Journal of Financial Planning: October 2016

Kenneth N. Ryack, Ph.D., CFP®, CPA, is an assistant professor of accounting at the Quinnipiac University School of Business. His research interests include various topics in behavioral finance and behavioral accounting.

Michael Kraten, Ph.D., CPA, is an associate professor of accountancy at the Providence College School of Business. His research interests include theories of investment valuation, behavioral accounting, sustainability frameworks, and negotiation strategies.

Aamer Sheikh, Ph.D., CPA, CR.FA, CFC®, CGMA®, is an associate professor of accounting at the Quinnipiac University School of Business. His research interests include corporate governance issues and executive compensation.

Executive Summary

- An individual’s financial risk tolerance ultimately drives his or her financial decisions and is therefore of critical importance in personal financial planning.

- Two psychometrically valid measures of an individual’s financial risk tolerance are highlighted, and academic research findings on the nine determinants of an individual’s financial risk tolerance are discussed.

- For example, financial risk tolerance tended to increase with the level of the client’s education, income and wealth, and financial knowledge and experience. Financial risk tolerance also appeared to vary with gender, age, and market conditions.

- A framework was developed to organize the nine discrete factors that influence a client’s financial risk tolerance on the basis of foreseeability and manageability to make it easier for financial planners to integrate financial risk tolerance into the financial planning process.

When working with a client to create a long-term financial plan, three important risk factors must be considered: (1) risk need; (2) risk capacity; and (3) financial risk tolerance (Carr 2014; Nobre and Grable 2015).

A client’s risk need is the amount of risk required to meet a particular financial goal (Carr 2014; Nobre and Grable 2015). For example, a young client with a low net worth and moderate income level would have a high risk need if he or she wished to retire at some point in the future with a sizable retirement portfolio.

Risk capacity reflects the client’s ability to absorb a possible financial loss resulting from the financial risk taken (Carr 2014; Nobre and Grable 2015). For example, a young, high net worth client with a sizable income and a long time horizon until retirement has a large risk capacity. Both risk need and risk capacity are fairly objective factors that can be determined by reviewing demographic information about a client such as net worth, income level, and time horizon (Carr 2014).

Financial risk tolerance is a more subjective measure that reflects an individual’s willingness to accept uncertainty related to the outcome of a financial decision (Grable 2000). As an individual’s comfort level with such uncertainty increases, their financial risk tolerance goes up. For example, a consultant comfortable taking on the financial risk associated with starting her own business has a higher risk tolerance than a consultant who would prefer to work for someone else in order to avoid such risk. When applied to an investment context, financial risk tolerance is sometimes referred to as investor risk tolerance and reflects an investor’s willingness to accept investment risk and market volatility (Grable and Lytton 1998). Although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, the term financial risk tolerance was used throughout this article because it is the focus of most of the research studies referenced here and because it can be applied to the financial planning process as a whole. Risk aversion is another term sometimes used instead of financial risk tolerance. Risk aversion represents the inverse of financial risk tolerance. The more risk averse a person is, the lower their comfort level with financial uncertainty.

Research has shown that a portfolio consisting of more risky assets, such as equities, tends to outperform a portfolio consisting of less risky assets, such as bonds and certificates of deposit, over the long term, and thus can lead to greater wealth accumulation for retirement (Hanna and Chen 1997; Siegel and Thaler 1997). Therefore, a financial planner may be tempted to create a financial plan for a client that includes an increasing proportion of financial risk as the client’s time horizon and risk capacity increase. This makes sense because it would help increase the client’s long-term wealth accumulation for retirement. However, a financial planner also needs to be conscious of the client’s financial risk tolerance and incorporate it into the financial plan.

When a planner has a thorough understanding of financial risk tolerance and its determinants, the planner has a better chance of developing an appropriate financial plan that the client will actually follow. Research has shown that an individual’s financial risk tolerance affects their investment behavior (Bailey and Kinerson 2005; Hoffmann, Post, and Pennings 2013, 2015).

If a planner recommends a financial plan containing a portfolio of investments that does not match the client’s financial risk tolerance, the plan may ultimately fail. For example, suppose a financial planner recommends a more risky retirement portfolio containing mostly equities because the client has a long time horizon until retirement and the financial planner knows that the return on equities over time is generally larger than it is for less-risky assets such as bonds and money market instruments. If the client follows the financial planner’s recommendations and invests in such a portfolio, she may maximize her retirement nest egg and retire at her target retirement age. However, if the client is uncomfortable with the recommended investments due to her low financial risk tolerance, then she may not follow the financial planner’s investment recommendations and instead keep her savings in CDs. In this case, the plan fails because the client likely will not have enough funds to retire when she reaches her target retirement age. Another possibility is that she does invest in the recommended investments, but gets nervous during a stock market decline and moves her portfolio to less-risky investments. She may incur losses that could have been avoided if she had waited for the market to turn around.

The need for a financial planner to consider a client’s financial risk tolerance is well documented in the literature and often required to meet various professional standards and regulations. For example, FINRA’s suitability rule (Rule 2111) states that a customer’s risk tolerance must be considered by the financial planner when recommending a transaction or investment strategy. Rule 200-1 of the CFP Board’s practice standards states that “ … the practitioner will need to explore the client’s values, attitudes, expectations, and time horizons as they affect the client’s goals.” (see “Practice Standards 200” at cfp.net/for-cfp-professionals). Although financial risk tolerance is not specifically mentioned, it may be implied that it should be considered when assessing the client’s attitudes.

Just before FINRA 2111 became effective in July 2012, Evensky and Moreschi (2011, p. 30) cited the need for financial planners to understand financial risk tolerance when they wrote: “Because risk tolerance is a key component to providing suitable advice and because regulators will soon require its explicit consideration, it makes sense to review the literature.”

Measuring Financial Risk Tolerance

Care should be taken when selecting an appropriate tool to measure a client’s financial risk tolerance. There is no shortage of financial risk tolerance questionnaires available to planners and their clients. However, analyses have shown that some do not contain questions that lead to an adequate assessment of a client’s true financial risk tolerance (Jacobsen, Speidel, Keshemberg, and Hodapp 2014; Roszkowski, Davey, and Grable 2005).

Roszkowski, Davey, and Grable (2005) suggested that a measurement instrument be rigorously tested and assessed for validity (i.e., it actually measures what it is intended to measure) and for reliability (i.e., it is consistent in its measurement of the underlying construct) using a standard scientific technique known as psychometric testing. A financial planner may not have the resources to psychometrically test their own measure of financial risk tolerance, and therefore may consider using an established measurement instrument that has undergone such testing and has been used extensively in both research and practice. Two such measures include the FinaMetrica® 25-item scale (see www.riskprofiling.com) and the Grable-Lytton 13-item scale (see Gilliam, Chatterjee, and Grable 2010; Grable and Lytton 1999, 2001, 2003; Kuzniak, Rabbani, Heo, Ruiz-Menjivar, and Grable 2015).

A psychometrically valid and reliable measurement instrument is just one tool and it should not be used in isolation. It should serve as an input to a dialogue with the client, but not as a replacement for such a dialogue (Roszkowski, Davey, and Grable 2005). The score such an instrument produces may be used as a base measure of the client’s risk tolerance and incorporated into a broader discussion with the client about various factors that may affect his or her comfort level with and propensity to execute various aspects of a financial plan. To facilitate such a dialogue, it is helpful for a financial planner to also have a basic understanding of the determinants of financial risk tolerance.

Determinants of Financial Risk Tolerance

Research has uncovered a number of variables that appear to influence financial risk tolerance. They include gender, race/ethnic group, age, education level, income and wealth, employment status, financial knowledge/experience, marital status and family relationships, and market conditions and expectations.

Gender. Results from numerous studies suggest that females tend to exhibit lower financial risk tolerance than males (see, for example, Anbar and Eker 2010; Faff, Hallahan, and McKenzie 2011; Gibson, Michayluk, and Van de Venter 2013; Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie 2004; Sung and Hanna 1996; Wong 2011). Researchers have posited two main theories for this: (1) differences in evolutionary biology between females and males; and (2) societal differences in the roles of females and males that have evolved over time (Anbar and Eker 2010; Faff, Hallahan, and McKenzie 2011; Olsen and Cox 2001; Wong 2011).

Race/ethnic group. The research has generally found that Caucasians (Whites) have a higher financial risk tolerance than Blacks and Hispanics (Chang, DeVaney, and Chiremba 2004; Grable and Lytton 1998; Hawley and Fujii 1993; Sung and Hanna 1996; Xiao, Alhabeeb, Gong-Soog, and Haynes 2001; Yao, Sharpe, and Wang 2011). However, some studies found no significant difference in financial risk tolerance based on race/ethnic group (Antonites and Wordsworth 2009; Grable and Joo 2004). Factors may have been at play that mitigated any impact of race/ethnic group. Participants in one study were college business students, and participants in the other study were college faculty and staff. As noted below, higher levels of education are generally associated with higher levels of risk tolerance. This suggests racial/ethnic differences in financial risk tolerance may be mitigated when other determinants of financial risk tolerance are equalized. A recent study by Shin and Hanna (2015) addressed this possibility and found that if households with Black and Hispanic respondents had the same characteristics and risk tolerance as White households, the difference in high return investment ownership was narrowed, but did still exist. Another study found that although Blacks were less likely to own stocks, there was no difference in the portfolio riskiness of Whites and Blacks who owned stocks (Gutter and Fontes 2006).

Age. It is a widely held belief among scholars that financial risk tolerance should decrease with age. This could be because older individuals have less time to recover from potential losses of more risky investments or because changes in our biology as we grow older might cause us to become less willing to take on more risk. Numerous studies have supported the belief that older individuals have lower financial risk tolerance (see, for example, Faff, Hallahan, and McKenzie 2009, 2011; Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie 2003, 2004). However, some studies demonstrated the opposite effect, where financial risk tolerance increased with age (Chang, DeVaney, and Chiremba 2004; Grable 2000; Wang and Hanna 1997; Xiao et al. 2001).

A curvilinear relationship may exist between age and financial risk tolerance. For example, Faff, Mulino, and Chai (2008) found that financial risk tolerance decreased with age up to a point and then increased. In contrast, results from a few other studies showed financial risk tolerance increasing with age up to a point and then decreasing (Gilliam, Chatterjee, and Grable 2010; Riley and Chow 1992; Weagley and Gannon 1991).

Regardless of the precise functional form of the relationship between age and financial risk tolerance, it is important that the client’s age be taken into account when determining the client’s financial risk tolerance, because it may have an impact on a particular client’s financial risk tolerance, and it may interact with other variables in determining a client’s risk tolerance.

Education. A large amount of research across a variety of groups found a significant positive relationship between an individual’s education level and their financial risk tolerance. This could be because more educated individuals are better able to understand and evaluate the relationship between risk and return, and because they have access to more financial resources they can use to offset possible losses incurred from taking on more risk (Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie 2004; Hariharan, Chapman, and Domian 2000; Riley and Chow 1992; Wong 2011). It has also been suggested that the positive relationship between education and financial risk tolerance may be due to the fact that individuals with more income and wealth tend to be better educated (Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie 2004; Riley and Chow 1992). In other words, the education variable may simply be capturing the effects of income and wealth.

Income and wealth. A preponderance of research has found a positive relationship between financial risk tolerance and both wealth and income (see, for example, Chang, DeVaney, and Chiremba 2004; Faff, Hallahan, and McKenzie 2009; Gibson, Michayluk, and Van de Venter 2013; Grable 2000; Grable and Joo 2004; Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie 2004). In other words, as a client’s wealth and income increase, their financial risk tolerance is also likely to increase. Researchers have suggested this positive relationship is due to the fact that individuals with higher levels of wealth and income have a better capacity to absorb any potential losses that may result from more risky investments (Chang, DeVaney, and Chiremba 2004; Faff, Hallahan, and McKenzie 2009, 2011; Grable 2000; Xiao et al. 2001).

Self-employment status. In addition to the positive relationship between financial risk tolerance and wealth/income, research has also found that self-employed individuals displayed higher levels of financial risk tolerance (see, for example, Chang, DeVaney, and Chiremba 2004; Grable and Lytton 1998; Sung and Hanna 1996; Yao and Curl 2011; Yao, Gutter, and Hanna 2005; Yao, Sharpe, and Wang 2011). Although those studies did not offer any specific theories for this result, it may seem logical given the financial risks associated with owning a business.

Financial knowledge and experience. A number of studies incorporated different measures of financial risk and found a significant positive relationship between an individual’s financial risk tolerance and the level of their financial knowledge and experience (Antonites and Wordsworth 2009; Gibson, Michayluk, and Van de Venter 2013; Grable 2000; Grable and Joo 1997, 2004; Ryack 2011). In other words, financial risk tolerance tends to increase with higher levels of financial knowledge and experience. This relationship may exist because individuals with a higher level of financial knowledge and experience generally have more confidence in their analytical and financial decision-making skills, possess a greater understanding of the possible outcomes associated with higher risk, and have stronger coping mechanisms to deal with uncertainties (Grable and Joo 1997; Yao, Sharpe, and Wang 2011).

Marital status and family relationships. Unmarried individuals tend to display higher levels of financial risk tolerance. This might be because they have fewer responsibilities and any loss they incur only affects one individual rather than an entire family (Chaulk, Johnson, and Bulcroft 2003; Faff, Hallahan, and McKenzie 2009, 2011; Faff, Mulino, and Chai 2008; Grable and Joo 2004; Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie 2004; Hawley and Fujii 1993; Van de Venter, Michayluk, and Davey 2012; Wong 2011; Yao, Sharpe, and Wang 2011). Consistent with the gender research previously discussed, studies have found that the male spouse exhibited higher levels of financial risk tolerance than the female spouse within married couples. Studies have further shown that the investing behavior of spouses tended to be correlated with each other. The reason for this correlation is not clear, but it could be that people naturally seek out mates that have a similar financial risk tolerance or financial risk tolerances begin to converge as couples spend more time together (Gilliam, Goetz, and Hampton 2008; Roszkowski, Delaney, and Cordell 2004; Ryack 2011; Sung and Hanna 1998).

Researchers have also investigated how dependents may affect financial risk tolerance. While Ryack (2011) found no correlation between the financial risk tolerance of parents and their college-age children, it is possible that having children may decrease one’s financial risk tolerance. Some researchers have suggested that an increase in dependents results in reduced financial risk tolerance because more resources are needed to meet basic family needs and these resources must be protected from the risk of loss (Anbar and Eker 2010; Chaulk, Johnson, and Bulcroft 2003). In fact, a number of studies found that financial risk tolerance decreased as the number of dependents increased (Chaulk, Johnson, and Bulcroft 2003; Faff, Hallahan, and McKenzie 2009; Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie 2004; Yao, Sharpe, and Wang 2011).

Market conditions and expectations. In general, the research suggests changes in financial risk tolerance are linked to stock market expectations and actual changes in the stock market. For example, Gibson, Michayluk, and Van de Venter (2013) demonstrated that individuals who perceived the stock market to be riskier compared to two years prior had lower average financial risk tolerance scores. They also found higher financial risk tolerance scores for individuals with positive future expectations for the stock market. In addition, a number of studies have shown that investors’ financial risk tolerance increased with rises in market prices and decreased with declines in market prices as measured by indices such as the S&P 500 Index (Grable, Lytton, and O’Neill 2004; Guillemette and Finke 2014; Hoffmann, Post, and Pennings 2013; Yao and Curl 2011; Yao, Hanna, and Lindamood 2004).

However, some additional research found financial risk tolerance to be stable over time, and the impact of stock market swings such as those seen during the global financial crisis was temporary. For example, Gerrans, Faff, and Hartnett (2015) demonstrated that financial risk tolerance remained relatively stable through the global financial crisis. Guillemette and Finke (2014) showed that although financial risk tolerance changed with the market during the global financial crisis, the distance between the lowest and highest financial risk tolerance scores was only 7.1 percent, compared to a 51.7 percent swing in stock prices during the same period. Hoffmann, Post, and Pennings (2013) also found that financial risk tolerance changes during the global financial crisis were temporary, and by the end of the crisis there was no significant change in financial risk tolerance.

Taken as a whole, this research suggests that financial risk tolerance may be elastic with changes in the stock markets, but stable over time. Thus, it is important for a financial planner to periodically reassess their client’s financial risk tolerance. It is also important for a financial planner to stay in contact with clients during periods of market uncertainty and provide reassurances to clients to prevent them from making impulsive decisions during those periods.

A Conversational Framework

The earlier section, “Measuring Financial Risk Tolerance,” addressed the need to use a survey instrument to quantify the overall risk tolerance levels of a client. After this measure is compiled, financial planners may wish to discuss with clients how their current circumstances and future plans impact their financial risk tolerance. It should be noted that the survey measurement and the conversation are complementary activities. The client’s financial risk tolerance score provides an initial assessment. However, financial planners should be continually vigilant about changes in the circumstances and plans of their clients, and should be prepared to discuss the impact of such changes on overall levels of risk tolerance.

The preceding literature review listed the nine significant factors that determine the financial risk tolerance of any client. Financial planners and their clients may find it helpful to use a conversational framework to organize their discussions of the factors. Such a framework can be established in different ways. According to most paradigms of risk management, risk factors are usually assessed on the basis of likelihood and impact. Likelihood refers to the probability that circumstances will foreseeably change in an undesirable direction, and impact refers to one’s ability to manage such circumstances in order to minimize damage.

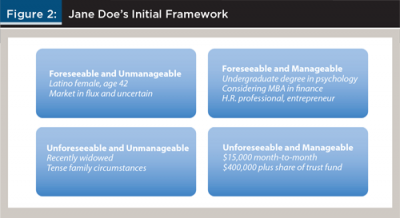

For example, the enterprise risk management guidelines of the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) uses the words “likelihood” and “impact” to describe these assessment concepts (see coso.org/documents/COSO_ERM_ExecutiveSummary.pdf). And the risk maturity model of the Risk and Insurance Management Society (RIMS) uses the analogous words “frequency” and “effectiveness” in the scoring methodology of its value drivers (see riskmaturitymodel.com). For financial planning purposes, the framework in Figure 1 uses the analogous words “foreseeability” and “manageability;” in other words, how easily a client can foresee a change in a factor, and how much confidence a client expresses in her ability to manage its potential impact on her financial status. This framework proposes that financial planners and their clients jointly assign each of the nine factors to one of the four categorical quadrants that are defined by the intersection of these two considerations.

The decision to place any given factor in a specific quadrant varies from client to client. For certain factors, the decision also varies with the passage of time and its resulting impact on personal status. For instance, a client who is a confirmed bachelor at age 35 might decide to seek a spouse at age 45. If uncertain about his prospects, such a client may shift his marital status from foreseeable and manageable to unforeseeable and manageable. It should be noted that foreseeability is analogous to predictability. For instance, if a client is 100 percent certain that he will be able to predict his future age and race/ethnic group at any given point in the future, both factors will be foreseeable even though age is variable while race/ethnic group is fixed. When conversing with clients, financial planners may find it useful to discuss the aforementioned nine factors, and to offer to help their clients decide how to categorize each factor within the framework of Figure 1. By using this framework, financial planners may be able to learn quite a bit about the perspectives of their clients.

A Hypothetical Illustration

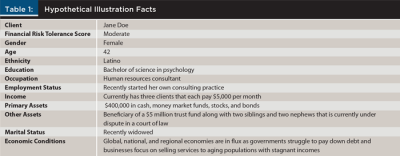

To demonstrate the efficacy of this approach, assume that John Smith, CFP®, conducts an introductory interview with a potential client, Jane Doe, and asks her to complete a financial risk tolerance survey. Table 1 presents a summary of the information John has collected from Jane. After reviewing the information together, John and Jane discuss the framework and customize it to Jane’s situation, as shown in Figure 2.

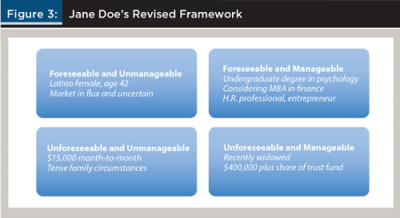

Jane then volunteers that she is considering an admission offer to an MBA program in finance at her local state college. She also tells John that she believes that her marital status has become unforeseeable and manageable now that she is single again. She also mentions that she barely knows her clients, and thus she currently considers the risk of losing her monthly retainer fees to be unforeseeable and unmanageable. John and Jane jointly modify the framework to address these considerations (see Figure 3), and John consults the review of the academic literature that has been included in this article. He notes that the possibility of earning an MBA degree in finance, of establishing a successful entrepreneurial business, and of winning a significant share of the trust fund should each tend to make Jane more risk tolerant in the future. However, given the absence of these factors at the present time, she may be less risk tolerant. When John mentions this to Jane, she agrees that the findings in the academic literature regarding the impact of education, financial knowledge, and wealth on risk tolerance are relevant to her situation. He observes in passing that all three of these factors fall within the “manageable” column of the framework.

Based on this discussion, John and Jane conclude their planning activities by agreeing on the following:

Given that Jane is facing a number of life issues that generate unforeseeable and/or unmanageable risk and uncertainty, she should consider adopting a flexible investment strategy that is slightly more risk averse than theoretically called for by her “moderate risk tolerance level” survey profile. Such a strategy would permit Jane to adjust her portfolio as her situation changes over time.

Given that Jane hopes to manage her life in a manner that may shift her into a position of greater risk tolerance in the future, she should review information about more risky investment strategies for further consideration.

Based on this hypothetical illustration, it can be observed how the four-quadrant model can assist a financial planner in evaluating and revising their initial assessment of client financial risk tolerance levels and potential asset allocation scenarios.

For instance, assume that after reviewing Jane’s financial risk tolerance score and the information in her client questionnaire, John concludes that she should be placed in a mix of 60 percent common stock and 40 percent corporate bond investments.

If after further discussion, John determines that most of Jane’s personal risks fall in the “foreseeable and manageable” quadrant of the framework, he might recommend changing the 60/40 ratio to a 70/30 ratio. Conversely, if most of her risks fall in the “unforeseeable and unmanageable” quadrant, a change to a 50/50 ratio might be more appropriate. If most of Jane’s risks fall in the “foreseeable and unmanageable” or “unforeseeable and manageable” quadrants, then John might recommend staying put at a 60/40 ratio, or at most perhaps changing it to 55/45 ratio.

The value of the model lies in its ability to supplement the equity-to-debt allocation decision that is initially recommended by a standard client questionnaire and financial risk tolerance survey. Although a client questionnaire and financial risk tolerance survey establish an initial baseline recommendation, the framework model can help the planner customize the recommendation to reflect the client’s unique set of life circumstances.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to provide a synopsis of the academic literature regarding the primary factors that impact financial risk tolerance and to present a framework for integrating consideration of financial risk tolerance into the financial planning process. Based on the analysis of the existing academic research, nine discrete factors should be considered during conversations with clients. Research has found that the determinants of financial risk tolerance include the client’s gender; race or ethnic group; age; education; income and wealth; self-employment status; financial knowledge and experience; marital status and family relationships; and market conditions and expectations. All of these factors are suitable topics for client conversations.

A framework that organizes these factors on the basis of foreseeability and manageability was developed and presented. Pairing the considerations of foreseeability and manageability is useful because it describes the two underlying features of risk by employing terminology that is likely meaningful and understandable to clients. The framework is not designed to produce discrete data in regard to financial risk tolerance, and thus cannot supplant the surveys and questionnaires that have been developed for that purpose. Instead, the framework is designed to supplement surveys and questionnaires by providing financial planners with a conversational methodology that identifies relevant citations and readings from the academic literature. Just as a variety of questionnaires and other survey instruments have emerged over time to quantify financial risk tolerance, different versions of the framework presented here may eventually be customized for investors at different stages of their lives.

Astute financial planners should be able to benefit from understanding academic research findings and incorporating the content into their client discussions. Such discussions are important because, if the financial risk inherent in a long-term financial plan is not aligned with the client’s financial risk tolerance, then the client may not follow through with the plan and it may ultimately fail. Thus, it is essential that financial planners understand the determinants of financial risk tolerance and assess their client’s financial risk tolerance when developing a long-term financial plan.

References

Anbar, Adem, and Melek Eker. 2010. “An Empirical Investigation for Determining of the Relation between Personal Financial Risk Tolerance and Demographic Characteristic.” Ege Academic Review 10 (2): 503–523.

Antonites, A.J., and R. Wordsworth. 2009. “Risk Tolerance: A Perspective on Entrepreneurship Education.” Southern African Business Review 13 (3): 69–85.

Bailey, Jeffrey, and Chris Kinerson. 2005. “Regret Avoidance and Risk Tolerance.” Financial Counseling and Planning 16 (1): 23–28.

Carr, Nicholas. 2014. “Reassessing the Assessment: Exploring the Factors that Contribute to Comprehensive Financial Risk Evaluation.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, accessed July 25, 2016, at krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/17283.

Chang, Chia-Chi, Sharon A. DeVaney, and Sophia T. Chiremba. 2004. “Determinants of Subjective and Objective Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Personal Finance 3 (3): 53–67.

Chaulk, Barbara, Phyllis J. Johnson, and Richard Bulcroft. 2003. “Effects of Marriage and Children on Financial Risk Tolerance: A Synthesis of Family Development and Prospect Theory.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 24 (3): 257–279.

Evensky, Harold, and Robert W. Moreschi. 2011. “Understanding Risk Tolerance to Remain Compliant.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (7): 28–30.

Faff, Robert, Terrence Hallahan, and Michael McKenzie. 2009. “Nonlinear Linkages between Financial Risk Tolerance and Demographic Characteristics.” Applied Economics Letters 16 (13): 1,329–1,332.

Faff, Robert, Terrence Hallahan, and Michael Mc-Kenzie. 2011. “Women and Risk Tolerance in an Aging World.” International Journal of Accounting and Information Management 19 (2): 100–117.

Faff, Robert, Daniel Mulino, and Daniel Chai. 2008. “On the Linkage between Financial Risk Tolerance and Risk Aversion.” The Journal of Financial Research 31 (1): 1–23.

Gerrans, Paul, Robert Faff, and Neil Hartnett. 2015. “Individual Financial Risk Tolerance and the Global Financial Crisis.” Accounting and Finance 55 (1): 165–185.

Gibson, Ryan, David Michayluk, and Gerhard Van de Venter. 2013. “Financial Risk Tolerance: An Analysis of Unexplored Factors.” Financial Services Review 22 (1): 23–50.

Gilliam, John, Swarn Chatterjee, and John E. Grable. 2010. “Measuring the Perception of Financial Risk Tolerance: A Tale of Two Measures.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 21 (2): 30–43.

Gilliam, John E., Joseph W. Goetz, and Vickie L. Hampton. 2008. “Spousal Differences in Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 19 (1): 3–11.

Grable, John E. 2000. “Financial Risk Tolerance and Additional Factors that Affect Risk Taking in Everyday Money Matters.” Journal of Business and Psychology 14 (4): 625–630.

Grable, John E., and So-hyun Joo. 1997. “Determinants of Risk Preference: Implications for Family and Consumer Science Professionals.” Family Economics and Resource Management Biennial 2: 19–24.

Grable, John E., and So-hyun Joo. 2004. “Environmental and Biopsychosocial Factors Associated with Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 15 (1): 73–82.

Grable, John E., and Ruth H. Lytton. 1998. “Investor Risk Tolerance: Testing the Efficacy of Demographics as Differentiating and Classifying Factors.” Financial Counseling and Planning 9 (1): 61–73.

Grable, John E., and Ruth H. Lytton. 1999. “Financial Risk Tolerance Revisited: The Development of a Risk Assessment Intstrument.” Financial Services Review 8 (3): 163–181.

Grable, John E., and Ruth H. Lytton. 2001. “Assessing the Concurrent Validity of the SCF Risk Tolerance Question.” Financial Counseling and Planning 12 (2): 43–54.

Grable, John E., and Ruth H. Lytton. 2003. “The Development of a Risk Assessment Instrument: A Follow-Up Study.” Financial Services Review 12 (3): 257–274.

Grable, John E., Ruth H. Lytton, and Barbara O’Neill. 2004. “Projection Bias and Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Behavioral Finance 5 (3): 142–147.

Guillemette, Michael, and Michael Finke. 2014. “Do Large Swings in Equity Values Change Risk Tolerance?” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (6): 44–50.

Gutter, Michael S., and Angela Fontes. 2006. “Racial Differences in Risky Asset Ownership: A Two-Stage Model of the Investment Decision-Making Process.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 17 (2): 64–78.

Hallahan, Terrence, Robert Faff, and Michael McKenzie. 2003. “An Exploratory Investigation of the Relation between Risk Tolerance Scores and Demographic Characteristics.” Journal of Multinational Financial Management 13 (4-5): 483–502.

Hallahan, Terrence, Robert Faff, and Michael McKenzie. 2004. “An Empirical Investigation of Personal Financial Risk Tolerance.” Financial Services Review 13 (1): 57–78.

Hanna, Sherman, and Peng Chen. 1997. “Subjective and Objective Risk Tolerance: Implications for Optimal Portfolios.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 8 (2): 17–26.

Hariharan, Govind, Kenneth S. Chapman, and Dale L. Domian. 2000. “Risk Tolerance and Asset Allocation for Investors Nearing Retirment.” Financial Services Review 9 (2): 159–170.

Hawley, Clifford B., and Edwin T. Fujii. 1993. “An Empirical Analysis of Preferences for Financial Risk: Further Evidence on the Friedman-Savage Model.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 16 (2): 197–204.

Hoffmann, Arvid O. I., Thomas Post, and Joost M. E. Pennings. 2013. “Individual Investor Perceptions and Behavior During the Financial Crisis.” Journal of Banking and Finance 37 (1): 60–74.

Hoffmann, Arvid O. I., Thomas Post, and Joost M. E. Pennings. 2015. “How Investor Perceptions Drive Actual Trading and Risk-Taking Behavior.” Journal of Behavioral Finance 16 (2): 94–103.

Jacobsen, Brian J., Peter Speidel, Travis L. Keshemberg, and Ryan Hodapp. 2014. “Measure and Manage Risk Tolerance More Effectively.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (5): 20–25.

Kuzniak, Stephen, Abed Rabbani, Wookjae Heo, Jorge Ruiz-Menjivar, and John E. Grable. 2015. “The Grable and Lytton Risk-Tolerance Scale: A 15-Year Retrospective.” Financial Services Review 24 (2): 177–192.

Nobre, Liana Holanda N., and John E. Grable. 2015. “The Role of Risk Profiles and Risk Tolerance in Shaping Client Investment Decisions.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 69 (3): 18–21.

Olsen, Robert A., and Constance M. Cox. 2001. “The Influence of Gender on the Perception and Response to Investment Risk: The Case of Professional Investors.” The Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets 2 (1): 29–36.

Riley, William B., and Victor K. Chow. 1992. “Asset Allocation and Individual Risk Aversion.” Financial Analysts Journal 48 (6): 32–37.

Roszkowski, Michael J., Michael M. Delaney, and David M. Cordell. 2004. “The Comparability of Husbands and Wives on Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Personal Finance 3 (3): 129–144.

Roszkowski, Michael J., Geoff Davey, and John E. Grable. 2005. “Insights from Psychology and Psychometrics on Measuring Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Financial Planning 18 (4): 66–71.

Ryack, Kenneth. 2011. “The Impact of Family Relationships and Financial Education on Financial Risk Tolerance.” Financial Services Review 20 (3): 181–193.

Shin, Su Hyun, and Sherman D. Hanna. 2015. “Decomposition Analyses of Racial/Ethnic Differences in High-Return Investment Ownership after the Great Recession.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 26 (1): 43–62.

Siegel, Jeremy J., and Richard H. Thaler. 1997. “Anomalies: The Equity Premium Puzzle.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 11 (1): 191–200.

Sung, Jaimie, and Sherman Hanna. 1996. “Factors Related to Risk Tolerance.” Financial Counseling and Planning 7: 11–20.

Sung, Jaimie, and Sherman Hanna. 1998. “The Spouse Effect on Participation and Investment Decisions for Retirement Funds.” Financial Counseling and Planning 9 (2): 47–59.

Van de Venter, Gerhard, David Michayluk, and Geoff Davey. 2012. “A Longitudinal Study of Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (4): 794–800.

Wang, Hui, and Sherman Hanna. 1997. “Does Risk Tolerance Decrease with Age?” Financial Counseling and Planning 8 (2): 27–31.

Weagley, Robert O., and Coleen F. Gannon. 1991. “Investor Portfolio Allocation.” Financial Counseling and Planning 2: 131–153.

Wong, Alan. 2011. “Financial Risk Tolerance and Selected Demographic Factors: A Comparative Study in Three Countries.” Global Journal of International Business Research 5 (5): 1–12.

Xiao, Jing J., M. J. Alhabeeb, Hong Gong-Soog, and George W. Haynes. 2001. “Attitude Toward Risk and Risk-Taking Behavior of Business-Owning Families.” The Journal of Consumer Affairs 35 (2): 307–325.

Yao, Rui, and Angela L. Curl. 2011. “Do Market Returns Influence Risk Tolerance? Evidence from Panel Data.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 32 (3): 532–544.

Yao, Rui, Michael S. Gutter, and Sherman D. Hanna. 2005. “The Financial Risk Tolerance of Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 16 (1): 51–62.

Yao, Rui, Sherman D. Hanna, and Suzanne Lindamood. 2004. “Changes in Financial Risk Tolerance, 1983–2001.” Financial Services Review 13 (4): 249–266.

Yao, Rui, Deanna L. Sharpe, and Feifei Wang. 2011. “Decomposing the Age Effect on Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (6): 879–887

Citation

Ryack, Kenneth N., Michael Kraten, and Aamer Sheikh. 2016. “Incorporating Financial Risk Tolerance Research into the Financial Planning Process.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (10): 54–61.