Journal of Financial Planning: May 2016

Greg Geisler, Ph.D., is an associate professor of accounting at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. He teaches a graduate course on taxes and investments. His work has been published in many journals, including the Journal of Financial Planning, Journal of Financial Service Professionals, State Tax Notes, and Tax Notes.

David S. Hulse, Ph.D., is a faculty member in the Von Allmen School of Accountancy and the Martin School of Public Policy and Administration, both at the University of Kentucky. He has published tax-related articles in several journals and is a contributing author for a federal taxation textbook.

Executive Summary

- Up to 85 percent of Social Security benefits could be taxable, with the percentage increasing as income increases.

- Additional income can cause additional Social Security benefits to be taxable, a so-called “tax torpedo.”

- The tax effect of this tax torpedo depends on the tax bracket in which the benefits are taxed. This effect can be as high as 21.25 percent of the additional income, but it is less than 10 percent in many circumstances.

- This tax effect is an important factor to consider when deciding whether to start Social Security benefits at age 62 or age 70.

Important Definitions

- Provisional income (PI) equals modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) plus one-half of the Social Security benefits (SSBs) received.

- MAGI is AGI determined without regard to the taxable portion of SSBs and without regard to certain exclusions and above-the-line deductions.

The taxability of Social Security benefits (SSBs) for federal income tax purposes phases in as income increases. None of the benefits are taxable at low levels of income, but up to 85 percent of the SSBs are taxable at higher levels of income. At intermediate levels of income, where the SSBs’ taxability is phasing in but has not reached the maximum 85 percent, additional income causes additional SSBs to be taxable, a phenomenon that has been dubbed the “tax torpedo” (see Meyer and Reichenstein 2013; Garland 2013; and VanZante and Fritzsch 2011).

The effect of the tax torpedo on one’s taxes is not necessarily large; it depends on the rate at which the SSBs’ taxability is phasing in, but it also depends on the tax bracket in which it is occurring. The first factor often receives more attention than the second one, but both factors should be considered.

This paper analyzed the joint effect of these two factors. It shows that the additional SSBs that are taxable because of an additional dollar of income generates an additional tax that ranges from zero to 21.25 cents (in addition to the tax on the additional dollar of income per se). Graphs are used to depict circumstances in which the zero, 21.25 cents, and other amounts of additional tax occur. Planning implications are also examined, including the decision to start SSBs at age 62 versus age 70. Surprisingly, there are situations where an individual is better off taking SSBs in a way that triggers the tax torpedo; the reason is that the tax effect of the tax torpedo depends on the tax bracket in which it is occurring. The analysis here can be used by financial planners to better understand the tax effect of the tax torpedo and better plan for it.1

This analysis differs in several ways from previous articles examining the tax torpedo and its effect on the decision to accelerate or delay the start of SSBs. First, this analysis takes into account the individual’s before-tax income throughout retirement and not just the years of ages 62 and 70. Second, a wider variety of circumstances were examined to show that the tax torpedo could make it advantageous, disadvantageous, or have a neutral effect on this decision.

The relevant tax law regarding SSBs’ taxation and graphs illustrating it are also presented. Next, the tax law’s tax brackets are discussed, and graphs illustrating them are presented in conjunction with the graphs for SSBs’ taxation. Planning implications for the decision to start SSBs at age 62 versus age 70 are then examined. Finally, other planning implications are discussed, and conclusions are drawn.

Relevant Tax Law

The portion of SSBs that are taxable depends in part on an amount referred to as provisional income (PI). PI equals modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) plus one-half of the SSBs received. MAGI is adjusted gross income determined without regard to the taxable portion of SSBs and without regard to certain exclusions (such as tax-exempt interest) and above-the-line deductions (such as interest paid on education loans) (IRC Sec. 86(b)(2)).

For a married couple filing jointly, none of their SSBs are taxable if PI is less than $32,000. If their PI is more than $32,000 but less than $44,000, the taxable portion of their SSBs is the lesser of (a) one-half of the SSBs; and (b) one-half of their PI exceeding $32,000. This means that some, but no more than one-half, of their SSBs are taxable. If their PI is more than $44,000, the taxable portion of their SSBs is the sum of (c) 85 percent of their PI exceeding $44,000; and (d) the lesser of $6,000 or one-half of the SSBs. However, if this sum is more than 85 percent of the benefits, only 85 percent of the SSBs are taxable (IRC Sec. 86(a) and (c)).

For individuals whose filing status is single, head of household, or qualifying widow(er), the taxable portion of SSBs is determined in the same manner as for a married couple filing jointly, except the first PI threshold is $25,000 instead of $32,000, the second PI threshold is $34,000 instead of $44,000 (IRC Sec. 86(c)), and the dollar amount in item (d) is $4,500 instead of $6,000.²

It is interesting to note that, unlike many other dollar amounts in the tax law, the first PI thresholds of $32,000 and $25,000 have not been adjusted for inflation since they first applied to individuals in 1984. Had they been so adjusted, they currently would be approximately $72,000 and $56,000.

Graphs of Taxable Portion of Social Security Benefits

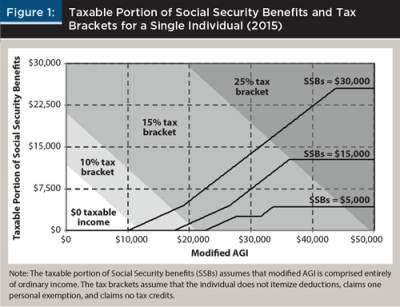

The analysis focused first on the extent to which SSBs are taxed. The solid lines in Figure 1 depict the taxability for a single individual for three SSB amounts: $5,000, $15,000, and $30,000 (the shading in Figure 1, that is, tax brackets, is discussed in the next section). For example, if MAGI is $40,000 and SSBs are $30,000, approximately $22,500 of the SSBs are taxable.

Recall that PI equals MAGI plus one-half of SSBs and that the two PI thresholds for single individuals are $25,000 and $34,000. When the SSBs are $30,000, this means that some of them will be taxable when MAGI exceeds $10,000, because MAGI plus one-half of $30,000 will exceed $25,000. As MAGI increases beyond $10,000, the taxable portion of SSBs increases by 50 cents for each additional $1 of MAGI, because their taxability is phasing in at a 50 percent rate. This occurs until MAGI is $19,000, when the second PI threshold of $34,000 is reached. Beyond that threshold, each additional $1 of MAGI causes another 85 cents of SSBs to be taxable, but this

85 percent phase-in continues only until 85 percent of the SSBs are taxable. This 85 percent maximum is reached at $43,706 of MAGI, beyond which no additional SSBs are taxed.

Note that when a single individual’s SSBs are $30,000, the tax torpedo arises when MAGI is between $10,000 and $43,706. Single individuals whose earnings history produces $30,000 of SSBs often will have MAGI exceeding $43,706, typically because of investment earnings and taxable distributions from retirement accounts, so 85 percent of their SSBs will be taxable regardless of their planning decisions.

The line in Figure 1 when SSBs are $15,000 is similar to the line when they are $30,000, although the MAGI range over which the SSBs’ taxation phases in is narrower, because there are fewer SSBs to phase in. The line when SSBs are $5,000 differs from the two other lines in that the 50 percent phase-in ends before the 85 percent phase-in begins. Thus, there are two relatively narrow MAGI ranges in which the tax torpedo occurs, as well as a narrow range between them in which there is no tax torpedo.

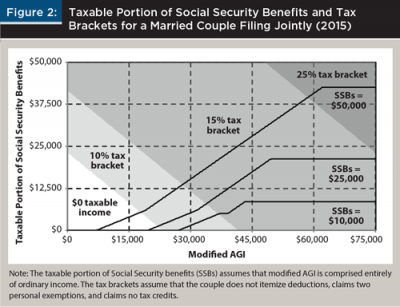

Figure 2 depicts the taxable portion of SSBs for a married couple filing jointly for three SSB amounts: $10,000, $25,000, and $50,000. The three lines are shaped similarly to those in Figure 1, although the MAGI ranges over which the 50 percent and 85 percent phase-ins occur differ because the PI thresholds for married couples filing jointly ($32,000 and $44,000) differ from those for single individuals ($25,000 and $34,000), and because the SSB amounts differ.

Overlap of Taxable Social Security Benefits with Tax Brackets

Returning to Figure 1, the three shaded areas depict combinations of MAGI and the taxable portion of SSBs that result in taxable incomes that fall in the 10, 15, and 25 percent tax brackets for a single individual in 2015.³

The unshaded area depicts such combinations that result in zero taxable income. For example, suppose the individual’s MAGI is $25,000 and SSBs are $30,000. The point in Figure 1 on the $30,000 SSBs line when MAGI is $25,000 is approximately in the middle of the 15 percent tax bracket and occurs when the SSBs’ taxation is phasing in at an 85 percent rate.

The overlap of the SSBs’ taxation with the tax brackets makes it easier to see the tax effect of the tax torpedo. In the previous example, the SSBs’ taxation, at the margin, are phasing in at an 85 percent rate and in the 15 percent tax bracket. An additional $1 of ordinary income by itself would increase taxes by 15 cents. It also would cause an additional 85 cents of SSBs to be taxable, which would further increase taxes by 12.75 cents ($0.85 × 15 percent). In total, taxes would increase by 27.75 cents.

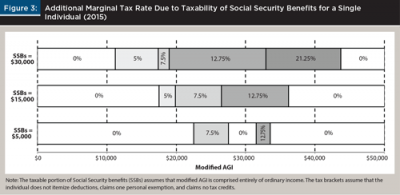

Figure 3 depicts this joint effect for the same circumstances as in Figure 1. It quantifies the tax effect of the tax torpedo as a percentage of the additional MAGI that heightens the tax torpedo. In this example, the tax effect is 12.75 percent.

When SSBs are $30,000, the tax torpedo is zero when MAGI is less than $11,233 because none of the SSBs are taxed, or because there is zero taxable income even if some of them are taxed. When MAGI is greater than $43,706, there is no tax torpedo, because 85 percent of the SSBs are taxed regardless of MAGI. Between $11,233 and $43,706 of MAGI, the tax torpedo’s tax effect ranges from 5 percent to 21.25 percent.

From $11,233 to $17,383 of MAGI, the SSBs’ taxation is phasing in at a 50 percent rate and taxable income is in the 10 percent bracket, so the additional marginal tax rate (MTR) is 5 percent. If MAGI is between $17,383 and $19,000, the additional tax rate is 7.5 percent, reflecting a 50 percent phase-in rate and a 15 percent tax bracket. The SSBs’ taxation begins to phase in at an 85 percent rate when MAGI exceeds $19,000. This occurs through the rest of the 15 percent tax bracket and into the 25 percent tax bracket, making the additional MTRs 12.75 percent and 21.25 percent, respectively.

Similar results can be seen in Figure 3 when the SSBs are $15,000, although the MAGI range over which the tax torpedo occurs is narrower due to the SSBs’ smaller size. Their 85 percent phase-in, however, is complete before the 25 percent tax bracket is reached, so the 21.25 percent rate does not occur. When the SSBs are $5,000, their phase-in occurs entirely within the 15 percent tax bracket, so the tax torpedo is 7.5 percent when it is phasing in at a 50 percent rate, and 12.75 percent when it is phasing in at an 85 percent rate.

Similar to Figure 1, Figure 2 depicts the overlap of a married couple’s tax brackets with their SSBs’ taxability.4 Compared to a single individual, less of the phase-in of the SSBs’ taxation occurs in the 25 percent tax bracket. This means that a 21.25 percent tax torpedo occurs over a narrower fraction of MAGI, an outcome that can be observed in Figure 4. The 21.25 percent rate occurs only between approximately $58,000 and $62,000 of MAGI when SSBs are $50,000, and not at all when SSBs are $25,000 or $10,000.5

Planning Implications for the Start of Social Security Benefits

The taxation of SSBs has implications for several planning decisions, including the decision to start SSBs at age 62 versus age 70. Currently, an individual’s full retirement age for SSB purposes is 66. However, an individual who delays the start of his or her SSBs until age 70 receives SSBs that are 132 percent of those that would be received if they started at age 66. An individual could instead choose to start his or her SSBs at age 62, but they would be only 75 percent of those that would be received if they started at age 66 (full retirement age is 66 years and 0 months for individuals born between 1943 and 1954) (SSA 2015). Thus, SSBs are 76 percent larger (1.32 ÷ 0.75) when they start at age 70 than when they start at age 62.

To explore the implications of SSBs’ taxation on this decision, consider a 62-year-old single individual who will receive $24,000 of SSBs if they start now, or $42,240 (76 percent larger) if they start eight years from now at age 70. Assume that the individual expects to live another 25 years and is indifferent between these choices on a pre-tax basis.6 The present value of $24,000 for 25 years equals the present value of $42,240 for the ninth through 25th years if the discount rate is 3.96 percent. Assume also that the individual has a tax-deferred retirement account (hereafter, 401(k)) and that he or she will receive distributions from it so that pre-tax income (distributions plus SSBs) are the same each year for 25 years.

Because the analysis is structured so that the individual is indifferent on a pre-tax basis, the decision will be driven solely by the tax consequences. This implies that the 401(k) has an annual before-tax return of 3.96 percent, which is the same as the discount rate that equates the present values of the $24,000 and $42,240 SSB streams. A 0 percent inflation rate is assumed for this analysis to make it easier to see how the 62-versus-70 decision is affected by the SSBs’ taxation, but it is later extended to consider a 2 percent inflation rate. Three cases (lower, middle, and higher income) are considered that differ in the magnitude of the 401(k) distributions.

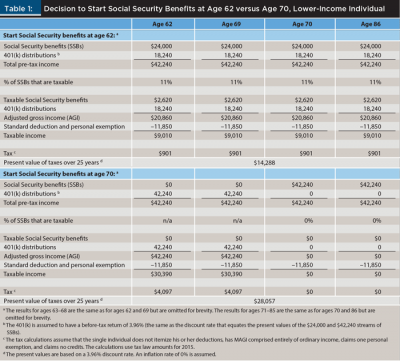

Lower-income individual. Table 1 reports the results for this case. The 401(k)’s current balance is $289,245. Given its 3.96 percent return, this can fund distributions of $18,240 per year for the next 25 years, or distributions of $42,240 for the next eight years. If the individual starts SSBs at age 62, he or she will take $18,240 of 401(k) distributions and have total pre-tax income of $42,240 (SSBs of $24,000 + $18,240). If the individual starts SSBs at age 70, he or she will take $42,240 of 401(k) distributions each year before age 70 and will have $42,240 from SSBs for age 70 and later. Therefore, the individual’s pre-tax income is $42,240 every year whether SSBs start at age 62 or age 70, although its composition differs.

If the individual starts SSBs at age 62, 11 percent of them will be taxable, while none of the SSBs are taxable if they start at age 70.7 The tax torpedo thus causes more of the SSBs to be taxable if they start at age 62. However, the tax consequences are more severe if the SSBs start at age 70, even though the tax torpedo does not occur (i.e., the present value of the income taxes over 25 years is $28,057, versus only $14,288 if SSBs start at age 62).8

To understand this counterintuitive result, note that the individual’s adjusted gross income (AGI) in those years from ages 70 through 86 will be zero if SSBs start at age 70, so his or her standard deduction and personal exemption will go unused. In addition, if SSBs start at age 70, the individual receives 401(k) distributions in the eight years before age 70 that are fully taxable and fall partially in the 15 percent tax bracket (versus, if SSBs were to start at age 62, smaller taxable distributions plus SSBs that are only 11 percent taxable and that fall entirely within the 10 percent tax bracket). In this case, it is better to start SSBs early—at age 62. Although the tax torpedo occurs, its impact is mitigated because some of it is offset by the standard deduction and personal exemption, and some of it is taxed at only a 10 percent rate. This case thus represents situations with lower-income individuals where it is often not best to avoid the tax torpedo.

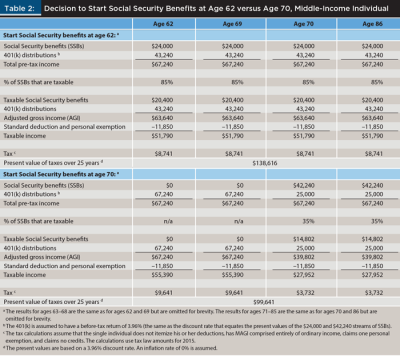

Middle-income individual. Table 2 reports the results for this case. The 401(k)’s current balance can fund distributions that are $25,000 larger than in the lower-income case—that is, $43,240 per year for the next 25 years if SSBs start at age 62 or, if SSBs start at age 70, $67,240 for the first eight years and $25,000 for the last 17 years.9 The individual’s pre-tax income is $67,240 whether SSBs start at age 62 or age 70.

In the middle-income case, the present value of the next 25 years of taxes is $138,616 if SSBs start at age 62, but only $99,641 if SSBs start at age 70. The individual incurs the maximum 85 percent taxation of SSBs when starting them at age 62, but only 35 percent of the SSBs are taxable when they start at age 70.10

In addition, the tax rate bracket in which the taxable SSBs are taxed differs for the two starting ages. When SSBs start at age 62, the 85 percent of SSBs that are taxable are taxed partially at 15 percent, and partially at 25 percent.11 In contrast, when SSBs start at age 70, the 35 percent of SSBs that are taxable are taxed only at 15 percent. In this case, it is better to delay the start of SSBs until age 70, which differs from the outcome in the lower-income case.

The middle-income case represents the classic situation where delaying SSBs is beneficial from a tax perspective; that is, where the maximum 85 percent taxability occurs if SSBs begin at age 62 but a much lower percentage of them are taxed if they begin at age 70. One reason for this outcome is that because of the substantially higher SSBs starting at age 70, much lower taxable distributions are needed to produce the desired pre-tax income, triggering less of a tax torpedo. In addition, the taxable distributions are sufficiently large to use all of the individual’s standard deduction and personal exemption regardless of the start of his or her SSBs.

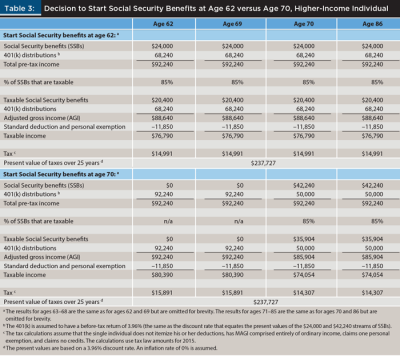

Higher-income individual. Table 3 reports the results for this case. The 401(k)’s current balance can fund distributions that are $50,000 larger than in the lower-income case (and $25,000 larger than in the middle-income case); that is $68,240 per year for the next 25 years, or $92,240 for the next eight years and $50,000 for the last 17 years.12

In the higher-income case, the present value of the next 25 years of taxes is $237,727 whether SSBs start at age 62 or at age 70. The individual incurs the maximum 85 percent taxation of SSBs with both starting ages, and the taxable portion of the SSBs falls entirely in the 25 percent tax bracket in both cases.13 This case represents a common situation for higher-income individuals: 85 percent of SSBs are taxed whether they begin early (at age 62) or late (at age 70), so there is no tax advantage or disadvantage to delaying SSBs.

Extension of cases to consider inflation. The previous cases assume 0 percent inflation in order to better highlight tax considerations, but SSBs, the standard deduction, the personal exemption amount, and the tax rate schedule are adjusted each year for inflation. However, the dollar thresholds for determining the taxable portion of SSBs ($25,000, $32,000, $34,000, and $44,000) are not adjusted each year for inflation. This means that the taxable percentage of SSBs can increase each year. Although such an increase is relatively small for any particular year, it can cumulate to a substantial effect over 25 years.

The analysis is extended by considering a 2 percent inflation rate (the Federal Reserve aims for a 2 percent inflation rate over time). This increases by two percentage points (to 5.96 percent) the discount rate at which the individual is indifferent between receiving $24,000 of inflation-adjusted SSBs starting at age 62, versus 76 percent larger inflation-adjusted SSBs starting at age 70. To further keep the individual indifferent between starting SSBs at age 62 versus age 70 on a pre-tax basis, the 401(k)’s return is also increased to 5.96 percent and the distributions from it are increased by 2 percent each year.

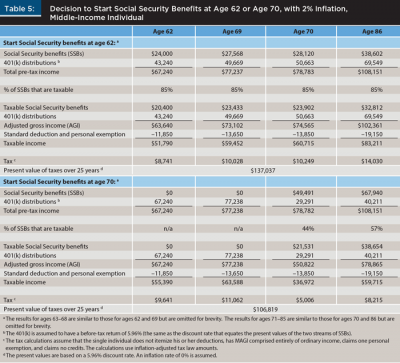

Tables 4, 5, and 6 report the results of this analysis and are qualitatively similar to the results reported in Tables 1, 2, and 3. In the lower-income case, the present value of taxes paid over 25 years is $21,291 if SSBs start at age 62, and is $27,740 if SSBs start at age 70 (see Table 4).

There is still a tax advantage to starting SSBs at age 62 rather than age 70, though its magnitude is less than when 0 percent inflation was assumed. The reasons there is still a tax advantage are the same as in Table 1: the individual does not take full advantage of the standard deduction and personal exemption when starting SSBs at age 70, and more of the individual’s income is taxed at 15 percent rather than 10 percent over the first eight years of the 25-year period when SSBs start at age 70. The fact that the dollar thresholds for determining the taxable portion of SSBs are not adjusted for inflation, however, does diminish this tax advantage. The percentage of SSBs that are taxable, if they start at age 62, increases from 11 percent at age 62 to 44 percent at age 86. The tax effect of the increasing tax torpedo over time is not as harsh as one might expect because the standard deduction, personal exemption, and tax rate schedule are adjusted for inflation every year.

In the middle-income case, where the 401(k)’s balance can fund annual inflation-adjusted distributions that are initially $25,000 larger than in the lower-income case, the results are qualitatively similar to the situation where there is 0 percent inflation (see Table 5).

Starting SSBs at age 62 results in 25 years of taxes that have a $137,037 present value versus only $106,819 when they start at age 70, so the individual is better off starting the SSBs at age 70. In the middle-income case, the maximum 85 percent of SSBs are taxable throughout the 25-year period if SSBs start at age 62, while the percentage increases from 44 percent to 57 percent if SSBs start at age 70. The fact that the SSB taxation thresholds are not indexed for inflation therefore has more of an effect when SSBs start at age 70, but the annual inflation adjustments to the standard deduction, personal exemption, and tax rate schedule mitigate the tax effects of these higher percentages of taxable SSBs.

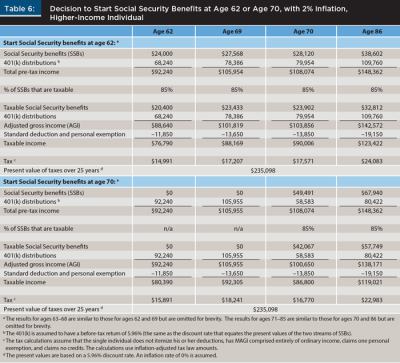

In the higher-income case, where the 401(k)’s balance can fund annual inflation-adjusted distributions that are initially $50,000 larger than in the lower-income case (and $25,000 larger than in the middle-income case), the results again are qualitatively the same as the situation where there is 0 percent inflation (see Table 6). The present value of tax payments over the 25-year period is the same $235,098 whether SSBs start at age 62 or age 70. The maximum 85 percent of SSBs are taxable regardless of the individual’s SSB timing decision.

Other Planning Implications

Recall that Figures 3 and 4 depict the additional MTR due to additional SSBs becoming taxable when there is additional MAGI. The tax on these additional taxable SSBs is in addition to the tax on the additional MAGI itself.

For example, the 21.25 percent rate occurs when the individual’s taxable income places them in the 25 percent tax bracket and the SSBs’ taxability is phasing in at an 85 percent rate. Such an individual effectively faces a 46.25 percent total MTR. Similarly, an individual in the 15 percent tax bracket faces a 12.75 percent additional tax rate and a 27.75 percent total MTR when SSBs are phasing in at an 85 percent rate. Therefore, an important planning consideration is avoiding the higher tax rates depicted in Figures 3 and 4.

Because SSBs generally are not controllable once they have begun, planning should be focused on manipulating MAGI to avoid the 21.25 percent additional MTR.14 A retiree could manipulate MAGI in several ways while maintaining his or her pre-tax cash flow. One way is to reduce taxable distributions from “traditional” retirement accounts, such as an IRA or a 401(k), and increase nontaxable distributions from Roth retirement accounts. Instead of increasing Roth account distributions, an individual could generate the needed cash inflow by liquidating investments whose sale would trigger little income. Such investments include bond funds and stocks whose basis is similar to their market value. Taking this strategy a step further, an individual could sell an investment that is worth less than its basis, generating a capital loss. For this strategy to be effective, though, the individual would have to hold the investment outside of a retirement account, and its effectiveness could be limited by the $3,000 annual limitation on an individual’s deduction of net capital losses.

An alternative strategy that can work well when MAGI is near the level at which the taxable portion of SSBs reaches 85 percent is to “bunch” taxable distributions. That is, instead of taking distributions to smooth income from year to year, an individual could take a larger-than-needed distribution in one year and a correspondingly smaller-than-needed distribution the following year (and spend the initially unneeded part of the larger distribution in the following year). To the extent that the larger distribution exceeds the threshold at which 85 percent taxability is reached, it generates no additional tax torpedo, but the smaller distribution could reduce the tax torpedo in the following year.15

If holding the initially unneeded part of the larger distribution until the following year is problematic due to insufficient financial self-control, this bunching strategy can be modified by taking a smaller-than-needed distribution in one year and increasing liabilities that year via a loan from a home equity line of credit to meet cash flow needs. In the following year, the individual could take a larger-than-needed distribution to pay back the loan.

To summarize, managing the sources of cash flow within a year and their magnitude across years to avoid the worst part of the tax torpedo as much as possible can be a worthwhile exercise for a financial planner. By doing so, the planner can significantly reduce the present value of income taxes paid by his or her client.

Conclusion

Social Security recipients and their tax advisers often are concerned that additional income will cause more of the SSBs to be taxed. While this so-called tax torpedo should not be ignored, it also should not be overemphasized. The analysis in this article examined and quantified these effects for a broad range of circumstances.

Additional income often has no effect on the taxable portion of SSBs, because their phase-in has not yet begun or is complete. In some circumstances, additional income would phase in more of the SSBs, but the tax effect of this tax torpedo would be small because the recipient’s taxable income is zero or in the 10 percent tax bracket.

In other circumstances, however, the tax effect is much larger. For example, if the SSBs’ taxation is phasing in at an 85 percent rate and taxable income is in the 25 percent tax bracket, an additional $1 of income will increase taxes by 46.25 cents: 25 cents of tax on the income per se, and 21.25 cents of tax on the additional SSBs the additional income causes to be taxed. The analysis here can help a financial planner to understand how the magnitude of this effect differs in various circumstances so as to make more effective planning decisions.

Endnotes

- The analysis is based on current laws; Social Security rules and tax laws are subject to change.

- The $25,000, $34,000, and $4,500 amounts also apply for a married individual filing separately who lives apart from his or her spouse the entire year. The three dollar amounts are $0 for a married individual filing separately who lives with his or her spouse for any part of the year.

- The analysis assumes that the single individual claims a $7,850 standard deduction rather than itemized deductions ($6,300 basic standard deduction plus one additional standard deduction of $1,550 because he or she is 65 years or older), MAGI is comprised entirely of ordinary income (no qualified dividends, long-term capital gains, or tax-exempt interest), and the individual claims one personal exemption ($4,000) and no credits.

- The tax brackets were constructed using the same assumptions as for the single individual in Figure 1, except the couple is assumed to claim two additional standard deductions and two personal exemptions.

- When SSBs are $50,000, there is a narrow range (from $17,733 to $19,000 of MAGI) where the additional marginal tax rate is 5 percent. When SSBs are $10,000, the additional rate is 7.5 percent between $36,700 and $37,000 of MAGI.

- It is acknowledged that many individuals will not be indifferent on a pre-tax basis for many reasons. Indifference is assumed to focus on and highlight tax considerations.

- If SSBs start at age 62, PI is $30,240 ((½ × $24,000) + $18,240), which is in the $25,000 to $34,000 range where the SSBs’ taxability is phasing in at a 50 percent rate. Taxable SSBs are $2,620, which is the lesser of $2,620 (½ × ($30,240 – $25,000)) or $12,000 (½ × $24,000). This $2,620 is 11 percent of the SSBs ($2,620 ÷ $24,000). If SSBs start at age 70, PI in those years is $21,120 ((½ × $42,240) + $0), which is less than the $25,000 threshold beyond which some of the SSBs are taxable. Taxable SSBs are zero.

- The analysis assumes that the individual qualifies for a $1,550 additional standard deduction starting at age 62 rather than age 65, making it easier to focus on the key drivers of the tax effect. This assumption slightly understates the tax for ages 62, 63, and 64, but it does so for both options.

- The 401(k) thus has a $685,687 balance immediately before distributions begin at age 62. As in the lower-income case, the 401(k) has a 3.96 percent pre-tax return, so its balance will reach zero after 25 years if the annual distributions are $43,240 or if annual distributions the first eight years are $67,240 and from the beginning of the ninth year through the 25th year are $25,000.

- If SSBs start at age 62, PI is $55,240 ((½ × $24,000) + $43,240), which is beyond the $34,000 threshold where the 85 percent phase-in of the SSBs’ taxability begins. Taxable SSBs are $20,400, which is the lesser of $22,554 ((.85 × ($55,240 – $34,000)) + $4,500) or $20,400 (.85 × $24,000). This $20,400 is 85 percent of the SSBs ($20,400 ÷ $24,000), which is the maximum taxable percentage. If SSBs start at age 70, PI in those years is $46,120 ((½ × $42,240) + $25,000), which is beyond the $34,000 threshold. Taxable SSBs are $14,802, which is the lesser of $14,802 ((.85 × ($46,120 – $34,000)) + $4,500) or $35,904 (.85 × $42,240). This $14,802 is 35 percent of the SSBs ($14,802 ÷ $42,240).

- The individual’s taxable income is $51,790, which takes into account the 401(k) distribution, the taxable SSBs, and the deductions the individual is allowed. In 2015 for a single individual, the 15 percent tax bracket ends and the 25 percent tax bracket begins at $37,450 of taxable income, so $14,340 ($51,790 – $37,450) of the $20,400 of taxable SSBs fall in the 25 percent tax bracket and $6,060 ($20,400 – $14,340) fall in the 15 percent tax bracket.

- The 401(k), therefore, has a $1,082,130 balance immediately before distributions begin at age 62. As in the lower- and middle-income cases, the 401(k) has a 3.96 percent pre-tax return.

- If SSBs start at age 62, PI is $80,240 ((½ × $24,000) + $68,240), which is beyond the $34,000 threshold where the 85 percent phase-in of the SSBs’ taxability begins. Taxable SSBs are $20,400, which is the lesser of $43,804 ((.85 × ($80,240 – $34,000)) + $4,500) or $20,400 (.85 × $24,000). This $20,400 is 85 percent of the SSBs ($20,400 ÷ $24,000). If SSBs start at age 70, PI in those years is $71,120 ((½ × $42,240) + $50,000), which is beyond the $34,000 threshold. Taxable SSBs are $35,904, which is the lesser of $36,052 ((.85 × ($71,120 – $34,000)) + $4,500) or $35,904 (.85 × $42,240). This $35,904 is 85 percent of the SSBs ($35,904 ÷ $42,240).

- Note that MAGI does not take into account any itemized deductions, so planning strategies that involve itemized deductions will not affect MAGI.

- This strategy is similar to bunching itemized deductions, where the taxpayer incurs larger-than-normal itemized deductions in one year and takes the standard deduction in an adjoining year, such as by accelerating charitable contributions from the adjoining year. This strategy is especially beneficial when total itemized deductions only slightly exceed the standard deduction.

References

Garland, Susan B. 2013. “Tap an IRA Early, Delay Social Security.” Kiplinger’s Retirement Report 20 (4): 13–14.

Meyer, William, and William Reichenstein. 2013. “The Tax Torpedo: Coordinating Social Security with a Withdrawal Strategy to Minimize Taxes.” Retirement Management Journal 3 (1): 25–32.

SSA (Social Security Administration). 2015. Effect of Early or Delayed Retirement on Retirement Benefits. www.socialsecurity.gov/OACT/ProgData/ar_drc.html.

VanZante, Neal R., and Ralph B. Fritzsch. 2011. “Don’t Let Social Security Torpedo the Roth IRA Conversion Decision.” The CPA Journal 81 (4): 56–57.

Citation

Geisler, Greg, and David Hulse. 2016. “The Taxation of Social Security Benefits and Planning Implications.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (5): 52–63.