striving to better articulate the value that he or she brings to a client and creating a business that brings more value to the client.

Mike Lecours, CFP®, is a financial adviser and marketing manager at Ohanesian/Lecours Investment and Advisory Services in West Hartford, Connecticut.