Journal of Financial Planning: November 2019

Executive Summary

- 529 plans offer tax advantages, however they come with more complexity in account set-up, fewer investment options, potentially higher fees, and less flexibility than a taxable account. This research looks at whether the tax advantages provided by 529 plans are too good to pass up.

- One primary determinant of the magnitude of the potential tax advantage is the home state of the client. In states with higher income tax rates and larger 529 plan incentives (deductions or credits), 529 plans provide a substantial tax benefit versus taxable accounts. In states with no income tax, 529 plans provide a smaller tax benefit.

- The relative tax advantage of 529 plans also depends on the length of time the client has until college, whether the contributions will be gradual or in a lump sum, and the assumed rate of return on the investments.

- This analysis calculates a “tax alpha” on a state-by-state basis as a reference guide for planners who work across many states to help make an initial assessment of whether the 529 plan offers relatively large or small tax advantages versus a taxable account. This can allow a planner to quantify the relative tax benefit of a 529 plan versus a taxable account for college savings, depending on the home state of the client.

Luke Delorme, CFP®, is the director of financial planning at American Investment Services, a fee-only advisory firm located in Western Massachusetts with clients across the U.S. and globally. He is a former research fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research where his research focused on retirement studies, investment economics, and personal finance. He also previously worked at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Analysis Group, and State Street Global Markets.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

A 529 plan is the primary investment vehicle available today to help ease the burden of college planning. However, the marginal benefit of a 529 plan can vary depending on where a client lives. Financial planners who work with clients across many states should be able to quantify the relative tax benefit of a 529 plan versus a taxable account.

Moreover, 529 plans require more paperwork than an alternative saving vehicle, such as a taxable brokerage account. They also have fewer investment options (which may potentially be suboptimal), may come with higher fees, and offer less flexibility when it comes to spending if the funds do not end up being used for college or private education as anticipated.

The bottom line is, for a financial planner, it can be difficult to know when you should recommend a 529 plan as opposed to recommending clients simply save in a taxable brokerage account (or a Roth IRA, as is sometimes the recommendation). This analysis aims to measure the potential tax advantages of 529 plans on a state-by-state basis, based on idiosyncratic state tax laws, as a reference guide for planners. It is not an analysis of which state plan is best. Keep in mind that the rules regarding 529 plans are subject to change, so planners should confirm that the information is up to date. State data is accurate as of the time of this research in 2019, but state tax laws should be corroborated before implementing any decision.1

Previous Literature

The academic literature on 529 plans broadly spans three categories: (1) investment selection within and amongst various plans; (2) broader economic and policy implications; and (3) the overall usefulness of 529 plans as a vehicle for college saving.

Researchers have found that investors often make suboptimal decisions with regard to selecting investments within a 529 plan (DeGennaro 2004; Alexander, Luna, and Gill 2015). Investors also make suboptimal decisions about which state’s plan will best optimize taxes (Alexander and Luna 2005).

Several papers have looked at how advisers should approach asset allocation in 529 plans. For example, Chang and Krueger (2018) found that planners should especially pay attention to mutual fund charges when choosing a 529 portfolio, but not be too concerned about the portfolio equity concentration.

This paper only tangentially addresses specific plan selection and does not address investment selection, but those are areas where financial planners can add value for clients. Asset allocation within 529 plans, or in a taxable account with the objective of providing college funds, is a complex topic that should take into account investor circumstances and the investment portfolio more holistically. DeGennaro (2004) specifically advised planners to consider asset location—the strategy of concentrating more tax-efficient assets in taxable accounts.

The research on the policy implications of 529 plans has generally explored who is most likely to benefit from 529 plans, and who is taking advantage of these plans. The majority of plan participants come from higher-income families. As of 2013, 16 percent of families in the top 5 percent of income held 529 plans, compared with 2.5 percent of the overall population (Hannon, Moore, Schmeiser, and Stefanescu 2016).

Hannon et al. (2016) also found that the average balance was significantly higher among higher-income households. For households not in the top 5 percent of income, 529 plans may lose popularity, because they can reduce the opportunity for financial aid. These households may be dedicating additional funds toward saving in tax-advantaged retirement plans—401(k)s and IRAs, for example—that do not reduce the potential for financial aid.

Researchers have argued that 529 plans help higher-income households much more than lower-income households (Dynarski 2004), sometimes suggesting that 529 plans are not “progressive” enough (Clancy, Sherraden, Huelsman, Newville, and Boshara 2009; and Aldeman 2011).

The academic literature on the overall usefulness of 529 plans, to which this paper aims to add, is significant. Most argue that 529 plans are the optimal avenue to pay for a descendant’s college expenses (e.g., Gardner and Daff 2017). However, early research on 529 plans suggested that adherence to predetermined asset allocations may result in less optimal results than a more aggressive strategy within a taxable account (Spitzer and Singh 2001). Alternatively, investors could choose to adopt an aggressive asset allocation within a 529 plan. Spitzer and Singh (2001) did not discuss in depth the possibility that investors may be uncomfortable with an equity-heavy allocation as their children approach college age.

A 2010 Morningstar research paper offered an analysis of 529 plan tax benefits by state (Alpert, Charlson, Liu, Lutton, and West 2010). That research found that for most college savers who were saving less than $25,000, the tax benefits of their home states’ 529 plan often outweighed the adverse attributes, such as mediocre investment options or higher fees.

Toner (2019) calculated the potential annual 529 plan tax savings by state for a couple filing jointly with $100,000 taxable income contributing $100 a month to each of two children’s 529 plans. Results showed that the best tax savings can be expected in Indiana, followed by Vermont, Iowa, and Oregon. Toner (2019) also provided a tool that estimates annual state tax savings based on state of residence, marital status, taxable income, and monthly contribution.2

Pressman and Scott (2017) pointed out that 529 plans are complicated, rules vary by state, and fund management fees tend to be high. “Thus, 529 plans are not the panacea to college affordability” (page 375). This study adds to the existing literature by analyzing under what circumstances a financial planner should consider recommending a 529 plan for his or her clients. By looking at a client’s current tax circumstances, when they want to start saving, how long they have until college, and their home state, a financial planner can quantify how advantageous a 529 plan might be, compared to non-tax advantaged investment vehicles.

What Are the Tax Advantages?

Money invested in 529 plans is invested on an after-tax basis. The investments in 529 plans grow tax-free. When the funds are used to pay for qualified college expenses (tuition, books, some room and board, computers), investment earnings are not taxed.3 This incentive is largest when the invested funds have a long time to grow, accumulating significant investment gains. The primary tax advantage of 529 plans is the avoidance of federal and state capital gains taxes on qualified withdrawals for tuition. This incentive can vary depending on the state tax rate.

Another major tax advantage of 529 plans can be the deductibility of contributions, or even more favorable tax credits, that are available only in certain states. The total deductible amount varies by state, but often covers up to $10,000 for a married couple. Four states (Indiana, Utah, Vermont, and Minnesota) offer a more generous state income tax credit. However, 16 states have no income tax deduction or credit for 529 plan contributions.

The nine states that do not have an income tax are: Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming.4 Seven states impose state income taxes but do not offer a deduction for contributions to a 529 plan: California, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, New Jersey, and North Carolina.

Taxpayers generally contribute no more than $15,000 per year to a 529 plan in order to avoid triggering gift taxes.5 However, plans can be “superfunded” with contributions spread out over five years for gift tax purposes. This would allow a married couple to contribute up to $150,000 per beneficiary in a single year without creating a taxable event ($15,000 x five years x two donors). These large potential contributions to tax-advantaged 529 plans make it important to assess the magnitude of the potential tax benefits for clients looking to help children and grandchildren pay for college.

Analysis

This analysis extended previous studies by looking at potential capital gains taxes (state and federal), state deductibility or credits, varying the accumulation period (five, 10, or 15 years), assessing different rates of return (4 percent, 6 percent, or 8 percent), and evaluating the timing of contributions (lump sum versus annual).

The measure created to quantify the tax advantage of 529 plans is called the tax alpha. This is the excess return generated by a 529 plan through tax advantages alone, as compared with a taxable account. The tax alpha includes state tax deductions or credits on contributions, state capital gains tax exemptions on investment earnings, and federal capital gains tax exemptions on investment earnings. The tax alpha, as calculated in this study, did not include tax avoidance on interest, dividends, or capital gains distributions that may have be incurred on an annual basis in taxable accounts.6

The tax alpha was calculated as the excess annual return a taxable brokerage account would need to provide in order to match the total funds available for college spending when a 529 plan was used. The gross dollar difference in account values was smaller over shorter periods because there was less opportunity for investment growth. However, the calculated tax alpha was higher over shorter periods because of the relative impact of tax deductions.

The calculated tax alpha may be best explained through an example. Assume a married couple, filing jointly with $100,000 taxable income, are living in Connecticut. They have the ability to save $3,000 per year at the beginning of each of the next 10 years for their daughter to attend college. For the sake of this analysis, they can choose between a 529 plan and a taxable brokerage account. What is the amount of excess return they would need from a taxable account to make it as valuable as the 529 plan at the end of 10 years? The tax alpha is calculated as follows:

1. State deduction. Connecticut offers residents an income tax deduction up to $10,000 per married couple. The marginal tax bracket for the couple is 5.50 percent. This means that a $3,000 contribution would generate tax savings of $165 per year ($3,000 x 0.055). It is assumed that they contribute this extra $165 per year to the 529 plan.7

2. Exclusion of capital gains. If the couple uses the 529 plan, they receive an exemption on federal and state capital gains when the money is withdrawn. In a taxable account, capital gains would be taxed at the federal rate of 15 percent and the state rate of 5.50 percent. In 10 years, at an annual growth rate of 6 percent, these capital gains total $11,915 in a taxable account that receives contributions of $3,000 per year.

3. Calculating the total difference. At the end of 10 years, the total contribution is $30,000. Additional contributions to a 529 plan would be $1,650 from the state income tax exemption ($165 x 10 annual contributions). Total investment earnings on the 529 plan are $12,570 (6 percent rate of return). Investment earnings on the comparable taxable account would have been $11,915 lower, because there was a lower total contribution. After capital gains taxes, however, gains on the taxable account are reduced to $9,472.

At the end of 10 years, the 529 plan would have $44,220 available for qualified education expenses. The taxable account would have $39,472 available after tax.

4. Calculate the tax alpha. The tax alpha is the difference in internal rate of return (IRR) on a $3,000 annual contribution for the 529 plan versus the taxable account.

In this case, the IRR on the 529 plan was 6.95 percent (better than the 6 percent actual return because of the annual state tax deduction). The IRR on the taxable account was 4.93 percent (less than the 6 percent rate of return because of state and federal capital gains taxes).

The calculated tax alpha is therefore 2.01 percent.8 In this case, the tax alpha is a hurdle for the taxable account. A financial planner advising this example client in Connecticut should almost certainly recommend 529 plans for college saving.

Assumptions. For simplicity, the federal deduction for state taxes paid was ignored. As discussed previously, any annual taxes paid on interest, dividends, or capital gains distributions in the taxable account were also ignored. Finally, state capital gains taxes were for the current state of residence only.

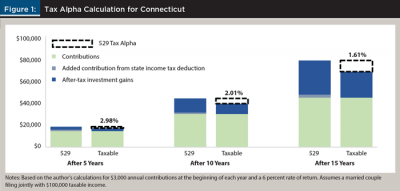

A graphical example for Connecticut is shown in Figure 1. In the example of Connecticut, the tax alpha for a five-year period would be 2.98 percent. Over longer periods, the tax alpha falls. Over the 15-year period, the tax alpha falls to 1.61 percent. These findings are discussed more generally in the results section.

Results

The tax alpha from investing in a 529 plan versus a taxable account is always positive in the analysis due to the avoidance of federal capital gains taxes. However, the calculated tax alpha ranges from less than 1 percent to more than 4 percent over a 10-year investment horizon.

A number of variables can affect the calculated tax alpha of 529 plans. The most important variable is the home state of the contributor. A table of calculated tax alpha by state is provided later in this paper. Other variables include the length of the investment horizon, the rate of return, and how money is contributed (lump sum or gradually).

Length of investment horizon. The shorter the length of time for investment, the larger the tax alpha created through 529 plans due to the relative impact of tax benefits. Although the gross dollar amount of difference is smaller, the percentage tax alpha is higher. The example of Connecticut shown in Figure 1 illustrates this difference.

In the Connecticut example, the gross difference in accumulation is $1,586 after five years. That difference increases to $4,748 after 10 years, and to $10,020 after 15 years. As the length of time increases, the gross marginal dollar benefit of the 529 plan grows, but the tax alpha shrinks.

One conclusion from this result is that the excess rate of return needed for taxable accounts to match 529 plans is not as high over longer periods. Investors who think they can do significantly better than 529 plan investment options might consider using taxable accounts. On the other hand, sacrificing potential tax alpha by avoiding 529 plans can have a big impact on total accumulation over longer periods of time if investments do not outperform as expected.

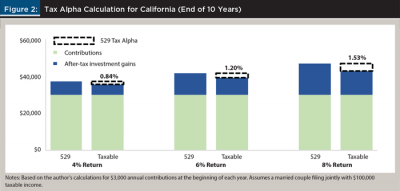

Rate of return. The higher the rate of return, the higher the tax alpha of the 529 plan. Higher returns result in a larger gross dollar difference between 529 plans and taxable accounts and also result in a higher tax alpha. Lower returns result in a lower tax alpha and a smaller gross difference.

California is shown in Figure 2, with an 8.0 percent capital gains tax rate for the example household ($100,000 taxable income, married filing jointly). California does not offer income tax deductions on contributions. In this example, the California tax alpha is calculated as 0.84 percent for a 4 percent return; 1.20 percent for a 6 percent return; and 1.53 percent for an 8 percent return. The gross difference in accumulation is $1,716 with a return of 4 percent; $2,740 with a return of 6 percent; and $3,895 with a return of 8 percent. As the return increases, the gross dollar benefit of the 529 plan grows and the total tax alpha increases.

One conclusion is that investors unwilling to take on much risk with college savings, such as those with children close to college age in fixed income-heavy allocations, are not likely to reap as much benefit from using a 529 plan.

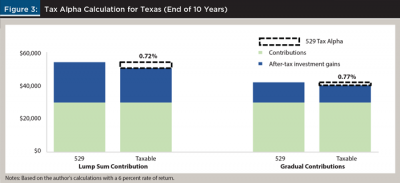

Timing of contributions. Some clients are faced with a decision of whether to fund college savings gradually or with a large one-time lump sum. This analysis compared the two strategies. In the first scenario, the client makes a $3,000 annual contribution to college savings for 10 years. In the second strategy, a one-time $30,000 contribution is made at the outset of the savings period.

The income tax deduction has the potential to be reduced in states that allow partial deductions of contributions (although some states allow carry forwards). For example, New York state offers deductions up to $10,000 per beneficiary for a married couple, so a $30,000 contribution would only allow for a $10,000 deduction.

For the purposes of an example, a state with no income tax deduction is shown to see the impact of the funding strategy. Texas is one of the states with no capital gains taxes, reducing the overall tax alpha. The tax alpha that shows up in Texas is only the result of the federal capital gains tax avoided.

The lump sum contribution results in a lower tax alpha than the gradual contribution, but a larger gross dollar difference in accumulation. The difference in accumulation is $3,559 for the lump sum contribution and $1,787 for the gradual contributions. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

State-by-State Analysis

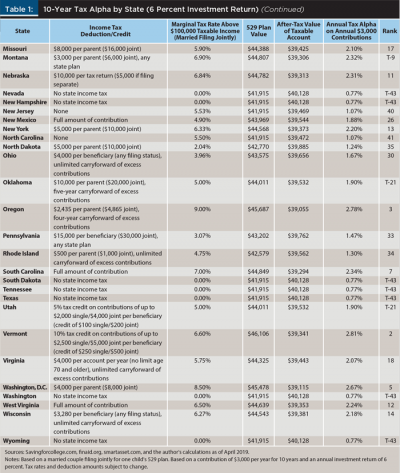

A number of factors affect the expected tax alpha of 529 plans, but the largest driver is the home state. This is due to the idiosyncratic nature of deductions and capital gains taxes across states. Table 1 estimates the 529 plan tax alpha for each state. This baseline assumes a $3,000 annual contribution by a married couple to one child over the course of 10 years. Contributions are made at the beginning of each year, and the tax alpha is estimated at the end of 10 years.

The largest tax alpha can be found in Indiana. Indiana offers a 20 percent tax credit on contributions up to $5,000. This is like a $600 boost per year in the 529 plan for a couple contributing $3,000. Indiana also has a 3.23 percent capital gains tax for married couples with $100,000 taxable income.

The baseline tax alpha for Indiana is 4.16 percent. Other states and jurisdictions with high tax alphas include Vermont (2.81 percent), Iowa (2.78 percent), Oregon (2.78 percent), and Washington D.C. (2.67 percent). Savers living in these states and in D.C. who are looking to save for college should almost certainly consider 529 plans (although this says nothing about whether they should use their home state plan or shop out-of-state plans).

The states with the lowest tax alphas are those that have no income taxes. These include Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming—all with a baseline tax alpha of 0.77 percent. The only benefit of investing in 529 plans in these states is the avoidance of federal capital gains taxes.

Other low tax alpha states include North Carolina (1.07 percent), Kentucky (1.04 percent), New Jersey (1.07 percent), Delaware (1.13 percent), and Maine (1.13 percent). Investors in these states with a shorter time horizon or lower contribution amount may find that the reward for using a 529 plan is not worth the potential drawbacks. They may choose instead to save in a taxable account, or to dedicate more savings to retirement plans that will not affect financial aid.

It should be noted that some states offer additional matching benefits that are not included in Table 1. These matching benefits generally apply to lower- and middle-income households and typically provide up to several hundred dollars in matching funds. States with current matching plans include: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Nevada, North Dakota, Tennessee, and West Virginia. The list of these features can be found at savingforcollege.com. Financial planners working with clients in these states should further evaluate how potential matching can affect the total benefit of 529 plans.

Is the Tax Alpha Surmountable?

These results may raise a question for planners and their clients: is the tax alpha worth it? In some cases, the answer is yes. For instance, New Yorkers receive a potentially high deduction with marginal income and capital gain tax rates as high as 8.8 percent. For New Yorkers with a 10-year time horizon and a state income tax rate of 6.33 percent, the tax alpha is greater than 2 percent. It would be difficult for any responsible money manager to suggest that he or she could provide such excess returns, even against a poorly run or high-fee 529 plan.

On the other hand, for residents in states with more limited tax advantages, the decision to use 529 plans is less obvious. Taxable accounts allow for the potential for tax-loss harvesting, potentially lower fees than comparable 529 plans, and greater flexibility of investments.

In Florida, for example, it may be worth the 0.77 percent tax alpha over 10 years for an investor to use a taxable account with a trusted adviser. This analysis does not attempt to measure the costs of 529 plans, but there are certainly a range of potential costs. To the extent that 529 plan fees (all-in) are over 1 percent, it could make sense to use a low-cost adviser or self-managed brokerage account.

Other potential drawbacks are associated with 529 plans. For example, if a child chooses not to use the money in a 529 plan, there is a potential 10 percent penalty on withdrawals of investment earnings, plus investment earnings will be taxed as ordinary income. However, there are typically no “forced” withdrawals, meaning that the owner of a 529 plan may choose to leave unused funds invested either for future qualified beneficiaries (nieces, nephews, grandchildren) or for emergency purposes (at which point the penalty would still apply).

A child may end up not using the entirety of a 529 plan for several reasons, including financial aid, scholarships, or attending a less expensive school than planned. Investments in 529 plans that go unused can be transferred to a sibling without penalty. Exceptions to the penalty rule also include: if the beneficiary dies or becomes disabled; if the student decides to attend a U.S. military academy; or if the student receives a scholarship. However, in these exceptions, the investment earnings will still incur income tax.

Ultimately, choosing a 529 plan over a taxable account is a no-brainer in some states and debatable in others. The optimal strategy would be to accumulate exactly as much as is needed for college in a low-cost, well-diversified 529 plan. For fear of accumulating too much, or perhaps because of investment restrictions or high fees, it may make sense for some savers to use some combination of 529 plans and taxable accounts.

Implications for Financial Planners

For savers who choose to use 529 plans, they must also decide whether to use one of their in-state plans, or to consider plans outside of their home state. In order to make this decision, a client should first determine whether there is a tax incentive to keep the plan in-state. For example, Massachusetts residents receive an income tax deduction up to $2,000 per married couple, but only with in-state 529 plans. With an income tax rate of 5.1 percent, this means that parents planning to contribute $6,000 per year could increase contributions by $102 (5.1 percent x $2,000). This benefit must be weighted again the quality and cost of plans offered in Massachusetts versus the quality and cost of out-of-state plans.

On the other end of the spectrum are clients in states that offer no tax deductions. These clients should consider shopping around because there is no added incentive to stay in-state with their plans. Some states also offer tax parity on 529 plans. This means that in-state tax incentives can be used with out-of-state plans. Clients and advisers should determine on a state-by-state basis whether it makes sense to select an in-state plan or to shop around.

Another practical consideration is the actual tax bracket that a client faces. Many states have graduated tax rates, much like the federal system. To the extent that clients are in a higher or lower tax bracket than assumed in this analysis, it may make more or less sense to use 529 plans. People in higher tax brackets stand to benefit more from 529 plans. For clients in the 20 percent federal capital gains tax bracket, 529 plans become even more preferable (Dynarski 2004). Higher income savers subject to the Medicare surtax have an even greater incentive to use 529 plans.

Finally, 529 plans can be used as an estate planning tool. The “superfunding” loophole allows up to $75,000 to be contributed to a single beneficiary ($150,000 if each spouse in a married couple makes the gift). For grandparents who wish to pass a large bequest to grandchildren, this can be a tax-advantaged strategy for college funding.

Conclusion

The current average annual cost for a four-year private college is about $34,740. Over the last 10 years, the average cost of tuition has risen at a rate of about 3.4 percent per year.9 If tuition inflation continues at this pace, the total cost of tuition of a four-year private college in 10 years will be nearly $200,000. Despite this massive potential cost, fewer than half of parents use 529 plans in order to save for college.10

Financial planners often work with clients across many states. This can make it difficult to assess tax rules for clients in unfamiliar states. The tax advantages of 529 plans can largely be attributed to state-specific rules.

The decision whether or not to use a 529 plan boils down to a few key factors. If your client lives in a state with a sizable income tax deduction and high marginal tax rate, there is a strong incentive to use 529 plans, even if they increase complexity, decrease investment options, and have relatively high fees. For those clients who live in states with no income taxes, it may be worthwhile to evaluate whether the flexibility of a taxable account outweighs the tax advantage of a 529 plan.

Endnotes

- In some cases, it may be worth shopping for out-of-state plans. Benz (2010) discussed when savers should shop around for out-of-state plans, and Acheson and Sayre (2018) ranked various state plans.

- See this paid tool at www.savingforcollege.com/state_tax_529_calculator.

- Recent changes to 529 plan rules allow for up to $10,000 per year to be withdrawn from 529 plans to pay for private primary and secondary education tuition.

- New Hampshire and Tennessee currently impose taxes on interest and dividend income. These taxes are not available for a deduction through a 529 plan contribution.

- Although subject to change, the current applicable estate tax exclusion is $11.4 million, meaning most investors will not produce any out-of-pocket tax consequences even if they contribute more than the gift tax threshold.

- To the extent that annual income or capital gains distributions from holdings are significant, this only further magnifies the tax advantages of 529 plans. However, taxable accounts allow for tax-loss harvesting, which could be an advantage during volatile periods. Moreover, tax-sensitive investors can use ETFs in a taxable account that may have low expense ratios and almost entirely avoid annual capital gains distributions. The underlying assumption in this paper was that all capital gains and income would be taxed at the end of the investment period.

- In reality most savers will not contribute the tax savings to the 529 plan, but it is assumed as much for the purpose of analysis.

- 2.01 percent is not 2.02 percent due to rounding.

- See “Trends in College Pricing 2018,” from CollegeBoard at research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-college-pricing-2018-full-report.pdf. Also see “Consumer Price Index: Tuition, Other School Fees, and Childcare in U.S. City Average, All Urban Consumers,” at fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CUSR0000SEEB.

- See the Sept. 25, 2018 CNBC article by Jessica Dickler, “College 529 Savings Plan Balances Hit an All-Time High,” at cnbc.com/2018/09/25/college-savings-plan-balances-hit-all-time-high.html.

References

Acheson, Leo, and Stefan Sayre. 2018. “Morningstar Names the Best 529 College Savings Plans for 2018.” Morningstar. Available at morningstar.com/articles/889532/morningstar-names-the-best-529-college-savings-plans-for-2018.

Aldeman, Chad. 2011. “Why 529 College Savings Plans Favor the Fortunate.” Education Sector. Available at eric.ed.gov/?id=ED517064.

Alexander, Raquel, and Leann Luna. 2005. “State-Sponsored College 529 Plans: An Analysis of Factors that Influence Investors’ Choice.” Journal of the American Taxation Association. 27 (S-1): 29–50.

Alexander, Raquel M., LeAnn Luna, and Steven L. Gill. 2015. “Does College Savings Plan Performance Matter?” In Advances in Taxation, pp. 76–100. Bingley, U.K.: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Alpert, Benjamin N., Josh Charlson, Kailin Liu, Laura Pavlenko Lutton, and Christina West. 2010. “2010 529 College-Savings Plans: Research Paper and Industry Survey.” Morningstar. Available at news.morningstar.com/pdfs/Morningstar.529.Industry.Survey.11.1.10.pdf.

Benz, Christine. 2010. “Should 529 Investors Stay In-State or Shop Around?” Morningstar. Available at news.morningstar.com/articlenet/article.aspx?id=356658.

Chang, C. Edward, and Thomas M. Krueger. 2018. “529 Plan Investment Advice: Focusing on Equity Concentration and Fees.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (6): 34–43.

Clancy, Margaret, Michael Sherraden, Mark Huelsman, David Newville, and Ray Boshara. 2009. “Toward Progressive 529 Plans: Key Points.” CSD Policy Brief No. 9-76. Center for Social Development and New America Foundation. Available at csd.wustl.edu/09-76.

DeGennaro, Ramon P. 2004. “Asset Allocation and Section 529 Plans.” International Journal of Business 9 (2): 125–132.

Dynarski, Susan. 2004. “Who Benefits from The Education Saving Incentives? Income, Educational Expectations, and the Value of the 529 and Coverdell.” National Tax Journal 57 (2, Part 2): 359–383.

Gardner, Randy, and Leslie Daff. 2017. “Recent 529 Plan Changes Add to Their Advantages.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (4): 36–38.

Hannon, Simona, Kevin B. Moore, Max Schmeiser, Irina Stefanescu. 2016. “Saving for College and Section 529 Plans.” FEDS Notes 2016-02-03, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Available at federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/feds-notes/2016/saving-for-college-and-section-529-plans-20160203.html.

Pressman, Steven, and Robert H. Scott III. 2017. “The Higher Earning in America: Are 529 Plans a Good Way to Save for College?” Journal of Economic Issues 51 (2): 375–382.

Spitzer, John J., and Sandeep Singh. 2001. “The Fallacy of Cookie Cutter Asset Allocation: Some Evidence from New York’s College Savings Program.” Financial Services Review 10 (1-4): 101–116.

Toner, Matthew. 2019. “How Much Is Your State’s 529 Plan Tax Deduction Really Worth?” SavingforCollege.org. Available at savingforcollege.com/articles/how-much-is-your-states-529-plan-tax-deduction-really-worth-733.

Citation

Delorme, Luke. 2019. “College Savers: What Is the Expected Tax Alpha of 529 Plans?” Journal of Financial Planning 32 (11): 44–52.