Journal of Financial Planning: September 2014

Jamie P. Hopkins, J.D., RICP®, is an associate professor of taxation at The American College and the associate director of the New York Life Center for Retirement Income. Email author HERE.

Ilya Lipin, J.D., LL.M., is an attorney in Philadelphia. He received his LL.M. in trial advocacy from Temple University School of Law, an LL.M. in taxation from Villanova School of Law, and J.D. from Thomas M. Cooley Law School. Email author HERE.

John Whitham is the director of digital resources at The American College of Financial Services. He holds dual Master of Science degrees in information science and information systems from Drexel University. Email author HERE.

Executive Summary

- The digitization of business assets has created a new challenge for the development of succession plans for small business owners. Without a well-defined and managed succession plan that considers digital assets, these valuable business intangibles may perish resulting in irreversible damage.

- This paper defines digital assets, identifies types of digital assets used by small business owners, and expands upon traditional challenges faced by small business owners who must now account for digital assets in succession planning.

- Guidance is provided on how to create a successful digital asset succession plan for a small business with current legal mechanisms and best business practices.

Financial planners work with a variety of clients, each with their own unique goals, characteristics, and needs. The solutions generated for these clients must be tailored to the individual’s unique circumstances. Plans should evolve as these circumstances change.

The digitization of business assets has created a need for small business owners to have a well-defined and well-managed digital asset succession plan in place. Traditionally, small business owners struggle with proper succession planning. Digital assets present an entirely new challenge when developing a succession plan. As such, financial planners working with small business owners need to be aware of the challenges of developing a digital asset succession plan. Planners must be abreast of the current vehicles for digital asset management.

This paper defines digital assets and identifies the types of digital assets small business owners will most likely rely upon. It examines the traditional challenges small business owners face with succession planning and discusses specific challenges associated with creating a digital succession plan for a small business owner. Best practices for digital asset management during the lifetime of the business owner are also discussed, with a focus on how these practices can better prepare the small business owner to create a successful digital asset succession plan. Finally, the paper provides guidance on how to create a successful digital asset succession plan for a small business with current legal mechanisms and best business practices.

It must not be forgotten that financial planners play a crucial role in preparing clients for financial uncertainties, such as dealing with the management, protection, and transfer of digital assets. By the end of this review, a financial planner should understand the importance of being able to explain to small business owners the importance of digital asset ownership rights, location, accessibility, and transferability. Additionally, the financial planner should not forget the valuable role that an estate planning attorney can play in developing a plan for the disposition of a small business owner’s digital assets. With the legal atmosphere in flux surrounding digital asset ownership rights, a lawyer should be consulted when dealing with any complex problems and to ensure that the digital asset plan works in conjunction with any other existing estate or succession plans.

Why Do Digital Assets Matter?

Financial planners and their clients live in a digital world. Businesses are expected to have an online presence. As a result, assets are being digitized. This has the effect of transforming many traditional, physical assets into electronically stored content referred to as “digital assets.” Digital assets include items stored electronically in binary code on digital storage devices, such as computers, hard drives, and cellular phones. Digital assets do not, however, include the computers, hard drives, cellular phones, or digital storage devices themselves.

Small businesses rely on a wide range of digital assets. These assets impact business processes, marketing, research and development, and sales. In some cases, a company’s business model might revolve entirely around digital assets.1 Small software companies, for example, may consider their entire product line a digital asset. However, most small businesses rely on a mix of physical and digital assets, where digital assets can include a website, email, software, consumer information, payroll systems, ordering systems, online banking, photographs, and accounting information.

Roughly 99 percent of all U.S. employers are small businesses, defined as companies with less than 500 employees, according to the U.S. Small Business Administration. However, because a business is “small” does not mean a financial planner should ignore the business. Small businesses can mean big business, as they employ a total of more than 120 million people and generate $989 billion in revenue per year, according to 2008 U.S. Census data.

Financial planners are the perfect group to begin the digital asset succession planning discussion with small business owners, because many of those business owners may not consider themselves financially savvy. Small business owners often need outside advice on a variety of topics, including retirement readiness, payroll processes, and budgetary efficiency. Small business owners also often contact financial planners about succession planning, creating an opportunity for the planner to tackle the unique challenges of digital asset succession planning.

With more small businesses involved in online business activities,2 the challenges of digital asset succession planning are not only unique, they are ever-changing. For example, roughly 42 percent of small business owners consider marketing through social media to be an effective strategy, according to Bank of America’s 2012 Small Business Owner Report. Social media accounts, and the content within them, qualify as digital assets, but their value and usability will require unique consideration when passed down from incumbent to successor.

Methods of online marketing and trends in social media can change very quickly. It is not enough to simply exchange a password in a succession plan. Although 97 percent of small businesses rank “keeping up with technology” as either “very important” or “somewhat important,” many small businesses may not know the best practices necessary to improve their firm’s relationship with technology, according to the National Small Business Association’s (NSBA) 2013 small business technology survey. This provides financial planners with an important added value proposition in discussing digital assets and digital asset succession planning.

The 2013 NSBA tech survey also found that 87 percent of small businesses use a desktop computer, 84 percent use a laptop, 74 percent use a smart phone, and 41 percent use a tablet, and that roughly 40 percent of small business owners handle their own IT and another 32 percent is handled by a single employee. As a result, a small business’s digital assets may be managed by one person or just a few people without specific training or experience with digital asset management or succession planning.

Common Succession Planning Problems for Small Businesses

Digital assets are crucial for the proper functioning of a small business, yet many small business owners have no digital succession plan or strategy to dispose of these assets in the event of their death. With roughly 28 million small businesses in the United States, and a business death rate of 80 percent, nearly 224,000 small business owners could die each year, according to 2010 data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. However, many people are not aware of how important digital assets are to their company’s day-to-day operation. According to 2012 research conducted by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants’ Succession Planning Resource Center, only 6 percent of sole proprietors have a written succession plan in place. Businesses with no written plan rely instead on informal training and tacit knowledge transfer, often resulting in a major loss of strategic and operational knowledge during succession (Bracci and Vagnoni 2011).

Consider the following hypothetical situation to illustrate how important digital assets are to the proper functioning of a small business. Mr. Smith is a third generation owner of a custom glass producer. His company does roughly $5 million of business a year with a net profit of roughly $500,000 a year. He has five employees, including his two sons. All employees work in the warehouse creating custom glass. As the owner, Mr. Smith manages the company’s finances, payroll, accounting, customer orders, delivery, and banking through a variety of online service providers. He uses one system to set up the firm’s payroll. All customer orders are placed through the firm’s website, which keeps track of the orders, deliveries, and payments. Mr. Smith is the only person in the company who knows how to access these electronic services, and upon his premature and sudden death, the company would be left without a practical way to access customer orders, payroll, or accounting. While Mr. Smith’s sons feel they could eventually gain access to this information, the lack of any digital asset succession plan would delay customer orders for months, causing hundreds of thousands of dollars of loss.

Financial loss is not the only concern for small businesses planning for digital asset succession. Knowledge loss is a major concern, because, like Mr. Smith, the proprietor is often the central source of competencies and capabilities across the organization (Bracci and Vagnoni 2011). Few, if any, in a firm possess the depth of knowledge embedded in the proprietor’s mind. So much of this knowledge is tacit that even those with written plans will be challenged to transfer the necessary information. Written plans can relay explicit knowledge about assets, property, and legal procedures. Plans can also speak to strategic planning and the intended application of resources. Plans are less likely, however, to capture information about the culture of the organization, the historical trajectory of its competitiveness, or the complexities of its daily operations.

The challenge of knowledge transfer is not an impossible barrier to overcome. However, it is one of the most relevant obstacles in the transfer of a small business from incumbent to successor (Malinen 2004). The problem is the degree to which an organization is dependent on a single individual (Feltham, Feltham, and Barnett 2005) and the ability to formalize that individual’s knowledge and skills through routines or technological support (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995). Organizations with a high degree of dependence on a single manager are particularly at risk as other work and time demands make it difficult for the manager to spend time with new successors or document information (Ip and Jacobs 2006).

Most small businesses lack any formal human resource development infrastructure, leaving organizational development, career development, and the learning and development of potential successors up to the proprietor (Sambrook 2005). Considering the proprietor’s generalist position within the organization, it is unsurprising that the owner should lack any specialized training in these areas. In fact, among the most common reasons for succession failure in small businesses are: (1) the failure to develop appropriate training and personnel initiatives; (2) the limited number of suitable employees to take over responsibilities; and (3) interference of company politics (Ip and Jacobs 2006). Assuming the business owner does possess the necessary human resource skills, his or her vulnerability to succession failure increases the longer he or she waits to identify and develop an appropriate successor. Ip and Jacobs (2006) found that men in their late 50s and older are the most susceptible to succession failure due to lack of long-term planning and preparedness.

Current Challenges

In order to plan for the management, disposition, and succession of digital assets, financial planners must understand the logistical, business, and legal concerns facing digital succession planning.3 Small businesses rely upon digital assets on a daily basis, but many proprietors overlook their complexity, especially with regard to succession planning. It is important for professional advisers to have an understanding of the issues that could arise with regards to digital assets in order to properly advise their clients.

Logistical challenges to digital assets. Digital assets, unlike traditional physical business assets, are often difficult to locate and access. This is the case mainly because digital assets are often stored with a third-party online service provider rather than with the asset’s owner or the small business. For example, emails are generally stored with the email provider (Google, AOL, Yahoo!, Microsoft, etc.), which can create a series of logistical concerns for the small business owner. As many small business digital assets are only managed by the owner, the location of these assets and their very existence might be a mystery to anyone other than the small business owner. As such, in the event of the owner’s death, few in the company might be aware of the location of digital assets, which could result in a permanent loss of institutional knowledge.

Another concern is the accessibility of digital assets. Digital assets are often held by online service providers and stored in a password-protected individualized account. To access the account, you need to know where the asset is located and have the password and username. Without this information, accessing digital assets can become extremely difficult, even if you have the legal right and ownership of the digital assets.

For example, if the small business owner leaves a list of digital assets and service providers to his successor, but fails to provide passwords and usernames, it is like having a locked safe without the combination. In many cases, the service providers will not disclose the username and password to anyone but the original owner, limiting the ability of the business to access these digital assets upon the death of the business owner.

Additionally, many small business owners do not feel comfortable disclosing their passwords, usernames, and digital asset locations to just any employee. They often keep these secret to protect their privacy, the privacy of their customers, and to keep their company assets safe. Furthermore, passwords and digital asset access information might change daily, weekly, or monthly. It can be difficult to keep track of access information. Serious and real concerns must be managed when discussing the privacy and security of digital assets. Small business owners often rely on their own efforts to manage and primarily protect access to these digital assets. This secrecy, for legitimate reasons, coupled with the vast number of passwords, usernames, and online service providers can hamper the ability of institutional knowledge to be passed along upon the owner’s death.

Legal issues facing digital asset transferability. A variety of legal issues can frustrate the proper estate and succession planning of digital assets. These legal issues primarily deal with the ability to transfer digital assets because of accessibility and ownership issues, and the inability of traditional estate planning tools to successfully and safely handle the disposition of digital assets.

The disposition and maintenance of digital assets is paramount to digital asset succession planning for small businesses. While digital assets represent a property right that allows the owner to manage, transfer, and dispose of them, the actual owner of the digital asset might not always be the small business owner. The small business owner might only have a lifetime lease to use the digital asset or the digital service. Therfore, when the small business owner dies, the small business itself may have no claim to the digital asset. This is a potentiality of great concern and should be dealt with through the small business’s digital asset management system. A proper digital asset management system can help determine the ownership rights, location, and accessibility of these assets.

Although the small business owner might not own the actual digital asset, he or she might retain some other type of ownership right through a contractual agreement with the service provider or under copyright laws. Consider email ownership. In some cases people might not own the email itself, but they still have a copyright in the written material in the email, so the service provider could restrict access to the email but could not use the information in the email because the author owns the property.

Additionally, the ability to transfer, bequest, dispose of, or distribute a digital asset might be limited by the digital service provider agreement. These agreements are contracts. Contracts control the rights and obligations of the online service provider and consumer. For example, under the Yahoo!® service provider agreement, a user’s content is non-transferable and will be deleted upon the user’s death.4 As such, it is important that the small business owner set up any Yahoo! accounts under the name of the business and not their own name. The small business owner needs to examine the ownership rights and ability to transfer the digital assets in light of the agreed upon online service provider agreement.

Despite the many legal, logistical, and business issues regarding digital asset succession planning for small businesses, the majority of these issues can be dealt with through proper planning and digital asset management systems. However, in order to plan for these issues, the small business owner needs to be advised about monitoring concerns. The financial planning professional should explain to the small business owner the need to understand the ownership rights of his or her digital assets, the location, the accessibility information, and the transferability rights.

The Importance of a Digital Asset Management System

At their most basic, digital asset management (DAM) systems consist of computer software and hardware used for storing digital assets. The size of a company and its stock of digital assets will determine the complexity of a system. Systems can be small and dedicated to the management of one type of digital asset, or they can be very large, consisting of several collections of multiple asset types or even multiple DAM systems. Big companies invest a lot of money in DAM-specific software, while small businesses normally do not want or need such expensive, complex solutions.

Large DAM systems are not essential for effective management of digital assets for small businesses. However, to make up for the features and functions of such systems, small business personnel need to standardize the tasks and decisions surrounding the management of their digital assets. A small marketing firm, for example, may have a large collection of digital picture files. These files consist of headshots, stock photographs, company logos, and other images they have created for publications and press releases for their various clients. The firm’s graphic designer stores all of her files on her computer’s desktop; the photographer manages his files using Flickr; and the art director stores everything she approves in a folder on the firm’s public server. Assuming each person has his or her own “system” for locating and retrieving the files, then each person is effectively managing their own files. As assets of the firm, however, these files need to be accessible to any employee, especially these workers’ successors.

Combined with appropriate software and hardware, effective DAM systems require standardized practices surrounding the ingestion, annotation, cataloging, storage, retrieval, and distribution of digital assets. All the systems in the scenario above fulfill the necessary functions of a DAM system. The graphic designer, for example, uses her desktop’s folder system to ingest her files from the program in which they were made. She does this simply by saving the file from a photo editing application to the folder. Once the file is saved to the folder, it is stored there until manually deleted. Assuming the designer gives her files identifiable titles, these titles act as an annotation of the file, as well as the name by which the folder system catalogs the file. When the designer is ready to retrieve and distribute the file, she can find it once more by its title and then attach it to an email. This system of storing and accessing files is a basic example of an individual effectively managing digital resources. It is not an example of a company effectively managing its digital assets because the company is not aware of the system.

Depending on the size of a company, its stock of digital assets, and the value of those digital assets, the standards surrounding DAM can be more or less strict. Generally, any company managing confidential client information will want to enforce strict standards for storing and labeling this information. Putting issues of security aside, clients would put very little trust in a successor who cannot locate their files or previous transactions with a client. Likewise, loss of assets that help the company to serve clients can quickly threaten that company’s success. Lost passwords to bank accounts or ordering systems can cause delays in service. Missing webmaster credentials for web pages or applications can also drive clients to other businesses.

A Digital Asset Succession Plan for Small Businesses

Currently, digital asset succession planning is accomplished through the use of wills, trusts, and online digital estate planning services, or any combination of these three general options. When consulting an owner of a small business regarding digital asset succession, financial planners should consider all three of these options. Financial planners should also recommend the services of an attorney and data management provider.

Wills. Wills are a commonly used mechanism that allow for legal expression of an individual’s desires regarding the transfer and disposition of their assets after death. In digital asset succession planning for small business owners, wills can provide valuable guidance regarding access, transfer, disposition, and maintenance of digital assets following the owner’s death. Wills can also be used to give affirmative notice to heirs that the small business owner would like for the business to be discontinued after his or her death and to engage in winding up procedures. Attorneys providing estate planning services generally inquire into their client’s digital assets. Attorneys also seek their client’s direction as to the preservation or disposition of digital assets (Colloway 2013). For the purposes of digital estate planning for small business owners, wills should generally address the following matters: (1) creation of a digital estate succession plan; (2) formation of digital asset inventory and identification of its location; (3) appointment of an executor; and (4) consent for accessing the deceased’s digital assets.

Through a will, a small business owner can appoint a successor to the business, as well as contingent successor(s), in the event the original successor is unavailable to assume the position. Identifying successors provides for both short- and long-term certainty that the small business operations are going to continue and give necessary assurance to its suppliers, business partners, and customers. Similarly, through a will, a small business owner can notify his or her desire for the business to be wound up after death. This is typically accomplished by listing specific shutdown procedures and instructions for the disposition of assets.

During the will drafting process, a small business owner should create a list all of digital assets owned, their locations, points of access, and consider methods of their transferability (Smith 2012). It is important to collect all of the information associated with each account, such as the username, password, answers to secret questions, and other identifying access-granting factors. Going through all of the relevant data will allow the small business owner to confirm everything he or she desires to convey to heirs and third parties.

Wills should appoint a special digital executor. This is a person who specializes in the distribution and management of a deceased’s digital assets (Armstrong 2012). In case heirs of the deceased choose to discontinue running the small business, the digital executor could be responsible for terminating email, social media, online shopping, and/or any business banking accounts (Korzec and McKittrick 2011).5 The digital executor might also be required to notify customers about the passing of the small business owner, the heirs’ decision not to continue the business, and wind down any existing affairs. Similarly, if the heirs decide to continue operation of the small business, the digital executor’s role would be to obtain and transfer all of the necessary account and password information and to assist with the transition of the operations.

Wills should provide for necessary permission to the executor to access the deceased’s tangible property such as computers, hard drives, and other memory storing devices, as well as access to online accounts including email, cloud storage, and the like to avoid potential violation of federal and state laws (Korzec and McKittrick 2011).

The inability of heirs or a special digital executor to access the deceased’s digital accounts can be costly. For instance, without access to key accounts, heirs may not have the ability to pay vendors, utility, and financial providers in a timely manner. Heirs may not be able to collect accounts receivables or ship purchased items, which could affect the reputation of the business and its financial viability (Sharp 2013). From a compliance perspective, the inability to access digital assets may affect timely tax and other regulatory filings, which may subject the business to penalties and interest. Lastly, heirs may have to hire an attorney to obtain a court order compelling access to the accounts and a computer forensic expert to obtain access to data stored on computers and various electronic devices (Karas 2012).

For small business owners, using wills as the only method for digital estate planning can be problematic due to privacy concerns, rapid growth or turnover of the digital assets, and uncertainty of whether service providers will respect wills as means of transferring ownership of digital assets. First, as wills become public during the administration period, wills can reveal or provide access to the business’s and its deceased owner’s valuable private information (Carroll, Romano, and Carter 2011). Accordingly, wills should avoid providing account names, passwords, and similar data, as this information can be used by competitors or other individuals. Second, small business digital assets may experience rapid growth or have a high turnover rate. This may lead to certain provisions of the will regarding digital assets becoming outdated. Such prompt change in digital assets may require impractical solutions, such as updating the will on a daily basis, or assuming the risk that the will’s provisions may not be valid (Beyer and Cahn 2012). Lastly, because user and online service provider relationships are guided by contract law, it “is unclear whether service providers will respect the terms of wills to transfer ownership of digital assets” (Beyer and Cahn 2012). For instance, where the digital assets take the form of a non-transferable license, such as a privilege to use email services, privilege to use the license will often expire after the licensee’s death.

Trusts. Using trusts, rather than relying solely on wills, can provide for more desirable results for small business owners attempting to transfer their digital assets to heirs and third parties. A trust is a property interest held by a trustee at the request of another person called the settlor, for the benefit of a third-party beneficiary.6 A trust holding digital assets should generally be managed as a traditional trust, where a trustee, at the request of another, manages the digital assets for the trust beneficiaries. Unlike wills, trusts can provide for additional privacy protection, ease of transferability due to potential existing licensing agreements between the deceased and the service provider, and simplicity of updates and modification (Hopkins 2013).

First, holding digital assets in trusts keeps sensitive information about the decedent’s digital assets private. This feature keeps a small business owner’s usernames, passwords, Social Security numbers, financial documents, trade secrets, and other valuable intangible information away from the public eye.

Second, the decedent does not always have the exclusive right to the ownership of digital assets contained within realms of a third-party provider’s website. For instance, while a profile and its contents on a social networking website may belong to the decedent, the third-party provider generally has the exclusive rights to its management, and as such, the third party may define rules pertaining to accessibility and transferability. Service providers may treat access to an individual account by a third party as a violation of their license agreement, which may lead to termination of an account and loss of digital assets (Cahn 2011). However, when licenses and underlying digital assets are transferred via trust, the trustee has the legal authority to manage these assets in accordance with the client’s instructions.

Lastly, trusts can be amended more easily than wills. Small business owners can remain in control over the digital assets that they transfer into the trust and keep relevant information associated with the transferred property current (Cahn 2011). Such self-management and maintenance of digital assets within the trust should allow for cost savings.

Online digital estate planning services. DAM vendors can provide valuable service to small businesses that minimally rely on technology or are very technology driven. Using a DAM vendor allows a small business owner to select digital assets and preserve them for future use by others, assure management and updates associated with digital assets, and select persons who will have rights of access to the digital assets.

Specifically, DAM services can store business content such as images, graphics, and videos (Meserve 2003). DAM services can be used to centralize the location for DAM providers and also store the user’s previously copied and downloaded data from sources that have service provider agreements that may limit heirs’ ability to access digital assets.7

Digital estate plans should consider provisions for periodic maintenance to ensure that the small business’s latest data has been properly saved and included in the estate plan. Passwords, usernames, and other identifying data may need to be updated for accuracy and security purposes. Small business owners can limit access to information held by DAM vendors only to specific individuals. For instance, access to DAM data can be granted only to persons previously named in a will, such as a special digital executor, who must provide a death certificate and notarized letter confirming the small business owner’s death (Null 2013).

However, there are a few caveats associated with the use of DAM vendors. Small business owners, as well as financial planners, should be wary of which DAM vendor to use for preservation and management of digital assets. Employment of a lesser-known or trusted vendor can lead to significant exposure of private information, which can lead to identity theft. DAMs should not be used alone, but in conjunction with estate planning documents tailored to the needs of the small business owner. As protectors of privacy, DAM vendors should employ security techniques to verify that only authorized individuals obtain access to the deceased’s digital assets (Walker and Blachly 2011). Further, without testamentary documents guiding methods of disposition, using a DAM to hold digital assets in their possession is not equivalent to a legal transfer.

The Future of Digital Asset Planning for Small Businesses

Currently, there is no uniform law that governs a fiduciary’s right to access and manage a deceased business owner’s digital assets. As of early 2014, there is no federal law addressing this issue. Only Connecticut, Idaho, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island have enacted legislation providing for an executor’s rights to access the deceased’s email, social media, and networking accounts.8 However, continuing growth of technology and narrow application “render these state statutes relatively unhelpful for the majority of digital assets within decedents’ estates” (Ray 2013).

The Uniform Law Commission, a nonpartisan organization that drafts uniform modern laws that individual states often consider for guidance in promulgation of their legislation, has issued a draft version of legislation called the Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act. This draft legislation aims to provide guidance regarding personal representatives of the decedents’ estate, conservators for protected persons, and agents acting pursuant to a power of attorney. The draft legislation also provides rules that allow trustees access to a deceased business owner’s digital assets and accounts.9

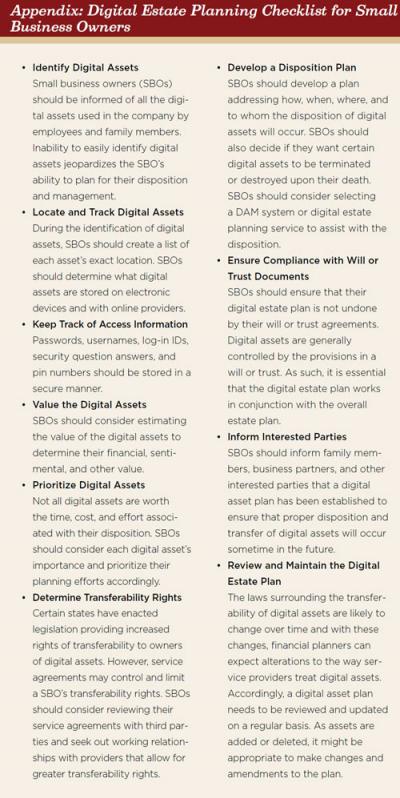

Until attorneys, accountants, and financial planners have further concrete guidance from either federal or state authorities in this rapidly developing area of law, small business owners are encouraged to work with their advisers to prepare adequate succession plans that will allow for their fiduciaries to access, manage, preserve, and dispose of their digital assets. Financial planners should discuss digital estate planning with their clients to ensure proper management of assets. A checklist, such as the one provided in the Appendix, can be used to help a financial planner prepare his or her clients for the proper disposition of digital assets. Ultimately, making sure clients are aware of these assets, the planning choices available, and setting forth a plan of action are crucial to ensuring substantial value is not lost during the transition or disposition of the small business owner’s company.

Endnotes

- Companies like Google and Facebook have incredibly expensive software and digital assets.

- According to the National Small Business Association, in 2013: 85 percent of small businesses purchased supplies online, 83 percent managed bank accounts online, 72 percent paid bills online, 44 percent managed payroll online, 59 percent held conferences online, and 45 percent conducted meetings online. About 57 percent of small businesses reported using cloud-based computing technologies in their business. Roughly 82 percent of small businesses had a traditional website, 18 percent had a mobile website, and 5 percent had a digital application for their business. Lastly, around 28 percent of small businesses sold products and services online, 85 percent of which were sold directly through their own website. Many of the digital assets associated with these activities were handled by the small business owner, with 27 percent of small business owners managing their own website.

- When an individual plans for the disposition of their digital assets upon their death this is often referred to as digital estate planning. However, with a small business, this is referred to a digital succession plan.

- See Yahoo!® Terms of Service: info.yahoo.com/legal/us/yahoo/utos/utos-173.html.

- Korzec and McKittrick (2011) noted that “[i]f the executor accesses a decedent’s email account without the email provider’s knowledge, that action might violate the email provider’s terms of service. Such access could constitute identity fraud or violate a cybercrime law such as the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.”

- Black’s Law Dictionary (9th ed. 2009).

- See Sharp (2013).

- Connecticut SB 262 Public Act No. 05-136 (Oct. 1, 2005); Idaho SB 1044 (Jul. 1, 2011); Oklahoma HB 2800 (Nov. 1, 2010); Rhode Island - Title 33: Probate practice and procedure, Chapter 33-27: Access to Decedents’ Electronic Mail Accounts Act, Section 33-27-3 (May 1, 2007).

- See the Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (Draft), National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws: uniformlaws.org/Committee.aspx?title=Fiduciary+Access+to+Digital+Assets.

References

Armstrong, Alexandra. 2012. “Estate Planning in a Digital World.” Better Investing 62 (4): 11–12.

Beyer, Gerry, and Naomi Cahn. 2012. “When You Pass on, Don’t Leave the Passwords Behind: Planning for Digital Assets.” Probate and Property 26 (1): 40–43.

Bracci, Enrico, and Emidia Vagnoni. 2011. “Understanding Small Family Business Succession in a Knowledge Management Perspective.” The IUP Journal of Knowledge Management 9 (1): 7–36.

Cahn, Naomi. 2011. “Postmortem Life Online.” Probate and Property 25 (4): 36–39.

Carroll, Evan, John Romano, and Jean Carter. 2011. “Helping Clients Reach Their Great Digital Beyond: Estate Planning for Electronic Assets.” Trusts & Estates 150 (9): 66–70.

Colloway, Jim. 2013. “Websites for Bidding Farewell.” American Bar Association’s GP Solo 30 (3): 76–77.

Feltham, Tammi S., Glenn Feltham, and James J. Barnett. 2005. “The Dependence of Family Business on a Single Decision-Maker.” Journal of Small Business Management 43 (1): 1–15.

Hopkins, Jamie P. 2013. “Afterlife in the Cloud: Managing a Digital Estate.” Hastings Science and Technology Law Journal 5 (2): 234–235.

Ip, Barry, and Gabriel Jacobs. 2006. “Business Succession Planning: A Review of the Evidence.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 13 (3): 326–350.

Karas, Tania. 2012. “Protecting Your Virtual Estate” SmartMoney.com. marketwatch.com/story/protecting-your-virtual-estate-1341944282513.

Korzec, Colin, and Ethan A. McKittrick. 2011. “Estate Administration in Cyberspace.” Trusts & Estates 150 (9): 61–65.

Malinen, Pasi. 2004. “Problems in Transfer of Business Experienced by Finnish Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 11 (1): 130–139.

Meserve, Jason. 2003. “Digital Asset Management Becomes a Reality.” Network World 20 (45): 19.

Nonaka, Ikujiro, and Hirotaka Takeuchi. 1995. The Knowledge-Creating Company. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Null, Christopher. 2013. “How to Get Your Online Assets in Order Before You Die.” PC World 31 (8): 23–24.

Ray, Chelsea. 2013. “‘Til Death Do Us Part: A Proposal for Handling Digital Assets after Death.” Real Property, Trust, and Estate Law Journal 47 (3): 583–615.

Sambrook, Sally. 2005. “Exploring Succession Planning in Small, Growing Firms.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 12 (4): 579–594.

Sharp, Crystal. 2013. “Managing Your Digital Legacy.” Online Searcher 37 (6): 43–48.

Smith, Shandra Hill. 2012. “Don’t Forget Your Digital Estate Plan.” Black Enterprise 43 (3): 23–24.

Walker, Michael, and Victoria Blachly. 2011. “Virtual Assets.” American Law Institute - American Bar Association continuing legal education course of study.

Citation

Hopkins, Jamie P., Ilya Lipin, and John Whitham. 2014. “The Importance of Digital Asset Succession Planning for Small Businesses.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (9): 54–62.