Journal of Financial Planning: December 2021

Carol Anderson is the founder and vice president of Money Quotient, and a member of the Financial Planning Association.

Deanna L. Sharpe, Ph.D., CFP®, is an associate professor in the personal financial planning department at the University of Missouri–Columbia.

NOTE: Please click the images below for PDF versions.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

The client is clearly central to financial planning. Yet, as the profession developed, relatively little research focused on identifying best practices for fostering productive client relationships. Noting this gap, in 2006, Life Planning Consortium1 members developed and conducted the “Survey of Specific Elements of Communication that Affect Trust and Commitment in the Financial Planning Process.”2 This study was among the first to provide empirical support for the critical role communication plays in effective planner-client relationships in financial planning.

However, in the 15 years that have passed since that research was conducted, several significant economic events and social changes have occurred with broad implications for financial planning engagements. Technological advances have transformed business meeting platforms. A series of economic crises have deeply shaken Americans’ sense of financial security and trust in financial markets. Several recessions and the unexpected economic losses due to COVID-19 have heightened financial anxiety. Within our society, diversity, equity, inclusion, and cultural awareness have become salient issues.

In consideration of these changes, the MQ Research Consortium (MQRC)3 conducted a 2021 study, “Developing and Maintaining Trust and Commitment in a Rapidly Changing Environment,” to (1) evaluate the persistence of findings from the 2006 study, and (2) gain insight into the development of successful client-planner relationships in the context of current demographic, economic, and cultural issues. The main objective of this article is to provide an overview of one segment of the 2021 study—an analysis of the effectiveness of qualitative data gathering designed to learn about clients’ (1) cultural values, (2) personality types and traits, (3) money attitudes and traits, and (4) family history and family values.

Communication Tasks

The word “task” is defined as “a function to be performed, an objective.” Therefore, for the purposes of this study, we consider a “communication task” to be one that requires effective engagement for the purpose of facilitating the financial planning process. In this context, we think of a communication task as the place where the art and science of financial planning meet.

This perspective is especially helpful considering the complexity of our lives, wide-ranging sets of personal circumstances, and differing views and experiences related to cultural, societal, political, and environmental issues. The numbers part of financial planning is not nearly as complex as the individuals making the financial decisions. Tim Maurer, financial planner, educator, and author, frequently reminds his readers that “personal finance is more personal than it is finance.”

“…One of the ways we can make financial decisions simple is to genuinely understand what motivates us. These motivations are too often separated from our financial planning even though they are the foundation.”4

The late Richard Wagner, J.D., CFP®, dedicated his life to defining the role of money in shaping and understanding the human experience. He was the recipient of the P. Kemp Fain, Jr., Award, the Financial Planning Association’s highest honor, and author of Financial Planning 3.0: Our Evolving Relationships with Money. He believed, “At its base, money is merely an exchange medium; at its most complex, it is an ultimate existential challenge.”

“Let’s face it. An individual’s relationship with money is a lifelong dance, a dance taking each of us from the most macro of socio-political realities to those relationships of exceeding intimacy—those with our Selves, our spouses, and our families. Money challenges each of us on different levels from daily function to spiritual complexity.”5

Because financial planning is a highly individualized process, the primary goal for financial planners must be getting to know and understand each client. This is at the heart of fulfilling their fiduciary duty and ensuring that the financial recommendations they make will serve their clients’ best interests.

Research Design

Members of MQRC designed two web-based survey instruments—one for financial planners and one for financial planning clients. To facilitate comparisons to historical data, the current survey replicated several items from the 2006 survey. FPA announced the study to its membership and provided a direct link to the web-based planner survey. Members of other professional organizations were also sent invitations to participate via social media links.

At the conclusion of the electronic survey, planners were asked to help obtain the views of clients by inviting five or more of their clients to participate in this research. The collection of planner and client data took place May 25, 2021, through June 15 and yielded a convenience sample of 352 usable planner surveys and 429 usable client surveys. The response rate for the planner survey was 11.08 percent, a rate comparable to other research that surveyed financial planners.6 Since the planner participants extended the invitation to their clients, the total number of clients who received invitations is unknown.

Variables of Interest

Dependent Variables:

Client Trust and Client Commitment

In the 2006 and the 2021 studies, Cronbach’s alpha7 was used to construct four additive scales: (1) client trust from the clients’ perspective, (2) client trust from the planners’ perspective, (3) client commitment from the clients’ perspective, and (4) client commitment from the planners’ perspective. This strategy followed the approach of previous research conducted by Christensen and DeVaney, and Sharma and Patterson8 (see Appendix).

Independent Variables:

Qualitative Data Gathering

Previous research established that a significant and positive relationship exists between communication and client trust and commitment. However, communication was defined in broad, general terms and was largely focused on exchanging financial information. In contrast, this article focuses on four qualitative data gathering tasks: Planner makes effort to explore and learn about (1) client’s cultural values, (2) client’s personality type and traits, (3) client’s money attitudes and beliefs, and (4) client’s family history and family values.

Summary of Results

Univariate analysis indicated the frequency of client and planner responses. Bivariate analysis (Spearman correlation) evaluated the direction and significance of relationships between the qualitative data gathering tasks and the development of client trust and client commitment. Separate analyses were conducted on planner and client responses. Results of the 2021 and 2006 surveys are compared and differences discussed.

1. Planner Makes Effort to Learn About Cultural Values

Opinions of Planners and Clients (univariate analyses)

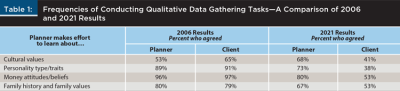

Sixty-eight percent of financial planners reported that, when gathering client data, they make every effort to learn about cultural values. In contrast, 41 percent of client respondents reported that when gathering client data, their planner makes an effort to learn about their cultural values (see Table 1).

Comparison to 2006 results: 53 percent of planners indicated agreement compared to 65 percent of clients.

Statistically Significant Relationships with Client Trust and Commitment (bivariate analyses)

From the perspective of both planners and clients, this finding indicates that a direct and a positive relationship exists between planners who make an effort to learn about a client’s cultural values and higher levels of client trust and client commitment (see Table 2).

Comparison to 2006 results: no planner correlations were statistically significant; client correlation for trust was not statistically significant, but client correlation for commitment was statistically significant.

2. Planner Makes Effort to Learn about Personality Type/Traits

Opinions of Planners and Clients (univariate analyses)

Seventy-three percent of financial planners reported that when gathering client data, they make an effort to learn about their client’s personality type/traits. In contrast, only 38 percent of client respondents reported that when gathering client data, their planner makes an effort to learn about their personality type/traits (see Table 1).

Comparison to 2006 results: 89 percent of planners indicated agreement compared to 91 percent of clients.

Statistically Significant Relationships with Client Trust and Commitment (bivariate analyses)

From the perspective of both planners and clients, the finding indicates that a direct and a positive relationship exists between planners who make an effort to learn about a client’s personality type/traits and higher levels of client trust and client commitment (see Table 2).

Comparison to 2006 results: no planner correlations were statistically significant; client correlations for both trust and commitment were statistically significant.

3. Planner Makes Effort to Learn about Money Attitudes/Beliefs

Opinions of Planners and Clients (univariate analyses)

Eighty percent of financial planners reported that when gathering client data, they make every effort to learn about their client’s attitudes and beliefs about money. In contrast, 53 percent of client respondents reported that when gathering client data, their planner makes an effort to learn about their attitudes and beliefs about money (see Table 1).

Comparison to 2006 results: 96 percent of planners indicated agreement compared to 97 percent of clients.

Statistically Significant Relationships with Client Trust and Commitment (bivariate analyses)

From the perspective of both planners and clients, this finding indicates that a direct and a positive relationship exists between planners who make an effort to learn about a client’s attitudes and beliefs about money and higher levels of client trust and client commitment (see Table 2).

Comparison to 2006 results: no planner correlations were statistically significant; no client correlations were statistically significant.

4. Planner Makes Effort to Learn about Family History and Family Values

Opinions of Planners and Clients (univariate analyses)

Sixty-seven percent of financial planners reported that when gathering client data, they make an effort to learn about their client’s family history and family values. Fewer clients (53 percent) reported that when gathering client data, their planner makes an effort to learn about their family history and family values (see Table 1).

Comparison to 2006 results: 80 percent of planners indicated agreement compared to 79 percent of clients.

Statistically Significant Relationships with Client Trust and Commitment (bivariate analyses)

From the perspective of both planners and clients, this finding indicates that a direct and a positive relationship exists between planners who make an effort to learn about a client’s family history and family values and higher levels of client trust and client commitment (see Table 2).

Comparison to 2006 results: no planner correlations were statistically significant; client correlations were statistically significant with both trust and commitment.

Conclusions

Univariate Analyses

Table 1 provides a 2006 and 2021 comparison of frequencies related to qualitative data gathering practices. In 2021, planners consistently rated themselves much higher than clients did for conducting this type of discovery, a difference that ranged from 15 to 35 percentage points. However, the results were quite different in 2006. For three of the four areas of qualitative data gathering, percentages of agreement were much higher with differences between planner and client responses being just one or two percentage points. The one exception was the cultural values variable, which indicated a more moderate level of agreement and a 12-percentage point difference between planner and client responses.

Bivariate Analyses

Table 2 indicates that both planner and client responses in 2021 demonstrated highly significant correlations between qualitative data gathering tasks and measures of client trust and client commitment. These results are in sharp contrast to those observed in analyses of 2006 data, where none of the correlations with planner responses were statistically significant, and only five of eight possible correlations with client responses were statistically significant.

Recommendations

Considering the strong correlations demonstrated in the 2021 analyses between qualitative data gathering and the development of client trust and commitment, we offer the following recommendations for strengthening your client relationships: (1) listen to understand and (2) nurture cultural awareness.

Listen to Understand

In our work with financial planners and financial planning students, we frequently point out that a successful practice is built on getting to know and understand their clients. We also emphasize that this objective can only be met through exploring each client’s unique frame of reference.

There are many other terms for this concept, such as perspective, world view, and mode of operation. However, the one we like best is “maps” as defined in Communication with Clients: A Guide for Financial Professionals:

“As people grow and develop, they store their life experiences and their reactions to those experiences. A person’s experiences are gradually woven into a personal representation of the world . . . Each person’s package of life experiences is analogous to a fine tapestry . . . In this book we will refer to these finely woven personal representations as maps.”9

—Charles J. Pulvino, James L. Lee, and Cynthia Forman

The authors also emphasize that maps have a powerful influence on an individual’s financial life.

“Clients’ maps affect how they make decisions; how they use money; how willing or capable they are to take risks; and how they view their personal, business, and financial goals. By understanding clients’ maps, you have a better basis for communicating with them.”

In addition, we believe that the key to unlocking each client’s frame of reference is by employing “empathic listening.” The late Stephen Covey called this the most important communication skill and devoted a whole chapter in The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People to explain its nuances and benefits.10

“In empathic listening, you listen with your ears, but also, and more importantly, listen with your eyes and with your heart. You listen for feeling, for meaning. You listen for behavior. You use your right brain as well as your left. You sense, you intuit, you feel. . . . You’re listening to understand.”

Nurture Cultural Awareness

The rise in population diversity increases the importance of recognizing the many ways that culture can influence perspectives, values, and goals in life. The ability to be aware of cultural differences and to adapt professional service to be congruent with a client’s culture is becoming recognized as an important professional competency within service-focused professions.11 In financial planning practice, this rise in population diversity calls for noting ways in which one’s own culture may differ from that of clients, avoiding assumptions about client beliefs and values, and actively seeking to understand a client’s priorities, needs, and goals within the context of the client’s culture.12

Therefore, a financial planner’s investment in knowledge and training in this area will realize both personal and professional benefits. According to the National Center for Cultural Competence at Georgetown University, cultural awareness includes:

- Having a firm grasp of what culture is and what it is not

- Having insight into intracultural variation

- Understanding how people acquire their cultures and culture’s important role in personal identities, life ways, and mental and physical health of individuals and communities

- Being conscious of one’s own culturally shaped values, beliefs, perceptions, and biases

- Observing one’s reactions to people whose cultures differ from one’s own and reflecting upon these responses

- Seeking and participating in meaningful interactions with people of differing cultural backgrounds

Endnotes

- Members of Life Planning Consortium in 2006 included, in alphabetical order: Carol Anderson, president, Money Quotient; Susan Galvan, co-founder and CEO, The Kinder Institute; Deanna L. Sharpe, Ph.D., CFP®, associate professor, personal financial planning, University of Missouri–Columbia; Martin Siesta, CFP®, ChFC, senior financial planner, Compass Wealth Management LLC; and Andrea White, MCC, president, Financial Conversations.

- The Financial Planning Association (FPA) co-sponsored the 2006 research project. The Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, Inc. provided partial funding. Results were published in the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, Journal of Financial Planning, and as an FPA Press white paper. See: Sharpe, Deanna L., Carol Anderson, Andrea White, Susan Galvan, and Martin Siesta. 2007. “Specific Elements of Communication That Affect Trust and Commitment in the Financial Planning Process.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 18 (1): 2–17; Anderson, Carol, and Deanna L. Sharpe. 2008a. “The Efficacy of Life Planning Communication Tasks in Planner-Client Developing Successful Relationships.” Journal of Financial Planning 21 (6): 66–77; Anderson, Carol A., and Deanna L Sharpe. 2008b. “Research: Communication Issues in Life Planning. Defining key Factors in Developing Successful Planner/Client Relationships.” Denver, CO: FPA Press.

- Members of the Money Quotient Research Consortium (MQRC) in 2021 included, in alphabetical order: Thom Allison, CFP®, founder of Allison Spielman Advisors, MQ University faculty member; Carol Anderson, president, MQ Research & Education; Josh Harris, CFP®, AFC, department of finance Clemson University, doctoral student at Kansas State University; Derek R. Lawson, Ph.D., CFP®, assistant professor, personal financial planning, Kansas State University, partner and chief compliance officer, Priority Financial Partners; Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, CFT-I, professor of practice in personal financial planning, director personal financial planning master’s program, personal financial planning, Kansas State University; Deanna L. Sharpe, Ph.D., CFP®, associate professor, personal financial planning department, University of Missouri–Columbia; and David Yeske, Ph.D., CFP®, principal of Yeske Buie, distinguished adjunct professor and director of the financial planning program at Golden Gate University.

- Maurer, Tim. 2016. Simple Money: A No-Nonsense Guide to Personal Finance. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

- Wagner, Richard B. 2016. Financial Planning 3.0: Evolving Our Relationships with Money. United States: Outskirts Press.

- Christiansen, Tim, and Sharon A. DeVaney. 1998. “Antecedents of Trust and Commitment in the Financial Planner-Client Relationship.” Financial Counseling and Planning 9 (2): 1–10.

- Hatcher, Larry, and Edward J. Stepanski. 2001. A Step-By-Step Approach to Using the SAS System for Univariate and Multivariate Statistics. Cary, NC: SAS Institute.

- Christiansen and DeVaney. 1998; Sharma, Neeru and Paul G. Patterson. 2000. “Switching Costs, Alternative Attractiveness and Experience as Moderators of Relationship Commitment in Professional, Consumer Services.” International Journal of Service Industry Management 11 (5): 470–490.

- Pulvino, Charles J., James L. Lee, and Carol A. Pulvino. 2002. Financial Counseling: A Strategic Approach. 2nd ed. Madison, WI: Instructional Enterprises.

- Covey, Stephen R. 1990. The Seven Habits of Highly Successful People. New York: Free Press.

- Wilson, Scott. 2021, April 6. “Understanding Cultural Competency.” HumanServicesEdu.org. www.humanservicesedu.org/cultural-competency/.

- Purnell, Larry. 2005. “The Purnell Model of Cultural Competence.” Journal of Multicultural Nursing and Health 11 (2): 7–14.

- Georgetown University. n.d. “Cultural Awareness.” https://nccc.georgetown.edu/curricula/awareness/index.html.

Appendix A

To assess trust and commitment from both planner and client perspectives, four additive scales were used. To construct the scales, planners and clients were presented with a series of statements related to either trust or commitment and asked to “Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.” Responses included: strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree or disagree, somewhat agree, strongly agree.

Client Trust from the Client’s Perspective

- I have confidence in my financial planner’s integrity.

- I have confidence in my financial skills and expertise.

- I can rely on my financial planner to follow through on their commitments.

- I trust my financial planner.

- I view my financial planner as a sincere person.

Client Trust from the Planner’s Perspective

- My clients have confidence in my integrity.

- My clients have confidence in my financial skills and expertise.

- My clients can rely on me to follow through with my commitments.

- My clients trust me.

- My clients view me as a sincere person.

Client Commitment from the Client’s Perspective

- I am very committed to maintaining a relationship with my financial planner.

- I intend to stay with my financial planner indefinitely.

- I have a strong sense of loyalty toward my financial planner.

- I could be persuaded to transfer to a different financial planner.

- I put maximum effort into maintaining my relationship with my current financial planner.

- My financial planner is my primary financial planner.

Client Commitment from the Planner’s Perspective

- My clients are very committed to maintaining a relationship with me.

- My clients intend to retain me as their financial planner.

- I believe my clients are loyal to me.

- My clients could be persuaded to transfer to a different financial planner.

- I am my clients’ primary financial planner.