Journal of Financial Planning: November 2015

Sarah D. Asebedo, CFP®, is an assistant professor of practice in financial planning at Virginia Tech and is a doctoral candidate at Kansas State University. With 11 years of practitioner experience, Asebedo’s goal is to connect research and practice with a focus on psychological attributes and household financial behaviors.

Martin C. Seay, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor at Kansas State University. His work has been published in the Journal of Financial Planning, Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, and Journal of Consumer Affairs. He is the vice president of communications for the Academy of Financial Services and a co-host for FPA’s Theory in Practice Knowledge Circle.

Executive Summary

- This paper introduces positive psychology, illustrates how it overlaps with financial planning, and provides specific scientifically based tools and resources that financial planners can use to integrate positive psychology into their practice.

- Financial planning has naturally evolved from helping clients function financially to helping clients improve their well-being and quality of life, as evidenced in life planning, financial coaching, and financial counseling. Positive psychology has had a similar evolution over the past decade to explore how people can optimize their well-being to thrive, prosper, and flourish in life.

- Financial planning and positive psychology align through the notion of positive financial planning.

- Two client case studies illustrate that positive psychology can be integrated within financial planning in three basic ways: (1) as a perspective and orientation to financial planning; (2) as a source of scientifically based information to bring to financial planning conversations; and (3) as a positive intervention to help clients move through financial and life changes to maximize their well-being.

The common definition of flourish—to thrive, prosper, be in a period of the highest productivity or influence—reflects a basic human ambition: to live a full and prosperous life.

Given the vital role money plays in life, financial planning has naturally evolved from helping clients function financially to helping clients effectively align their money with their life’s aspirations. This shift from functioning to flourishing is evident through the emergence of life planning, financial coaching, and financial counseling.

Psychology has experienced a similar evolution of thought within the past decade as positive psychology has emerged to explore what makes life worth living. Positive psychology is on the cutting edge of research and practice on the topic of human flourishing and can provide valuable tools and resources for financial planners to help clients thrive and prosper.

This paper introduces positive psychology, illustrates how it overlaps with financial planning, and provides specific tools and resources financial planners can use to integrate positive psychology into their practice.

Introduction to Positive Psychology

Psychology can be broadly defined as the study of the mind and behavior (Anderson 2015). Peterson and Park (2003) indicated that research and practice within psychology has historically emphasized the treatment of mental illness, with less scientific effort focused on developing human strengths. Positive psychology emerged in 1998 as a field focused on correcting this imbalance (Peterson and Park 2003).

Positive psychology seeks to establish scientific evidence focused on optimizing well-being so that people can move beyond functioning to thrive, prosper, and flourish in life (Peterson and Park 2003; Seligman 2012). According to the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania (www.positivepsychology.org), positive psychology is “the scientific study of the strengths that enable individuals and communities to thrive. The field is founded on the belief that people want to lead meaningful and fulfilling lives, to cultivate what is best within themselves, and to enhance their experiences of love, work, and play.”

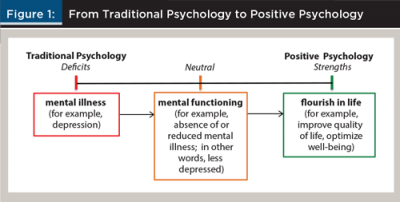

As depicted by Figure 1, positive psychology serves as a complement to traditional psychology with a focus on building strengths. This continuum can easily be applied to understanding the evolution within financial planning.

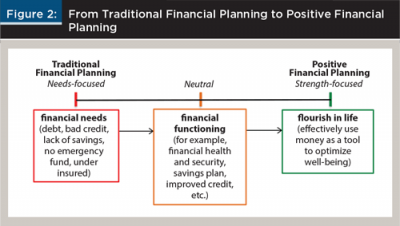

As illustrated in Figure 2, traditional financial planning has primarily focused on meeting financial needs so that clients can function in life and meet their future goals (for example, debt pay down, adequate insurance, sufficient savings for goals, etc.). Financial stability and security are typically seen as signs of financial health and indicate success in financial planning—a growing balance sheet, steady income, adequate financial ratios, a solid credit score, consistent savings, etc. It is at this neutral point that the traditional financial planning process indicates monitoring is needed to ensure financial health continues.

Positive financial planning moves beyond financial functioning and health to ensure a person’s money is maximized as a tool to optimize well-being, such that a flourishing life is possible. Positive financial planning (from the view of positive psychology) is focused on how money is related to topics such as purpose in life, meaning, achievement, supportive relationships, happiness, joy, gratitude, use of talents/strengths, and optimism, for example.

Positive psychology has gained prominence, both directly and in spirit, within the financial planning, financial coaching, and financial counseling fields over the last decade. This is often evidenced through the concept of life planning. For example, Hogan (2012) suggested life planning is a growth model with a goal to move “the client’s well-being from functional to optimal” (p. 55), clearly overlapping with the goal of positive psychology. This overlap has previously been observed. Weber (2012) proposed that basic positive psychology skills may become essential for financial planners to acquire given the prevalence of behavioral finance and life planning. Thus, financial planners who aim to extend their services beyond traditional financial planning can benefit from the wealth of scientifically based tools and resources from positive psychology.

From Psychology to Planning: Tools and Resources

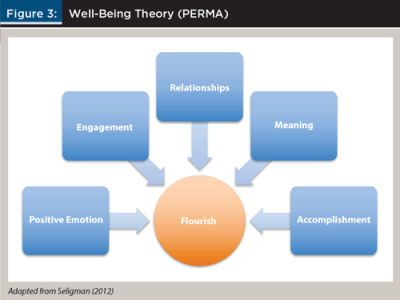

Buie and Yeske (2011) noted that scientifically grounded and evidence-based approaches are needed to expand the body of knowledge used in financial planning. In this spirit, positive psychology provides a variety of scientifically tested tools and resources that can be applied to foster client well-being. Well-being is defined and assessed through the lens of well-being theory. Well-being theory states that an individual flourishes in life when they experience the following five key elements (see Figure 3): Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment—abbreviated as PERMA (Seligman 2012).

Positive emotions reflect an individual’s subjective emotional evaluation of the past (for example, life satisfaction), present (for example, pleasure, happiness, comfort, and joy), and future (for example, optimism).

Engagement, also referred to as flow (Csikszentmihalyi 1997), is a psychological state of complete immersion and absorption into a particular task or activity that uses a person’s strengths and talents and results in the loss of self-consciousness and sense of time.

Relationships encompass the experience of healthy, supportive, and fulfilling relationships in one’s life.

Meaning refers to feelings of purpose in life and contributing or belonging to something greater than oneself.

The pursuit of mastery, success, winning, and achievement all encompass the notion of accomplishment, the fifth and final element of well-being. Through supporting and developing these five characteristics, well-being theory suggests that an individual will live a fuller and happier life.

Viewing Client Well-Being through PERMA

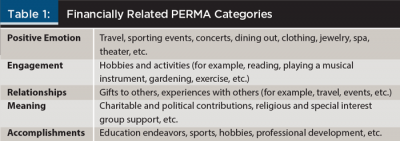

With an understanding of the PERMA elements, financial planners will be better equipped to help clients align their financial resources and behavior in ways to increase well-being. This can materialize in two basic ways. First, as part of the goal-setting process, financial planners can explore how clients are currently experiencing the PERMA elements and how they wish to experience these elements in the future. Second, when facilitating goal achievement through cash flow planning, financial planners can use a PERMA framework to ensure their recommendations do not deprive clients of the products, services, and activities that promote happiness and well-being. For example, assuming fixed expenses represent basic needs, a cash flow statement could organize discretionary expenses according to the PERMA elements to determine how spending is supporting and optimizing well-being.

Table 1 illustrates common goals and related spending categories organized according to the PERMA elements, which may naturally overlap (for example, a hobby may provide a sense of engagement, positive emotion, and accomplishment).

Measuring Client Well-Being

An understanding of PERMA is only useful if it can be applied easily in practice. A variety of resources are available for measuring and evaluating well-being. The University of Pennsylvania’s Authentic Happiness website provides a series of user-friendly questionnaires to evaluate an individual’s well-being based upon psychometrically validated scales (see www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu/testcenter).

As an example, meaning in life, representative of the “M” element of PERMA, is measured based upon the following 10 questions with responses for each question ranging from 1 (absolutely untrue) to 7 (absolutely true) (see www.positivepsychology.org/resources/questionnaires-researchers):

- I understand my life’s meaning.

- I am looking for something that makes my life feel meaningful.

- I am always looking to find my life’s purpose.

- My life has a clear sense of purpose.

- I have a good sense of what makes my life meaningful.

- I have discovered a satisfying life purpose.

- I am always searching for something that makes my life feel significant.

- I am seeking a purpose or mission for my life.

- My life has no clear purpose.

- I am searching for meaning in my life.

With question 9 responses reversed (1 becomes a 7), higher average scores would indicate a greater sense of purpose and meaning in life. In practice, if a client produces a lower score, then a financial planner could help the client determine how to reallocate their financial resources or reshape their goals to foster more meaning in life (for example, charitable giving strategy or more time away from work to volunteer or be with family, etc.). A client’s evaluation of their scores might be enlightening to them personally by highlighting which positive psychological attributes are low or missing. This will provide internal reflection and awareness, which is often the first step before change occurs.

Equipped with these well-being measurements, financial planners can gain an understanding of the positive psychological attributes currently present in clients’ lives. Although these scales are not intended to be diagnostic, they can be used to gain insight into the client’s way of thinking. Thus, these tools will create valuable relationship-development conversations, as well as provide information that can be used to frame the goal-setting and cash flow allocation process to promote well-being.

Promoting Client Well-Being with Positive Psychological Exercises

The following three exercises are used in positive psychology practice and have been shown to increase happiness and reduce depressive symptoms over long periods of time (Seligman, Steen, Park, and Peterson, 2005). More details regarding these exercises can be found in the book, Flourish (Seligman 2012).

What-went-well exercise. This exercise promotes a variety of positive psychological attributes such as gratitude, optimism, accomplishment, and happiness. The purpose of this exercise is to change your client’s focus from problems to successes so that a negative outlook no longer dominates thought and creates anxiety. Bad events should not be ignored; however, dwelling on them can detract from forward progress and life enjoyment.

The instructions for this exercise are simple; at the end of each day for one week, have your client write down three things that went well and why they went well. It is important to encourage your client to spend sufficient time thinking about why these things went well as the explanatory style (see developing optimism below) deployed for both good and bad events can significantly impact future action.

This exercise could be particularly useful in financial planning when clients experience major financial and life events, such as retirement. The transition to retirement can be an emotional minefield and it may be beneficial for a client to document three good things a day about their new retirement life. This exercise may also be beneficial for clients struggling to gain control over their finances, trying to move past negative financial events, or attempting financial behavior change. These financial events or decisions do not have to be significant (“I stayed within my budget today because I felt in control and realized I didn’t need to purchase a new watch”), but can also be associated with a major event (“Today I received a promotion at work because I am talented and work hard”). Overall, this exercise will encourage clients to focus on what went well financially in their lives and why, providing for a much happier and open-minded client experience.

Signature strengths exercise. The purpose of this exercise is for clients to discover their signature character strengths by taking the Values in Action (VIA) Signature Strengths survey by the VIA Institute on Character (www.viacharacter.org). This survey is designed to help people uncover and apply their unique character strengths in order to increase their overall well-being. It encompasses 24 character strengths organized within six broad virtue categories: wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. The VIA Signature Strengths survey is set apart from the widely known StrengthsFinder assessment by Gallup, as it provides for a robust, scientifically validated, and broadly applicable tool that can be used within many different contexts (Neimiec 2013). The primary idea behind this exercise is to understand key strengths and purposefully increase the creative use of them.

Given the results of this test, have clients allocate a specific block of time to use one of their top five strengths in a new way. For example, if one of their top signature strengths is kindness, they could find a good deed to do for a family member, friend, or stranger in the next week. Understanding clients’ signature strengths can help financial planners develop a plan to allocate sufficient financial resources toward using those strengths. This exercise may help clients entering retirement to envision a plan for how they can continue using their strengths when traditional work is no longer an outlet. Moreover, a client in their working years may realize they are not using their strengths in their current job and may wish to explore a career change.

The gratitude visit. Gratitude is a positive emotion within the PERMA framework that promotes both personal and social benefits. Gratitude is typically derived from recognizing the impactful contributions others make to our lives. The gratitude visit provides personal and social benefits through expressing gratitude to another person in a purposeful and thoughtful way (Seligman 2012).

The first step is to have your client reflect and imagine a person who positively contributed to their life who they could meet with in person. Next, have the client sit down and write a thoughtful, clear, brief (about 300-word) letter to that person. This letter should clearly describe the person’s contribution, how it was impactful at the time, and what it means today. With the letter in hand, have the client reach out to that person to arrange a visit, but keep the letter a surprise. During the meeting, the client can read the letter to the person and spend time talking about the event and their relationship.

Financial planners are in a unique position to help clients identify gratitude visit opportunities as the client’s story unfolds over time, particularly as it relates to the financial realm. For example, the gratitude visit could be for someone who helped them get their first job or a promotion, a parent or relative who provided financial support, a career mentor, a spouse who made a financial sacrifice for the family, or a friend who helped during tough times.

It is not uncommon for financial planners to work with multiple generations at one time. Parents’ perceived gratitude from adult children for financial support has been shown to have a positive effect on the parents’ psychological well-being (Byers, Levy, Allore, Bruce, and Kasl 2008). Therefore, this exercise could be a powerful tool in cultivating positive money relationships within families when working with multiple generations.

Developing Optimism

Optimism, an element of the positive emotion construct of PERMA, has received significant attention within positive psychology. Optimism has been shown to be a powerful emotion that is beneficial in many ways, not the least of which is promoting better physical health. Optimism may be related to better physical health for three primary reasons (Seligman 2012): (1) optimists believe actions matter and follow through on advice; (2) optimists tend to have more social support; and (3) optimists may have biological mechanisms promoting better health, such as a more aggressive immune system. Thus, cultivating optimism is recognized as a worthy pursuit and can be accomplished over time (Seligman 2011).

Financial planners may struggle to understand the gap between advice and action. Although topic-specific research is needed, the general body of optimism research suggests a client’s psychological perspective may play a role in this observed disconnect.

Because optimists are more likely to follow through on advice, financial planners might benefit from focusing on this emotion when providing long-term planning recommendations. First, a financial planner can have a client complete an optimism measurement questionnaire to understand the status of the client’s current optimistic disposition. A client may benefit from optimism-building exercises if the client demonstrates a lower score or produces a higher score yet says yes to any of the following questions (Seligman 2011, p. 208):

- Do I get discouraged easily?

- Do I get depressed more than I want to?

- Do I fail more than I think I should?

Once the client’s current optimism level is understood, the following three tools and resources can be used to promote and cultivate an optimistic perspective (Seligman 2011).

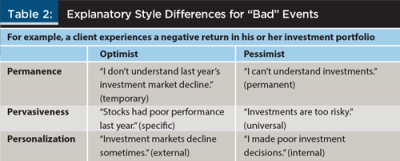

Understand your clients’ explanatory style. It is important to understand a client’s explanatory style, as optimism and pessimism are primarily characterized by how people habitually explain good and bad events. Given an event, an individual’s explanatory style is the way in which they attribute causes to the event and is defined by three dimensions: permanence, pervasiveness, and personalization.

The Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ) is commonly used to measure an individual’s explanatory style (Peterson and Steen 2002). A user-friendly scale is also available through the University of Pennsylvania’s Authentic Happiness website (www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu).

Permanence is about time and the attribution of temporary or permanent causes for an event.

Pervasiveness is about space and the association of specific or universal causes to an event.

Personalization is about the attribution of the cause to oneself (internal) or other environmental or circumstantial factors (external). For example, suppose a client experiences a negative return in their investment portfolio. Table 2 represents the explanatory style differences between optimists and pessimists for this bad event.

The responses to good events are the exact opposite from bad events, as an optimist would interpret a good event to be based on permanent, universal, and internal causes; a pessimist would attribute the good event to temporary, specific, and external reasons. Within the financial planning context, pessimistic clients may be more resistant to advice, as negative financial events are likely to be interpreted as a personal deficiency, to resonate longer, and to have broader implications than what is necessary.

The ABCs. The Activating events, Beliefs, and Consequences (ABC) schema is well established within psychology. The basic premise behind the ABCs is that a person’s positive or negative thoughts affect their interpretation of an event, thereby forming beliefs that impact their emotional response and behavior (Ellis 1991). Therefore, a more constructive outcome can be achieved by changing the way people think.

To discover a person’s ABC sequence, Seligman (2011) recommends that individuals record five ABC patterns over the course of a one-week period to gain insight into their habitual way of thinking. The interpretive beliefs formed as a result of the event represent a person’s explanatory style (permanence, pervasiveness, and personalization). The link between beliefs and consequences are important as “pessimistic explanations set off passivity and dejection, whereas optimistic explanations energize” (Seligman 2011, p. 216).

In a financial planning context, the ABCs can provide a framework to help people discover specific financial events (overspending) that give rise to interpretive beliefs (“I am poor at managing money”) resulting in emotional consequences (despair). By recording actual events, beliefs, and consequences as they relate to financial behavior, a financial planner can help a client uncover the internal messages that may be thwarting (pessimism) or helping (optimism) their efforts. Using the previous overspending example, a pessimistic ABC pattern may look something like this:

Activating event: “I stopped by the mall on my way home from work and completely blew my budget this month.”

Belief: “I just can’t manage my money. I’m weak and will never be able to save enough for my retirement.”

Consequence: “I feel like giving up.”

Dispute your beliefs (disputation) and energize. Adding D and E to the ABC model, Ellis (1991) suggests Disputing negative thought patterns to arrive at an effective new philosophy, which results in an Energizing solution (Seligman 2011).

Beliefs are often a version of reality and disputation involves changing oneself to develop a more realistic and objective view of a situation. To dispute beliefs it is necessary to focus on four areas (Seligman 2011): (1) provide evidence that the belief is factually incorrect; (2) suggest alternatives as to why the event occurred; (3) consider implications if the belief is in fact true; and (4) consider if the belief is useful or destructive.

Following the overspending ABC pattern from above, “D” and “E” could take the following form:

Disputation: “Yes, today I blew my budget, but it’s not accurate that I can’t manage my money. That is a destructive belief and I need to let it go. For the last two months I’ve followed through with my saving plan and have not overspent. I was stressed at work today and the purchases helped me feel better at the time.”

Energize: “I feel motivated to try new methods to stick to my budget. Perhaps I should explore why I felt so stressed at work and try to address that. I will have to spend less next month so I can pay off my credit card bill from this month due to my shopping trip.”

Optimism is a powerful, positive psychological attribute; it helps people bounce back from adverse situations, thereby giving way to energizing thoughts and actions. Financial planners can have a significant impact on the disputation process because they naturally bring an objective vantage point to a client’s situation. Given the emotions and behavioral aspects intertwined with money that often inhibit action, it is beneficial for financial planners to understand how they can promote an optimistic perspective for their clients.

Positive Financial Planning In Action: Two Case Studies

Positive psychology can be integrated into financial planning in three fundamental ways: (1) as a perspective and orientation to financial planning; (2) as a source of scientifically based information to bring to financial planning conversations; and (3) as a positive intervention to help clients move through financial and life changes to maximize their well-being. This is similar to an integrative framework that has been proposed for positive psychology and life coaching (Joseph 2015). Given this backdrop, consider the following two case studies to explore how positive financial planning can be implemented in practice.

Case Study 1: Jason

Jason, age 65 and single, retired four months ago from his corporate executive position. He feels financially secure and is not concerned about money. He has two children he hasn’t seen much due to his busy work schedule over the past several years. Jason recently met with his financial planner, Megan, and was visibly distressed. Megan was surprised and curious, as Jason is in fantastic financial shape with a comfortable retirement income. Megan, concerned, decided to explore further.

Megan: “Jason, something seems different about you and I’m sensing stress. During our last meeting you were so excited to retire and had many plans. Can you tell me more about what has changed over the last four months?”

Jason: “I’m not happy and I can’t put my finger on it. I’ve traveled, golfed more, and done volunteer work and am starting to feel bored and empty.”

Megan: “I see, so your new retirement life isn’t exactly what you thought it would be?”

Jason: “That’s right. I need to make some changes but am a bit lost as to what to do. I didn’t expect to feel this way.”

Megan: “The retirement transition can be hard and you are not alone in your experience. I would like you to try a couple of things before our next meeting. There are some tools and resources from positive psychology that can help us understand and explore what makes life worth living. Does that sound like something you would be interested in?”

Jason: “Yes, let’s give it a shot.”

Megan gave Jason the following homework to complete over the next month:

- Complete the VIA Signature Strengths and PERMA flourishing questionnaires.

- Complete the signature strengths and what-went-well exercises.

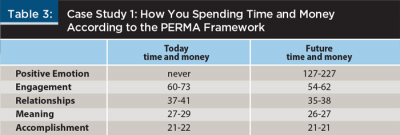

- Observe and write down how you are spending both your time and money according to the PERMA framework today and what it could look like in the future if you were to experience each of these elements to the fullest.

After completing the above exercises one month later, Megan met with Jason and helped him interpret and process the results. Jason discovered through the questionnaires that although he was happy at times, his overall well-being was less than optimal, because his PERMA elements were over-weighted toward positive emotions. When examining his cash flow and allocation of time (see Table 3), Jason observed that the majority of his time and money were spent on things that facilitated positive emotions, with engagement, relationships, and accomplishment substantially neglected. Although time and money were being spent on meaning, Jason noticed that he was psychologically lacking in that area.

The forward-looking component of the PERMA time and money worksheet helped Jason envision changes he could make in his life to build out the PERMA areas further (see Table 3). The signature strength exercise was useful to Jason, as he had begun to incorporate two of his top five strengths into his life as a result (leadership and love of learning, according to Table 3), which enhanced his sense of meaning, accomplishment, and engagement.

The what-went-well exercise helped him to feel generally happier and reaffirmed that he highly valued interactions with his children and that it would be mutually beneficial to foster those relationships. By the end of the meeting, Megan and Jason had developed a plan to realign his budget to support his newly found goals and dreams. This did mean less golfing, but a fuller and more meaningful life that he could share with his children and the community was now in reach. Jason left that meeting smiling and with a bounce in his step that wasn’t there the last time.

As illustrated by Jason’s story, the exercises and tools from positive psychology provided Megan with a sound, coherent, and integrated framework from which to explore Jason’s situation. Throughout the process, Megan gained valuable insight that enabled her to develop an action plan to align Jason’s money with his life. While this situation is an example of a positive intervention, these tools and resources can also be used proactively when onboarding new clients and prior to major life transitions. Jason would have benefited greatly from exploring these topics prior to his retirement or even earlier during his working years.

Case Study 2: Tom and Adriana

With three busy kids and two full-time jobs, Tom and Adriana barely have time to discuss their personal finances. When they do talk about money, they typically end up in an argument that ends with no resolution or action. Tom and Adriana are stuck. In desperate need of help, they begin working with a financial planner named Julian.

Julian proactively incorporates positive psychology into his practice and has new clients complete positive psychology questionnaires as part of his onboarding process. Julian’s standard forms for gathering Tom and Adriana’s financial data and goals did not indicate anything unusual. They had typical goals for a young couple in their early 40s, including education funding for their children and a planned retirement in their mid-60s. Based on the positive psychology questionnaires, however, Julian noticed that Tom scored low in optimism, happiness, and work-life satisfaction. Adriana on the other hand, had high scores in all areas except for happiness. Their first meeting with Julian went like this:

Julian: “Tom and Adriana, thank you for completing all of the initial questionnaires and data-gathering forms. I know it is a lot of work but it helps me to better understand your situation. Before we dig in, I would love to hear in your own words what each of you think are the top financial priorities in your lives at this time.”

Tom: “Well, we aren’t making any progress whatsoever with our finances. We have a huge mortgage and I don’t think we’ve saved enough for the kids’ education. Every time we talk about these things we end up arguing. We don’t work together well when it comes to money.”

Julian: “Alright, it sounds like debt pay down, education funding, and improving your relationship with Adriana around money are at the top of your list. Is that right?”

Tom: “Yes.”

Julian: “Adriana, what do you think?”

Adriana: “Yes, the mortgage and education funding are important, and we do argue mostly about those items. We didn’t always fight like this. The arguments became much more frequent after my parents started giving us money two years ago.”

Julian: “Okay, so I’m hearing that the mortgage and education funding goals are really important to you both. Also, it sounds like there was a time when there were less money arguments between the two of you. Tom, can you think of a time when you and Adriana worked well together around the household finances?”

Tom: “Well, a couple of years ago we had some great conversations around education funding and started saving in 529 plans for the kids. We also agreed to cut back on our spending so that we could save the maximum in our retirement plans. We’ve stuck to our saving and spending goals ever since.”

Julian: “That’s great! When I reviewed your financial documents, I was impressed by how much you have accomplished already for retirement and education. Tom, earlier you said that you and Adriana don’t work well together when it comes to money and that you haven’t made any progress with your finances. Do you think these statements may not be entirely true?”

Tom: “Well, actually you’re right—they aren’t completely true. There are certain areas in which we do work well together, like saving for retirement and starting our education savings. After Adriana’s parents started giving us money every year, we purchased a larger house with a larger mortgage and decided to fund all of our children’s education. Prior to this we were only going to fund their education at 50 percent. I’m so stressed at work I don’t know how much longer I can keep going; however, with the larger expenses and savings needs, I feel like I have to.”

Julian: “Well, we can certainly crunch some numbers to see how the increased expenses and savings fit into the long-term plan. I also want to better understand your work situation. I noticed you scored rather low on the work-life satisfaction questionnaire so I’m not surprised to hear your comment about work-related stress. Adriana, it seems like things changed after your parents started giving you and Tom gifts. What are your thoughts on that?”

Adriana: “My parents really want to help us and the gifts make a big difference, but I do think we have increased our lifestyle because of them. Tom and I have fought a lot more lately and I think it is because of the increased pressure he feels to support our expenses and goals, which the gifts actually cover. Also, I’m very thankful for the gifts but I’m not sure how to express my appreciation to my parents.”

Julian: “Thank you both for sharing your views—this has been a very helpful first meeting. I have some ideas that I think will help you continue with your progress and relieve some of the money arguments you are having. Are you ready to try some new ideas?”

Tom and Adriana: “Yes!”

Julian proceeded to review the questionnaire results with Tom and Adriana to deepen the conversation. Julian explained the gratitude visit to Adriana and suggested she try it with her parents. Adriana found the gratitude visit to be emotionally rewarding. The visit also opened a new line of communication with her parents as she discovered they had begun to contribute to their own education accounts for the grandkids.

Julian worked with Tom to explore his key strengths with the VIA Signature Strengths test. Tom was able to find new ways to use his key strengths at work and found his stress level had greatly diminished as a result.

During the first meeting, Julian skillfully disputed Tom’s belief that he and Adriana were not making progress on goals and could not work together around money. Julian also focused adverse situations on the specific problems, keeping Tom from personalizing and generalizing the negative events beyond what was necessary. By integrating positive psychology into his practice, Julian was able to find practical solutions that improved his clients’ overall sense of financial and emotional well-being.

Conclusion

Financial planning and positive psychology align through the notion of positive financial planning, as seen in life planning, financial coaching, and financial counseling. With money and well-being united through positive psychology and financial planning, clients can flourish.

Financial planners are in a unique position to help clients uncover and attain their best possible life and can learn valuable information from positive psychology on the topic of human flourishing. While positive psychology provides a framework for understanding client well-being, it is important for a financial planner to understand the bounds of their expertise. Thus, a financial planner may wish to partner with a mental health professional depending upon the client situation.

Additional tools and resources in positive psychology can also be found in the book, Positive Psychology in Practice: Promoting Human Flourishing in Work, Health, Education, and Everyday Life, 2nd Edition. Continued research and practitioner experiences that provide evidence for the effectiveness of positive psychology within financial planning are needed as positive financial planning continues to gain prevalence.

References

Anderson. 2015. “This Is Psychology: What Is Psychology?” Video and transcript from the American Psychological Association. Retrieved from www.apa.org/research/action/this-is-psychology/introduction.aspx.

Buie, Elissa, and Dave Yeske. 2011. “Evidence-Based Financial Planning: To Learn ... Like a CFP.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (11): 38–43.

Byers, Amy L., Becca R. Levy, Heather G. Allore, Martha L. Bruce, and Stanislav V. Kasl. 2008. “When Parents Matter to their Adult Children: Filial Reliance Associated with Parents’ Depressive Symptoms.” The Journals of Gerontology 63B (1): 33–40.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1997. Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Ellis, Albert. 1991. “The Revised ABCs of Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET).” Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 9 (3): 139–172.

Hogan, Paula H. 2012. “Financial Planning: A Look from the Outside In.” Journal of Financial Planning 25 (6): 54–60.

Joseph, Stephen, ed. 2015. Positive Psychology in Practice: Promoting Human Flourishing in Work, Health, Education, and Everyday Life, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Neimiec, Ryan, M. 2013. “VIA Survey or StrengthsFinder?” Psychology Today blog, posted December 17.

Peterson, C., and Tracy A. Steen. 2002. “Optimistic Explanatory Style.” In. C.R. Snyder, SJ. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Peterson, Christopher, and Nansook Park. 2003. “Positive Psychology as the Evenhanded Positive Psychologist Views It.” Psychological Inquiry 14 (2): 143–147.

Seligman, Martin E. 2011. Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life. New York, NY: Random House Digital, Inc.

Seligman, Martin E. 2012. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Seligman, Martin, E., Tracy A. Steen, Nansook Park, Christopher Peterson. 2005. “Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions.” American Psychologist 60 (5): 410–421.

Weber, Keith. 2012. “Planning Parallels with Positive Psychology.” Bank Investment Consultant 20 (1): 21.

Citation

Asebedo, Sarah, and Martin Seay. 2015. “From Functioning to Flourishing: Applying Positive Psychology to Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (11): 50–58.