Journal of Financial Planning: August 2019

Jonathan Guyton, CFP®, is principal of Cornerstone Wealth Advisors Inc., a holistic financial planning and wealth management firm in Edina, Minnesota. He is a researcher, mentor, author, and frequent national speaker on retirement planning and asset distribution strategies.

Author’s acknowledgement: I appreciate my colleague, Sara Kantor, CFP®, for encouraging me to choose the ‘as-if retirement’ as the subject of this article.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

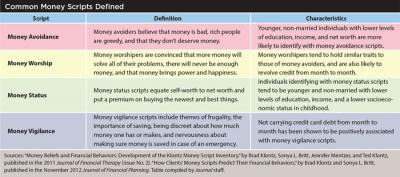

It’s fascinating how latent money scripts can intensify around a client’s transition into retirement. For those who have done a good job balancing saving and spending, money scripts of scarcity and/or vigilance can strangle the best-laid (and successful) planning, if not choke off the retirement transition altogether.

No doubt you’ve seen this situation before: a few years after saying she wants to retire in two to three years and being advised she is on track to make this happen, a client still says, “It would be nice to retire in two to three more years.” Or the couple where a wife has always looked forward to traveling in retirement who, post-retirement, begins a regular refrain about her spouse not wanting to spend the money to do so, even though they otherwise take little from their retirement savings.

Such deep-seated fears and beliefs are, of course, more than hurdles to simply “get over.” They can feel like mountains in one’s path with no perceptible pass-through or way around. The implied prudence masks their insidious seduction: “Even if I do already have enough money, working another year won’t make me any worse off.” And, “If we hold off spending money now, we’re even less likely to run out later.”

Far from being benign, this can be hard stuff that will not easily recede without intentional exploration and, probably, the unmasking of some nasty demons. For most of us, money is indeed a magnet that both attracts and displays what lies far below the surface. No wonder it can seem easier to just stay “stuck.”

Sometimes, though, changing what a client sees—financially—can create the movement that helps him or her find a way forward. Even if the client isn’t ready for his retirement transition, his money can begin to look and behave as if it already has. This is the “as-if retirement.”

Defining the “As-If Retirement”

Simply put, the “as-if retirement” organizes and utilizes client retirement assets as if earned income has stopped or decreased as planned. From the client’s perspective, it separates the financial transition from the anticipated (and possibly feared) changes to real life. Financially speaking, things look like the client is actually retired.

It’s important to clarify that this is far more than a mere reallocation of retirement assets, which should have happened two to three years ago, if not more. In addition, nothing in the “as-if retirement” creates any taxable events.

Consider Leonard’s situation. Having turned 65 several months ago, he is more than a year beyond his original goal to retire by age 64. In fact, when he turned 60 he actually told us, “In two to three years, I don’t want to still be saying that I’m going to retire in two to three years.” Apparently, he knew himself well! Yet, Leonard is well on his way to living that story.

He acknowledges not knowing what it would feel like to “have enough money.” How could he when—like all pre-retirees—most aspects of his life look and feel like the many years when he knew he was on track but not “there” just yet. At least in some ways, most people who eventually succeed at saving enough for retirement have lived and spent for decades knowing full well that they didn’t yet have enough. So, it’s understandable that when the calculus of planning says, “You’re there,” the right brain—literally—can’t yet wrap its head around this.

In his intellectual left brain, Leonard understands that he had more than enough money at age 64. Specifically, he had confidence in the amount of his core spending need in retirement. At that point, his assets were sufficient to cover the $252,000 needed to fund his “income bridge” until $42,000 in annual Social Security income began in six years. The other $42,000 in gross annual income Leonard needs to fund his core spending will follow dynamic withdrawal policies using a portfolio of 60 percent to 70 percent equities.

“I’ve always had some year-to-year fluctuation in my income,” he said then, “so being a little flexible in my retirement spending will be nothing new. Anyway, that’s what my discretionary money is for, right?” Leonard was indeed right. He was referring to his $200,000 of assets not needed for either his bridge portfolio or core portfolio.1 Now that he’s 65 years old, his Social Security benefits will begin in only five years.

Yet Leonard continues to work. Obviously, it’s not about the money.

Tellingly, he reveals that he enjoys seeing his $1.25 million continue to grow. And now, more than a year since turning 64, thanks to additional retirement savings, modest investment returns, and most significantly—over a year’s less time to “bridge,” his discretionary assets are greater still.

As we talk again about both left-brain and right-brain aspects of the concept of “enough money,” we suggest that Leonard consider a shift in how he sees his retirement nest egg; that we re-organize those retirement assets as if he were now retired.

Step One: Create Bridge, Core, and Discretionary Portfolios

Implementing Leonard’s “as-if retirement” involves two steps. First, create three distinct retirement portfolios: bridge, core, and discretionary.

For his bridge portfolio, journal $210,000 of Leonard’s assets into a new account to be invested conservatively because it will pay itself out over the next five years until his $42,000 annual Social Security benefits begin. Another $793,000 funds his core portfolio to produce $42,000 of sustainable, gross annual income at a 5.3 percent initial withdrawal rate under the dynamic withdrawal policies.2

Journal another $325,000 of his existing after-tax and IRA assets to new brokerage and/or IRA accounts to which Leonard will add $468,000 from his 401(k) plan at retirement. This leaves about $300,000 for his discretionary portfolio comprised of his remaining after-tax and/or IRA assets (notice this is about $100,000 more than a year ago). It is here where any future Roth IRA conversions should occur, so that their eventual use would not cause the double-whammy of being taxable and also causing more Social Security income to be taxed. Since Leonard may choose to spend most (or all) of this in the next 15 to 20 years, invest his discretionary portfolio more conservatively than his core portfolio, but more aggressively than his bridge portfolio.

Although these core and bridge portfolio amounts will satisfy Leonard’s sustainable, after-tax retirement income need, the mix of pre-tax, after-tax, and Roth assets for each portfolio will vary based on each client’s net income need and their unique tax mix of assets.

Three general points on this:

For both singles and couples, be wary of tax minimization prior to collecting full Social Security that unnecessarily increases those benefits that are taxed at 22 percent.

For couples, be careful that tax minimization when both spouses are alive does not create a cruel tax surprise when the survivor files as a single taxpayer given the IRA balance that will still be subject to minimum distributions in ever-rising percentages.

Should a change in tax-efficiency planning deem it wise to alter the tax mix of a portfolio, you can always journal/shift assets as appropriate at that time.

From Leonard’s perspective, the first real change he will notice is no longer seeing his entire nest egg in a single “accumulation” portfolio. There are now three portfolios, each with a different purpose, objective, and investment strategy for his retirement years.

For both Leonard and his financial planner, it will be infinitely easier to assess how he’s doing. At any point, it’s clear whether his bridge portfolio is over- or under-funded as the clock ticks toward his age 70 Social Security start. His separate core portfolio will allow us to easily calculate Leonard’s withdrawal rate and determine if/when any adjustments are needed under the dynamic withdrawal policies. Finally, the separate discretionary portfolio will help Leonard clearly see where he stands, as he considers spending decisions beyond his normal retirement needs.

Step Two: Turn on the Income Spigots

The second step in the “as-if retirement” is to turn on the bridge and core income spigots. Since Leonard continues to work, however, this income flows into his discretionary portfolio. At least quarterly, the amounts that Leonard would receive if he were retired are journaled into the corresponding accounts of his discretionary portfolio, as if he were retired.

The only difference is that these are not taxable events (as nothing is sold) since Leonard does not receive any of this as income. However, he sees his money moving at least quarterly; his portfolio reports show distributions from two portfolios and deposits into the other. And, this is done in the exact amounts as if he were retired.

To us as financial planners, there is nothing new in what’s happening compared to what occurs for actual retirees. Yet, this is all new for Leonard. After all, he has never been retired. But by seeing the mechanics of his retirement income in operation, an aspect of any “not enough money” fear is eliminated.

Will this be enough to overcome his remaining scarcity fears? Will he retire sooner than he otherwise might have? Only time will tell. However, these movements transition Leonard’s accumulating retirement assets to their intended purpose. And, there is no telling what else may become unstuck and begin to move beneath the surface, as his money begins to serve him in these new ways.

Endnotes

- For more on bridge, core, and discretionary portfolios, see the following Journal of Financial Planning articles by Jonathan Guyton: “Bridges to Social Security” (June 2015); “When an Ounce of Discretion(ary) Is Worth a Pound of Core” (February 2013); and “Science, Behavior, Art, and ‘Nudges’” (February 2011). Available at FPAJournal.org.

- For more on dynamic withdrawal policies, see “Decision Rules and Maximum Initial Withdrawal Rates,” by Jonathan Guyton and William Klinger in the March 2006 Journal of Financial Planning.

LEARN MORE:

Continue the Discussion

Join Journal contributors for the monthly Journal in the Round live webinar, where they will continue the discussion on how to apply behavioral finance knowledge to actual client situations.

Visit Learning.OneFPA.org and click on “Online Programs” to register.