Journal of Financial Planning; May 2014

According to Warren Buffett, investing is simple, but it is not easy. This eloquent sentence captures the complexities financial advisers and clients face in identifying and implementing an appropriate investment strategy. The components of behavioral economics hold promise in classifying and explaining these complexities. These complexities often take predictable forms known as biases. Many of these biases relate to how individual investors perceive risk and act in the face of risk.

During the onboarding process, clients will provide valuable information that the financial adviser needs to use to determine risk tolerance. The financial adviser needs to be discerning, as this valuable information will not directly come from the standard risk tolerance questionnaire—its source is effective communication with the client.

For example, some questionnaires have a very limited number of questions, and that increases the possibility that a change in any given answer can skew the final outcome. Furthermore, poorly worded questions loaded with jargon, or questions that do not consider the impact demographics can have on risk tolerance, could raise the problem of validity. For more on these topics, see Yook and Everett (2003) and Roszkowski, Davey, and Grable (2005). Both articles were early in highlighting problems with conventional risk tolerance questionnaires.

This article shows how behavioral finance issues and investor psychology could lead to poor decision-making. It inspects the flaws contained in typical risk tolerance questionnaires. It then examines ways to improve on these questionnaires by proposing a framework that allows for asking and answering client-specific questions. In the process, this will enhance the adviser-client relationship while improving the client investing experience.

Understanding and Improving Affective Forecasting

How many questions are on your risk tolerance questionnaire? Do the questions really categorize clients appropriately? The standard questionnaires ask too few questions and ask the wrong types of questions. The biggest problem is that, frankly, people stink at affective forecasting—trying to guess now how they will feel (what psychologists call “affect”) in the future. As a result, individual investors do not handle portfolio losses ex post (after they happen) as well as they thought they would ex ante (beforehand, when the losses were hypothetical).

Psychologists have known for a long time, and research regularly confirms, that people often make affective forecasting errors (Gilbert and Wilson 2007).

When making affective forecasts, people mentally simulate a future situation (for example, imagining playing a slot machine in a casino) and assume that that’s how they will feel when actually in that situation. “Prospections” is the name given to these mental simulations. There are many problems with making prospections, but the four main ones are:

Unrepresentative: Mental simulations are constructed from memories of past events that do not necessarily reflect how future events will unfold. People tend to remember only the extremes. A negativity bias means people are more sensitive to negative events than to positive ones.

Essentialized: Mental simulations only contain the main features of the event, not the minor details.

Abbreviated: Mental simulations are necessarily shorter than the actual event. Abbreviated prospections generally contain representations of only the earliest moments of the event.

Decontextualized: Contextual factors that are present at the time an individual mentally simulates a future event may not be present at the time the event actually occurs.

Often, people are in “cold” emotional states when doing the imagining, and they find it difficult to simulate the “hot” emotional state they will be in when the event occurs (Gilbert, Gill, and Wilson 2002).

To add to the problem, individual investors fail to perceive the extent of their forecasting error, so they do not learn from past forecasting errors and fail to adjust subsequent forecasts. Misprediction and misremember seem to go hand-in-hand. People have a tendency to anchor on their current affective state when trying to recall their previous affective forecasts.

Reminding people of their actual forecasts enhances learning. The same investor completing an investment risk questionnaire would presumably have a much greater tolerance for downside losses in March 2005 than he would in March 2009. Thus, it may be useful to complete a risk tolerance questionnaire periodically to track not only changes in risk perceptions and tolerance, but to identify whether extant market conditions affect the answers.

One way to improve affective forecasting is to experience a wider range of actual outcomes. Individual investors with more investing experience are likely to be better at gauging how they will feel if they actually lived through similar market events in the past. Here, it is not just the number of years of investing experience that matters, but which specific years were actually experienced. If the risk tolerance questionnaire does not ask about investing experience, including identification of market participation during actual periods of market turmoil, the financial adviser should be skeptical of the reliability of the answers given.

Lack of Commitment and Best-Case Planning

Do you know someone who is always late? This person may be regularly committing the planning fallacy. Individuals often underestimate how long it will take to complete projects, even if the estimate of similar projects has proven unrealistic in the past. This stems from the mental construction of unrealistic scenarios used to foresee how a project would unfold. Initially, those mentally constructed scenarios are often optimistic, best-case scenarios that fail to include any unexpected problems that may arise during the project.

People tend to disregard the negative possibilities as unlikely to happen to them. Subsequently, individuals grossly overestimate the intensity and duration of their negative affect after failure and only slightly overestimate the intensity and duration of their positive affect after success. In other words, failure feels really bad, and success only feels pretty good. A person may feel bad about always being late, but the positive reward of being on time pales in comparison. Learning depends not on negative reinforcement, but on positive reinforcement.

Adherence to a rational investment plan is often required to achieve a long-term financial goal. Short-term experiences, diversions, unexpected events, and anxiety get in the way and impede progress. Regrettably, deviations from the plan often occur at unfortunate times as investors get scared and sell when the market is down. Investors follow the herd when it is too late.

Although people would likely be more satisfied with the result of an unchangeable decision, they tend to prefer making changeable decisions. This means that going beyond the risk tolerance questionnaire, a financial plan must be more of a “financial strategy.” This may mean taking historical returns and shaving a few percentage points to build in a buffer. This likely will result in saving more than is needed, but that is better than falling short when you recall that failure feels really bad, and success only feels pretty good.

After-the-Fact Rationalization

People have a special talent for restructuring their views of outcomes. Oftentimes, people cast a positive light on actual outcomes. In elections, people recognize the strength of the candidates they opposed once those candidates win the election. Human beings are famous for seeking, attending to, interpreting, and remembering information in ways that allow them to feel satisfied with themselves and their situations. Social psychologists study these under a variety of rubrics—dissonance reduction, self-deception, ego defense, positive illusion, emotion-based coping, self-affirmation, and self-serving attribution, to name a few. The tendency of subjective optimization of outcomes is a type of psychological immune system that protects us from the emotional consequences of suboptimal outcomes.

Because people fail to anticipate the operation of the psychological immune system, people may inadvertently take actions that impair its operation and thereby jeopardize their prospects for satisfaction. The economist Adam Smith said that all men eventually accommodate themselves to whatever becomes their permanent situation. People attempt to change what they prefer not to accept and then find ways to accept that which they cannot change.

This characteristic is actually a positive for the financial adviser; it suggests that the client may be more willing to “forgive” than one would initially reason, provided the initial decision was well-informed and made with explicit buy-in from the clients. Once the client “owns” the decision, he or she may “rationalize away” the actual result. Said another way, it is the process that really matters more than the results.

Intrinsic-Extrinsic Motivations

What motivates people? Conveniently, most individuals fall into an intrinsic-extrinsic motivation spectrum. Extrinsic individuals tend to believe that extrinsic goals, such as money, fame, or image, will satisfy autonomy (self-determination) and competence needs. These people tend to overestimate the emotional benefits of achieving extrinsic goals to their potential detriment.

An intrinsic individual—who tends to seek personal growth, intimacy, or community—tends not to overestimate the emotional benefits of achieving extrinsic goals. A financial adviser can better manage a relationship with an individual investor when the adviser knows if the client is extrinsically or intrinsically motivated. An extrinsically motivated client may need more frequent communication about current market conditions than a client who is intrinsically motivated. Although each client may ultimately have the same portfolio, the communication strategy used with each will likely be very different.

Building More Effective Questionnaires

This section addresses flaws in investor questionnaires and proposes some solutions.

Age, retirement, and sources of income. A notable challenge with a typical investor risk questionnaire is asking questions in a vacuum. It might ask an investor’s age, but not when the investor plans to retire, or vice versa. The financial adviser needs to understand both components along with expected sources of income upon retirement.

For example, suppose an individual investor is seeking to retire early, at age 50. In this instance, it would be important to understand expected sources of income. If a 401(k) plan is a possible income source, the account may be subject to a 10 percent penalty on money withdrawn before age 59½. Now consider another client whose expected retirement age is 62. This client expects to supplement an IRA with Social Security when she turns 62. With that information, an adviser is in a position to discuss whether it is optimal to take Social Security immediately or postpone benefits, increasing future benefits.

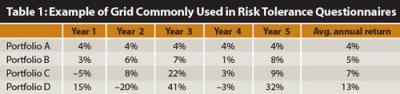

Percentages versus dollar amounts. Questionnaires commonly ascertain risk tolerance by using a grid with hypothetical portfolios and calendar year returns. Typically, one scenario has small deviations, one has wide deviations, and a handful are somewhere in between. Such a grid might look like Table 1.

The intention is for individual investors to select a portfolio that matches their risk tolerance. A flaw is returns are typically represented using percentages, not dollars. Consider a client with $1 million who indicates having a high-risk tolerance. If shown return percentages of down 5 percent, up 10 percent, down 20 percent, and up 15 percent, the client may select this hypothetical portfolio. However, would a different result occur if the client saw the dollar amounts (down $50,000, up $100,000, down $200,000, and up $150,000)?

One proposal is to create a modular grid that uses each client’s assets as inputs to create a hypothetical portfolio that auto-populates with dollar amounts corresponding to a range of percentage gains or losses. This allows equal treatment for clients with large and small account balances. For example, a $10,000 loss might not mean as much to a $1 million client as it would to a client with $50,000.

What are you saving for? Questions about time horizon, including when planned withdrawals are to commence, are often contained in questionnaires. What these questions miss is the individual’s intent—that is, what does the client plan to do with the money? Asking this aids in portfolio construction and helps an adviser construct a communication plan. It could be as simple as the following question:

How do you expect to spend your investments in retirement (select as many as relevant)?

- Living expenses (mortgage, rent, food, etc.)

Donations

Family activities

New house, car, or boat

Travel

Golf, tennis, etc. club

Other_____________

It is also important to rank the answers in order of importance, because this can help an adviser determine where a client falls on the extrinsic-intrinsic motivation scale. It can help an adviser learn more about the client’s values and goals, and knowing the competing goals and their ranking of importance will help in building a portfolio and the communication plan.

Timing is everything. Risk tolerance tends to be procyclical. Tolerance for risk increases when markets rise and decreases when markets fall (Bateman et. al 2011; Pan and Statman 2012). This is why, when filling out questionnaires, timing is everything. Recent events often skew an investor’s stated risk tolerance. Priming and preparing the client could help. The financial adviser could consider asking one set of questions after a strong market experience and a different series of questions after a weak market experience.

For example, after a strong market: “We recently experienced a strong market. However, were you aware that in 2008 the S&P 500 lost 37 percent? Would this bother you?”

After a weak market: “Returns have been poor lately. However, were you aware that in 2009 the S&P 500 was up 28 percent? Although past performance is no guarantee of future results, positive returns can happen again.”

Emotions are not constant. To strengthen the adviser-client relationship and improve the client’s investing experience, financial advisers should periodically review and update questionnaires. It may be beneficial to test a client’s responses at different points in the cycle, because emotions are not constant. Conceptualize a “you today” and a “you tomorrow.” How can advisers protect the “you tomorrow” from the “you today”? Because emotions are integral to investing, remember that questionnaires are a point-in-time measure of risk tolerance. Initial questionnaires are the starting point, not the ending. Be aware emotions and markets change, and future responses are opportunities to expand relationships.

Trust, knowledge, and skill. Trust has major implications for risk tolerance. Individual investors with a low level of trust may be more likely to sell after a market panic rather than trust the long-term plan. Because of this, and because trust is often associated with comfort, investors with a higher level of trust may have a higher risk tolerance. More trust means a higher likelihood of sticking with the plan.

Trust and knowledge can go hand-in-hand. Some clients think about investments once per year in a meeting with their adviser, while others absorb (perhaps too much) information, actively researching investments. It is important to learn how often a client thinks about his or her finances, what sources of information the client uses, and how frequently he or she uses those various sources.

The risk tolerance questionnaire should ask questions, perhaps in a quiz-like format, to help clients calibrate the level of familiarity they have of the financial markets and investments. Like trust, clients with more understanding may be better equipped to handle volatility. Perhaps risk tolerance questionnaires and client communications need to contain factoids that buck the conventional wisdom. Yes, advisers are supposed to be the investing experts, but clients need to know enough to trust the experts. It is usually because of a lack of knowledge that people do not trust experts.

A related concept is skill. A typical risk questionnaire asks investors to estimate their level of skill in relation to the average investor. The ranking is subjective, and self-ranking of skill is problematic. There is often a gap between perceived and actual skill, and moderate knowledge sometimes results in overconfidence. Instead of relying on subjective responses, a better approach may be to ask clients to analyze historical investment decisions and consider actions they took in specific market environments or specific personal situations.

People often fail to perceive the extent of their forecasting errors by misremembering. Most good portfolio managers keep a journal, documenting their ideas, forecasts, and rationales for investments. But documenting these things is only part of the process; revisiting the journal is also essential. For example, if a client asks about investing in gold, it is good to record that and remind the client of the rationale (if any) given at the time. Has the client asked similar questions in other situations? What were the actions taken then and the consequent results? Reminding clients of these things enhances learning and can help build the adviser-client relationship.

Determine the level of control. Some people like to drive; others prefer to be driven. The same concept exists in investing. Some clients will not feel comfortable unless they are in complete control, at all times. Others prefer to have their portfolio professionally managed, finding comfort in not having to make decisions.

Without trust, a client is unlikely to give up control; with it, the client may have a good partnership with the adviser, but still want to maintain control. The financial adviser should ask questions that indicate the level of control desired, or even ask directly which approach the client prefers. Knowing the level of control or delegation desired from the beginning can help avoid bad decisions in crises and foster better communication. As trust grows, delegation may increase as well.

Trading and performance. Does the client care about performance relative to a market benchmark, or is the benchmark their peers? To some clients, relative performance is quite important. All else being equal, individual investors do not prefer underperforming investments, even if those investments are proper choices for their goals and situation. However, all else seldom is equal.

At times, individual investors are willing to trade relative performance for lower volatility. Other investors may place a greater emphasis on relative performance. Investment policy statements will always state a benchmark. Remind the client of the benchmark. Remind the client why the benchmark is important. However, be willing to change the benchmark if the client’s preferences or situation changes.

Use the Questionnaire to Deepen the Adviser-Client Relationship

Assessing client risk tolerance is a large and complex task. Whatever risk tolerance questionnaire is available, the financial adviser must use it as a tool to help the client, while embracing the realities of psychology. Proper development and ongoing use can deepen the adviser-client relationship.

The financial adviser could use a risk tolerance questionnaire as a part of a communication plan for each client. Tailored communication can enhance trust, and clients with a higher level of trust in the adviser are more open to guidance and more open to participating in frank discussions about needs and concerns. This custom communication plan is probably more important than a customized portfolio.

References

Bateman, Hazel, Towhidul Islam, Jordan Louviere, Stephen Satchell, and Susan Thorp. 2011. “Retirement Investor Risk Tolerance in Tranquil and Crisis Periods: Experimental Survey Evidence,” Journal of Behavioral Finance 12 (4): 201–218.

Gilbert, Daniel T., Michael J. Gill, and Timothy D. Wilson. 2002. “The Future Is Now: Temporal Correction in Affective Forecasting.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 88 (1): 430–444.

Gilbert, Daniel T., and Timothy D. Wilson. 2007. “Prospection: Experiencing the Future.” Science 317 (5843): 1,351–1,354.

Pan, Carrie H., and Meir Statman. 2012. “Questionnaires of Risk Tolerance, Regret, Overconfidence and Other Investor Propensities.” Journal of Investment Consulting 13 (1): 54–63.

Roszkowski, Michael J., Geoff Davey, and John E. Grable. 2005. “Insights from Psychology and Psychometrics on Measuring Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Financial Planning 18 (4) 66–78.

Yook, Ken C., and Robert Everett. 2003. “Assessing Risk Tolerance: Questioning the Questionnaire Method.” Journal of Financial Planning 16 (8) 48–55.

Brian J. Jacobsen, Ph.D., CFP®, CFA, is chief portfolio strategist at Wells Fargo Funds Management. He also serves as director of the financial planning program at Wisconsin Lutheran College where he is an associate professor.

Peter Speidel, CFA, is an investment analyst at Wells Fargo Funds Management, where he analyzes the performance of asset allocation strategies, including alternatives strategies, and performs due diligence on portfolio managers.

Travis L. Keshemberg, CFA, CIPM, CIMA, is director of research at Wells Fargo Funds Management, where he heads up the risk management committee and participates in new product development.

Ryan Hodapp, CFA, CAIA, is an investment strategies consultant at Wells Fargo Funds Distributor.