Journal of Financial Planning: October 2021

Executive Summary:

- Purpose: Research across fields suggests that the Big Five personality traits (O.C.E.A.N.) predict individual behaviors including various financial outcomes. However, O.C.E.A.N. as a measuring tool has not caught on in the academic or applied financial planning field as extensively as it has in other disciplines. The purpose of this paper is to be the first to examine the relationship between the Big Five personality traits (O.C.E.A.N.) and four regularly collected financial outcomes—financial literacy, financial risk tolerance, income, and net worth—using a single data set. The correlational format shows the potential predictive ability of personality on various financial behaviors that is succinct and easy to understand.

- Hypothesis: The research hypothesis is that O.C.E.A.N is a significant predictor of financial outcomes. Specifically, 14 out of a possible 20 correlations between O.C.E.A.N. and financial literacy, financial risk tolerance, income, and net worth will be significant.

- Methods: Personality, financial literacy, income, and net worth were collected using a significantly powered current MTurk sample (n=412) representing the U.S. population. Correlations and OLS regressions were run controlling for age, gender, and education to test the relationship between the variables.

- Findings: 16 out of a possible 20 correlations between O.C.E.A.N. and financial literacy, financial risk tolerance, income, and net worth were significant, though some were different than hypothesized. Specifically, this study was the first to find that extraversion correlated positively with financial risk-taking and income but negatively with financial literacy. There was no significant relationship with net worth. Conscientiousness correlated positively with financial literacy, income, and net worth, but negatively with financial risk tolerance. Neuroticism correlated negatively with financial literacy, income, and net worth. These findings contribute to the financial planning field by demonstrating that O.C.E.A.N. can be simply and systematically collected from individuals—much like risk tolerance—which adds insight into specific financial behaviors.

- Possible Research Directions: Much like the systematic adoption of risk tolerance, the academic field of financial planning can be advanced by collecting robust personality data using the O.C.E.A.N. framework. This will allow for the generalization of findings from other fields over to financial planning. To assist researchers, the University of Michigan should consider adding robust measures of financial risk tolerance and personality to its valuable Health and Retirement Study. In addition, practicing financial professionals should consider collecting O.C.E.A.N. data on clients to gain additional insights into clients’ behaviors over and above standalone risk tolerance.

Jim Exley, CFP®, is a doctoral student at the University of Georgia, where he studies the interaction of wealth, personality, and financial education. He has had over 10,000 one-on-one meetings with clients, leveraging his understanding of personality science to support their financial success and well-being.

Patrick Doyle earned his Ph.D. in social and personality psychology at the University of Georgia using advanced statistical approaches to study media, fame, and language. His interest in financial research centers around the way people talk about money. He works as a user experience researcher at SiriusXM + Pandora.

Michael Snell is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia, where his studies focus on how people use the internet to manage goals and relationships. He currently works as a consultant and user researcher on the Microsoft Money team based in Redmond, Washington.

W. Keith Campbell, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at the University of Georgia, where he uses tools of personality science to understand leadership, social media, decision-making, and wealth. He has written multiple popular books about personality as well as a best-selling academic textbook, Personality Psychology: Understanding Yourself and Others. Dr. Campbell has been featured in the New York Times, The Today Show, and The Joe Rogan Experience podcast.

NOTE: Please click on images below for PDF versions.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Americans, on average, consistently rate money and finances as one of their top causes of anxiety (APA 2017). The latest “National Financial Capability Study” (FINRA 2021) indicates that Americans exhibit a low level of financial literacy and have difficulty applying financial decision-making skills to real-life situations. Yet despite having received little or no education in the context of making financial decisions, the majority of working Americans are required to plan for their financial futures (U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics n.d.) and are regularly asked to make investment decisions. While it is true that two-thirds of American employers offer their employees financial education, this education tends to produce marginal results (Fernandes, Lynch, and Netemeyer 2014). In an attempt to better understand why some individuals are better with financial behavior than others, this study focused on the roles played by the Big Five (O.C.E.A.N.) personality traits in predicting individual outcomes related to (1) financial literacy, (2) financial risk tolerance, (3) income, and (4) net worth. Eleven of the 14 hypotheses were supported, and 16 of the 20 correlations were significant. OLS regressions and correlations tell a similar story. Indeed, O.C.E.A.N. has much to offer the financial industry.

Trait models of personality—the idea that individual personality traits can be assessed reliably, lie on a continuum, relate meaningfully to other traits, and are stable across time and situations—have been widely accepted in the field of psychology. Of the trait models, the five-factor model, or Big Five model (O.C.E.A.N.), is of central importance because it captures a broad level of traits (hence the name “Big”) and at a useful level of specificity (there are variants from the Big One to a “Medium 10,” but the five-factor model has shown to be most useful). However, the mention of personality in consumer research “triggers associations of armchair theorizing or atheoretical empiricism” (Baumgartner 2002). This has led to personality remaining on the periphery, instead of the core of individual consumer and financial research (Mendelsohn 1993). In 2002, Baumgartner (2002) described personality research in the consumer context as being in a “sorry state.” While financial personality research has increased in recent years, many using the Big Five (e.g., Asebedo et al 2019; Nabeshima and Seay 2015; Pinjisakikool 2018; Hoffman and Risse 2020; Thanki, Goyal, and Junare 2020), researchers have not settled on a consistent personality measure, occasionally even using categorical measures such as “Type A” and “Type B” (Thanki, Karani, and Goyal 2020; Grable 2000) and Myers–Briggs (Gakhar and Prakash 2017). Using a well-established personality model like the Big Five is important because it allows research across fields to connect. Big Five personality is used in organizational science, clinical psychology and psychiatry, and management, among many others. Constructs like “Type A” don’t have contemporary research.

With the overarching goal of encouraging the field to adopt Big Five measurements, the purpose of the present research is to provide a more complete and concise exploration of the direct link between Big Five personality and various financial outcomes. This paper accomplishes this by synthesizing previous cross-discipline research from psychology and finance by collecting and testing a robust and comprehensive personality measure—O.C.E.A.N.—used in each of these fields, though less often in personal finance. The correlational design of this study provides a straightforward link between continuous personality measures and continuous financial outcomes that is immediately understandable and available for use in the language and practices of planners in the field. In addition, this paper answers Nabeshima and Seay’s (2015) call for a deeper exploration into the link between personality—specifically extraversion, financial risk tolerance, and net worth. Finally, this paper opens the door for researchers and advisers to view financial outcomes and behaviors directly through the lens of O.C.E.A.N. personality traits. The industry-standard self-reported risk tolerance, plus a dependable self-reported personality measure, potentially expands the predictive ability of the information gathered by researchers and advisers with only a small amount of additional effort.

More granularly, this study uses the Big Five model of personality, currently the most well-established and robust model in the field of psychology, and four standard measures of financial performance: (1) financial literacy—the ability to understand and apply financial management skills; (2) risk tolerance—how comfortable individuals feel investing in risky investments; (3) income—the amount of money earned each year; and (4) wealth—an individual’s net worth, which is defined as assets minus liabilities. It is hypothesized—based on the following literature review—that the five key aspects of personality have important relationships with variables of interest for financial planning professionals. In other words, people with specific traits, easily identifiable by financial planners but not often included in formal financial planning fact-finding, will be better or worse at developing and maintaining positive financial outcomes. As it relates to an individual’s financial behavior, several lines of research have examined the links between personality and financial performance. Before reviewing the link between personality and financial performance, it is important to define personality and outline O.C.E.A.N.’s theoretical framework.

Theoretical Framework

McAdams and Pals (2006) defined personality as “. . . an individual’s unique variation on the general evolutionary design for human nature, expressed as a developing pattern of dispositional traits, characteristic adaptations, and integrative life stories, complexly and differently situated in culture.” Thus, the McAdams and Pals (2006) personality framework can be seen as an overarching theory of personality that includes traits, environment and learned behaviors, and life narrative. This study focused on the trait portion of personality. Traits describe a stable pattern of behavior, motivation, emotion, and cognition that can be observed in any sociocultural context (DeYoung 2011). While there are scores of models of individual differences, the five-factor model, or Big Five personality model (Costa and McCrae 1992; Digman 1997; Goldberg 1993; John and Srivastava 1999), is the most widely used system for categorizing personality traits. There are over 3 million peer-reviewed, published research articles using Big Five, just over 100,000 for Myers–Briggs, and just over 6,000 for the Enneagram. Unlike systems often used outside of the field of psychology—like the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) or the Enneagram—measurements of the Big Five allow researchers to measure the level of a trait an individual has and correlate this value with any outcome of interest. It does not assign individuals to personality “types.”

The Myers–Briggs is a very useful and popular measure of personality for trainings; it is simple to sort people into types or buckets and then compare the people in all the different types. Essentially, the use of types magnifies differences between groups. Exaggerating personality differences can be useful pedagogically, but it has three problems for researchers. First, there are few actual “types” or taxa in personality—the subfield of taxometrics has examined this in multiple ways and estimates are that around 15 percent contain “types” (Haslam, Holland, and Kuppens 2012). Second, using types is practically more challenging. Instead of simple correlations, you must use complex ANOVAs, dummy coding, or nonparametric statistics. This means lost statistical power and difficulty in interpretation. Finally, Big Five personality is widely used across the different social and behavioral sciences. Using the Big Five allows those bridges to be built; type measures or outdated trait measures do not. To put a fine point on it, the same personality profile you see in an options trader is likely to be reflected in relationship choices, consumption decisions, and health outcomes including psychiatric conditions, but each of these outcomes is studied in a different academic area.

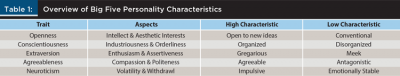

Big Five personality separates dispositional traits into five broad domains: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (O.C.E.A.N.). Each Big Five trait contains six facets (Goldberg 1999). Across those facets, DeYoung, Quilty, and Peterson (2007) found two distinct aspects—in other words, an intermediate level of personality between traits and facets.

Openness contains the facets of fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, actions, ideas, and values. Openness is often associated with intellect and is characterized as a person being interested in new ideas. The two distinct aspects of openness are intellect and aesthetic openness (DeYoung et al. 2007). Practically—on a scale of opposites—“O” has “open to new ideas” on one end of the scale and “conventional” on the other.

Conscientiousness is divided into the facets of competence, order, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, and deliberation. Conscientiousness is often associated with hard work and discipline. The two distinct aspects of conscientiousness are industriousness and orderliness (DeYoung et al. 2007). Practically, “C” has “organized” on the high side of the scale and “disorganized” on the low side (Judge, Rodell, Klinger, Simon, and Crawford 2013).

Extraversion is divided into the facets of warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement seeking, and positive emotions. Extraversion is often associated with risk-taking behaviors such as drinking and aggressive driving (Chapman and Goldberg 2017). The two distinct aspects of extraversion are enthusiasm and assertiveness (DeYoung et al. 2007). “E” is contrasted by “gregariousness” and “meekness” (Judge et al. 2013).

Agreeableness is divided into trust, straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, modesty, and tendermindedness. Agreeableness is often associated with being nice. The two aspects of agreeableness are compassion and politeness (DeYoung et al. 2007). “A” is just as it sounds, with “agreeable” on the high side contrasted with “antagonistic” or “argumentative” on the low side (Judge et al. 2013).

Neuroticism (sometimes called emotional stability to reflect the opposite pole) is divided into anxiety, angry hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsiveness, and vulnerability. Neuroticism is often associated with impulsivity and a lack of emotional stability. The two aspects of neuroticism are volatility and withdrawal (DeYoung et al. 2007). Practically, individuals high in “N” are “impulsive” or “unpredictable” on the high end of the scale, contrasted by those who are “emotionally stable” on the low end of the scale (Judge et al. 2013).

Literature Review

A small body of research has investigated the relationship between the Big Five traits and financial variables, with most of the research focused on the utility of extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism for predicting income (Judge, Higgins, Thorensen, and Barrick 1999; Duckworth, Weir, Tsukayama, and Kwok 2012). While income is certainly an aspect of an individual’s financial success, this study adds to the research by exploring outcomes that are associated with converting income into wealth.

Financial Literacy. In a study of 149 college students across two locations, Killins (2017) found that conscientiousness had a positive relationship with financial literacy while extraversion had a negative relationship. Similarly, Pinjisakikool (2018) found the same negative relationship between extraversion and financial literacy. However, there was no relationship between conscientiousness and financial literacy. Yet intellect (an aspect of openness) did have a positive relationship.

Financial Risk Tolerance. In the financial profession, there is a legal mandate to assess risk tolerance before individuals can invest. Regulations have been enacted by the government and applied in the financial services profession to ensure that clients’ financial needs and preferences are accounted for, including their financial risk tolerance (DOL n.d.). The self-reported financial risk-tolerance questionnaire has thus become a primary tool in the financial services profession for constructing investment portfolios and managing investor behavior. Based on this, there is an entire literature on assessing risk tolerance and an individual’s ability to deal with risky assets such as stocks. On a general level, Big Five and nonfinancial specific risk tolerance research is extensive. In a 2014 meta-analysis of 22 studies and 2,120 participants, Lauriola, Panno, Levin, and Lejuez (2014) found a positive correlation between risk-taking and sensation seeking—a sub-facet of extraversion—and a small correlation between risk-taking and impulsivity—a sub-facet of neuroticism. A particularly interesting study by Nicholson, Soane, Fenton-O’Creevy, and William (2005) found that overall risk-taking can be predicted by high scores in extraversion and openness and low scores in neuroticism, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. The Nicholson et al. (2005) study concluded that demographics, personality, and domain type can be combined to create three categories of risk-takers: (1) stimulation seekers, (2) goal achievers, and (3) risk adapters.

Despite calls for increased research on the direct relationship between personality and financial risk-taking (Grable and Joo 2004), few studies have been completed. Mayfield, Perdue, and Wooten (2008) found openness to be negatively correlated with financial risk aversion—the opposite of risk tolerance—and neuroticism to be positively correlated with risk aversion. In an unpublished dissertation, Seidor (2018) found a positive correlation between extraversion and openness and financial risk-taking. Seidor (2018) also found a negative correlation between neuroticism and financial risk-taking. Bortoli, Costa, Goulart, and Campara (2019) found individuals high in openness having higher risk-taking behavior. Recently, risk aversion was found to have a negative impact on long-term investment intention (Thanki, Goya, and Junare 2020).

While some assessments of risk tolerance have been thoroughly researched (Grable and Lytton 1999), the starting point for this practice is in law, not science. In addition, risk-tolerance questionnaires are often developed by financial institutions, which sometimes leads to results that are biased in favor of the institution’s interests rather than the client’s needs (Investor.gov n.d.). Also of note is that risk tolerance is somewhat elastic and changeable (Grable, Lytton, and O’Neill 2004) and open to manipulation (Thaler and Johnson 1990). While the primary use of the financial risk-tolerance questionnaire has been to determine portfolio composition, the current study is the first to explore the relationship between personality, risk tolerance, financial literacy, income, and net worth using robust personality and risk-tolerance measures in one data set.

Income. Research on personality traits and income is extensive. The O.C.E.A.N. traits have been a fairly consistent predictor of income (Borghans, Duckworth, Heckman, and ter Weel 2008). A search of peer-reviewed personality research and income studies yields over 400,000 results. In their seminal paper with over 2,700 citations to date, Judge et al. (1999) found significant correlations between income and conscientiousness (C) (.34), neuroticism (N) (–.32), and extraversion (E) (.24). While C, E, and N have the most reliable correlations with income, each of the five traits has been shown in various studies to have some type of relationship. Openness is generally found to have a slight positive relationship with income. Conscientiousness is generally found to have a reliable positive relationship with income. Extraversion is generally shown to have the highest positive relationship with income. Agreeableness is generally found to have a negative relationship with income. Neuroticism is generally found to have a consistent negative relationship with income (Judge et al. 1999; Borghans et al. 2008; Heineck 2011; Duckworth et al. 2012; Nandi and Nicoletti 2014; Prevoo and ter Weel 2015). Of particular interest, in a study of 4,642 twin pairs, Maczulskij and Viinikainen (2018) found that extraversion was related to higher permanent earnings, whereas neuroticism was related to lower permanent earnings.

Net worth. The literature on personality and net worth is emerging but limited. In the most extensive study on personality and financial outcomes to date, Duckworth et al. (2012) used a net-worth measure in their analysis of the Health and Retirement Survey data. They found openness, conscientiousness, and extraversion to have a positive relationship with net worth, neuroticism to have a negative relationship, and agreeableness to have no relationship with net worth. Of particular note was the average age of the participants in the study: 68. Less is known about younger cohorts. Nabeshima and Seay (2015) showed that extraversion and conscientiousness are positively associated with net worth, while agreeableness is negatively associated with net worth. Related to net worth, Letkiewicz and Fox (2014) reported that conscientiousness is a reliable predictor of asset accumulation among young Americans. Asebedo et al. (2019) found that high extraversion and high conscientiousness indirectly lead to increased savings behavior and high openness, and high neuroticism indirectly leads to lower savings behavior. Individuals high in extraversion have also been shown to have higher levels of consumer debt (Brown and Taylor 2014).

In summary, high Os are well-read and not afraid of risk. Interestingly, high Os’ creativity is not consistently known for higher incomes. High Cs like to learn, are high earners, and are good savers with higher net worth. High Es are high earners who like risk—but do they convert their income and risk-taking into net worth? High As are nice, but don’t like risk. Finally, high Ns are less open to new ideas, earn lower incomes, aren’t risk takers, and have lower net worth.

Current Study

Based on this body of literature, it was hypothesized that there would be relationships between important financial variables and individual Big Five traits. Specifically, financial literacy would be positively associated with Openness (H1A) and Conscientiousness (H1B) and negatively with Neuroticism (H1C). Financial risk tolerance would be positively associated with Openness (H2A) and Extraversion (H2B) and negatively with Conscientiousness (H2C), Agreeableness (H2D), and Neuroticism (H2E). Income would be positively associated with Conscientiousness (H3A) and Extraversion (H3B) and negatively associated with Neuroticism (H3C). Finally, net worth would be associated positively with Conscientiousness (H4A) and Extraversion (H4B) and negatively with Neuroticism (H4C).

Sample and Procedures

The total sample for this study included 482 participants representative of the U.S. population recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). MTurk is an online crowdsourcing platform that enables researchers to connect with a vast pool of online research prospects in exchange for compensation. MTurk has been validated as a data collection resource and its respondents have been shown to be representative of the general population (Goodman, Cryder, and Cheema 2013; Paolacci and Chandler 2014).

Sixty-eight participants were eliminated due to missing data and failing to pass attention checks. To remove outliers, net worth was capped at $5 million, which removed two additional participants. The total analytic sample was 412 participants. Participants were U.S. citizens over the age of 21 who completed approximately 26 minutes of questions and scales and were compensated $1 for their time. It contained 186 females (45 percent). Slightly less than half of the participants held a bachelor’s degree (49 percent) and 222 (54 percent) were married. The average age of participants was 37 years (M = 36.64, SD = 11.09). The sample was 71 percent White, 21 percent African American/Black, 5 percent Asian, and 3 percent Hispanic/Latino. The average income was $45,000 (M = $44,945, SD = $39,198), which is near the 2019 median of $41,537. The average net worth of participants was $115,000 (M = $114,668, SD = $249,512), which is also near the 2017 median of $104,000 (U.S. Census Bureau n.d.).

Measures

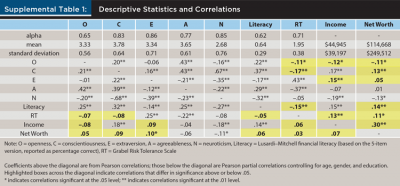

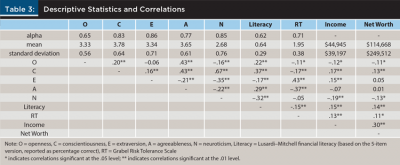

Big Five Personality. Personality was measured with the NEO-IPIP 60 (Maples-Keller et al. 2017). The NEO-IPIP 60 is a self-reported personality measure that identifies the five dimensions of personality. The NEO-IPIP 60 consists of 60 items—12 for each dimension of personality—that asks participants how much a phrase (e.g., “I work hard”) applies to them with a response option scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses are averaged such that higher scores (from 1 to 5) indicate more of the trait. Coefficient alphas for the O.C.E.A.N. trait elements were: O = .65, C = .83, E = .86, A = .77, N = .85. The reliabilities, means, and standard deviations are shown in Table 3.

Financial Risk Tolerance. Financial risk tolerance was measured with the widely accepted scale developed by Grable and Lytton (1999)—a 13-item self-reported risk assessment comprising three dimensions: (1) investment risk, (2) risk comfort and experience, and (3) speculative risk (however, the authors recommend that the scale not be used at the facet level). The Grable–Lytton scale is a more reliable and valid predictor of financial risk tolerance than other available scales (Grable and Lytton 2003). From past research, the Grable–Lytton scale demonstrates acceptable reliability with coefficient alphas estimated to be roughly .75 (Grable and Lytton 1999). The Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .71 (M = 1.95, SD = .38). Scores were averaged instead of presented as a sum score as is typical for this scale.

Financial Literacy. Financial literacy was measured with the Lusardi and Mitchell (2007) five-question financial literacy index. An example of a question is:

Suppose you had $100 in a savings account and the interest rate was 2 percent per year. After 5 years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow? A) More than 102; B) Exactly 102; or C) Do not Know.

The Lusardi and Mitchell (2007) index was used in this study as it is often used in financial literature and is included in the National Financial Capability Study (FINRA 2021). The NFCS uses five questions with the sixth question as a bonus. Financial literacy is declining, as in 2009, 58 percent of respondents got three or fewer answers correct; in 2012, 61 percent got three or fewer correct; in 2015, 63 percent got three or fewer correct; and in 2018, 66 percent got three or fewer correct (FINRA 2021). For this study, the five-question version of the Lusardi and Mitchell (2007) index was selected and produced an alpha of .62. This sample had a mean of .64 and a standard deviation of .29 (M = .64, SD = .29). Interestingly, despite roughly half of the participants of this sample having undergraduate college degrees—compared to the national average of slightly less than 40 percent (U.S. Census Bureau n.d.)—the average financial literacy score was a failing grade of 64 percent.

Income. A financial performance self-reported measurement of income was collected in the demographics section of the survey. The average income was $45,000 (M = $44,945, SD = $39,198).

Net worth. A self-reported financial performance measurement of net worth was collected in the demographics section of the survey. The average net worth for participants was $115,000 (M = $114,668, SD = $249,512).

Methods

To test the general hypotheses—that personality is a useful predictor of financial outcomes—a series of OLS regressions were run. In addition, bivariate correlations were run to ease interpretation. Additional models accounting for covariates and non-normally distributed data can be found in the supplemental materials. The overall patterns of results do not dramatically change, and given the increased interpretability of the more straightforward models, they are the focus of this manuscript.

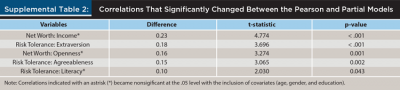

Omnibus regression models including all O.C.E.A.N. characteristics are useful for understanding the predictive ability of overall personality measurement. However, these models are challenging to interpret at the predictor level because of multicollinearity. Instead of reporting the individual beta parameters, which represent only unique variance, we include partial correlations, controlling for the same demographic variables as are included in the omnibus regressions. These partial correlation coefficients directly address the question at hand—how much are individual personality characteristics able to predict financial outcomes?—without conflating these traits with each other.

Assumptions for the OLS regression were addressed through the design of the study (continuous variables, independence of observations), data screening (removal of outliers), and inclusion of bivariate correlations for trait-level interpretation (linearity, heteroscedasticity).

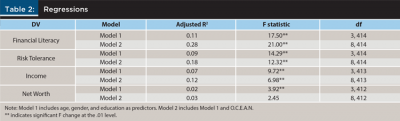

Results

Regression Analysis. We conducted an initial series of regressions to examine the overall incremental prediction of the Big Five traits on our financial outcomes. In all but one of the four regressions, the inclusion of personality metrics significantly improved model fit above and beyond the variance explained by participant age, gender, and educational attainment—in the case of net worth, the overall variance explained is small, so even though adding personality increases the predictive power by 50 percent, it is not a statistically significant increase. Table 2 reports the overall model fit statistics.

Given that the purpose of this paper is to create actionable suggestions for financial professionals interested in considering their clients’ personalities as a part of their practice, we do not focus on the models’ challenging-to-apply (Nimon and Reio 2011) beta weights (though we include these in the supplemental materials). Due to issues of multicollinearity, beta weights—which represent the unique variance in the DV explained by each predictor in the overall model—should not be used to explain the relationships between predictors and the DV (Kraha, Turner, Nimon, Zientek, and Henson 2012; Lynam, Hoyle, and Newman 2006). We instead focus on the correlations between the variables of interest.

Correlation Analysis. Our goal was to examine the simple association between the personality traits and the financial outcomes of interest. This provides the cleanest window into the structure of the data. The simple correlations are reported in Table 3. Additionally, in the interest of understanding the magnitude of the associations between personality and financial outcomes with the variance accounted for by age, gender, and education removed, we conducted a series of partial correlations. Similar to multiple regression, these partial correlations show the association between personality and financial outcomes in a metric that accounts for variance from gender, age, and education. The simple and partial correlations showed similar patterns, with the simple correlations being more stable. Partial correlations are included in the supplemental materials. To account for non-normally distributed financial outcomes (as opposed to transformations), we repeated these analyses using Spearman rank-order correlations; the direction and significance of the pattern of results remained the same. These are also reported in the supplemental materials.

Financial Literacy. Each of the O.C.E.A.N. traits had a significant relationship with financial literacy. Consistent with Hypotheses 1A and 1B, openness (r = .22, p < .01) and conscientiousness (r = .37, p < .01) were positively associated with financial literacy. Hypothesis 1C was also supported as neuroticism (r = –.32, p < .01) was negatively associated with financial literacy. Though not hypothesized, agreeableness (r = .29, p < .01) was also significantly positively associated with financial literacy, and extraversion (r = –.17, p < .01) was significantly negatively correlated with financial literacy.

Financial Risk Tolerance. Four of the five O.C.E.A.N. traits had a significant relationship with financial risk tolerance. Openness (r = –.11, p < .05) had a negative relationship with financial risk tolerance instead of the hypothesized positive relationship; therefore, Hypothesis 2A was not confirmed. Extraversion (r = .43, p < .01) had a significant positive relationship with financial risk tolerance, thus supporting Hypothesis 2B. Conscientiousness (r = –.17, p < .01) and agreeableness (r = –.37, p < .01) had negative relationships with financial risk tolerance, supporting Hypotheses 2C and 2D. However, Hypothesis 2E was not supported as neuroticism (r = –.05, p > .05) was not found to have a significant relationship with financial risk tolerance.

Income. Four of the five O.C.E.A.N. traits had a significant relationship with income. Consistent with Hypotheses 3A and 3B, conscientiousness (r = .17, p < .01) and extraversion (r = .15, p < .01) were significantly positively associated with income. Hypothesis 3C was also supported as neuroticism (r = –.19, p < .01) was significantly negatively associated with income. Though not hypothesized, openness (r = –.12, p < .05) also had a significant negative relationship with income.

Net worth. Three of the five O.C.E.A.N. traits had a significant relationship with net worth. Consistent with Hypothesis 4A, conscientiousness (r = .13, p < .01) was positively associated with net worth. However, Hypothesis 4B was not supported as extraversion (r = .05, p > .05) did not have a significant relationship with net worth. Hypothesis 4C was supported as neuroticism (r = –.13, p < .05) had a significant negative relationship with net worth. Though not hypothesized, openness (r = –.11, p < .05) also had a significant negative relationship with net worth.

Discussion

This study sought to elucidate how the Big Five personality traits may play a role in describing household outcomes related to (1) financial literacy, (2) financial risk tolerance, (3) income, and (4) net worth. Eleven of the 14 hypotheses were supported and 16 of the 20 correlations were significant. OLS regressions and correlations tell a similar story. With regression, these associations are smaller and less stable because age, gender, and education have well-established relationships with aspects of O.C.E.A.N. By controlling for these covariates, we remove meaningful variance attributable to the personality metrics of interest. Acknowledging that these relationships will be weaker as less variance is available to explain, the discussion will focus on the bivariate correlations.

Financial Literacy. It was hypothesized that financial literacy would be positively correlated with openness and conscientiousness and negatively correlated with neuroticism. Each of these hypotheses was supported. When assisting individuals high in C and O, planners may see higher financial aptitudes. Open individuals likely value financial information as a way of continuous learning and have gathered knowledge along their financial journey. Conscientious individuals have likely also gathered financial knowledge possibly through study and determination to master the process. High Os and Cs may benefit from more detailed explanations of advanced topics involving their investing and planning. This advanced learning should allow high Os and Cs to grasp more complex strategies that may assist in reaching their goals. In addition, these individuals will likely appreciate a detailed discussion of the inner workings of various strategies, even if they decide against implementation.

Though neuroticism was negatively correlated with financial literacy, extraversion had a similar negative relationship. When assisting individuals with high E and high N, planners may see lower financial aptitudes. While high Ns may readily admit this shortcoming, high Es may deny low financial literacy as high Es can be prone to overconfidence (Schaefer, Williams, Goodie, and Campbell 2004). Planners assisting high Es and Ns should consider creative ways to spend time on basic financial literacy in review meetings rather than assigning self-learning tasks these individuals may not value or complete.

Financial Risk-Taking. For financial risk-taking, as hypothesized, extraversion had a significant positive relationship with risk tolerance while conscientiousness and agreeableness had significant negative relationships with risk tolerance. In a surprise finding of this sample, openness also had a significant negative relationship with risk-taking. Neuroticism did not have a significant relationship with an individual’s appetite for financial risk-taking. In the current climate, extroverts may pose a unique challenge. When assisting individuals with high E, planners should be mindful that big, extroverted personalities tend to add risk even when it may be detrimental to their long-term goals. Spending extra time evaluating and understanding high Es’ risk tolerance over and above industry protocol should be beneficial with these clients. Extroverts are often concerned with appearance and status (Naumann, Vazire, Rentfrow, and Gosling 2009). High Es may also be at higher risk for “Gambler’s Ruin” (Huygens 1657; Campbell, Goodie, and Foster 2004). A “sandbox strategy” or “trading account” consisting of a small set of risky assets that are fun to discuss at cocktail parties may scratch the risk itch, while not endangering the entire financial plan.

Planners may spend extra time understanding and assisting high Cs and As with their risk tolerance in an attempt to nudge them into riskier assets if needed to accomplish their long-term goals. Planners may consider more detailed explanations of the costs and benefits of risk, appealing to high Cs’ and As’ higher financial literacy.

Income. As hypothesized, income had a positive relationship with conscientiousness and extraversion, and a negative relationship with neuroticism. Financial industry compensation structures incent planning professionals to pursue larger accounts. In search of larger clients with higher incomes, planners may be unknowingly selecting individuals with high C and high E and deselecting individuals with high N. Planners could personally benefit from familiarizing themselves with the unique behavioral patterns of high Cs and high Es and tailoring their communication and recommendations to the individual. For example, knowing a high-income earner is high in conscientiousness should encourage planners to use education and discipline strategies—such as budgeting tools—often appreciated by high Cs. However, high-income Es may not value the extra education and may benefit more from automated strategies that systematically increase discipline—thus lowering risk—such as the automatic enrollment and asset allocation features that are included in various financial tools such as 401(k) plans.

Individuals high in neuroticism face a tall hill to climb. However, planners should be well equipped. Michael Kitces found in his 2018 annual survey of financial advisers that successful advisers often have lower N scores—meaning quality advisers often come with a high dose of emotional stability. With lower incomes, high Ns will need help embracing other paths to wealth building such as financial literacy, discipline, and risk-taking. However, individuals with lower incomes have been shown to have lower financial literacy and less access to financial institutions (Zhan, Anderson, and Scott 2006). High Ns may have the highest need for financial advice without the means to pay. This is an area where financial services might need to consider skills and tools developed in the counseling and mental health fields to better serve high-neuroticism clients. Understanding personality traits may provide clues as to the mechanisms individuals are employing to earn higher incomes that may or may not be beneficial to their long-term goals.

Net Worth. As hypothesized, conscientiousness had a positive relationship with net worth while neuroticism had a significant negative relationship. Extraversion was not found to have a significant relationship with net worth despite the finding that extroverts earn more. These findings, along with other studies (Duckworth et al. 2012), could lead to conscientiousness being considered the “wealth trait.” These industrious individuals—demonstrating a steady, plodding behavior pattern—appear to build higher net worth by using other skills to convert their higher incomes into net worth. Despite also earning higher incomes, high Es did not convert their higher income into higher net worth for this sample. Individuals high in neuroticism had significantly lower net worth, which is not surprising given lower incomes and lower financial literacy.

In total, 11 of the 14 O.C.E.A.N. personality trait hypotheses were supported. In addition, 16 out of a possible 20 personality–financial-outcome relationships were significant, though—as mentioned—a few were unexpected or in the opposite direction of the hypothesis. Clearly, the Big Five personality traits meaningfully predict a range of important household financial outcomes.

Implications

This study has several implications for researchers and those working in the financial services profession. For those in academia and the emerging field of wealth science, this study documents the associations among the Big Five personality traits and four household financial characteristics. Few studies have used net worth as a dependent variable in relation to personality modeling (Duckworth et al. 2012; Nabeshima and Seay 2015). Most personality research related to household finance topics has focused on income as the dependent variable. In The Millionaire Next Door, Stanley and Danko (1996) found that wealthier individuals tend to focus more heavily on measuring their net worth than lower net worth individuals, suggesting conscientiousness. However, few academic studies have followed up on this finding. Hopefully, this study inspires future studies using Big Five and net worth measures. Additionally, results from this study provide support for the model of risk-taking proposed by Irwin (1993).

From an applied standpoint, this study widens the pathway into furthering financial psychological research and expands the tools available to investors and financial service professionals as they attempt to grow wealth. Coaching and education—taking into account their unique O.C.E.A.N. profile—may provide additive benefits over and above standalone financial risk profiles. For example, high Cs may need assistance with adding risky assets to their portfolios, while high Es may need assistance in reducing financial risk and increasing their financial literacy.

Future Research

This study focused on the trait portion of personality. Traits describe a stable pattern of behavior, motivation, emotion, and cognition that can be observed in any sociocultural context (DeYoung 2011). However, individuals possess traits in a package (sometimes referred to as a personality “profile”), not standalone. Exploring repeating patterns of O.C.E.A.N. traits and financial outcomes could prove especially interesting. Secondly, much valuable research in the area of finance and personality is conducted using the University of Michigan’s Health and Retirement Study (e.g., Duckworth et al. 2012; Nabeshima and Seay 2015). Adding a more robust measure of financial risk tolerance and Big Five personality to this survey could potentially open the floodgates for financial personality research. Finally, the McAdams model of personality also includes characteristic adaptations and integrative life stories. Using the McAdams model as a guiding framework, future research that combines traits, experiences, and life stories should provide additional insight into repeatable patterns of financial behavior.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, it is important to replicate this pattern of findings in a larger sample to test their generalization. While the present self-reported MTurk sample had sufficient size to establish stable associations, ideally this study would have used the much larger Health and Retirement Study (HRS) that verifies financial data. Ideally, direct measures of net worth and income based on bank records, spouse reports, or other assessment approaches would be used. However, the purpose of this study was to use a robust measure of personality and risk tolerance not included in the HRS. While MTurk has been validated as a sampling tool, studies have shown that results can differ from the general population (Arditte, Cek, Shaw, and Timpano 2016). To test predictive validity, a larger sample representative of investors, a larger and more refined set of control variables, and multiple indicators of outcome variables would be ideal. Second, this study assessed a single point in time. It would be beneficial to have longitudinal data that establish perhaps a more direct or active role of personality in financial decision-making. For example, changes in conscientiousness at time one may lead to increased net worth at a later time. This would be particularly important to establish over market cycles.

Conclusion

In this study, relationships between aspects of the Big Five model of personality (O.C.E.A.N.) and four standard measures of household financial performance (these being: (1) financial literacy, (2) financial risk tolerance, (3) income, and (4) net worth) were explored using robust measure of personality and financial risk tolerance. Personality traits were found to be significant predictors of meaningful financial variables. Findings from this study suggest that O.C.E.A.N. traits provide unique significant insight into understanding an individual’s financial outcomes. Specifically, participants with high Openness scores reported lower risk tolerance, higher financial literacy, and lower net worth. Those with high Conscientiousness scores reported higher literacy, income, and net worth, along with lower risk tolerance. Participants high in Extraversion had high risk tolerance and income and low financial literacy scores. High Agreeableness was associated with low risk tolerance and high financial literacy. Finally, those with high Neuroticism scores had low scores on all financial variables except for risk tolerance.

This study adds to the body of work by offering a synthesized view of financial outcomes regularly collected by planners through the lens of Big Five personality. While past research has looked at personality and risk tolerance independently, this study is the first to compare these variables using robust measures. From a broad perspective and confirming prior studies (Duckworth et al. 2012; Nabeshima and Seay 2015), conscientiousness appears to be the “wealth trait.” However, by adding risk tolerance to the research, this study found that high Cs do not use higher risk-taking to build their higher wealth. Individuals high in conscientiousness appear to build wealth by being more financially literate and having higher incomes. In addition, this study is the first to examine Nabeshima and Seay’s (2015) call for an “examination” of the relationship between extraversion, financial risk tolerance, and net worth. This research showed that individuals high in extraversion are less financially literate, prefer financial risk-taking, earn higher incomes, but for this sample did not use these outcomes to build significantly higher wealth.

From the standpoint of wealth building, there seems to be more to the story than standalone financial risk tolerance. What does this mean for financial planners and researchers? Specifically, personality characteristics are meaningful predictors of clients’ financial outcomes and deserve serious consideration when conducting research and assisting with financial habit building and real-life outcomes.

References

American Psychological Association (APA). 2017. “Stress in America: The State of Our Nation.” Accessed August 1, 2021. www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2017/state-nation.pdf.

Arditte, Kimberly A., Demet Çek, Ashley M. Shaw, and Kiara R. Timpano. 2016. “The Importance of Assessing Clinical Phenomena in Mechanical TURK RESEARCH.” Psychological Assessment 28 (6): 684–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000217.

Asebedo, Sarah D., Melissa J. Wilmarth, Martin C. Seay, Kristy Archuleta, Gary L. Brase, and Maurice MacDonald. 2019. “Personality and Saving Behavior Among Older Adults.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 53 (2). https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12199.

Baumgartner, Hans. 2002. “Toward a Personology of the Consumer.” Journal of Consumer Research 29 (2): 286–292. https://doi.org/10.1086/341578.

Borghans, Lex, Angela Lee Duckworth, James J. Heckman, and Bas ter Weel. 2008. “The Economics and Psychology of Personality Traits.” Journal of Human Resources 43 (4): 972–1059. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2008.0017.

Bortoli, Daiane de, Newton da Costa, Marco Goulart, and Jéssica Campara. 2019. “Personality Traits and Investor Profile Analysis: A Behavioral Finance Study.” PLoS ONE 14 (3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214062.

Brown, Sarah, and Karl Taylor. 2014. “Household Finances and the ‘Big Five’ Personality Traits.” Journal of Economic Psychology 45 (12): 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2014.10.006.

Campbell, W. Keith, Adam S. Goodie, and Joshua D. Foster. 2004. “Narcissism, Confidence, and Risk Attitude.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 17 (4): 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.475.

Chapman, Benjamin P., and Lewis R. Goldberg. 2017. “Act-Frequency Signatures of the Big Five.” Personality and Individual Differences 116 (10): 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.049.

Costa, Paul T., and Robert R. McCrae. 1992. “Normal Personality Assessment in Clinical Practice: The NEO Personality Inventory.” Psychological Assessment 4 (1): 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037//1040-3590.4.1.5.

DeYoung, Colin G. 2011. “Intelligence and Personality.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Personality, edited by R. J. Sternberg and S. B. Kaufman: 711–37. Cambridge University Press.

DeYoung, Colin G., Lena C. Quilty, and Jordan B. Peterson. 2007. “Between Facets and Domains: 10 Aspects of the Big Five.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93 (5): 880–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.880.

Digman, John M. 1997. “Higher-Order Factors of the Big Five.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73 (6): 1246–1256. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.73.6.1246.

Duckworth, Angela L., David Weir, Eli Tsukayama, and David Kwok. 2012. “Who Does Well in Life? Conscientious Adults Excel in Both Objective and Subjective Success.” Frontiers in Psychology 3 (September). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00356.

Fernandes, Daniel, John G. Lynch, and Richard G. Netemeyer. 2014. “Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Downstream Financial Behaviors.” Management Science 60 (8): 1861–2109. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2013.1849.

FINRA Investor Education Foundation. 2021. Accessed August 1, 2021. www.usfinancialcapability.org/downloads.php.

Gakhar, Divya Verma, and Deepti Prakash. 2017. “Investment Behaviour: A Study of Relationship between Investor Biases and Myers Briggs Type Indicator Personality.” Opus: HR Journal 8 (1): 32–60.

Goldberg, Lewis R. 1993. “The Structure of Phenotypic Personality Traits.” American Psychologist 48 (1): 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26.

Goldberg, Lewis R. 1999. “A Broad-Bandwidth, Public Domain, Personality Inventory Measuring the Lower-Level Facets of Several Five-Factor Models.” Personality Psychology in Europe 7 (1): 7–28.

Goodman, Joseph K., Cynthia E. Cryder, and Amar Cheema. 2013. “Data Collection in a Flat World: The Strengths and Weaknesses of Mechanical Turk Samples.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 26 (3): 231–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1753.

Grable, John E. 2000. “Financial Risk Tolerance and Additional Factors That Affect Risk Taking in Everyday Money Matters.” Journal of Business and Psychology 14 (June): 625–630. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022994314982.

Grable, John E., and Ruth Lytton. 1999. “Financial Risk Tolerance Revisited: The Development of a Risk Assessment Instrument*.” Financial Services Review 8 (3): 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1057-0810(99)00041-4.

Grable, John E., and Ruth Lytton. 2003. “The Development of a Risk Assessment Instrument: A Follow-Up Study.” Financial Services Review 12 (3): 257–274.

Grable, John E., Ruth Lytton, and Barbara O’Neill. 2004. “Projection Bias and Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Behavioral Finance 5 (3): 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427579jpfm0503_2.

Grable, John E., and So Hyun Joo. 2004. “Environmental and Biopsychosocial Factors Associated with Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 15 (1).

Haslam, N., E. Holland, and P. Kuppens. 2012. “Categories Versus Dimensions in Personality and Psychopathology: A Quantitative Review of Taxometric Research.” Psychological Medicine 42 (5): 903–920. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711001966.

Heineck, Guido. 2011. “Does it Pay to Be Nice? Personality and Earnings in the United Kingdom.” ILR Review 64 (5): 1020–1038.

Hoffmann, Arvid O., and Leonora Risse. 2020. “Do Good Things Come in Pairs? How Personality Traits Help Explain Individuals’ Simultaneous Pursuit of a Healthy Lifestyle and Financially Responsible Behavior.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 54 (3): 1082–1120. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12317.

Huygens, Christiaan. 1657. De Ratiociniis in Ludo Aleae. Lugd. Batav.

Investor.gov. n.d. “Assessing Your Risk Tolerance.” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Accessed August 1, 2021. www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/getting-started/assessing-your-risk-tolerance.

Irwin, C. E. 1993. “Adolescence and Risk Taking: How Are They Related?” In Adolescent Risk Taking: 7–28. Sage Publications, Inc.

John, Oliver P., and Sanjay Srivastava. 1999. “The Big Five Trait Taxonomy: History, Measurement, and Theoretical Perspectives.” In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, edited by L. A. Pervin & O. P. John: 102–138. New York: Guilford Press.

Judge, Timothy A., Chad A. Higgins, Carl J. Thoresen, and Murray R. Barrick. 1999. “The Big Five Personality Traits, General Mental Ability, and Career Success across the Life Span.” Personnel Psychology 52 (3): 621–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00174.x.

Judge, Timothy A., Jessica B. Rodell, Ryan L. Klinger, Lauren S. Simon, and Eean R. Crawford. 2013. “Hierarchical Representations of the Five-Factor Model of Personality in Predicting Job Performance: Integrating Three Organizing Frameworks with Two Theoretical Perspectives.” Journal of Applied Psychology 98 (6): 875–925. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033901.

Killins, Robert. 2017. “The Financial Literacy of Generation Y and the Influence That Personality Traits Have on Financial Knowledge: Evidence from Canada.” Financial Services Review 26 (2): 143–165.

Kitces, Michael, and Meghaan Lurtz. 2018, November 12. “The Defining Personality Traits of (Successful) Financial Planners.” Nerd’s Eye View. www.kitces.com/blog/the-defining-personality-traits-of-successful-financial-planners/.

Kraha, Amanda, Heather Turner, Kim Nimon, Linda Reichwein Zientek, and Robin K. Henson. 2012. “Tools to Support Interpreting Multiple Regression in the Face of Multicollinearity.” Frontiers in Psychology 14 (3).

Lauriola, Marco, Angelo Panno, Irwin P. Levin, and Carl W. Lejuez. 2014. “Individual Differences in Risky Decision Making: A Meta-Analysis of Sensation Seeking and Impulsivity with the Balloon Analogue Risk Task.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 27 (1): 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1784.

Letkiewicz, Jodi C., and Jonathan J. Fox. 2014. “Conscientiousness, Financial Literacy, and Asset Accumulation of Young Adults.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 48 (2): 274–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12040.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2007. “Baby Boomer Retirement Security: The Roles of Planning, Financial Literacy, and Housing Wealth.” Journal of Monetary Economics 54 (1): 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2006.12.001.

Lynam, Donald R., Rick H. Hoyle, and Joseph P. Newman. 2006. “The Perils of Partialling: Cautionary Tales from Aggression and Psychopathy.” Assessment 13 (3): 328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191106290562.

Maczulskij, Terhi, and Jutta Viinikainen. 2018. “Is Personality Related to Permanent Earnings? Evidence Using a Twin Design.” Journal of Economic Psychology 64 (2): 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2018.01.001.

Maples-Keller, Jessica L., Rachel L. Williamson, Chelsea E. Sleep, Nathan T. Carter, W. Keith Campbell, and Joshua D. Miller. 2017. “Using Item Response Theory to Develop A 60-Item Representation of the Neo Pi–r Using the International Personality Item POOL: Development of THE IPIP–NEO–60.” Journal of Personality Assessment 101 (1): 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2017.1381968.

Mayfield, Cliff, Grady Perdue, and Kevin Wooten. 2008. “Investment Management and Personality Type.” Financial Services Review 17 (3).

McAdams, Dan P., and Jennifer L. Pals. 2006. “A New Big Five: Fundamental Principles for an Integrative Science of Personality.” American Psychologist 61 (3): 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.61.3.204.

Mendelsohn, Gerald. 1993. “It’s Time to Put Theories of Personality in Their Place, or, Allport and Stagner Got It Right, Why Can’t We?” In Fifty Years of Personality Psychology, edited by Kenneth H. Craik, Robert Hogan, and Raymond N. Wolfe: 103–115. Boston: Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2311-0.

Nabeshima, George, and Martin Seay. 2015. “Wealth and Personality: Can Personality Traits Make Your Client Rich?” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (7): 50–57.

Nandi, Alita, and Cheti Nicoletti. 2014. “Explaining Personality Pay Gaps in the UK.” Applied Economics 46 (26): 3131–3150. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2014.922670.

Naumann, Laura P., Simine Vazire, Peter J. Rentfrow, and Samuel D. Gosling. 2009. “Personality Judgments Based on Physical Appearance.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 35 (12): 1661–1671. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209346309.

Nicholson, Nigel, Emma Soane, Mark Fenton-O’Creevy, and Paul Willman. 2005. “Personality and Domain-Specific Risk Taking.” Journal of Risk Research 8 (2): 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1366987032000123856.

Nimon, Kim, and Thomas G. Reio. 2011. “Regression Commonality Analysis: A Technique for Quantitative Theory Building.” Human Resource Development Review 10 (3): 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484311411077.

Paolacci, Gabriele, and Jesse Chandler. 2014. “Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a Participant Pool.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 23 (3): 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414531598.

Pinjisakikool, Teerapong. 2018. “The Influence of Personality Traits on Households’ Financial Risk Tolerance and Financial Behaviour.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics 30 (1): 32–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0260107917731034.

Prevoo, Tyas, and Bas ter Weel. 2015. “The Importance of Early Conscientiousness for Socio-Economic Outcomes: Evidence from the British Cohort Study.” Oxford Economic Papers 67 (4): 918–948. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpv022.

Schaefer, Peter S., Cristina C. Williams, Adam S. Goodie, and W. Keith Campbell. 2004. “Overconfidence and the Big Five.” Journal of Research in Personality 38 (5): 473–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2003.09.010.

Seidor, Lane. 2018. “Personality, Motivation, and Financial Risk Tolerance.” Athens, GA.

Stanley, Thomas J., and William D. Danko. 1996. The Millionaire Next Door. Athens, GA: Longstreet Press.

Thaler, Richard H., and Eric J. Johnson. 1990. “Gambling with the House Money and Trying to Break Even: The Effects of Prior Outcomes on Risky Choice.” Management Science 36 (6): 643–766. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.36.6.643.

Thanki, Heena, Anil Kumar Goyal, and S. O. Junare. 2020. “Personality Traits, Financial Risk Attitude, and Long-Term Investment Intentions: Study Examining Moderating Effect of Gender.” Finance India 34 (2): 785–798.

Thanki, Heena, Anushree Karani, and Anil Kumar Goyal. 2020. “Psychological Antecedents of Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Wealth Management 23 (2): 36–51. https://doi.org/10.3905/JWM.2020.1.111.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. n.d. “Latest Benefits News Release.” Accessed August 1, 2021. www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/.

U.S. Census Bureau. n.d. “United States Census Quick Facts.” Accessed February 26, 2021. www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/IPE120219.

U.S. Department of Labor (DOL). n.d. “Conflict of Interest Final Rule.” Accessed August 1, 2021. www.dol.gov/agencies/ebsa/laws-and-regulations/rules-and-regulations/completed-rulemaking/1210-AB32-2.

Zhan, Min, Steven G. Anderson, and Jeff Scott. 2006. “Financial Management Knowledge of the Low-Income Population: Characteristics and Needs.” Journal of Social Service Research 33 (1): 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1300/J079v33n01_09.

Appendix: