Journal of Financial Planning: August 2022

Executive Summary

- This paper explores the complexities involved in the estate planning process for blended families and offers guidance for financial planners based on the principles of financial psychology.

- Theoretical frameworks from the field of psychology offer insights into the formation and development of blended families and some of the unique challenges they face.

- It is important for financial planners to recognize how conflicting interests from current and former family members impact a client’s emotions and financial decision-making.

- Financial planners could benefit from understanding how to take a more comprehensive approach to helping clients recognize their money beliefs and biases by integrating financial psychology into the estate planning process.

- Financial psychology tools can help financial planners better understand blended families’ unique challenges.

Mikel W. A. Van Cleve has over 18 years of experience in financial planning. He uses his expertise to serve others by developing digital solutions and educational content focused on improving financial wellness within the military community. Mikel is a graduate student at Creighton University studying financial psychology and behavioral finance.

Bradley T. Klontz, Psy.D., CFP® is an associate professor of practice in financial psychology at Creighton University Heider College of Business and a managing principal at Your Mental Wealth Advisors. He has authored eight books on the psychology of money, including Psychology of Financial Planning: The Practitioners Guild to Money & Behavior and Facilitating Financial Health.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on images below for PDF versions

The landscape of American families has changed over the years. This shift has led to more diverse and complex financial planning needs. It is estimated that more than 50 percent of Americans have been or will be included in a blended family at some point in their lifetime (Oppenheimer & Co. Inc. 2021). Blended families can be defined as families in which one or both spouses have children or stepchildren from previous relationships (Hamilton and Blazek 2007). Sometimes there is more than one former partner, and there could be children from each past relationship. This adds to the complexity of estate planning, which involves making decisions about who receives certain assets and/or takes on certain responsibilities upon an individual’s incapacitation or death (Herzberg 2022).

For financial planners to successfully navigate the complexities of a blended family in the estate planning process, it’s helpful for them to understand the psychology of money and family systems. This includes being aware of how blended families form and operate, actively listening to understand clients and their emotions, and knowing how financial psychology tools can be incorporated to help clients. Money is a central resource for well-being, and as a result, it has a significant impact on relationships within families (Raijas 2011). This can be especially true in blended families, which often face additional challenging dynamics. For example, when a parent shows preferential treatment to one child over another around money, which is not uncommon when blending biological children and stepchildren, this can create parent–child unions that damage relationships and lead to conflict (Sanner, Ganong, and Coleman 2020). This conflict may become even more apparent as couples make decisions on how to leave assets to their kids, stepkids, and spouse.

The traditional educational curriculum has left planners ill-equipped to identify and work with these psychological dimensions. While they can impact all of the financial planning processes, many of these issues come to the foreground in the estate planning process, where key financial, family, and legacy decisions are made. In an attempt to help bridge this gap, this paper explores: (a) common issues facing blended families, (b) blended families and money, (c) blended family estate planning, (d) the psychology of blended family development, and (e) how financial planners can assist blended families with estate planning.

Common Issues Facing Blended Families

Blended families face some common challenges. As a system, a challenge faced by one member of the family will have an impact on all the other family members (Sanner, Ganong, and Coleman 2020). For example, if a child is grieving the loss of the old family, it can hurt the experience of all the other family members. Family systems theorists argue that change and restructuring require adjustment because systems are typically stable (Golish 2003). Healthy blended families can adapt and adjust, whereas other blended families may struggle.

Sanner, Ganong, and Coleman (2020) pointed to one of the biggest issues within blended families—the impact of parent–child relationships, particularly when a parent shows preferential treatment to one child over another. This is not uncommon with blended families since the biological parent and child share more history. Children in more complex living environments appear to be negatively impacted in the areas of economic well-being and educational attainment (Sanner, Ganong, and Coleman 2020). Adding in half-siblings also puts kids in this type of environment at higher risk (Sanner, Ganong, and Coleman 2020). Finally, research shows that children living in blended families with open communication around family histories and dynamics experienced reduced uncertainty of living in a blended family environment, demonstrating communication as a key theme (Sanner, Ganong, and Coleman 2020). While there are challenges, families have the potential to emerge stronger as time goes by after facing stressful and challenging conditions (Brown and Robinson 2012). Healthy communication is the most commonly recognized factor in resiliency and the key ingredient in the development of relationships within blended families (Golish 2003; Brown and Robinson 2012).

Blended Families and Money

Money management can lead to conflict in families when members have different ideas about how to use it, and studies show that conflicts over money are a leading cause of divorce (Dew, Britt, and Huston 2012). Conversely, the perception that one’s spouse holds similar beliefs around money has been linked to positive feelings (Grable, Kruher, Bryam, and Kwak 2021). Studies comparing blended families to traditional nuclear families have found that blended family money management is even more complex (Raijas 2011).

Studies have shown that those who have been previously divorced are more likely to manage their finances independently from their new spouse. For example, one study found that 45 percent of spouses in a blended family prefer separate bank accounts with only 14 percent having at least one joint account (Raijas 2011). This is not surprising given that expectations of a permanent, lasting relationship may have eroded, causing partners in the relationship to be more cautious (Raijas 2011). This separation could cause issues with trust and acts of financial infidelity. In fact, 43 percent of Americans admit to having committed an act of financial infidelity (NEFE/The Harris Poll 2021). For example, one spouse might spend more money on a biological child versus a stepchild, and not divulge that information to their spouse for fear of an argument. Further research is needed to determine if the rate of financial infidelity would be higher for remarried couples. Given that divorce rates increase in subsequent marriages (Lewis and Kreider 2015), acts of financial infidelity may very well be higher in blended families.

A particular challenge in blended families is the common mentality that what’s mine is mine and what’s yours is yours (Hamilton and Blazek 2007). This mindset can become more pronounced as time passes, so remarried couples would benefit from addressing this as early as possible. However, it is important to address it in a manner that does not create further division (Hamilton and Blazek 2007). Financial planners need to understand their clients’ mindsets to avoid subconsciously projecting their beliefs about how money should be managed onto their clients; for example, assuming that once you become married, you are one unit and should combine all assets and managing of expenses to show unity and long-term commitment to one’s marriage. Depending on the family’s stage of development and/or unique values, such advice may be wholly inappropriate.

Blended Family Estate Planning

Research shows that estate planning for blended families involves additional complexities due to the many considerations that must be taken into account (Hamilton and Blazek 2007). When doing estate planning with blended families, financial planners need to learn how the clients view ownership of their assets and liabilities, and not make assumptions. This could include how they view owning assets individually, jointly, inherited assets, or a combination of all of these. The underlying issue in blended family estate planning, even if not openly discussed, involves which spouse is responsible for what costs and how the estate of the accountable spouse is impacted (Hamilton and Blazek 2007).

Challenges in Blended Family Estate Planning

Hamilton and Blazek (2007) and Herzberg (2022) identify several challenges financial planners face when discussing estate planning strategies with clients in blended families. They include: (a) how property should be owned, (b) how to title assets owned pre-marriage, (c) management of current expenditures, (d) avoiding unintentionally disinheriting kids, (e) wealth differences between remarried spouses, (f) handling of debts from a prior marriage, (g) child support arrangements, (h) balancing needs between spouse and biological children, (i) complexity of relationships between households, (j) how to divide the estate, (k) protecting assets from former spouses, (l) fair treatment of all children involved, and (m) how to name beneficiaries.

Because of the complexities involved, financial planners should take the time to understand a family’s dynamics. This includes being sensitive to possibly strained relationships that can happen between stepparents and stepchildren when a biological parent passes away, and if there is any indication of ill will, creating a plan that allows parties to amicably part ways upon death (Hamilton and Blazek 2007). For example, issues between a stepparent and stepchild could mean needing to recommend a plan that prevents anyone from feeling as if they could be left out. An example might include recommending an irrevocable life insurance trust for the kids and then a revocable living trust for the spouse, with the kids excluded (Hamilton and Blazek 2007). Client emotions often run high when decisions revolve around conflicting interests from biological children, stepkids, former spouses and partners, and a new spouse (Herzberg 2022). As such, it’s important clients be fully open and honest with financial planners about the reasoning behind their decisions.

The Psychology of Blended Family Development

The increasing number of blended family households and the unique challenges they face have been well documented. While researchers ignored blended families until the 1970s when divorce replaced a spouse’s death as the primary reason for remarriage (Golish 2003), in the past few decades, much has been learned about their strengths and challenges. Blended families are often faced with more complexities, such as pre-divorce stress, separation, restructuring of households, parent–child relationships, remarriage, blended family integration, and a stigma of blended families that is less than desirable (Brown and Robinson 2012).

Papernow (1993) developed a seven-stage cycle of development for blended families, known as the Stepfamily Cycle. The cycle sheds light on many of these complexities and is a helpful framework for financial planners. When working with a blended family, a financial planner would benefit from thinking about where in the cycle a blended family exists. While these stages are presented linearly, it is common for families to slip in and out of and repeat certain stages of the cycle (Papernow 1993). The seven stages of the Stepfamily Cycle are as follows:

The Early Stages

1. Fantasy Stage: In the fantasy stage, family members bring their illusions and desires to the new family resulting from (a) previous failures and the hope of becoming a successful blended family, (b) their family histories, and (c) a lack of understanding of blended family dynamics (Papernow 1993). These hopes, even if unrealistic, are often intensely held. Coming to terms with the reality and getting past any unrealistic expectations may require substantial work by clients, and if they hold onto their fantasies rigidly, they can become a roadblock to successful family integration (Papernow 1993).

2. Immersion Stage: As differences in family members’ desires and perspectives become more noticeable, children and stepparents may experience increasing pressure, confusion, and distress (Papernow 1993). Unrealistic expectations, including a belief that blended families should function like first-time families, can make these early challenges feel like disappointments. If shame and accusations prevent good communication, families may become stuck in a painful cycle of conflict and dissatisfaction (Papernow 1993).

3. Awareness Stage: Papernow (1993) identifies this as the most critical stage for the integration of the stepfamily. It involves an inquisitive, understanding assessment of one’s perceptions and needs and those of others in the family system. Self-acceptance and transparency start to take the place of uncertainty and doubt (Papernow 1993). Family members begin to create a more realistic view of the life they share. This understanding provides the foundation for shared decision-making in the middle stages (Papernow 1993).

The Middle Stages

4. Mobilization Stage: During this stage, it’s not uncommon for a highly emotional environment to follow as the blended family moves into more openly expressing their differences and trying to persuade each other over blended family issues (Papernow 1993). This often involves the stepparent taking a strong position in one or more areas. Some families struggle to move past this stage and may cycle back to the confusion in the immersion stage. Unsuccessful blended families do not make it past this stage (Papernow 1993).

5. Action Stage: The action stage is a challenging period in which the family has enough information to implement new guidelines, develop new family customs, and recognize new family activities (Papernow 1993). Biological bonds begin to open up to make room for more inclusive blended relationships. A new center ground is constructed leaving some former ground from prior family systems intact (Papernow 1993).

The Later Stages

6. Contact Stage: At this stage, the blended family has reached a honeymoon period (Papernow 1993). Clear and open communications now characterize blended relationships. A comfortable stepparent role has been set and accepted by members of the family. A strong awareness process should continue to address new challenges and further strengthen the stepparent role (Papernow 1993).

7. Resolution Stage: In the final stage, the new system of bonds has become a fully-operating blended family (Papernow 1993). Family roles now shift easily within the group. Blended family boundaries are more adaptable than in first-time families, and biological bonds remain special and distinct. The middle ground has become secure in most blended family relationships, providing a solid sense of family (Papernow 1993). Children see themselves as members of two households and feel nurtured by the many relationships and values with which they are presented (Papernow 1993).

The length of time it takes for a blended family to progress through the stages can vary, but on average, families will spend two to three years in the early stages, another two to three years in the middle stages, and then one to two years in the later stages (Papernow 1993).

How Financial Planners Can Assist Blended Families with Estate Planning

Estate planning for blended families is more complex than for traditional households, requiring a greater level of care and understanding by financial planners. It might include considerations such as creating a prenuptial or postnuptial agreement, wills, powers of attorney, a qualified terminable interest property (QTIP) trust, or an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT). While these and other strategies are all logical steps to consider, there is an emotional aspect to the estate planning process that many financial planners fail to take into consideration. What follows is a blended family scenario and tools that financial planners can use to provide more effective financial planning services.

Using Diagrams to Help Make Sense of Blended Families and Their Dynamics

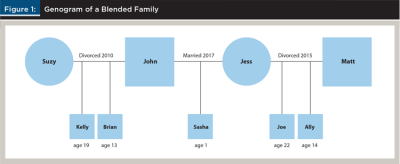

John and Jess, married in 2017, have one child together, Sasha, who recently turned 1. John was previously married to Suzy for 12 years, and they divorced in 2010. They had two children together, Kelly, age 19, and Brian, age 13. John and Suzy share custody of Brian, who goes back and forth between the households every other week. Jess was previously married to Matt for seven years, and they divorced in 2015. They had two kids together, Joe, age 22, and Ally, age 14. Jess and Matt share custody of Ally, who rotates homes on the same schedule as Brian. Before even considering the quality of the relationships between the family members, this scenario is a good example of the complexity of a blended family system. Visual aids can be helpful for both the financial planner and the client. One such visual aid is a genogram. A genogram is a graphical depiction of the relationships within a family system. Therapists often use it to provide awareness to clients about their family’s past (Wrenn 2019). This family dynamic is illustrated in the genogram in Figure 1.

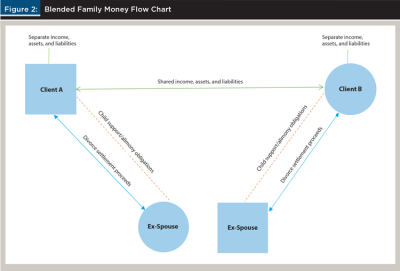

A diagram can also be useful to see how money intersects with the relationships within the family genogram. Figure 2 illustrates the typical flow of money after a divorce and into a new blended family and can be adapted by a financial planner to make sense of a family’s money flow.

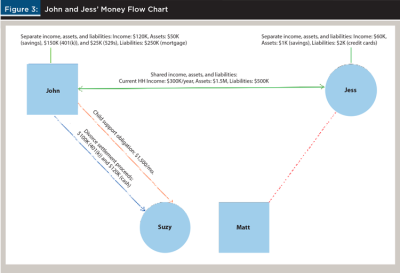

Based on the above model, Figure 3 shows an illustration of John and Jess’ money flow situation when they first entered their marriage and how it looks today with their shared income, assets, and liabilities. We see that John sends $1,500 per month in child support to Suzy and will continue to do so until Brian graduates from high school. Suzy was a stay-at-home parent, so John gave her half of his 401(k) plan and $120,000 in cash as part of the divorce settlement, which included half of a joint savings account and all the equity from the sale of their home. Jess, on the other hand, did not want Matt to pay child support because she feared it would damage the co-parenting relationship. Jess also did not receive any assets as part of the divorce settlement with Matt and did not have much in savings when she and John married. On the other hand, John came into the marriage with Jess with over $50,000 in savings, $150,000 invested in his 401(k), and 529 plans set up for both of his biological kids. John also owned a home while Jess was renting an apartment, so Jess moved in with John. They have since sold that home and built a home together titled in both their names. They’ve also collectively accumulated quite a bit more in wealth since marrying.

In their meeting with their financial planner, John and Jess expressed their wishes to have some assets owned jointly but keep others separate, and it quickly became apparent to their financial planner that conflicts have occurred over the matter. Their biggest concerns have been the perceived imbalance in the amount of money spent on and saved for biological children versus stepchildren. This includes the desire to ensure no child feels left behind or financially disinherited, while also making sure the surviving spouse is well taken care of should one spouse pass away. The traditional approach of leaving all assets to a surviving spouse with the kids as contingent beneficiaries will not work in a blended family scenario, given the new spouse would receive all assets and then could leave everything remaining upon their death to their biological children. If there are any strained relationships with stepchildren, this could become a very real scenario.

Another major issue in the case of John and Jess is that Jess resents Brian because of the amount of child support John sends Suzy and does not like when John spends any additional money on Brian. Even though the child support payment is technically made by John, Jess feels like she is also paying it since it takes away from their household income. The pressure for John to hide his spending on Brian and commit financial infidelity increases, as a result, and so does his desire to ensure Brian and Kelly are well taken care of should he pass away. At the same time, John also wants to make sure Jess is well taken care of should he pass before her. Balancing these wishes, along with the emotional turmoil and conflict John and Jess both feel, presents additional complexities in the estate planning process that traditional planning does not address.

With the heightened level of emotions involved in all these decisions, Jess may feel untrusted or that her kids are being left out if John asks for a postnuptial agreement. She may feel as if John thinks they might get divorced in the future versus being all-in with the marriage. Jess might also have negative feelings about John’s kids having college savings plans and her kids not having anything yet. John, on the other hand, might feel like he had certain things in motion already and certain plans for the legacy he wants to leave his children. He may feel pressure from Jess to change those plans, which could be a source of emotional turmoil for John. If a financial planner does not understand this dynamic or have a full understanding of the emotions involved, they may make recommendations that damage trust with their clients or cause further marital conflict. These types of complex family systems issues can feel overwhelming for a financial planner, and diagrams such as those above can be helpful in the financial planning process.

Integrating Financial Psychology Tools into the Stepfamily Cycle

Financial planners can help clients recognize what stage of blended family development they are in and how it may impact their estate planning decisions. Just the explanation of the stages can be beneficial as it can normalize many of the blended family struggles and challenges. Financial planners who understand this development, along with the theoretical basis of family systems theory, will be better positioned to provide sound estate planning strategies for their clients. The following strategies can be used by financial planners to work with blended families based on their place in the Stepfamily Cycle (adapted from Papernow 1993). It is important to note that across all stages, there may be times when a financial planner should refer clients to a mental health professional, and as such, this matter is also discussed.

The Early Stages

At this stage, it may be difficult for the financial planner to get a clear picture of family dynamics and make recommendations that satisfy both clients’ desires. It may be important for the financial planner to draw attention to desires for something that’s not possible. For example, one spouse may desire everyone to be treated equally when it comes to passing on assets, but child support obligations, asset types, and ownership may limit distribution strategies. When identified, the financial planner can provide information that could help put those desires in perspective around what’s possible. While not acting in the role of a therapist, the financial planner could also acknowledge and normalize the losses involved for the family if the family expresses them. For families who are experiencing high levels of conflict or dissatisfaction, it may be appropriate for the financial planner to refer them to a mental health professional.

The Klontz Money Scripts Inventory (KMSI)

An exercise financial planners could use with clients in the early stages is the Klontz Money Scripts Inventory (KMSI). The KMSI was designed to measure beliefs about money (Klontz, Britt, Mentzer, and Klontz 2011) and could be beneficial for clients to gain a deeper understanding of their own money beliefs as well as those of their partner. It groups clients into four categories: (1) Money Worship, (2) Money Status, (3) Money Avoidance, and (4) Money Vigilance. The KMSI also provides financial planners with better insights into their clients’ money beliefs. Spouses can benefit greatly from engaging with the KMSI separately and then reviewing each other’s results. Unlocking beliefs and biases toward money can help all parties involved better understand differences in money behaviors and actions needed to move forward in the estate planning process.

The Middle Stages

In the middle stages, financial planners may find that the most pressing issues for their clients are aired out and emotionally charged. For example, clients may start to realize by this point that not everything is always going to be equal or fair with the kids, and one or both may not be happy about it. The clients could even start arguing in front of the financial planner. The financial planner will need to navigate carefully to avoid appearing to take sides or causing more conflict.

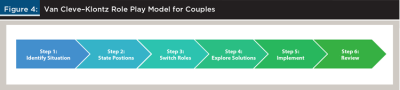

Financial planners could use a technique called behavioral rehearsal or role-playing during the middle stages, which is a cognitive behavioral therapy technique for modifying or enhancing interpersonal skills (American Psychological Association 2022). This exercise would involve playing out a given scenario, which helps clients see the impact of different estate planning scenarios to help facilitate a decision on the best strategy moving forward. Financial planners can use the Van Cleve–Klontz Role Play Model for Couples to help facilitate the exercise (see Figure 4).

Step 1: Identify Situation. In step one, the financial planner and clients identify the issues or challenges they want to role-play. The financial planner lays the ground rules for the discussion and the goal of gaining a better understanding of what goals the clients hope to achieve. In the example of John and Jess, the financial planner is aware of the tension they have around the topic of how much money is going to be left, and in what amounts, for their respective children.

Step 2: State Positions. The process begins with each client taking a turn to state their position on what they want and what they hope to achieve. The financial planner asks John and Jess, in turn, to talk about what they want to see happen. At this stage, the financial planner models active listening, reflecting back to each person what the planner thought they were saying, while their partner listens. John says he would like to leave an unequal amount to the kids based on assets brought into the marriage and relationship dynamics, but Jess wants everyone to be treated equally.

Step 3: Switch Roles. In this step, John and Jess are going to switch roles and pretend they are the other person. The financial planner has them even switch chairs to anchor the shift. This step is designed to facilitate a deeper understanding of each partner’s views.

Jess (Playing John): I’d like to ensure that my two biological kids receive the bulk of my assets after we are both gone. If I die first, I want to know you are taken care of, but ensure they receive everything that was mine beyond your needs.

John (Playing Jess): I’d prefer that all the kids receive an equal share of the assets after we both pass. We are working together to provide for the family.

Jess (Playing John): I understand, but because I came into the relationship with substantially more in assets, and had discussed these with my kids already. I feel it is only fair they receive more. Plus, I do not want them to resent you or your kids later because of it.

John (Playing Jess): My kids are just as important and we are all one family now. Things change, so our plans should, too.

Jess (Playing John): Your oldest son has never lived with us, and I do not know him at all. Why would I want to leave him so much money? Why not just give him part of whatever you accumulate between now and then?

John (Playing Jess): How am I supposed to tell my son he isn’t as important because he is older and never lived with us?

Jess (Playing John): (chuckles under her breath) I can tell him for you if you’d like.

The role-play is designed to help John and Jess begin to understand each other’s viewpoints better. The financial planner also gains a better understanding of the family dynamics and what is important to each client.

Step 4: Explore Solutions. In step four, the financial planner and clients discuss the role-play and how they feel about things. The financial planner attempts to gain agreement from clients to implement certain recommendations in the estate plan. At this point, the financial planner may ask the clients if they have any ideas on how to create a win-win solution. If the clients are not sure, the financial planner might give them some homework to read up on a couple of estate equalization techniques or provide such information directly. Role-play could continue if the clients are still struggling to understand each other’s positions and reach an agreement. If the clients are still entrenched in their positions, the financial planner may ask them to think about it and follow up with them later. If they continue to be at an impasse around the situation, the financial planner might recommend a couple’s therapist who could help them gain resolution around the issue.

Step 5: Implement. In the case of John and Jess, the role-play confirmed that they knew each other’s positions and they were ready to move forward with implementing a solution. The financial planner made some recommendations that could both preserve John’s assets for his kids while ensuring Jess’s kids are equally cared for by recommending they use life insurance as an estate equalization technique. In this case, the financial planner suggests they have an attorney establish a QTIP and set up an ILIT. The couple agreed to move forward with this plan and implement it.

Step 6: Review. Step six would be covered during regularly scheduled review sessions. If either John or Jess becomes confused about the plans, they can always revisit the role play model to simplify and play out the scenario.

Blended Family Estate Planning Conversation Exercise

Another exercise financial planners could use during this phase is the Blended Family Estate Planning Conversation Exercise (see appendix A). This exercise is an adaptation of the Conversation Intervention (Klontz and Klontz 2016) that focuses on creating open and honest communication between spouses around emotionally charged financial topics. Planners could use this exercise to help open the communication lines between spouses before recommending an estate planning strategy. The premise is to have couples set aside time for an honest discussion around things that have influenced their money beliefs, how they want to address their estate planning goals, and things they would like to improve upon financially within their relationship, as it pertains to their long-term planning.

The Later Stages

By the time clients reach the later stages, they should have a clear understanding of their family dynamics and be able to work together to create a plan that satisfies the majority of their needs. Financial planners typically will not need to focus as much on fostering good communication between clients or have to navigate emotional conflicts within the family. This does not mean that financial planners will not still face resistance from their clients. In the later stages, financial planners can use a technique called motivational interviewing (MI).

At some point in the financial planning process, it is normal for clients to resist the advice and recommendations provided by financial planners. According to Klontz, Kahler, and Klontz (2016), clients often seek advice but then resist it due to ambivalence, internally contemplating the positives and negatives of the action. Miller and Rollnick (2012) suggested MI can help overcome ambivalence and avoid creating additional resistance. Financial planners who understand and recognize when resistance is taking place and tailor their communication style and interviewing in a manner that fosters self-discovery by the client can help clients feel engaged and empowered in the estate planning process. A hypothesis that needs testing is that ambivalence and resistance to change during the estate planning process are higher in the early and middle stages of the Stepfamily Cycle, which could be attributed to the significant amount of change these families have already experienced while forming as a blended family.

One of the key tenets behind MI is conversations about change (Miller and Rollnick 2012). The typical response from a financial planner might be to argue for the side of change. However, when someone is ambivalent, taking the side of change is likely to create more resistance in the client. Conversations typically involve three communication styles: (1) directing, (2) guiding, and (3) following (Miller and Rollnick 2012). The directing style involves providing facts, education, and recommendations; the following style involves active listening skills; and the guiding style falls in the middle and involves good listening skills and providing recommendations as needed, and this is the sweet spot for MI (Miller and Rollnick 2012). With this in mind, the financial planner could use the following types of questions to engage their clients in change talk.

Motivational Interviewing Questions

- Why are you considering a change?

- What is keeping you from making the change?

- What steps might you take to change?

- What are the top three benefits of changing?

- What are the downsides of changing?

- How important is the change?

- How confident are you in your ability to change?

(Adapted from Miller and Rollnick 2012)

Referral to a Mental Health Professional

Regardless of what stage a blended family is in, the financial planner may need to refer clients to a mental health professional. This can be particularly true if it becomes obvious that family or individual counseling is needed, due to conflict, or if one spouse suffers from certain money disorders that would need to be diagnosed and treated by a mental health professional. Not addressing marital conflict and/or money disorders could cause issues in the estate planning process. Financial planners should understand their boundaries when it comes to incorporating financial psychology exercises, engage mental health professionals when needed, and avoid conflicts of interest such as providing mental health counseling and money management to the same client, as could be the case for those qualified in both the financial planning and mental health fields.

Conclusion

Estate planning for blended families is complex. Traditional financial planning methods are insufficient as they fail to take into consideration the emotional aspect of the decisions a blended family must make. To best serve their clients’ needs, financial planners would benefit from understanding the family dynamics common in blended families as well as common issues that can impact the financial planning process. Many of these issues become known in the estate planning process, with family members having different beliefs about what should be done and, at times, competing agendas. By utilizing strategies from the emerging field of financial psychology, financial planners can better serve their clients and help them navigate the financial planning process. Financial planners who take the psychology of financial planning into account during the estate planning process can help their clients address both the emotional and practical aspects related to blended family estate planning.

Citation

Van Cleve, Mikel, and Bradley Klontz. 2022. “The Psychology of Estate Planning with Blended Families: How Financial Planners Can Better Help Blended Families Develop an Estate Plan That Works.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (8): 74–88.

References

American Psychological Association. 2022. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/behavior-rehearsal.

Brown, Ottilia, and Juliet Robinson. 2012. “Resilience in Remarried Families.” South African Journal of Psychology 42 (1): 114–126.

Dew, Jeffrey, Sonya Britt, and Sandra Huston. 2012. “Examining the Relationship Between Financial Issues and Divorce.” Family Relations 61: 615–628.

Casey, Gerald A. 1973. “Behavior Rehearsal: Principles and Procedures.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 10 (4): 331–333.

Golish, Tamara D. 2003. “Stepfamily Communication Strengths: Understanding the Ties That Bind.” Human Communication Research 29 (1): 41–80.

Grable, John, Michelle Kruger, Jamie Lynn Byram, and Eun Jin Kwak. 2021. “Perceptions of a Partner’s Spending and Saving Behavior and Financial Satisfaction.” Journal of Financial Therapy 12 (1) 3: 31–50.

Hamilton, Gregory C., and James T. Blazek. 2007. “Avoiding Unintended Disinheritance.” Journal of Practical Estate Planning: 43–50.

Herzberg, Philip. 2022. “Navigating Estate Planning for Blended Families.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (1): 50–53.

Klontz, B.T., S.L. Britt, J. Mentzer, and P.T. Klontz. 2011. “Money Beliefs and Financial Behaviors: Development of the Klontz Money Script Inventory.” Journal of Financial Therapy 2 (1): 1–22.

Klontz, Brad, and Ted Klontz. 2016. “The Conversation Intervention.” Financial Psychology Institute. Unpublished exercise.

Klontz, Bradley, Rick Kahler, and Ted Klontz. 2016. Facilitating Financial Health. 2nd Ed. Erlanger: The National Underwriter Company.

Lewis, J. M., and R. M. Kreider. 2015, March 10. “Remarriage in the United States.” U.S Census Bureau. Accessed April 8, 2022. www.census.gov/library/publications/2015/acs/acs-30.html.

Miller, William R., and Stephen Rollnick. 2012. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd Edition. New York: Guilford Press.

NEFE/The Harris Poll. 2021. “Financial Infidelity 2021.” Accessed April 8, 2022. www.nefe.org/research/polls/2021/financial-infidelity-2021.aspx.

Oppenheimer & Co. Inc. 2021, April 7. “Wealth Management: Estate Planning for Blended Families.” www.oppenheimer.com/news-media/2021/insight/april/estate-planning-for-blended-families-print.aspx.

Papernow, Patricia L. 1993. Becoming a Stepfamily: Patterns of Development in Remarried Families. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Raijas, Anu. 2011. “Money Management in Blended and Nuclear Families.” Journal of Economic Psychology 32: 556–563.

Sanner, Caroline, Lawrence Ganong, and Marilyn Coleman. 2020. “Shared Children in Stepfamilies: Experiences Living in a Hybrid Family Structure.” Journal of Marriage & Family 82: 605–621.

Wrenn, Andi. 2019. “How to Use Genograms with Clients.” Association for Financial Counseling & Planning Education. Accessed April 9, 2022. www.afcpe.org/news-and-publications/the-standard/2019-4/how-to-use-genograms-with-clients/.

Appendix A: Blended Family Estate Planning Conversation Exercise

Instructions

- Schedule time with your spouse. Agree not to engage in “drive-by” estate planning conversations. Set a time and place to talk. Show up ready to listen and understand.

- Sit facing each other. Sit with your knees anywhere from a few inches to a few feet away from your partner, according to your comfort level.

- Pick a speaker and a listener.

- Use reflective listening. The speaker talks for one to two minutes. The listener listens, then summarizes what he or she has heard, without analyzing, interpreting, asking questions, or arguing. This is an incredibly challenging task for most people, especially when the issue is a hot topic like estate planning and/or the couple has had a history of conflict around the topic. The listener reflects on what he or she thinks was said. The speaker then (a) says “yes, that’s it” or (b) clarifies. If the speaker offers a clarification, the listener reflects again on what was said.

- Switch roles and repeat as needed. For this exercise, each person can take turns sharing their answer to each question.

- As needed, take a time out. Emotional flooding is poison to a relationship. When we are flooded, our thinking brain goes off-line, and we end up doing or saying something we regret. If your anger or frustration reaches a level six on a scale of 1–10, take a 10- to 20-minute time-out, during which you both examine your role in where the conversation went bad. Then come back together and start again.

Questions to discuss:

- What is your earliest money memory?

- Want is your most joyful money memory?

- What is your most painful money memory?

- How have your prior marriage(s) and former relationships impacted your thoughts and feelings about money?

- Name three money mistakes from your prior relationship(s) that you want to avoid repeating.

- Name three positive money outcomes from your prior relationship(s) that you would like to continue.

- What has been the most painful part of blending your family?

- What has been the most enjoyable part of blending your family?

- What are your estate planning goals?

- How important is leaving a legacy for your biological kids? Stepchildren?

- What are your biggest estate planning fears?

- Name one or more things you are willing to do differently around money to improve your current relationship.

- List three values that you would like to guide your family’s life.

- Name three things you appreciate and admire about your partner.