Journal of Financial Planning: March 2018

Stephen C. Brody, CFP®, ChFC®, RLP®, EdD, has been a practicing financial life planner for 30 years. He serves as an affiliate faculty member at Creighton University, a lead financial educator in many large corporations, a mentor to rising financial life planners, and is the author of What Your Happiest Friends Already Know: The Ultimate Guide to Connecting Your Money and Values with Your Life.

Two giants of our profession, George Kinder and Dick Wagner, have long professed the tremendous role and opportunity we, as financial planners, have to impact the lives of our clients, their families, communities, and the greater good. This happens within a financial life planning (FLP) engagement with the emergence and evolution of the client from who they are, to who they hope to be.

In pursuit of learning more about how to intentionally bring about such a transformational experience, I interviewed 25 leading financial life planning experts and trainers about their experiences and perceptions of the role spirituality plays in the practice and profession of FLP. Those interviewed as part of my doctoral research represented the four main FLP training platforms: the Kinder Institute, Money Quotient, the Sudden Money Institute, and Values-Based Financial Planning.

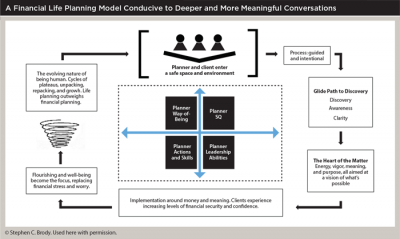

My intention during the interviews was to explore the effect of spirituality on the clients, planners, process, and outcome of an FLP engagement. The results revealed a set of attributes that enable a financial planner to intentionally create an environment and engagement conducive to deeper and more meaningful conversations, and hence a more effective FLP engagement for all involved. The attributes necessary included: (1) a heightened level of leadership and facilitation brought forth by a planner; (2) the planner doing their own work around money; (3) a developed way-of-being; (4) competency with the skills of spiritual intelligence (SQ); and (5) using a set of actions and skills to navigate a defined process and a glide path to discovery.1

A Word about “Spirituality”

Given how polarizing and problematic the term “spirituality” is for many, a brief word about the term: the word can be viewed as faith-based or faith-neutral, it has a limitless number of definitions, and it is different than religion. Within my interviews and the subsequent study of the responses, spirituality was defined as “a client’s personal search for meaning and connectedness in life events.”

Additionally, spirituality is an interdisciplinary concept existing within many fields, viewed as a universal and fundamental aspect of being human, and is an integrating factor that develops and evolves across the span of life in the form of an ongoing quest for meaning, purpose, and direction.2

Spirituality and Well-Being

To ground the results of my study, it should be understood that spirituality has a reliable relation to well-being, which is when individuals flourish in life by experiencing positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishments—what author Martin Seligman refers to as PERMA in his book, Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. The area of meaning, according to Seligman, refers to us being our best as individuals when we are focusing on something greater then ourselves, and experience feelings of purpose in life, and contributing or belonging to something greater than oneself.3 Foundationally, spirituality leads to meaning and connectedness in life events for our clients, which serves as a prerequisite to them flourishing, and ultimately to well-being.

That foundational premise was supported in the research, and affirmed the presence and role of spirituality in the FLP process as a key component to the success of a FLP engagement.

However, a large percentage of planners have no training or professional development working with clients on non-financial issues.4 To overcome the lack of training in the art and science of enhanced discovery, planners need to go farther personally to better lead and facilitate professionally. To do so, consideration should be given to the key factors linked to creating a spiritually infused environment that encourages deeper and more meaningful conversations, and planner attributes that result in more effectively facilitating a client’s personal search for meaning and connectedness in life events.

Six Key Planner Attributes

Six areas controlled by the planner are necessary to create a spiritually open environment and engagement. The factors relate to the planner, the planning process, and the meeting space. It is worth noting that although the planner can control the factors to create an environment conducive to deeper and more meaningful conversations, it is ultimately the client who determines whether the engagement focuses on money, meaning, or both.

Four of the factors identified in my study relate to planners themselves. Overwhelmingly, the way-of-being of the planner was the dominant factor and tool impacting the level of spiritual engagement. Way-of-being is composed of presence, openness, encouraging wonder, being non-judgmental, and personal planner preparation.

According to the interview participants, for the planner to be effective, he or she needed to “show up ready to be nowhere else,” “open to connecting,” and “see the client free of any judgment or bias,” while simultaneously “seeing that person as their highest possible self.” Planner self-preparation embraces that “we can only take others as far as we’ve taken ourselves,” and “the best way to create the environment is for the environment to reside within.”

The second planner-related factor was spiritual intelligence, or SQ. SQ is a set of 21 skills that can be learned so as to behave with wisdom and compassion, while maintaining inner and outer peace, regardless of the situation. SQ begins where emotional intelligence (EQ) ends, and is the best of the head and heart coming together. It is viewed as our basic need for experiencing deep meaning, essential purpose, our most significant values, and to living a deeper, wiser, more questioning life.5

The third tier of factors also relate to the actions of the planner. Three general categories of actions emerged: listening, asking questions, and miscellaneous skills. Listening needed to be active, deep, quiet, selfless, open, and non-judgmental. Asking questions was another often-mentioned skill by the interviewees. Beyond using open-ended questions free of judgement, participants talked about the questioning process needing to provide a “glide path to discovery.” Aiding the process, according to those interviewed, were skills such as appreciative inquiry, motivational interviewing, rounding, and reframing.

The fourth factor was the planner’s ability to function as a leader. Utilizing a unique set of attributes linked to current leadership theories, the planner can exponentially impact and heighten his or her effectiveness as a change agent for the client. The applicable leadership theories, when combined, contribute to a model depicting the essential leadership traits of a financial life planner.

The process utilized in the FLP engagement was the fifth factor to have a bearing on the presence of creating a spiritually infused experience open to deeper and more meaningful conversations. Participant responses from the study referred to the need for the process to be purposeful, intentional, and “done in such a way the client is confident the planner knows the route for the journey ahead.” Results revealed that the process needs to be a well-structured co-creative one that helps the client to reflect and get in touch with what’s important to them.

The sixth and final factor concerns the location or space of the actual engagement. This refers to both the physical space as well as the atmosphere of the space. Responses about the physical space showed the need for it to be free of rigidity, quiet, calming, and peaceful. And the atmosphere of the space should be “a safe container,” with safety based on the planner’s way-of-being, openness, and having a non-biased and loving posture. Many interviewees described the space as “sacred.”

The Evolving Nature of Planning

In my 2008 book, What Your Happiest Friends Already Know: The Ultimate Guide to Connecting Your Money and Values with Your Life, I wrote that FLP is “an approach to planning that places the interior history, transitions, goals, and principles of the client at the center of the planning process. It is literally a matter of connecting your money and your values with your life. For the adviser, the life of the client becomes the axis around which the financial plan develops and evolves. In FLP, the client is at the center of the plan, and the money is simply the details to support a life well lived.”

While that still has its place, my 2016 doctoral research study assessing the role of spirituality in FLP has evolved into a new definition. I propose that spiritually sensitive, or said less problematically for many, inspired financial life planning (IFLP) is a process that seeks the development of the whole person. It is grounded in discovery and awareness that leads to the understanding of one’s meaning, purpose, and moral framework for relating with self and others. Based on that understanding, a utilization of resources plan is co-created to include money and human capital, which is aligned with the client’s vision of their ideal self and life. Lastly, it provides a framework to support the ebbs and flows of life, changes in resources, and the evolving nature of being human.

When considering the definition of IFLP, and combining it with the data revealed in the research, a model of FLP conducive to deeper and more meaningful conversations emerges.

Practically Speaking

Financial life planners today need technical competence; however, to be a client-centered planner who maximizes and engages the client’s potential, training in the areas of coaching, guiding, and leading are also necessary. In addition, the ability to be present, empathetic, and emotionally and spiritually intelligent are a prerequisite to deeper and more meaningful conversations. The professional development of planners falls on the planner and the profession. Planners must be willing to do their own work that is grounded in an understanding of meaning and purpose, utilizes a process of reflection and discernment, emphasizes spirituality-based self-care, and includes discovery and awareness of one’s own relationship with money.6

Our profession must also elevate the current core pedagogy beyond the technical to include the skills relating to counseling, education, coaching, and leadership. As Dick Wagner wrote in his 2016 book, Financial Planning 3.0: Evolving our Relationships with Money, planners don’t need to be the ultimate authority on everything, but “being a part of a profession means every member must master its basic craft.”

We are then left with needing to courageously and boldly address the question: what is considered our basic craft? Do we move forward and continue to only address money, or do we strive for the loftier goal of engaging in deeper and more meaningful conversations that connect money and meaning, and ultimately affect the greater good?

Our potential is too great, our time too short, and the yearning of our clients is too deep to not push beyond our self-imposed boundaries and limitations to fulfill the promise of our profession. With that, imagine it’s five years from now, and in looking back, our profession has thrived. It’s truly amazing. We are doing the work we were put here to do, and passion, purpose, and meaningful abundance is rampant for clients and planners. In fact, the profession has become everything we could have ever hoped it would be.

The question then, and the impetus for what’s next, is: what would have to happen for you personally and within the profession to enable you to feel that way? I urge you to freely envision, unencumbered by the past or present or the minutia of our times, and then to boldly go forth to re-create your future, and the future of our profession.

Endnotes

- For more details, see the author’s 2016 doctoral dissertation, “Assessing Spirituality in Financial Life Planning” at the Creighton Digital Repository hdl.handle.net/10504/108224.

- See the following resources: the 2013 Philip Sheldrake book, Spirituality: A Brief History; the 2009 Edward Canda and Leola Furman book, Spiritual Diversity in Social Work Practice: The Heart of Helping; the 2005 David Derezotes book, Spiritually Oriented Social Work Practice; and the research paper, “An Inclusive Definition of Spirituality for Social Work Education and Practice” in the August 2013 Journal of Social Work Education.

- See also, “From Functioning to Flourishing: Applying Positive Psychology to Financial Planning” in the November 2015 Journal of Financial Planning.

- See “The Changing Role of the Financial Planner Part 1: From Financial Analytics to Coaching and Life Planning” in the August 2009 Journal of Financial Planning.

- See the 2012 Cindy Wigglesworth book, SQ-21: The Twenty-One Skills of Spiritual Intelligence and the 2001 Danah Zohar and Ian Marshall book, SQ: Connecting With our Spiritual Intelligence.

- See the author’s dissertation, “Assessing Spirituality in Financial Life Planning,” as well as “Financial Integration: Connecting the Client’s Past, Present, and Future” in the May 2005 Journal of Financial Planning; “Psychology and Life Planning” in the March 2007 Journal of Financial Planning; and “Spiritually Sensitive Professional Development of Self: A Curricular Module for Field Education” in the April 2010 Social Work and Christianity.

Learn More:

Join Stephen Brody at FPA Retreat, April 23-26, where he will discuss his research-based model for creating financial planning engagements steeped in deeper and more meaningful conversations.

Learn more at FPARetreat.org.