Journal of Financial Planning: March 2021

Executive Summary:

- This article examines several decumulation strategies for a client approaching retirement with a mix of tax-favored retirement accounts and taxable accounts, each holding appreciated stocks and taxable bonds.

- The analysis applies these strategies to three “nest egg” scenarios to determine their resulting portfolio lives, while examining tax consequences throughout those lives.

- In these scenarios, the more tax-efficient decumulation strategies last from 1 to over 11 percent longer than both the Conventional Wisdom and Schwab’s recently marketed decumulation strategies.

- The results provide insights that financial planning professionals can use to tailor tax-efficient decumulation recommendations that better fit a client’s particular situation, increasing how long their wealth lasts during retirement.

Greg Geisler, Ph.D., is a clinical professor of accounting at the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University (Bloomington). His work has been published in many journals, including six other articles in the Journal of Financial Planning. He is the 2017 recipient of the Journal’s Montgomery-Warschauer award. He can be reached HERE.

Bill Harden, CPA, ChFC®, Ph.D., is an associate professor of accounting in the Bryan School of Business and Economics at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro. He researches and consults in the areas of taxation and financial planning for small businesses and individuals. He can be reached HERE.

David S. Hulse, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the Von Allmen School of Accountancy and the Martin School of Public Policy at the University of Kentucky. He has published tax-related articles in many journals and is a contributing author and co-editor for a federal taxation textbook. Email him HERE.

NOTE: Click on Tables and Figures below for PDF versions of the images. Click here to view this article in the digital edition.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

An important part of the financial plan is determining the sequence of withdrawals (i.e., decumulation). Because of differing tax treatment for various types of accounts in which a client might save for retirement, different decumulation strategies result in different portfolio lives.1

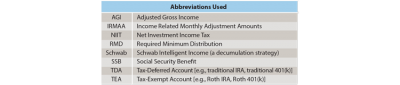

This article’s analysis considers important tax consequences, such as tax rates that apply to income from tax-deferred accounts (hereafter, TDAs; see “Abbreviations Used” box for a list of abbreviations used in this article). It also considers tax rates on appreciated stocks sold from taxable accounts, the tax torpedo [i.e., additional income causing additional Social Security benefits (SSBs) to be taxable],2 required minimum distributions (RMDs), Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amounts (IRMAA) for higher-income clients participating in Medicare (i.e., increase in Medicare premiums, which is effectively additional tax), and the 3.8 percent net investment income tax (NIIT).

This analysis focuses on a client retiring at age 65 but not starting SSBs until age 70, creating a five-year window in which income can be recognized without incurring the tax torpedo. This analysis also examines tax consequences throughout the portfolio’s life, which is important because a tax-efficient strategy in the shorter run may not be so in the longer run. The longer-run examination here accounts for the scheduled expiration at the end of 2025 of the tax cuts enacted in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.3

There is no single best approach for all clients. This analysis shows that the optimal decumulation strategy varies among clients, depending on their specific circumstances, which includes the cash flow needed in retirement and the fraction of savings held in various types of investment accounts. The analysis examines three “nest egg” scenarios and finds that a specific client-focused strategy performs better than generic rules of thumb that are not client-focused. The client’s ability to defer the start of SSBs also provides more flexibility in managing the tax impacts of the decumulation.

Background on Decumulation Strategies

Most studies on this topic [Reichenstein (2006) and Horan (2006a, 2006b), Jennings et al. (2011), and Coopersmith and Sumutka (2011)] note a commonly employed decumulation strategy referred to as the Conventional Wisdom, which decumulates taxable accounts first, TDAs second, and tax-exempt accounts (TEAs) last. The idea behind this strategy is to first liquidate the taxable accounts, which are often seen as tax-disadvantaged. An advantage of taxable accounts, however, is the reduced tax rates for long-term capital gains, which can be as low as zero percent. Long-term capital gains arising in TDAs are taxed as ordinary income when distributed. In addition, after an individual attains age 72, RMDs apply to TDAs but not for taxable accounts and TEAs.4

Charles Schwab has recently marketed another decumulation strategy, which it calls “Schwab Intelligent Income” (hereafter, Schwab). It is advertised as generating “tax-smart withdrawals,” combining annual distributions from both TDAs and taxable accounts, so both are exhausted in the same year.5 This strategy has some intuitive appeal. Under the Conventional Wisdom, an individual might waste low tax brackets in the early years of retirement when taxable investments being sold to meet spending needs include tax-free returns of basis. Conventional Wisdom can result in a higher tax bracket in the middle years of retirement when TDAs are the only source of funds. Under the Schwab strategy, combining sales of taxable investments and TDA withdrawals every year takes advantage of lower tax brackets in early years and avoids higher tax brackets later. It is unclear, however, whether Schwab is more tax-efficient than the Conventional Wisdom when considering tax law features like the SSB tax torpedo, IRMAA, and the NIIT. This research provides evidence on that question for three client scenarios.

An additional complication often not factored into decumulation strategies is the SSB tax torpedo, which can cause the effective marginal tax rate to be 150 or 185 percent of the statutory tax rate because additional non-SSB income can cause more SSBs to be taxed. The worst part of the tax torpedo is 185 percent of the (post-2025) 25 percent statutory tax rate, resulting in an effective marginal tax rate of 46.25 percent.6 Clients who delay taking SSBs obtain increased SSBs of eight percent per year after passing their full retirement age, until reaching age 70. This delay also creates a window of time where the tax torpedo does not occur. A client can take advantage of this window by recognizing income that is taxed at the statutory tax bracket rather than 150 or 185 percent of it. Thus, a retiring client can benefit from engaging in strategies such as harvesting long-term capital gains and making partial Roth conversions in the years before SSBs start. For higher-income individuals with larger nest eggs, “IRMAA bumps” and the NIIT are additional issues a financial planner needs to consider.

Literature Review

There is extensive literature on non-tax aspects of decumulating retirement savings, much of which focuses on investment choices and sustainable withdrawal rates [Bengan (1994), Guyton (2004), Fullmer (2007), Pfau (2011)]. This study’s focus, however, is on the tax considerations for decumulation strategies, so this literature review focuses on studies for which such tax aspects are a primary focus.

Reichenstein (2006) and Horan (2006a, 2006b) examined tax-efficiency to increase the life of a portfolio that includes taxable accounts, TDAs, and TEAs. In their discussion of tax-efficient retirement withdrawal strategies, Jennings et al. (2011) pointed out that those earlier studies showed it is tax-efficient to sell taxable accounts before taking TDA distributions (except when taking RMDs), and it is best to take TDA distributions until taxable income reaches the top of a tax bracket and then take TEA distributions to generate cash flow while avoiding the next higher tax bracket. Geisler and Hulse (2018) noted that effective tax brackets are more complicated than statutory tax brackets due to the SSB tax torpedo. They also noted that effective tax brackets can decrease as income increases because the tax torpedo is limited to when taxable SSBs are less than 85 percent of SSBs. The findings of these studies are incorporated into the more tax-efficient strategies in this research.

Coopersmith and Sumutka (2011) examined a “common rule” of using taxable savings before TDAs and compared it to a tax-efficient linear programming model designed to optimally balance taxable account and TDA withdrawals. Their study shows the importance of incorporating specific tax factors into the decumulation decision.

Sumutka et al. (2012) examined 15 strategies (three naïve and 12 informed strategies for various aspects of the tax system) and found that TDA withdrawals in earlier years to use low tax brackets in those years have a beneficial effect. They also found that maintaining a smooth level of income to avoid bumps in Medicare premiums and the NIIT—and maintaining the lower long-term capital gains rate—improves tax efficiency. Their study reinforces the idea that minimizing taxes in the earlier years of retirement might not improve overall wealth because of the increase in taxes later. Their study and Coopersmith and Sumutka (2011) did not consider the situation where the start of SSBs is delayed until age 70. This delay creates a window of opportunity to take advantage of low statutory tax rate brackets before the higher effective tax brackets due to the beginning of the tax torpedo, an important aspect of this research.

Welch (2015) also compared “common practice” with a linear programming approach. This work expands on Coopersmith and Sumutka (2011) by including the ability to make Roth conversions and uses a single rate of return on all accounts to focus on the tax effects. He found significant improvements over the common practice.

Cook, Meyer, and Reichenstein (2015) suggested a tax-efficient decumulation strategy in which taxable (i.e., partial Roth) conversions are used to move amounts from TDAs to TEAs to take advantage of the two lowest ordinary tax rate brackets during earlier years in which taxable investments are the primary source of spendable funds.7 They find this to be more tax-efficient than the Conventional Wisdom as it lowers the average tax rates across the years involved. Geisler and Hulse (2018) expanded this work by showing that financial planners should also consider the SSB tax torpedo. Neither work considers appreciated stocks owned in taxable accounts, which this research considers.

Kitces (2019a) noted that clients should also be aware that increased ordinary income can increase the long-term capital gains tax rate, which can be zero, 15, or 20 percent, depending on taxable income. He recommends recognizing ordinary income through partial Roth conversions or other means only to the extent of deductions, so it is effectively taxed at zero percent, as well as harvesting long-term capital gains to the top of the zero percent bracket for this type of income (taxable income of $40,400 if single and $80,800 if married filing jointly, for 2021).

Kitces (2019b) recommended finding an equilibrium tax rate throughout retirement years. A challenging practical aspect of this goal is the different effective marginal tax rates a retiree can face before versus after SSBs begin. Further, even with a consistent taxable income in real dollars every year, it may not be possible to maintain an equilibrium tax rate because the tax torpedo shifts over time due to its dollar thresholds not being indexed for inflation, a phenomenon discussed in more detail later. Nonetheless, Kitces’ main point that one should not defer too much income in the early years of retirement is good advice; it is beneficial to defer enough income to avoid high marginal tax rates in the early years but not so much that it causes high marginal tax rates in the future.

Reichenstein (2019) pointed out the value of partial Roth conversions during the client’s 60s, especially before SSBs begin, and using Roth accounts as a source of tax-free cash later to avoid higher Medicare premiums. Kitces (2020) noted that many strategies tend to lower current tax rates but also lead to higher future tax rates, which can be tax inefficient.

The literature shows that one-size-fits-all decumulation strategies, like the common practice and Conventional Wisdom, can be improved upon by focusing on a given client’s specific tax situation. It also shows the tax benefits of focusing on the entire life of a retirement portfolio to avoid “bumps” in marginal tax rates. While sophisticated mathematical techniques can result in even better outcomes, adapting the intuition for these outcomes to a client’s specific tax situation can be difficult if one is not well-versed in such techniques.

Description of Analysis

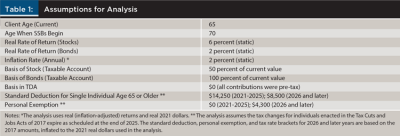

Assumptions for this research are summarized in Table 1. Two of them are that the client is retiring at age 65 but will not begin taking SSBs until age 70. For many clients, a primary goal is maximizing the length of time their retirement portfolio will last given a certain spending need. Delaying SSBs is actuarially advantageous if the client has an above-average life expectancy and is also a risk aversion strategy, so the analysis here focuses on the life of the client’s retirement portfolio rather than the probabilities of it surviving to various ages. A third assumption is that returns are static, so tax effects of the different strategies can be examined without confounding effects from other factors. This assumption is consistent with prior tax literature in this area.

The analysis assumes the client has accumulated savings in TDAs, TEAs, and taxable accounts. The fraction of total savings in each of these accounts varies among the three nest egg scenarios. The analysis also assumes the client wants to withdraw funds from these accounts to have, with any SSBs, a consistent level of annual after-tax cash to spend.

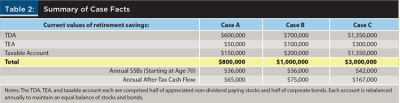

Three nest egg scenarios are analyzed. In Case A, the client has accumulated $800,000, will receive annual SSBs of $36,000 starting at age 70, and needs an annual after-tax cash flow of $65,000. Based on the authors’ experience, this type of client typically has most of their retirement savings in TDAs, with smaller balances in TEAs and taxable accounts. Accordingly, the TDA is worth $600,000, the TEA $50,000, and the taxable account $150,000. Table 2 summarizes the three cases’ facts.

Four tax-aware decumulation strategies are applied to Case A. Two are the Conventional Wisdom and Schwab strategies discussed earlier. The third strategy (Harvest) applies the Kitces (2019a) methodology of both harvesting long-term capital gains at the zero percent tax rate and doing partial Roth conversions that are offset by deductions, so they are effectively taxed at a zero percent rate in the early years of retirement, before SSBs begin. After SSBs begin, such income recognition is managed to avoid for as long as possible the worst part of the SSB tax torpedo, where there is a 46.25 percent effective tax rate. These adaptations are discussed further with the results for Case A.

The fourth strategy is client-focused in that this particular client can avoid the worst part of the SSB tax torpedo by accelerating income, so that this avoidance occurs for the life of the portfolio. Specifically, during early retirement years before SSBs begin, taxable accounts are gradually liquidated, and partial Roth conversions and sizeable TDA withdrawals also occur to the extent they fully use the lowest two tax rate brackets. After SSBs start, TDA withdrawals are taken up to (but not into) the worst part of the tax torpedo, with TEA withdrawals supplying any additional funds needed.

In Case B, the client has a larger nest egg of $1,000,000, with a TDA worth $700,000, a TEA worth $100,000, and a taxable account worth $200,000. The client again receives annual SSBs of $36,000, but the desired annual after-tax cash flow is now $75,000. The Conventional Wisdom, Schwab, and Harvest strategies are again examined, but the client-focused strategy is modified. Specifically, during early retirement years before SSBs begin, larger partial Roth conversions and TDA withdrawals occur than in Case A. While this results in some of them being taxed at the third (22 percent, for 2021-2025) tax rate bracket in these early years, it also ensures that the subsequent effective marginal tax rate never reaches 46.25 percent in any year.

In Case C, the client has accumulated $3,000,000, will receive annual SSBs of $42,000, and needs annual after-tax cash flow of $167,000.8 The authors’ experience with clients in this situation is that they typically accumulate a larger portion of their savings in taxable accounts. The client is assumed to have a TDA worth $1,350,000, a TEA worth $300,000, and a taxable account worth $1,350,000. Given these parameters, the client’s income will be high enough to trigger IRMAA and NIIT in some years, depending on the decumulation strategy.9 IRMAA generally is based on adjusted gross income (AGI), while the NIIT applies only to taxable investment income (but not TDA withdrawals) when AGI exceeds the $200,000 statutory threshold for a single individual. Also, this $200,000 threshold effectively decreases each year because it is not adjusted for inflation, but the IRMAA thresholds are inflation-adjusted.

The Conventional Wisdom and Schwab strategies are similarly applied to Case C. The Harvest strategy is not examined for Case C because it is difficult to meet the client’s $167,000 annual cash needs while limiting taxable income to the $40,400 amount to which the zero percent long-term capital gains tax rate applies. Thus, the third strategy is client-focused and avoids the 32 percent income tax bracket the first five years, and it avoids the (post-2025) 28 percent bracket every year after that (except when RMDs compel larger TDA withdrawals). The fourth strategy, which is also client-focused, avoids an additional IRMAA bump (i.e., the increased Medicare premiums if AGI exceeds a threshold by $1). The SSB tax torpedo is of lesser importance in Case C because it is incurred in full in many years due to the client’s income level, regardless of the strategy employed.

When analyzing the strategies for the three cases, the following additional assumptions are made and are noted in Tables 1 and 2. Half of each account consists of appreciated non-dividend paying stocks,10 and the other half is corporate bonds. The stocks and bonds have 6 and 2 percent annual static real returns, respectively,11 and inflation is a static two percent annually.12 Each account is rebalanced annually to maintain equal amounts of stocks and bonds, thus, avoiding a portfolio that becomes stock heavy as the client ages.13 The analysis assumes that the individual income tax rates in the law since 2018—which are scheduled to sunset at the end of 2025—will indeed sunset. Similarly, the analysis assumes that this sunsetting reverts the standard deduction to its previously lower inflation-adjusted base amount and reinstates the personal exemption deduction. The client takes the standard deduction.

Results of Decumulation Strategies

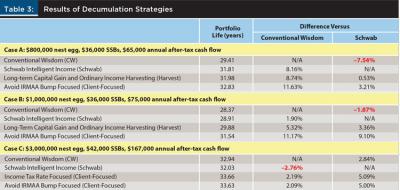

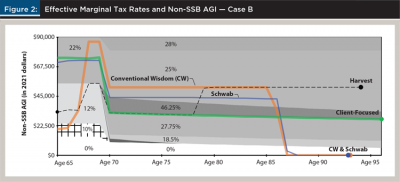

This section describes the results of applying four decumulation strategies to the three cases. Table 3 summarizes the results, and Figures 1, 2, and 3 depict their comparative tax rates.

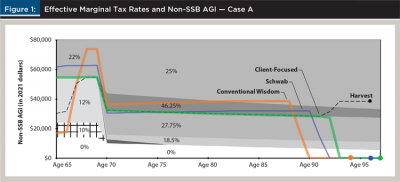

Case A: $800,000 Nest Egg, $36,000 SSBs

Figure 1’s shaded areas depict the effective marginal tax rates on the client’s non-SSB ordinary income across the retirement years. The four lines represent the non-SSB income resulting from the four decumulation strategies. To focus on the tax rates, ignore for now the lines for the four strategies. As previously noted, the tax torpedo refers to an additional dollar of non-SSB AGI causing additional SSBs to be taxable, making the effective marginal tax rate 185 percent of the statutory tax rate.14 Figure 1 depicts this overlap of statutory tax brackets with the phase-in of SSBs’ taxability. The first five years show only statutory tax rates because there are no SSBs to trigger the tax torpedo (SSBs do not begin until age 70 for this client). In later years, the tax torpedo can cause portions of non-SSB income to be taxed at 18.5, 27.75, and 46.25 percent, corresponding to 185 percent of the (post-2025) 10, 15, and 25 percent statutory tax brackets. However, after the maximum 85 percent of SSBs is taxable, the client again faces only the statutory tax rates (i.e., 25 percent). The 18.5, 27.75, and 46.25 tax rates slope downward over time in Figure 1 because the thresholds for phasing in SSBs’ taxability (e.g., $25,000 and $34,000 for a single individual) are not adjusted for inflation, so they gradually decrease in real dollars.

Figure 1 makes clearer the opportunity to realize income that is taxable at lower rates during the years after retirement begins and before SSBs begin. Proper planning to effectively use this opportunity can noticeably improve portfolio lives. During these years when there are not yet any SSBs, other income can be higher to support the annual cash needed, without incurring significantly higher tax rates.

The four lines depict non-SSB AGI across years for the four decumulation strategies. Such income includes TDA withdrawals, partial Roth conversions, long-term capital gains, and taxable interest. For example, the Conventional Wisdom decumulates taxable accounts first, TDAs second, and TEAs last. The orange line in Figure 1 shows a low amount of non-SSB AGI for a few years (because much of the proceeds from selling investments in taxable accounts is a tax-free return of basis). For several years after that, the client is relying on taxable TDA withdrawals (less so after SSBs start at age 70). At age 89, the TDA is exhausted, and the client has zero non-SSB AGI because income is comprised solely of TEA withdrawals and SSBs (a small fraction of the SSBs is taxable but is fully offset by deductions). The portfolio’s life is 29.41 years (see Table 3); the large dots near the right edge of Figure 1 indicate the last full year of the portfolio’s life, but not any fractional year beyond that.15

The fact that the TDA runs out well before the TEA indicates a tax inefficiency of the Conventional Wisdom strategy because there is zero tax those last few years. Tax inefficiencies like this are inherent in several strategies that focus on short-term impacts as opposed to the entire life of the portfolio. A zero tax in later years may seem advantageous, but tax efficiency could be improved because there is no utilization of lower tax rates in those years.

Recall that the Schwab strategy uses taxable account and TDA withdrawals (but not TEA withdrawals) from the first year of retirement to meet cash flow needs. This results in those two accounts lasting until age 91. TEA withdrawals occur for six years after that, resulting in a total portfolio life of 31.81 years (see Table 3). As can be seen by comparing the blue and orange lines in Figure 1, the portfolio lasts longer with the Schwab strategy than the Conventional Wisdom, and this is primarily due to avoiding most of the tax torpedo’s worst part from ages 70 through 91. In this case, the Schwab strategy improves portfolio life by 8.16 percent compared to Conventional Wisdom.

Turning to the two more tax-efficient strategies, Harvest recognizes long-term capital gains to take advantage of the zero percent rate applicable for them and partial Roth conversions to be offset by deductions. As with Conventional Wisdom, the taxable accounts are exhausted at age 67. After that, the client takes TDA withdrawals to fully use the 12 percent tax bracket as well as TEA withdrawals to supply the rest of the cash flow needed. This continues after SSBs begin, although it takes fewer TDA and TEA withdrawals to meet those objectives due to the SSBs’ presence. Because the start of SSBs at age 70 coincides here with the reinstatement of pre-2018 tax rates, the client takes TDA withdrawals to fully use the 15 percent statutory tax rate bracket (27.75 percent effective rate). The portfolio lasts 31.98 years, which is 8.74 and 0.53 percent longer than the Conventional Wisdom and Schwab strategies, respectively. As shown by the dashed line in Figure 1, an important reason for this result is the avoidance of the worst part of the tax torpedo (i.e., 46.25 percent effective rate) in most years.

The final strategy is client-focused. It is similar to the previous strategy, except it also uses larger TDA withdrawals and partial Roth conversions the first five years (from beginning of age 65 through end of age 69) to take full advantage of the zero percent tax rate for long-term capital gains and 12 percent tax bracket for ordinary income.16 After SSBs begin, TDA withdrawals are made so non-SSB income reaches, but does not enter, the worst part of the tax torpedo. The portfolio lasts 32.83 years (until age 97), which is 11.63 and 3.21 percent longer than for the Conventional Wisdom and Schwab strategies, respectively. A comparison of the green and black dashed lines in Figure 1 shows that the reason this final strategy lasts longer is because it fully utilizes the 12 percent tax rate bracket the first few years of retirement, thus avoiding more income taxed at an effective rate of 46.25 percent after turning age 93. That is, it trades off more income taxed sooner at a low rate against a higher effective tax rate decades later.

Case B: $1 Million Nest Egg, $36,000 SSBs

Recall that Case B is the same as Case A, except the client’s nest egg and annual cash flow needs are moderately larger. Figure 2 depicts the effective tax rates on non-SSB income that would result each year from applying the four decumulation strategies. As shown in the orange line, the Conventional Wisdom strategy again quickly exhausts the taxable accounts (by age 67). The client follows this with 19 years of TDA withdrawals (to age 86) and finishes with about seven years of TEA withdrawals (to age 93). The total life of the portfolio is 28.37 years (see Table 3). This strategy suffers from not using lower tax brackets to their fullest extent possible before SSBs begin and incurring the worst part of the tax torpedo after they begin.

Using the Schwab strategy, the client withdraws funds first from both taxable accounts and TDAs, proportionately, and TEAs last. The portfolio’s life is 28.91 years, which is slightly longer than that for the Conventional Wisdom strategy. As can be seen in the blue line in Figure 2, the Schwab strategy results in more non-SSB AGI being taxed at 22 percent during the first few retirement years than with the Conventional Wisdom strategy, but the pattern of non-SSB AGIs are somewhat similar starting at age 70, including the reliance on only SSBs and TEA withdrawals the last several years. Thus, as with the Conventional Wisdom strategy, a tax inefficiency of the Schwab strategy is its lack of utilization of lower tax rates in later years. The Schwab strategy slightly outperforms Conventional Wisdom, by 1.90 percent.

The Harvest strategy uses partial Roth conversions and sales of assets in taxable accounts to end up with $0 tax the first few years, thus, taking advantage of the lower brackets and resulting in a portfolio life of 29.88 years, which is 5.32 percent longer than Conventional Wisdom and 3.36 percent longer than the Schwab strategy. The dashed line in Figure 2 provides insights into this outcome. During most of the client’s 70s, taking TDA withdrawals to the top of the 27.75 percent effective tax rate bracket avoids the 46.25 percent effective marginal tax rate until the TEA is exhausted at age 79, but it also requires some TEA withdrawals to meet the rest of the after-tax cash needed. After that, the client must make larger TDA withdrawals to obtain the after-tax cash needed, which pushes them above the effective 46.25 percent tax rate (i.e., fully through the tax torpedo) and into the statutory 25 percent tax rate every year.

The fourth decumulation strategy is client-focused in that it tailors the previous strategy to the Case B client’s unique situation. Recall that the Harvest strategy avoids the 46.25 percent effective tax rate for several years but is forced above that from age 79 to the portfolio’s demise in the client’s mid-90s. The fourth strategy looks ahead by structuring taxable asset sales, partial Roth conversions, and TDA withdrawals in the first five years (i.e., triggering a lot more income than Harvest—well into the 22 percent tax bracket) so that in the remaining years when SSBs are received, TDA withdrawals push taxable income to the top of the 27.75 percent effective tax rate (which is the same as the top of the post-2025 15 percent statutory tax bracket). Thus, the TDA and TEA are both exhausted in the portfolio’s final year, and the client avoids the 46.25 percent effective tax rate (i.e., worst part of the tax torpedo) in all years. Another advantage of this tailored strategy of accelerating income before SSBs begin is that the lower tax brackets are effectively wider before SSBs begin at age 70 because there is no tax torpedo.

The green line in Figure 2 depicts the outcome of this strategy, which increases the portfolio’s life to 31.54 years (5.56 percent longer than for the Harvest strategy). Interestingly, the client pays more annual tax in the first five years than in later years, but the acceleration of income in the first five years that leads to that higher annual tax is what allows later TDA withdrawals to avoid the 46.25 percent effective tax rate in all subsequent years. This fourth strategy leads to the portfolio lasting longer than the other strategies, as was true in Case A. This strategy is consistent with the point of Kitces (2019b) that a best practice is finding an equilibrium marginal tax rate. In this case, this rate is 22 percent while the tax rate cuts under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 are in effect and an effective marginal tax rate of 27.75 percent after they sunset (and SSBs begin) at the start of 2026.

Case C: $3 Million Nest Egg, $42,000 SSB

This case involves a higher-income client, with a $3 million nest egg, $42,000 of SSBs (close to the maximum), and $167,000 of annual after-tax cash flow needed. The high level of income necessary to generate this cash requires consideration of IRMAA and the NIIT. The taxation of SSBs is of less concern in this case because the income required to generate $167,000 of after-tax cash means that the maximum 85 percent of SSBs will be taxable for most, or all, of the years in the portfolio’s life, depending on the decumulation strategy.

Let’s now consider the four decumulation strategies. RMDs starting at age 72 are a more important consideration for this case than in the previous cases. The larger fraction of the nest egg held in taxable accounts in Case C allows the client to rely less on TDA withdrawals before age 72, but the higher resulting TDA balance can force the client to deviate from a selected strategy starting at age 72 because of RMDs. The Conventional Wisdom strategy is, thus, modified so the client takes the full RMD, withdrawing the required amount of funds from the TDA, followed by the taxable accounts to attain the after-tax cash flow of $167,000 (with rebalancing, as necessary, in all the accounts to maintain equal amount of stocks and bonds in each).17

For more tax efficiency, a different focus than in Cases A and B is necessary. As noted previously, the Harvest strategy is not examined for Case C because it is difficult to meet the client’s $167,000 annual cash needs while limiting taxable income to the $40,400 amount to which the zero percent long-term capital gains tax rate applies. Two client-focused strategies are, thus, examined. One of them focuses on avoiding a significantly higher income tax rate every year, and the other one focuses on avoiding a significant IRMAA bump in Medicare premiums by keeping AGI $1 below an IRMAA threshold every year. A financial planner can carefully plan with this type of client how best to decumulate their accounts to balance the objectives of avoiding higher Medicare premiums (this fourth strategy) and avoiding higher income tax rates (the third strategy).

Turning first to the Conventional Wisdom strategy, the taxable accounts last about 13.5 years, much longer than in Case A, because a larger fraction of the nest egg is held in taxable accounts. In Figure 3, the increase in the orange line at age 78 indicates a shift to TDA withdrawals because the taxable accounts are exhausted. The orange line also increases at age 72 due to RMDs beginning. From ages 79 to 89, the client’s income is comprised solely of TDA withdrawals and SSBs, resulting in TDA withdrawals that exceed RMDs. In the last several years, the client’s income is comprised solely of TEA withdrawals and SSBs, resulting in a portfolio life of 32.94 years (age 97). In this strategy, IRMAA is incurred for ages 74 to 92,18 and the NIIT is triggered in only one year (age 78).

As with Cases A and B, exhausting the TDA before the TEA indicates tax inefficiency because the client does not take advantage of lower tax brackets during the last several years of retirement. However, unlike those cases, managing income to avoid the maximum tax torpedo in all years is not possible in Case C, so other strategies are necessary to improve the portfolio’s duration.

Following the Schwab strategy, the client withdraws funds proportionately from taxable accounts and TDAs first, and TEAs last. This results in TDA withdrawals exceeding RMDs. The taxable accounts and TDA are exhausted at age 89, as can be seen in the blue line in Figure 3. It takes seven years after that to deplete the TEA, resulting in a portfolio life of 32.03 years (2.76 percent shorter than for the Conventional Wisdom). An important reason for this shorter life is the large IRMAA bump at $138,000 of AGI. Although not shown in Figure 3 (but affecting the portfolio life shown), the $138,000 IRMAA bump occurs at $102,300 of non-SSB AGI when SSBs are being received (i.e., $138,000 minus 85 percent of $42,000 SSBs). Non-SSB AGI exceeds $102,300 for 20 such years with the Schwab strategy, and AGI exceeds $138,000 in four of the five years before SSBs begin. These 24 years begin occurring early in retirement. This excess occurs for only 17 years with the Conventional Wisdom, and these years all occur later in retirement; for the first nine years of retirement no IRMAA bump is paid. Further, the NIIT is triggered for 12 years with Schwab versus only one year for Conventional Wisdom.

A third reason portfolio life is shorter in Case C for Schwab versus Conventional Wisdom is that the average annual TDA distributions prior to age 78 are smaller for Conventional Wisdom than for Schwab. Since TDAs grow at a pre-tax rate of return, this results in almost $1,000,000 more inside the TDA at age 78 under the Conventional Wisdom than under Schwab. This more than makes up for the tax paid on the large TDA withdrawals from ages 78 to 90 under the Conventional Wisdom.

To increase tax efficiency, two client-focused strategies are examined. The first one (Income Tax Rate, shown as the dashed line in Figure 3) combines sales of assets from taxable accounts to generate cash flow and large partial Roth conversions (or RMDs, when required) to trigger income to the top of the 24 percent tax rate bracket the first five years of retirement and, for most years thereafter, slightly below the top of the post-2025 25 percent tax rate bracket until the taxable accounts are exhausted, which occurs at age 74. After that, the client makes proportionate TDA and TEA withdrawals, resulting in the TDA and TEA lasting until the end of the portfolio’s life of 33.66 years (age 98), which is 2.19 and 5.09 percent longer than for the Conventional Wisdom and Schwab strategies, respectively.

The other client-focused decumulation strategy examined (Avoid IRMAA Bump, shown as a green line in Figure 3) focuses on avoiding a further increase in Medicare premiums. The aggressive harvesting of income with the third strategy for the first several years of the portfolio’s life pushes AGI above the $165,000 IRMAA bump those years. The fourth strategy avoids the $138,000 and $165,000 IRMAA bumps every year. Specifically, by structuring TDA withdrawals after the taxable accounts are fully liquidated so the $111,000 IRMAA bump is avoided for several years, followed by TDA withdrawals so the $138,000 IRMAA bump is avoided for the remainder of the portfolio’s life, the TDA and TEA can both last until the end of such life (given Case C’s facts, it is not feasible to avoid the $111,000 IRMAA bump in all years).

Targeting the $111,000 IRMAA bump earlier than the $138,000 one reduces the present value of the latter’s larger IRMAA. However, as a comparison of the green and dashed lines in Figure 3 indicates, more income is taxed at 28 percent after age 72 with this fourth strategy than with the third strategy. Smaller partial Roth conversions are needed the first several years with this strategy than with the third strategy, so smaller amounts need to be taken from the taxable accounts to pay income taxes. Thus, the taxable accounts last longer than with the third strategy (to age 76 rather than age 74).

The net result of this fourth strategy is a portfolio life of 33.63 years, which is nearly identical to the 33.66-year life with the third strategy (age 98). This 33.63-year life is a 2.09 percent improvement over Conventional Wisdom and 5 percent over Schwab. The third strategy’s accelerated income causes a greater income tax and additional Medicare premiums the first five years of retirement than with the fourth strategy, but it is followed by significant reductions in both for the rest of the portfolio’s life. Overall for this client, this targeting of tax brackets with the third strategy fares about the same as targeting IRMAA bumps.19

Additional Analysis

Additional analysis is conducted to assess the sensitivity of the results to the main analysis’ assumptions. The first additional analysis assumes the basis of the stock in the taxable account is 10 percent of the current value, instead of 50 percent, and it also assumes that Congress does not allow sunsetting at the end of 2025 of the tax cuts that became effective in 2018 (similar to its extension about 10 years ago of the so-called Bush tax cuts). The results of this additional analysis are not presented in a table but are discussed next.

For Case A, the portfolio lives for the Schwab, Harvest, and client-focused strategies are 3.98, 7.12, and 7.78 percent longer than with the Conventional Wisdom strategy (versus 8.16, 8.74, and 11.63 percent longer in the main analysis). For Case B, Schwab lasts 0.03 percent shorter than Conventional Wisdom, while Harvest and the client-focused strategy last 5.79 and 7.56 percent longer (these three strategies’ portfolio lives are 1.90, 5.32, and 11.17 percent longer than the Conventional Wisdom in the main analysis). Overall, the two more tax-efficient strategies last between 5 and 8 percent longer than the two less tax-efficient strategies. In comparison, for the main analysis’ results reported in Table 3, the former last between 5 and 11 percent longer than the latter. For Case C, Schwab lasts 2.78 percent shorter than Conventional Wisdom, while the Income Tax Rate-focused and Avoid IRMAA Bump-focused strategies last 2.17 and 2.23 percent longer. These are only slightly different than Case C’s results for the main analysis. These results indicate that the effectiveness of the Harvest and client-focused strategies continues with the changed assumptions.

The main analysis and the first additional analysis assumed 6 and 2 percent real returns for stock and bonds, but future actual returns are uncertain. As another additional analysis, the first additional analysis is extended to consider two sets of alternative assumptions for returns. In one of them, real returns are 3 percent for stocks and 1 percent for bonds, which could be reasonable to assume if one is more pessimistic about future returns. This extended additional analysis is applied for Case B’s Conventional Wisdom and client-focused strategies, as well as Case C’s Conventional Wisdom and Income Tax Rate-focused strategies. Consistent with these lower returns, this sensitivity analysis assumes the client’s after-tax cash flow is $67,000 for Case B and $140,000 for Case C, less than the $75,000 and $167,000 for the main analysis. In the other set of alternative assumptions, real returns are 9 percent for stocks and 3 percent for bonds. In this alternative, the client’s after-tax cash flow is assumed to be $82,000 for Case B and $190,000 for Case C, higher than for the main analysis. The results of this additional analysis are not presented in a table but are discussed next.

These alternative return assumptions result in percentage increases in portfolio lives that are qualitatively similar to those in the alternative analysis. Specifically, for Case B’s $1,000,000 nest egg, the client-focused strategy lasted 6.61 percent longer than the Conventional Wisdom strategy in the low-returns scenario, and 11.73 percent longer in the high-returns scenario (compared to 7.56 percent longer with the moderate-returns in the first alternative analysis). For Case C’s $3 million nest egg, the Income Tax Rate-focused strategy lasted 1.24 percent longer than the Conventional Wisdom strategy in the low-returns scenario and 3.69 percent longer in the high-returns scenario (compared to 2.17 percent longer in the alternative analysis). The relative differences in portfolio lengths are consistent with a client-focused strategy being more important as returns increase.

Additional Items of Note

For individuals who desire to leave some assets to heirs, the situation is more complex. Geisler and Harden (2019) noted that, given a choice between receiving a certain amount of the same security in either a TDA or directly held appreciated assets, the heir prefers the directly held appreciated assets, as their basis is stepped-up to fair market value generally on the date of death. As a result, the heir pays tax only on any post-inheritance appreciation on the inherited assets.

The current analysis could be extended to consider such a bequest motive, but it would require also specifying several aspects of the heir’s tax situation. For example, assets left to an heir through a TDA would eventually be taxed at the heir’s ordinary tax rate, but they can be left tax-free to an heir through a TEA. Unlike prior to 2020, a non-spouse heir generally must withdraw all amounts from an inherited TDA or TEA within 10 years.20 This change from the pre-SECURE Act “stretch” rules reduces the benefit of leaving a TDA or TEA to an heir by shortening the time the assets in them can grow at a pre-tax rate of return and by shortening the deferral of taxes for a TDA. However, the decision whether to leave assets to an heir through taxable accounts, TDAs, or TEAs affects the decumulation decision because assets left to an heir cannot also be decumulated during the client’s lifetime.

Many clients are married, and the tax brackets and IRMAA bumps they face will change upon the first of their deaths. The analysis here does not incorporate this consideration but instead highlights and illustrates the benefits of carefully navigating various tax considerations that are present, regardless of marital status.

Conclusions and Implications

As can be seen from these cases, a financial planner can provide value to clients by identifying client-focused decumulation strategies that are more tax-efficient than the Conventional Wisdom and Schwab strategies. These alternative strategies include taking advantage of both low ordinary tax brackets and low long-term capital gains tax rates. Being conscious of the SSB tax torpedo is also important, as there is more flexibility to take advantage of these lower tax rates before the client begins to receive SSBs. Partial Roth conversions also can be taken advantage of before RMDs begin. How much should be taken out of each type of account every year to both properly manage income taxes during retirement years and also generate the needed after-tax cash flow is an overwhelming task for most clients and they are looking for their financial planner to lead them through this annual decision.

With Case A’s nest egg of $800,000 (Figure 1), the most tax-efficient strategy was to fill up the 12 percent statutory tax bracket within the first five years (i.e., before starting SSBs at age 70). After that, TDA withdrawals are taken to put taxable income at the top of the 27.75 percent effective tax rate bracket and avoid the 46.25 percent effective tax rate bracket every year after SSBs began, while providing the after-tax cash needed.

One feature of strategies that works well in all three cases is accelerating income before SSBs begin. If the nest egg is moderate enough (e.g., Case A), accelerating income in these earlier years to fill up the 12 percent tax bracket can be sufficient to avoid the worst part of the tax torpedo (i.e., the 46.25 percent effective rate) in later years. If the nest egg is somewhat larger (Case B), accelerating income taxed in the 22 percent rate bracket can have the same effect. If the nest egg is even larger (Case C), accelerating income taxed in the 24 percent rate bracket can save a lot of income tax in later years as well as significantly reduce additional Medicare premiums due to IRMAA bumps.

It is also critical that the financial planner examine the long-term tax impacts over the client’s entire portfolio life and not just the short-term tax effects. For example, if TEA withdrawals are reserved to the latter years of a retirement portfolio’s life, the client will enjoy a low or zero tax rate in those years, but it comes at the cost of larger TDA withdrawals that are often taxed at relatively higher rates in earlier years. The tax benefit of the former may not outweigh the tax cost of the latter. It is important to project the long-term tax consequences ensuing from a decumulation strategy, so they can be better understood for a client’s particular circumstances—consequences a financial planner is well-positioned to evaluate. As can be seen by this article’s comparison of decumulation strategies, recommending a tax-efficient one is clearly a potential high value-added service by financial planners, especially in the common situation of a retiree with multiple types of investment and retirement accounts.

Endnotes

- One could examine the probability of outliving the portfolio rather than portfolio life, but it would be a more complex analysis and would involve similar tax considerations.

- Because of this gradual increase in SSBs’ taxation as non-SSB income (plus tax-exempt interest) increases, an additional dollar of such income can cause an additional $0.00, $0.50, or $0.85 of SSBs to be included in taxable income. See Geisler and Hulse (2018) and Reichenstein and Meyer (2020) for a detailed discussion of this “tax torpedo.”

- See Public Law 115-97. The scheduled expiration of the tax cuts under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 coincides in the analysis with the client’s start of SSBs. This expiration is consistent with the higher future tax rates that many financial planners expect.

- Roth 401(k)s are subject to RMDs after reaching age 72, but Roth IRAs are not. The analysis in this article assumes that Roth 401(k)s are rolled over to a Roth IRA that was set up more than five years earlier.

- “Schwab Intelligent Income” is available with “Schwab Intelligent Portfolios Solutions.” It is designed “to automate Schwab’s best thinking on retirement income and generate a monthly paycheck from your portfolio.” Thus, these are intended to address the following issue: “When it comes to retirement income needs, it can be complex and time consuming to figure out how much you can withdraw from your investment accounts and how long your money will last.” See intelligent.schwab.com/public/intelligent/insights/whitepapers/retirement-income.html.

- Because the tax torpedo could occur in the 10 or 15 percent tax brackets (post-2025) and at a 150 or 185 percent rate, the effective marginal tax rate could instead be 15, 18.5, or 27.75 percent.

- At the time of Cook, Meyer, and Reichenstein (2015), the lowest two federal tax rate brackets were 10 and 15 percent. The analysis here uses these 10 and 15 percent tax rates for 2026 and later years but uses for 2021-2025 the 10 and 12 percent tax rates under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

- The $42,000 of annual SSBs is approximately 90 percent of the maximum SSBs for 2021, which is $3,895 per month for an individual beginning SSBs at age 70. This is consistent with a client who has a larger retirement nest egg and had higher earned income during their career.

- AGI is not high enough in Cases A and B to trigger the NIIT.

- The analysis does not consider dividend-paying stocks because doing so would cause part of the income range that otherwise would tax capital gains at a zero percent rate to be used instead for the dividends, thus, reducing the flexibility of the Harvest strategy.

- A Monte Carlo simulation could be used instead of static returns but it could confound the results by blurring the distinction between the effects of such variability and the effects of taxes. In the authors’ experience, financial planners often assume static returns for long-term plans and adjust these returns based on changes in historical experience.

- The analysis throughout this article uses real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) returns and dollars. The dollar thresholds for the taxability of SSBs and the 3.8 percent NIIT are not inflation-adjusted, so they gradually decline in real dollars year-to-year. In contrast, tax brackets, the standard deduction, and IRMAA bumps are adjusted annually for inflation, so they do not vary in real dollars year-to-year. A 2 percent inflation rate is consistent with previous work in this area, such as Geisler and Hulse (2018), and means the nominal annual returns for the stocks and bonds are approximately 8 and 4 percent. While slightly different inflation adjustments are used for various tax and SSBs purposes, those differences have minimal impact on these analyses.

- Rebalancing occurs once annually in each type of account so that differences in portfolio lives for decumulation strategies can be attributed to differing tax consequences rather than differing mixes of investments. Rebalancing inside TDAs and TEAs does not trigger income tax. Rebalancing (i.e., selling appreciated stocks and buying bonds) in taxable accounts triggers long-term capital gain income and is accounted for annually in the analysis.

- For the $36,000 of SSBs pertaining to Figure 1, the 50 percent phase-in of SSBs’ taxability occurs only with a small amount of positive taxable income from ages 70 through 76, but the effective marginal tax rate for it is not labeled because it is so small. It disappears after a few years because the thresholds for taxing SSBs gradually decline in real dollars year-to-year. Inside the SSB tax torpedo, the effective marginal tax rate for long-term capital gains can differ from that for ordinary income because the statutory rates on these two types of income differ. To avoid confusion, the figures do not depict this, but it is incorporated into portfolio lengths when appropriate.

- Portfolio lengths are not comparable across Cases A, B, and C because they involve differing after-tax cash flows. The only comparisons that are relevant in this article are the four strategies within each case.

- For the years in which long-term capital gains are harvested by gradually liquidating the taxable accounts, partial Roth conversions are made so taxable income reaches the top of the zero percent long-term capital gain tax bracket rather than the top of the 12 percent ordinary income tax bracket (i.e., $40,400 rather than $40,525). This slight difference is not perceptible in Figure 2.

- Except for the Schwab strategy, RMDs force the client in a few years to take larger TDA withdrawals than the strategy otherwise would dictate (ages 72 through 77 for Conventional Wisdom). The larger withdrawals are required from ages 72 through 73 in the Income Tax Rate-focused strategy, and ages 72 through 75 for the Avoid IRMAA Bump-focused strategy. Schwab’s proportional use of taxable accounts and TDAs cause TDA withdrawals to exceed RMDs in all years before the TDA is exhausted.

- IRMAA is generally based on AGI for the second-previous year, and the analysis incorporates this. For the first two years of retirement, the individual is assumed to have filed Form SSA-44 because of the life-changing event of stopping work and, thus, can use current year AGI to determine IRMAA for Case C. In Cases A and B, for all four strategies, there is no IRMAA the first two years.

- The two client-focused strategies do not produce any NIIT.

- This applies for inheritances beginning in 2020. Prior to the SECURE Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-94), heirs could liquidate the account within either five years or over the heir’s life expectancy. This provided an opportunity to increase the balance in a TEA over the heir’s life if the heir was young enough at the time of inheritance. The SECURE Act eliminated the life expectancy option for most heirs.

References

Bengan, William P. 1994. “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data.” Journal of Financial Planning 7 (4): 171–180.

Cook, Kirsten A., William Meyer, and William Reichenstein. 2015. “Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategies.” Financial Analysts Journal 71 (2): 16–29.

Coopersmith, Lewis W., and Alan R. Sumutka, 2011. “Tax-Efficient Retirement Withdrawal Planning Using a Linear Programming Model.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (9): 50–59.

Fullmer, Richard K. 2007. “Modern Portfolio Decumulation: A New Strategy for Managing Retirement Income.” Journal of Financial Planning 20 (8): 40–51.

Geisler, Greg, and Bill Harden. 2019. “Should Charitable Taxpayers Donate Directly from an IRA or Donate Appreciated Securities?” Journal of Financial Planning 32 (12): 46–56.

Geisler, Greg, and David S. Hulse. 2018. “The Effects of Social Security Benefits and RMDs on Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategies.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (2): 36–47.

Guyton, Jonathan T. 2004. “Decision Rules and Portfolio Management for Retirees: Is the ‘Safe’ Initial Withdrawal Rate Too Safe?” Journal of Financial Planning 17 (10): 54–62.

Horan, Stephen M. 2006a. “Withdrawal Location with Progressive Tax Rates.” Financial Analysts Journal 62 (6) 77–87.

Horan, Stephen M. 2006b. “Optimal Withdrawal Strategies for Retirees with Multiple Savings Accounts.” Journal of Financial Planning 19 (11): 62–75.

Jennings, William W., Stephen M. Horan, William Reichenstein, and Jean L.P. Brunel. 2011. “Perspectives from the Literature of Private Wealth Management.” The Journal of Wealth Management 14 (1): 8–40.

Kitces, Michael. 2019a. “Navigating the Capital Gains Bump Zone: When Ordinary Income Crowds Out Favorable Capital Gains Rates.” Available at www.kitces.com/blog/long-term-capital-gains-bump-zone-higher-marginal-tax-rate-phase-in-0-rate/.

Kitces, Michael. 2019b. “The Importance of Finding Your Tax Equilibrium Rate for Retirement Liquidations.” Available at www.kitces.com/blog/tax-rate-equilibrium-for-retirement-taxable-income-liquidations-roth-conversions/.

Kitces, Michael. 2020. “Navigating Income Harvesting Strategies: Harvesting (0%) Capital Gains Vs. Partial Roth Conversions.” Available at www.kitces.com/blog/navigating-income-harvesting-strategies-harvesting-0-capital-gains-vs-partial-roth-conversions/.

Pfau, Wade D. 2011. “Safe Savings Rates: A New Approach to Retirement Planning Over the Life Cycle.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (5): 42–50.

Reichenstein, William R. 2006. “Withdrawal Strategies to Make Your Nest Egg Last Longer.” AAII Journal 28 (10): 5–11.

Reichenstein, William. 2019. Income Strategies: How to Create a Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategy. Leawood, KS: Retiree Inc.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2020. “Using Roth Conversions to Add Value to Higher-Income Retirees’ Financial Portfolios.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (2): 46–55.

Sumutka, Alan R., Andrew M. Sumutka, and Lewis W. Coopersmith. 2012. “Tax-Efficient Retirement Withdrawal Planning Using a Comprehensive Tax Model.” Journal of Financial Planning. 25 (4): 41–52.

Welch, James S., Jr. 2015. “Mitigating the Impact of Personal Income Taxes on Retirement Savings Distributions.” Journal of Personal Finance 14 (1): 17–27.

Citation

Geisler, Greg, Bill Harden, and David S. Hulse. 2021. “A Comparison of the Tax Efficiency of Decumulation Strategies.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (3): 72–89.