Journal of Financial Planning: August 2023

Executive Summary

- This study uses structural equation modeling to examine the relationship between the need for achievement, risk tolerance, and cryptocurrency holdings using the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS).

- Confirmatory factor analysis shows education and income are suitable measures of the latent construct of achievement but not self-employment status.

- The structural equation model results reveal that higher achievement led to an increase in risk tolerance, and an increase in risk tolerance led to an increase in cryptocurrency holding.

- The discussion highlights the need for personal financial planning to expand its theoretical base and for financial professionals to encourage clients to take on greater risk to achieve financial goals.

Jason N. Anderson, CFP®, CPA, is a lecturer in finance at the University of Kansas, owner of Gradmetrics, and a Ph.D. student studying personal financial planning at Kansas State University. Jason is interested in fintech, cryptocurrency, and student loan planning.

Derek R. Lawson, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor in the Department of Personal Financial Planning at Kansas State University, with research interests in behavioral finance, financial therapy, financial psychology, and relationship dynamics among couples. Lawson is also a financial planner at Priority Financial Partners in Durango, Colorado.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Note: Click on the images below for PDF versions

Risk is an essential concept for personal financial planning. Financial advisers and planners are required by regulation to investigate their client’s risk tolerance and steward assets under management (AUM) according to their client’s risk preferences. Practitioners regularly support the idea that risk-taking is a vital part of achieving financial goals, as it is believed that taking on risk can lead to greater returns. Indeed, the assumption is not without empirical support. For example, Jones, Howard, and Finch (2016) showed the importance of staying invested even during perceived risky events such as market swings and volatility. Accordingly, researchers have studied the how and why of individual risk-taking and its relationship to financial goal achievement (see Cai and Yang 2010; Chatterjee, Fan, Jacobs, and Haas 2017; Grable and Carr 2014).

Personality traits and their relationship to risk have also been explored to gain a holistic understanding of the factors that influence risk tolerance and risk-taking. For example, Grable and Carr (2014) explored the role of mediating factors such as “mastery” for risk tolerance, while Kanadhasan, Aramvalarthan, Mitra, and Goyal (2016) found a positive relationship between financial risk tolerance and self-esteem, personality type, and sensation-seeking. Grable (2008) proposed a conceptual framework for risk tolerance that included biopsychosocial, environmental, and precipitating factors (the biopsychosocial sphere includes personality traits). More importantly for this study, Cai and Yang (2010) studied the relationship between financial goal setting and risk tolerance using an achievement domain focused on capital acquisition. This study showed that financial goal clarity across the achievement domain significantly influenced risk tolerance. The core research question behind these studies is: what personality traits are present in a person who takes (or conversely, does not take) risk? The current study seeks to investigate achievement and its relationship to risk using the 2018 National Financial Capability Study (NFCS).

The second level of this study will go beyond the relationship between achievement and risk to study the impact of these factors on financial behavior. Although many financial behaviors could be investigated, this study focuses on the financial behavior of cryptocurrency holding precisely because many researchers view it as an intrinsically risky activity (Canh, Wongchoti, Thanh, and Thong 2019; Zhao and Zhang 2021). This second level of analysis provides additional insight into the role of achievement in risk-taking behavior.

Literature Review

This study’s literature review aims to bolster the theory proposed for the study, show that the selected variables are a good proxy for achievement as defined by learned needs theory, and uncover previous studies relating to achievement, risk-taking, and cryptocurrency holdings.

The theoretical framework for this study is based on learned needs theory, developed by Harvard psychologist David McClelland (Harvard n.d.; McClelland 1961). McClelland was interested in identifying the needs that drive human behavior. His research led to the development of learned needs theory, which identifies three dominant human needs (Harvard n.d.). The three basic needs are the need for achievement (nAch), the need for affiliation (nAff), and the need for power (nPow) (Black et al. 2019). The need for achievement is an individual’s motivation for task achievement and performance, the need for affiliation is the motivation to establish positive relationships, and the need for power is the need to control things and people. Learned needs theory derives from, and relates to, other important theories, including manifest needs theory, self-determination theory (the idea of autonomy in particular), social needs theory, and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Black et al. 2019).

The achievement component of learned needs theory has previously been used to study scholastic achievement, employment outcomes, and job satisfaction. Jenkins (1987) uses high school senior-year achievement to predict employment outcomes. Caplehorn and Sutton (1965) show a strong connection between the need for achievement and intelligence and performance in school. The need for achievement also surfaces frequently in the study of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is an inherently risky activity, much like the holding of cryptocurrency, making these studies especially relevant to the author’s selected financial behavior. Although limited to young adults living in the United Arab Emirates, Ryan, Tipu, and Zeffane (2011) uncovered a strong correlation between the need for achievement and entrepreneurial activity. Furthermore, Saif and Gha-nia (2020) also made this link, although their study is limited to entrepreneurs in China.

Achievement

McClelland (1961) discussed social status, race, and employment in their framing of the need for achievement concept. Accordingly, the current study uses education and income as proxies for the need for achievement. A previous Hu, Lasker, Kirkegaard, and Fuerst (2019) study used achievement test scores to indicate intelligence when it investigated the relationship between intelligence and race and ancestry. In addition to the weight placed on prestigious colleges and universities as a badge of success in both the United States and internationally, previous research has shown that selective colleges lead to greater earnings (Monks 2000). A study connecting many of these concepts was conducted by Bishop (1989), which investigated the causal connections between academic achievement in high school and payoff to college.

To the authors’ knowledge, learned needs theory has not yet been integrated into the financial planning literature based on a precursory literature search across popular financial planning journals, including the Journal of Financial Planning, Journal of Consumer Affairs, Journal of Family and Economic Issues, Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Journal of Financial Services Professionals, and Financial Services Review. The closest studies relating to personal financial planning have focused on the need for achievement’s relationship to entrepreneurship (Zeffane 2013; Saif and Ghania 2020). Learned needs theory has been used in other disciplines, such as psychology, economic development, and management. Since learned needs theory has yet to be integrated into the financial planning literature, its addition to the corpus of knowledge will be helpful.

Risk-Taking

The importance of risk to almost every facet of financial planning can hardly be underestimated. Many studies across the financial planning literature investigate the relationship between risk and various financial planning behaviors. Risk is a determining factor in savings withdrawal rates (Finke, Pfau, and Williams 2012), financial decision-making (Ryack, Kraten, and Sheikh 2016), and investment decisions (Masters 1989). Importantly, studies have shown that risk tolerance is a stable personality trait at the individual level (Van de Venter, Michayluk, and Davey 2012; Sahm 2007). Without the ability to change risk tolerance, the next best thing is understanding what variables influence a client’s risk tolerance.

Research from Mandal and Roe (2014) finds a relationship between aging and cognitive skills and risk. Namely, those with the highest and lowest cognitive skills have increased risk tolerance, and risk tolerance decreases with age. Interestingly, this study also briefly examines the relationship between risk tolerance and the share of risky assets, defined as the fraction of wealth spent on stock holdings (Mandal and Roe 2014). Bryant et al. (2003) link academic achievement and a common risky behavior: substance abuse. This study found a positive correlation between low levels of academic achievement and cigarette and marijuana use. This study provides an important empirical example of how academic success or failure can lead to risk-taking behavior.

Cryptocurrency

Cryptocurrency has recently received much attention from investors, regulators, and researchers. The study of cryptocurrency holding is essential in terms of the variables selected for this study, especially risk. However, studying cryptocurrency within personal financial planning could be more extensive. Kim and Hanna (2020) examined the relationship between investment literacy and cryptocurrency investment using the 2018 NFCS. The authors found that objective financial literacy was negatively associated with cryptocurrency holdings, whereas subjective financial literacy was positively associated with cryptocurrency holdings. Interestingly, the authors also found that investors in cryptocurrency had higher overconfidence measures than non-cryptocurrency holders. Subramaniam and Chakraborty (2020) investigate investor attention and cryptocurrency returns and found that for Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Ripple, investor attention increases returns and leads to price pressure at higher quartiles when prices are pushing the upper limits. For Litecoin, this pressure is found at all quartiles. Finally, Zhao and Zhang (2021) studied the relationship between financial literacy, investment experience, and cryptocurrency investment using the investor survey of the 2018 NFCS. They found that subjective financial knowledge demonstrated a significant positive relationship with cryptocurrency investment. Importantly for the current study, they also found that the holding of stocks and risky assets was positively related to cryptocurrency investments.

Hypotheses

This study has two hypotheses related to the variables of interest:

- (H1): higher achievement measures lead to higher risk-taking measures

- (H2): higher risk-taking measures lead to an increase in holding cryptocurrency as an investment

Methods

Data

The data used in this study is from the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS). The NFCS is a cross-sectional survey published by the FINRA Education Investment Foundation and administered every three years and surveys over 25,000 individuals (FINRA n.d.). The survey is designed to be representative of the general United States population given the appropriate weightings; however, the data cannot be used to interpret how individuals change over time. The NFCS consists of a state-by-state section and an investor survey. Variables from this study are taken from the merged 2018 state-by-state and investor surveys. While the 2021 state-by-state survey was available during the writing of this article, the 2021 investor survey was not. Therefore, the current study uses the 2018 NFCS. Since the cryptocurrency variable studied is found only in the investor survey, this study’s sample is limited to those participants (n = 2,003).

Variables

The variables for this study can be broken into three categories: measures of achievement, measures of risk, and financial behavior.

Measures of achievement. Measures of achievement will serve as a proxy for the need for achievement in learned needs theory and includes level of education, income, and entrepreneurship as an employment status. The education variable comes from the NFCS state-by-state survey question that asks, “What was the highest level of education that you completed?” The categories were not recoded but remained as: did not complete high school, high school graduate (regular high school diploma), high school graduate (GED or alternative credential), college with no degree, associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, and postgraduate degree. The income variable comes from the NFCS state-by-state survey question, which asks, “What is your household’s approximate annual income, including wages, tips, investment income, public assistance, income from retirement plans, etc.? Would you say it is…” The categories were not recoded but remained as: less than $15,000, at least $15,000 but less than $25,000, at least $25,000 but less than $35,000, at least $35,000 but less than $50,000, at least $50,000 but less than $75,000, at least $75,000 but less than $100,000, at least $100,000 but less than $150,000, and $150,000 or more. The entrepreneurship variable comes from the NFCS state-by-state survey question, which asks, “Which of the following best describes your current employment or work status?” The answers to this question were recoded as a dichotomous variable where 1 represents self-employment and 0 otherwise.

Willingness to take risk. The risk measure is taken from the NFCS state-by-state survey question, which asks, “When thinking of your financial investments, how willing are you to take risks?” Answers are selected on a 1–10 scale ranging from “Not at All Willing” to “Very Willing.”

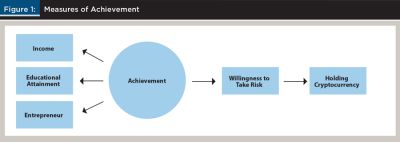

Financial behavior. The financial behavior variable is cryptocurrency holdings. This variable is generated from the NFCS investor survey as a dichotomous variable (cryptocurrency holding, 1, or not, 0) from the following question: “Have you invested in cryptocurrencies, either directly or through a fund that invests in cryptocurrencies?” A conceptual model of the relationships between the variables is shown in Figure 1.

Results

Data Analysis Procedure

Stata SE version 17.0 was used to clean data and create descriptive statistics and correlation tables. The structural equation model was conducted using MPlus version 8.8. Variables were first coded in Stata and then exported for analysis in MPlus. Responses of “Don’t know” and “prefer not to say” in the risk tolerance and cryptocurrency holding variables were coded as missing values. The risk tolerance variable had 12 observations deleted, and the cryptocurrency holding variable had 23 observations deleted.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

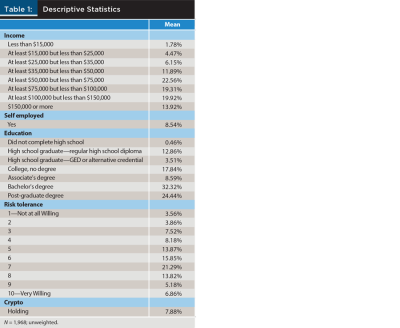

The descriptive statistics for the variables in this study are presented in Table 1. The distribution of the income variable skews toward those of higher income, which is unsurprising considering the study’s sample is restricted to individuals filling out the NFCS investor survey. Most of the sample fell into higher income brackets, with over 75 percent making at least $50,000 and 33.8 percent making more than $100,000 annually. The sample was also highly educated, with 56.8 percent having a bachelor’s degree or higher. Self-employed individuals represented a small portion of the overall sample at 8.5 percent. Importantly, slightly less than 8 percent of respondents in the sample report held cryptocurrency investments. A correlations table for the variables in this study is provided in Table 2.

Structural Equation Model Results

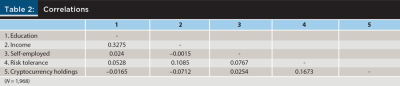

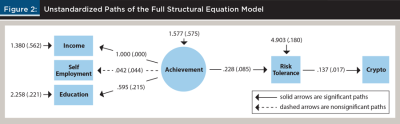

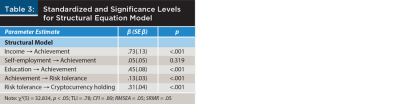

The first step of the analysis consisted of using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to fit the achievement latent variable in the model using the education, income, and self-employed variables. The initial run of the CFA model using education, income, and self-employment status was just identified. The standard errors of the model parameter estimates for education could not be computed even though a full SEM model ran successfully with the three variables (c2(5) = 32.834, p < .05; TLI = 0.78; CFI = 0.89; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.05). In this model run, standardized results for income (b =.73, p < .001) and education (b =.45, p < .001) were significant with high factor loadings, but self-employment was not significant. Standardized results show that a one-unit increase in income led to a .73 standard deviation increase in achievement. Income is a larger driver in the achievement latent construct than either self-employment or education. Also, a one-unit increase in achievement led to a .13 standard deviation increase in risk tolerance. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Finally, a one-unit increase in risk tolerance led to a .31 standard deviation increase in cryptocurrency holding. As such, Hypothesis 2 is also supported. Figure 2 shows the significant paths of the full structural equation model, and Table 3 shows the model fit statistics and results.

Discussion and Implications

As a nascent field, personal financial planning still needs to develop its theoretical foundation (Danes and Yang 2014; Overton 2008). The current study adds to the body of literature by introducing learned needs theory to the field of personal financial planning. In addition, investigating the topics at hand using this theory bolsters the field’s ties to disciplines such as psychology and management. Although a novel theoretical framework for both personal financial planning and the study of cryptocurrency, this study showed strong support for learned needs theory. These results, in turn, encourage the field’s continued integration of psychology into the financial planning process.

Both hypotheses were supported by the analysis. According to the results of the structural equation model, individuals with high achievement (as measured through income and education) may have higher risk tolerance levels and, therefore, cryptocurrency holdings. As in many personal financial planning studies, income plays an outsized role in the measurement of achievement.

One of the applications of better understanding risk tolerance through this study is to inform how a financial adviser might encourage a client to take on greater risk to achieve financial goals. Given that a general maxim within the field is “higher risk, higher return,” a prudent portfolio allocation to riskier assets could lead to increasingly positive financial planning outcomes. In an age where fewer individuals are retiring with the requisite savings, the concept of greater risk leading to greater return has never been more critical.

The assessment of learned needs theory in this study uncovers a personality profile that financial planners can use to identify clients who might take on greater risk and, consequently, an increased desire to hold riskier assets such as cryptocurrency within a portfolio. Of course, this is not to say all clients should own cryptocurrency—as it is an asset class with uniquely risky characteristics—as discussed in the literature review. However, the results of this study could help advisers identify when—and particularly for whom—cryptocurrency holding might make sense. Indeed, this study shows that achievement is a driver of financial behavior, and financial planners are constantly searching for such behavioral levers to encourage clients to take action toward their financial goals.

Limitations

Limitations in the data analyzed here give pause in generalizing the results of this study. As previously noted, the investor survey of the NFCS disproportionately represented respondents at higher income levels. Furthermore, the relatively limited sample sizes for cryptocurrency holders (n = 157) and self-employed respondents (n = 170) compared to the overall investor survey (and even state-by-state) sample indicate room for growth in the insights gleaned from the NFCS. Opportunities to create datasets with larger sample sizes in these two categories might lead to additional beneficial insights for researchers studying cryptocurrency holders.

Initial runs of the structural equation model indicated that correlating income and education might be justified. Indeed, this change improved model fit, but the authors decided against this change based on a review of McClelland’s development of learned needs theory, where education (i.e., discussions of Protestant versus Catholic education, educational mobility, etc.) and social status (analysis of the differences in need for achievement in upper-class versus lower-class environments) are separately discussed. In other words, testing these concepts separately made sense for a first pass at applying this novel theory in personal financial planning. Future studies could further investigate the correlation between education and income and how they jointly relate to risk and financial behavior.

Citation

Anderson, Jason, N., and Derek R. Lawson. 2023. “A Study of Achievement, Risk, and Cryptocurrency Using Learned Needs Theory.” Journal of Financial Planning 36 (8): 74–83.

References

Bishop, John H. 1989. “Achievement, Test Scores, and Relative Wages.” Cornell University 53.

Black, Stewart, David S. Bright, Donald G. Gardner, Eva Hartmann, Jason Lambert, Laura M. Leduc, Joy Leopold, James S. O’Rourke, Jon L. Pierce, Richard M. Steers, Siri Terjesen, and Joseph Weiss. 2019. Organizational Behavior. Houston: OpenStax.

Bryant, Allison L., John E. Schulenberg, Patrick M. O’Malley, Jerald G. Bachman, and Lloyd D. Johnston. 2003. “How Academic Achievement, Attitudes, and Behaviors Relate to the Course of Substance Use During Adolescence: A 6-Year, Multiwave National Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 13: 361–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.1303005.

Cai, Yi, and Yali Yang. 2010. “The Effect of Financial Goal and Wealth Change on Risk Tolerance: An Experimental Investigation.” Journal of Personal Finance 9: 148–169.

Caplehorn, W. F., and A.J. Sutton. 1965. “Need Achievment and its Relation to School Performance, Anxiety and Intelligence.” Australian Journal of Psychology 17 (1): 44–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00049536508255526.

Canh, Phuc C., Udomsak Wongchoti, Su D. Thanh, and Nguyen T. Thong. 2019. “Systematic Risk in Cryptocurrency Market: Evidence from DCC-MGARCH Model.” Finance Research Letters 29: 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.03.011.

Chatterjee, Swarn, Lu Fan, Ben Jacobs, and Robin Haas. 2017. “Risk Tolerance and Goals-Based Savings Behavior of Households: The Role of Financial Literacy.” Journal of Personal Finance 16 (1): 66–77.

Danes, Sharon M., and Yunxi Yang. 2014. “Assessment of the Use of Theories Within the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning and the Contribution of the Family Financial Socialization Conceptual Model.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 25 (1): 53–68.

FINRA. n.d. “Financial Capability Study: About the Study.” Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). Accessed January 27, 2022. www.usfinancialcapability.org/about.php.

Finke, Michael S., Wade D. Pfau, and Duncan Williams. 2012. “Spending Flexibility and Safe Withdrawal Rates.” Journal of Financial Planning 25 (3): 44–51.

Grable, John E. 2008. “Risk Tolerance.” In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. Edited by J. J. Xiao. New York: Springer Press: 3–19.

Grable, John E., and Nicholas A. Carr. 2014. “Risk Tolerance and Goal-Based Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 68 (1): 12–14.

Harvard. n.d. “David McClelland (1917–1988).” https://psychology.fas.harvard.edu/people/david-mcclelland.

Hu, Meng, Jordan Lasker, Emil O.W. Kirkegaard, and John G.R. Fuerst. 2019. “Filling in the Gaps: The Association Between Intelligence and Both Color and Parent-Reported Ancestry in The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997.” Psych 1 (1): 240–261. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/psych1010017.

Jenkins, Sharon R. 1987. “Need for Achievement and Women’s Careers Over 14 Years: Evidence for Occupational Structure Effects.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53 (5): 922–932. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.5.922.

Jones, Travis L., Steve P. Fraser, and J. Howard Finch. 2016. “Volatility and Targeted Portfolio Returns.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 27 (1): 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1891/1052-3073.27.1.122.

Kannadhasan, M., S. Aramvalarthan, S.K. Mitra, and Vinay Goyal. 2016. “Relationship Between Biopsychosocial Factors and Financial Risk Tolerance: An Empirical Study.” Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers 41 (2): 117–131.

Kim, Kyoung T., and Sherman D. Hanna. 2020. “Investment Literacy, Overconfidence and Cryptocurrency Investment.” The 2020 Association for Financial Counseling & Planning Education (AFCPE).

Mandal, Bidisha, and Brian E. Roe. 2014. “Risk Tolerance Among National Longitudinal Survey of Youth Participants: The Effects of Age and Cognitive Skills.” Economica 81: 522–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12088.

Masters, Robert. 1989. “Study Examines Investors’ Risk-Taking Propensities.” Journal of Financial Planning 2 (3): 151.

McClelland, David C. 1961. The Achieving Society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand.

Monks, James. 2000. “The Returns to Individual and College Characteristics Evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth.” Economics of Education Review 11.

Overton, Rosilyn H. 2008. “Theories of the Financial Planning Profession.” Journal of Personal Finance 7 (1): 13–41.

Ryack, Kenneth N., Michael Kraten, and Aamer Sheikh. 2016. “Incorporating Financial Risk Tolerance Research into The Financial Planning Process.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (10): 54–61.

Ryan, James C., Syed A. Tipu, and Rachid M. Zeffane. 2011. “Need for Achievement and Entrepreneurial Potential: A Study of Young Adults in The UAE.” Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues 4 (3): 153–166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17537981111159948.

Sahm, Claudia R. 2007. “How Much Does Risk Tolerance Change?” Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board 66: 44.

Saif, Haroon A.A., and Usman Ghania. 2020. “Need for Achievement as a Predictor of Entrepreneurial Behavior: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Passion for Founding and Entrepreneurial Interest.” International Review of Management and Marketing 10 (1): 40–53.

Subramaniam, Sowmya, and Madhumita Chakraborty. 2020. “Investor Attention and Cryptocurrency Returns: Evidence from Quantile Causality Approach.” Journal of Behavioral Finance 21 (1): 103–115. https://doi-org.er.lib.k-state.edu/10.1080/15427560.2019.1629587.

Van de Venter, Gerhard, David Michayluk, and Geoff Davey. 2012. “A Longitudinal Study of Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (4): 794–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2012.03.001.

Zeffane, Rachid. 2013. “Need for Achievement, Personality and Entrepreneurial Potential: A Study of Young Adults in the United Arab Emirates.” Journal of Enterprising Culture 21 (1): 75–105. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495813500040.

Zhao, Haidong, and Lini Zhang. 2021. “Financial Literacy or Investment Experience: Which Is More Influential in Cryptocurrency Investment?” International Journal of Bank Marketing 39 (7): 1208–1226.