Journal of Financial Planning: December 2023

Executive Summary

- Widowed survivors typically pay a higher tax rate, even though their income has declined, because tax brackets for singles may be only half as wide as for married taxpayers filing jointly.

- Cognitive errors catalogued in behavioral finance, such as the availability heuristic, explain why retired couples (and their advisers) can be made to fear the widow tax hit, leading to actions intended to alleviate it.

- This paper attempts to allay that fear and help planners not to overreact to a threat that is more apparent than real.

- For retired couples receiving Social Security and Medicare, the dollar tax hit incurred when the survivor enters the single brackets is likely to be inconsequential.

- Fear of the widow tax hit stems from a myopic focus on tax rates combined with a neglect of the changes in expenditure that must also follow the first passing.

*I want to acknowledge the insights contributed by a Bogleheads forum on this paper, and to thank my colleagues Meir Statman and Hersh Shefrin for their insights into how to approach financial planning in behavioral terms.

Edward F. McQuarrie is professor emeritus at the Leavey School of Business, Santa Clara University. His current research focuses on market history and its implications for financial planning. He can be reached HERE.*

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions

“Nothing is certain but death and taxes.”

—Benjamin Franklin

Does the widow tax hit threaten the well-being of the surviving spouse? The argument runs as follows:

- Although the couple may enjoy a comfortable income, that is because as married filing jointly, their tax rates are low to moderate;

- Unfortunately, the widow will have to pay taxes as a single, where most brackets begin at half the dollar amount for MFJ;

- Causing their tax rate to rise even as their income drops;

- Leading to a significant crimp in lifestyle if something is not done.1

That something might be a Roth conversion, a permanent life insurance policy, a trust, or a relationship with a new financial planner.

So runs the conventional wisdom challenged in this paper.

Literature Review

If the debunking undertaken in this paper is sound, then there should be no academic literature on the widow tax hit. Academic journal reviewers will not be subject to the cognitive errors of ordinary retirees, hence there will be no published papers on the widow tax hit because scholars will not fall into the trap of supposing that there is any material impact. And indeed, no papers were found on scholar.google.com using the phrase “widow tax” in quotes; without quotes, articles on the estate tax and the spousal exemption appeared, with most of these decades old.2

A search of the general web did produce multiple hits. These were typically articles in the financial press, presentations and webinars by practitioners, posts on topical discussion boards, or websites of firms offering financial planning services. Approaches fell into three general groups. In the press and in practitioner presentations, discussions typically took the form of alerts or cautions: that the widowed survivor is going to be taxed as a single, at maybe an unexpectedly high rate, and couples needed to plan for this burden. On discussion boards, fear was the theme, with married couples looking for a way to avert the damage of the expected higher single rate, such as by aggressive Roth conversions. On firm websites, a promotional treatment was typical, with the widow tax hit used as a mild fear appeal to motivate the prospect to retain a financial planner.

The audience for this paper, then, is not the academic reader. It is the planner who may have to assuage fearful clients, and who may benefit from a framework for thinking about how clients’ tax situation will change after widowing and how the survivor’s taxes fit into the larger picture of postmortem planning. The takeaway: avoid a myopic focus on tax rates. Keep the focus on income planning for the widowed survivor.

Requirements for a Tax Penalty

For the widow tax hit to bite, a substantial portion of income must continue after the first death. If instead half the couple’s income were to fall away at the first death, this would match the halving of the tax bracket boundaries for singles and eliminate the tax worry (although not other worries). For instance, the survivor benefit for most federal pensions is capped at 50 percent. If such a pension provides a substantial portion of the couple’s income, then the survivor’s income will fall by almost half, and they are unlikely to be in a higher tax bracket.

Other couples may receive a substantial portion of their income from RMDs, investment income, or other sources whose amount may not decrease at death. However, there will almost always be some reduction in income at the first death, as when both members of the couple had been receiving Social Security. What clients fear is a reduction that nonetheless pushes the survivor into a higher tax bracket, despite that somewhat lower income.

RMDs are a particular threat. If the portfolio has a positive return, the steady increase in the withdrawal rate with age will produce substantially higher income over time, possibly driving the survivor into a still higher marginal tax bracket at later ages (McQuarrie 2022). The RMD threat is also important because it has an apparent solution: Roth conversions while the couple is alive, intended to reduce future RMDs and thus protect the widowed survivor.

To debunk the widow tax hit is also to challenge this justification for Roth conversions. A later section will develop the argument.

Behavioral Finance Perspective

Many believe the widow tax hit presents a real threat. Since this paper will argue that it is nothing to fear, it is important to explain how this mistaken idea could have taken root. The behavioral finance literature provides insight.3 It teaches that decision-makers are prone to misleading heuristics—rules of thumb that do not always apply to the situation at hand. One prominent instance is the availability heuristic: the tendency of decision-makers to focus on information that is readily available, to the exclusion of the nuance and detail that distinguish one situation from another.

In the case of the widow tax, the most available information is the halving of the tax bracket levels for the survivor. The erroneous inference that follows: the widow/er will now be paying twice the amount of tax, or paying twice as high a tax rate, or must face some burden that is twice as high, causing them to live only half as well. Unless something is done.

This heuristic ignores the detail that tax payments under a progressive tax system are computed as a weighted sum:

Dollar tax obligation = å Bj × Txi + $n × Txlast

where each Bj is the dollar span of a bracket completely filled, Txi are the corresponding tax rates applicable to the filled brackets, $n is the dollar amount of income that falls into the highest bracket entered, and Txlast is the marginal rate in that bracket.

The mathematical styling highlights what is not the case mathematically: successive tax rates do not increment by a constant, and brackets are not equal in dollar span. Only if these absent constraints were satisfied, and only for some increment series and some bracket span ratios, would the widow/er be likely to pay about twice as much tax on the same income.

That is the nuance and detail that gets lost when relying on the highly available information that single tax brackets are cut in half. Once the details of tax calculation under the current tax structure have been grasped, it becomes apparent that there can be no simple answer to the question of whether the widowed single will pay a little bit more, a moderate amount more, or a lot more in tax dollars for any dollar reduction in income.

Intuition is further stymied by the question of exactly how much the survivor’s income will drop when the spouse’s Social Security payment or other life-only income drops away. This reduction will come out of the single’s marginal tax bracket, reducing tax at the marginal rate, which may be quite a bit higher than their average rate.

Next, there must also be some reduction in expenditure when the first spouse dies. No affluent retiree eats only air, drinks only tap water, or walks everywhere in a robe barefoot without ever needing medical care. On the other hand, expenditures are unlikely to fall by anywhere close to half—housing is a good example of a fixed cost that may not decrease by even a dollar simply because one spouse has passed away.

Intuition inclines toward some increase in tax payment for the widow/er taxed as a single. But there must also be some decrease in expenditure. At a minimum, Medicare and other health insurance payments need no longer be made for the deceased spouse. How these factors net out is likewise not easily discernible.

Behavioral finance encourages attention to framing. Most invocations of the widow tax hit keep the increase in tax rate paid by the widow/er at the center of the frame. But regardless of what happens to taxes paid, there must also be a reduction in expenditure when one spouse passes away. Keeping both outcomes within the frame of view is key to debunking the threat.

The Tax Hit for Affluent Couples

This section presents illustrative cases. It will show that when the problem is reframed in terms of dollars rather than rates, the widow tax hit becomes less of a concern. A second reframing in terms of dollars of income available for living expenses, rather than dollars of tax paid, will further defang it.

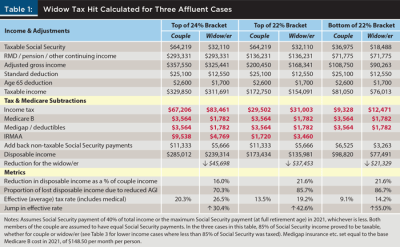

Table 1 computes the tax hit and the reduction in disposable income for the widow/er for three cases: (1) when the couple’s retirement income had placed them at the top of the 24 percent bracket (~$350,000 AGI); (2) the bottom of the 24 percent bracket / top of the 22 percent bracket (~$200,000); and (3) the bottom of the 22 percent bracket (~$100,000). These values were selected to focus on the mass affluent client. Higher and lower income levels will be examined later. The middle columns—pertaining to income near the 22 percent / 24 percent bracket boundary—present the most interesting case and will be discussed first.

As can be seen in Table 1, even though the survivor’s AGI drops by over $30,000, their income tax payments go up, just as feared. Furthermore, whereas the couple had only been in the first IRMAA bracket, the single survivor has to pay the first three IRMAAs, so the IRMAA dollars also increase even though only one person now pays IRMAA. And, jumping to the bottom of the table, the effective tax rate goes up by over 40 percent, relative to what the couple had paid.

But none of these adverse changes amounts to much in dollar terms. So long as the deceased spouse consumed at least 21 percent, or one-fifth, of the disposable income they had enjoyed as a couple, in the form of consumption that stops at death, the survivor will be just as well off as before (financially speaking). The widowed single does pay more in income tax than the couple had, but the increment is tiny: less than 1 percent of the couple’s AGI. The single does pay more in IRMAA than the couple in the middle case, but the increment is again less than 1 percent of the couple’s AGI. Tax effects are swamped by the loss of the spouse’s Social Security payment; but since this was somewhat less than 20 percent of total income in the middle column, that loss is survivable if expenses fall by only a little more.

The left and right portions of Table 1 show that results for the middle case are robust within the income range covered by the table. The widow/er always pays more in income tax than the couple—over $15,000 more at the top end—but the increment is never material by the metric of sustaining an adequate disposable income, defined as at least 75 percent of the disposable income the couple had. The survivor’s effective tax rate is always substantially higher, but again, it does not matter, because the effective tax rate for the couple, in this income range, had not been very high. The big percentage increase in effective tax rate only translates into some thousands of dollars of extra tax payments for the survivor, even as these couples had enjoyed income in the low six figures.

For couples with retirement income between $100,000 and $350,000, it is a mistake to fear the hit from the widow tax. On the other hand, lost income is always to be feared. Had more than 20 percent of income disappeared at death, disposable income for the surviving spouse might have been reduced by a dangerous amount. But the problem would be the income loss—not the tax hit.

The widow tax hit emerges from Table 1 as a classic instance of the kind of misleading heuristic identified and checked by an awareness of behavioral finance. The potential tax costs are so salient that these obscure the reduction in expenditure that must also occur. Table 1 shows that the widow/er does pay more dollars in tax and does pay at a higher rate; but Table 1 also shows that when these are viewed in context, the impact on the survivor’s ability to sustain their prior lifestyle is likely to be minor.

Why Doesn’t the Widow/er Pay Twice as Much Tax?

This section unpacks the numerical results in Table 1. The following section then tests whether the widow tax hit can be made to reappear—if the couple’s income were made to be low enough, i.e., pressed further down in the tax structure.

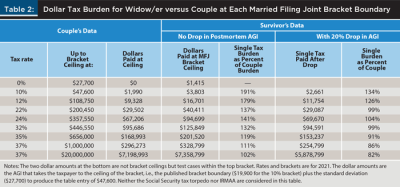

Table 2 calibrates the tax burden borne by the single survivor relative to the tax burden on a couple for the case where either no reduction in income or a 20 percent reduction occurs. The breakpoints are at the ceiling of each MFJ bracket. The five leftmost columns will be discussed first. At the top of the lowest MFJ bracket, defined by the standard deductions, the couple pays zero and the widow/er pays $1,415—a clear case of a tax hit, and clearly attributable to the smaller standard deduction, i.e., having fewer dollars taxed at 0 percent.

Next, at the top of the lowest rate bracket for couples (10 percent), the widow/er pays $3,803, almost double the couple, and again, a notable tax hit. But then the pattern begins to change. In the middle and higher brackets for the couple, the survivor’s income may be split between the same or the next higher bracket, and the tax burden does not rise as fast as when the widow/er had reached the 12 percent bracket while the couple had not yet climbed out of the 0 percent bracket. Likewise, the widowed single will reach the highest bracket sooner than the couple, but once both are in the top bracket (37 percent), the tax burden for each will rise at the same rate. As income rises into the millions of dollars, the magnitude of the survivor’s tax burden necessarily begins to converge with that of the couple’s, reducing any tax hit to a smaller and smaller proportion of income.

Recall that some reduction in income on the first death is almost inevitable. At least, Social Security payments will drop by 33 percent to 50 percent. When both spouses have equal benefits, and when Social Security is 40 percent of total retirement income, income drops by 20 percent after death. Accordingly, the rightmost columns of Table 2 are intended to clarify what happens when AGI is reduced by exactly 20 percent at all breakpoints.4

As mentioned earlier, any income reduction will cut into the tax dollars owed by the widow/er at their marginal rate. To capture that effect, the rightmost column of Table 2 re-expresses the survivor’s tax burden as a percentage of the couple’s tax. At low income levels there is still an incremental burden on the widow/er—they have lost 20 percent of income and nonetheless faces a dollar tax burden one-quarter to one-third greater than the couple. But as soon as the couple’s income passes $100,000 or so, the survivor’s tax excess shrinks rapidly until it disappears in the vicinity of couple income of $200,000. In fact, once the couple’s income reaches the higher tax brackets, a bit under $500,000, the widow/er will begin to pay less tax than the couple, in part because the single brackets cease to be exactly half the MFJ brackets by this point.

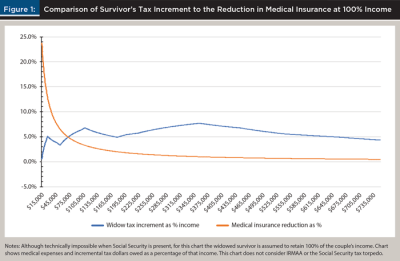

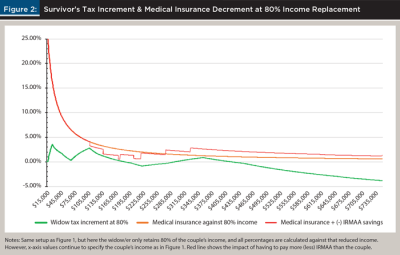

Table 2 used discrete cut points per the tax bracket structure. Figures 1 and 2 attempt a more continuous description. In Figure 1, the blue line represents the excess tax paid by the widow/er. It charts the pure effect of being taxed as a single rather than MFJ on the exact same income. The orange line represents the necessary reduction in medical insurance expense that occurs when a single person replaces a couple, also expressed as a percentage of income. So long as the orange line is above the blue line, there cannot be a widow tax hit, because the reduction in medical insurance costs exceeds the dollar increment in tax paid.

Note how the blue tax line in Figure 1 zigs and zags, as the widow/er moves through tax brackets at a different pace than the couple. Accordingly, the widow tax hit, expressed as a percentage of income, does not increase or decrease smoothly. Next, reading from the right side, the orange line does not cross over the blue line until AGI declines below about $75,000. Absent a Social Security tax torpedo, as investigated in the next section, or other factor extraneous to the income tax structure, there cannot be a widow tax hit at lower income levels. Figure 1 shows how variable the widow tax hit can be—when there is zero reduction in income after the first death.

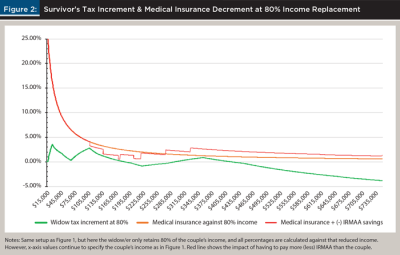

Figure 2 extends the analysis, parallel to the right columns in Table 2, by giving the widow/er an income of exactly 80 percent of what the couple had. Here the green line represents the excess tax paid by the widow/er, if any, when their income drops by 20 percent after death, relative to the tax paid by the couple on 100 percent of their income; the line charts this excess tax as a percentage of the survivor’s reduced income. That green line, which is quite a bit lower than the blue line in Figure 1, captures the tax savings that result when reduced income after death reduces tax dollars paid at the survivor’s marginal rate. The orange line again is the reduction in medical insurance, now expressed as a percentage of their reduced income, coming in a bit higher than Figure 1. The red line captures the effect of IRMAA, to be discussed last.

In Figure 2, there is no crossover point: the savings in medical insurance always exceed the incremental tax hit. And in fact, consistent with the lower rows in Table 2, past a certain point there is no longer excess tax paid by the widow/er. If the survivor is affluent enough, they get a tax kiss rather than a hit. More generally, reducing tax at the marginal rate is so powerful that the widow tax hit melts away once the couple’s income reaches the 35 percent bracket or higher.

As a final check, the red line in Figure 2 adds the savings or the debit from IRMAA to the orange line that shows savings from medical insurance per se. Recall from Table 1 that, depending on the exact level of income, a widow/er might either save IRMAA, parallel to how they save on Medicare B, or instead pay extra in IRMAA. Figure 2 shows just how complicated the IRMAA effect can be. In part because of its cliff edge nature, the with-IRMAA expenditure reduction line zigs and zags more sharply and also more often. Fortunately, the red line remains above the green line at all points. But were the widow/er to retain somewhat more of the couple’s income, say 85 percent or 90 percent, IRMAA would drive a real, albeit small, tax hit within a narrow range at very specific income levels (Reichenstein and Meyer 2020).

Stepping back, it appears that if there is to be a material widow tax hit, it must occur at relatively low income levels, and given the chart in Figure 1, perhaps only when the Social Security tax torpedo applies.5

Does a Widow Tax Reappear at Lower Incomes?

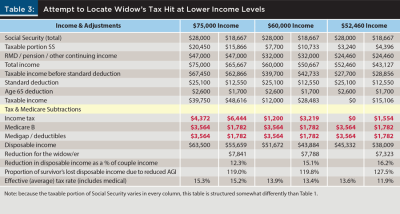

Table 3 examines three income scenarios, all falling within the 12 percent or 10 percent bracket for couples (after all deductions and exclusions), corresponding to total income of $75,000, $60,000, and $52,460. The latter value is the point where the couple’s taxable income, after exclusion of a portion of Social Security payments, equals zero, i.e., falls within the standard deductions. Next, in these lower income scenarios, Social Security payments for the couple are set equal to the 2021 average Social Security payment, plus 50 percent for a non-working or lower income spouse. On death, the widow/er steps up to that full average payment while giving up their own, which causes their total Social Security payment to fall by one-third relative to the couple’s.

Proceeding from left to right in Table 3, an income of $75,000 for the couple causes the average Social Security payment plus 50 percent to equal 40 percent of total couple income, for a tight parallel with the cases in Table 1. Here the couple is still progressing through the Social Security tax torpedo, while the widow/er has got all the way through it, meaning a greater portion of their Social Security is subject to tax (85 percent). Accordingly, their taxable income is higher than the couple’s, even though about $9,000 of Social Security payments stopped with death. Hence, the survivor pays over $2,000 more in income tax. But it does not matter; the reduction in medical insurance payments overwhelms the increased tax, and disposable income is almost 88 percent of what the couple enjoyed.

At an income of $60,000, both the couple and single are located within the Social Security tax torpedo; but the widow/er is so far into it that their taxable income is almost 2.5 times that of the couple, making their tax about $2,000 greater. But the survivor still loses no more than 16 percent of the couple’s disposable income, net of tax increases and medical insurance reductions.

At an initial income of $52,460, both the couple and single are well down in the Social Security tax torpedo, so that taxable income is much less than total income. The widow/er again pays more in tax, but their disposable income still falls by not much more than 16 percent. But the problem is not the tax hit, which is less than the money saved on Medicare B alone—the problem is the loss of income, consequent to reduced Social Security payments.

In sum, even at these modest income levels, it was not possible to locate a combination of circumstances where the widow tax hit was material. The postmortem decrease in medical insurance payments under the assumptions used was almost $3,500; the increase in tax payments topped out below $2,500 in these lower income levels; accordingly, there can be no widow tax hit anywhere in this range.

The Mirage of Tax Planning

The widow tax hit is a staple among pitches for Roth conversions. In this section, conversions will serve as a stand-in for a broader class of tax planning measures, all of which are intended to reduce taxable income while the couple is alive, in this case RMDs, to ensure that the widow/er will face less of a tax hit once single tax rates apply. This section will show that all such tax planning measures suffer from a fatal contradiction.

Suppose, similar to the middle case in Table 1, a couple was on track for $200,000 of income, including $120,000 of fully taxable RMDs from a traditional 401(k). For the sake of discussion, assume these RMDs have recently begun, meaning the couple is about age 73 or a little more. Let that be the counterfactual if no tax planning had been done; in which case, the widow tax hit will be approximately the same as in Table 1, i.e., not terribly problematic.

Alternatively, suppose that some years before, working with a financial planner, the couple had made Roth conversions amounting to a few hundreds of thousands of dollars. Assume that by their early 70s that Roth account would have grown to somewhat more than $500,000. The conversion will therefore reduce taxable RMDs by about $20,000 ( = $500,000 divided by early year RMD divisors, which are 25 +/-),6 relative to not having done any Roth conversions. With that reduction in RMDs, taxable income for the couple will now be only $180,000. In other words, the conversion will have done its job of reducing taxable income by reducing the balance subject to RMDs (McQuarrie and DiLellio 2023).

Will the couple begin to draw down the Roth accounts at age 73, taking out, say, $15,000 a year, to restore the disposable income they would have had from the $20,000 of averted taxable RMDs? Unlikely. Part of the pitch for Roth accounts is that they do not have RMDs. The second part of the pitch: Roth accounts can be left to compound tax-free for a long time, and then passed on to heirs tax-free. If the converted amounts prove to be truly surplus, then the Roth can be left untouched, absent an emergency need, and a much larger after-tax bequest can be left to heirs, 20, 30, or 40 years later, relative to not having done the conversion (Young 2020).

Accordingly, the $20,000 of taxable income that the Roth conversion averted by reducing RMDs, and the ~$15,000 of disposable income not drawn from the Roth, must also be surplus. The couple did not require that money to fund their preferred lifestyle—that is why they can leave the Roth funds undisturbed to accumulate. This means the widow/er does not need to top up their income by that amount to fund the same lifestyle as they had before their partner passed away.

Hence the catch-22: if the tax planning is effective in reducing taxable income while both are alive and the couple’s lifestyle is not diminished thereby, then the averted after-tax income was income that the widow/er also does not need to replace to maintain their lifestyle. Thus, the tax planning was pointless from the standpoint of survivor protection. If the survivor does need that income, then the couple probably did too, and they could not have afforded the cost of the tax planning (e.g., the reduction in income produced by the untapped Roth conversion and the loss of wealth from prepaying tax to enable the conversion). Catch-22: tax planning is pointless if affordable, unaffordable if on point. There are many good reasons to make a Roth conversion, but widow protection is not on the list.

Behavioral finance again provides perspective on why some clients might suppose that a Roth conversion could provide valuable assistance to the widowed survivor. Roth conversions are most successful when the tax rate at conversion is lower than the tax rate expected to apply to RMDs in the absence of a conversion (Horan, Peterson, and McLeod 1997; Reichenstein 2020). Spreadsheets can be devised to show that the dollar payoff rises in line with the percentage point difference between the tax rate at conversion and the tax rate in retirement (McQuarrie and DiLellio 2023). Any such spreadsheet can be made to show much more favorable conversion outcomes, if one member of the couple is made to die early in retirement even as the survivor stays alive for decades to come. The higher single tax rate gets entered at the first demise and conversion outcomes improve, perhaps dramatically, in line with the difference in tax rate.

Behavioral finance helps planners and their clients not to confuse prospective and retrospective judgments. In retrospect, a Roth conversion will be accounted more successful if one member of the couple dies very soon after RMDs begin, so that the high single tax rate can be applied throughout in figuring the conversion payoff. But that retrospective accounting cannot be an argument for doing a Roth conversion in the first place. If married clients are on the fence about converting, a planner can certainly rerun the Roth spreadsheet with the older spouse dying several years before their life expectancy and the younger living several years past their life expectancy and calculate the improvement in dollar outcomes relative to the couple both surviving to joint life expectancy. But if the planner is going to engage in that kind of hypothetical, they should also run a spreadsheet where each spouse incurs substantial medical expenses in the several years before they pass at life expectancy—expenses that would have been deductible if taken from a non-converted traditional IRA—and then re-examine the Roth payoff under those circumstances as well.

Roth conversions are a wager on longevity and future tax rates. If the wager makes sense for the couple, the widow/er will be fine too. But the prospect of widowing cannot be used to justify the conversion unless weighed against the no-less-likely prospect of late-in-life medical expenses that would have been deductible in the absence of a conversion. Prospective judgments are always uncertain.

Conclusion

The numerical illustrations presented in this paper are so straightforward and the generality of results across typical middle-income levels so easy to establish that the question must arise: how did fear of the widow tax hit ever take root? Several behavioral explanations have been offered. All pinpoint the problem in a myopic focus on tax rates to the exclusion of a sounder analysis that keeps both tax dollars paid and the postmortem dollar reduction in expenditure at the center of the frame.

Implications for Planners

Planners who advise retired couples will, sooner or later, have to advise a widowed survivor. And for every widowing event, there will be yet other couples wondering how best to prepare for the inevitable. Some of these clients will have heard about the widow tax hit. The planner should be prepared for questions that range from mild curiosity to outright dread. In the latter case, there may be demands for action. What can we do to reduce the tax hit faced by the survivor? Do we need to start Roth conversions?

This paper arms the planner with tools to cool that rush to action. It also inoculates the planner against a hasty judgment in favor of a Roth conversion that won’t pencil out unless the first death occurs relatively soon.

The most important takeaway is to keep the focus on income planning and to steer the client away from an obsessive focus on tax rates. The tables in the paper show how to construct a dollar-based rather than rate-based account of the widowed survivor’s situation. Most clients will not be able to assemble such an account on their own. The tables can help the planner drive home the point that the key fact is not the marginal tax rate paid by the survivor, but the amount of the decrease in disposable income, net of increased taxes and decreased expenditure. That is the number that may (or may not) require action.

Each member of the couple can be invited to build up a budget showing their own expenses as a survivor. Current housing costs won’t change by a dollar. Survivor medical insurance costs won’t change. Food and other necessities will fall, but probably not by half. Entertainment and discretionary expenses will fall, but possibly by different amounts for each individual as when one spouse has an expensive hobby the other does not share. Maintenance expenses may increase if the deceased spouse handled these chores while the survivor will instead have to pay for the service.

When each survivor’s budget is built, it can be compared to the disposable income as calculated in the model tables. If disposable income appears adequate, the clients will be reassured. If not, then the real work of the planner begins. Will housing arrangements have to change? Can more income be found? Far better for these contingencies to be discussed well in advance rather than after the inevitable occurs.

In conclusion, planner and client do better to focus on dollars of disposable income rather than the tax rate paid.

Citation

McQuarrie, Edward F. 2023. “Widow Tax Hit Debunked.” Journal of Financial Planning 36 (12): 62–74.

Endnotes

- Regarding gender: the typical sales pitch uses ‘widow’ and so do I, here at the outset, and when-ever naming the phenomenon, as in the title. The numbers generated for the tables and figures are free of gender and apply regardless of whether the decedent (survivor) is male or female. Hence, outside of a naming context for the most part, I will refer to widow/er, widowed survivor, or just survivor.

- There were also references to a brief legislative glitch that affected some military spouses, not otherwise considered in this paper.

- I will mostly be drawing on the foundational work by Kahneman and Tversky as summarized in Shefrin and Statman (2003). For a more recent perspective on how behavioral finance has evolved since its beginnings, see Statman (2019).

- Although Table 1 set out to reduce “income” by 20 percent by cutting Social Security by half, a combination of the partially non-taxable nature of Social Security, along with bumping up against the current maximum Social Security payment, prevented that 50 percent reduction in Social Security from translating through to an exact 20 percent reduction in AGI at the higher income levels in Table 1, causing the treatment in the two tables to diverge.

- The tax torpedo refers to stretches of income where the marginal tax rate is higher than the statutory income tax rate because each dollar of additional income is taxed itself and responsible for causing an additional 50 cents or 85 cents of the Social Security payment to be taxed. See Reichenstein and Meyer (2020).

- The SECURE Act and the SECURE 2.0 Act changed the required beginning date but not the RMD schedule, where the divisors for ages 73–75 are currently 26.5, 25.5, and 24.6.

References

Horan, S. M., J. H. Peterson, and R. McLeod. 1997. “An Analysis of Nondeductible IRA Contributions and Roth IRA Conversions.” Financial Services Review 6 (4): 243–256.

McQuarrie, E. F. 2022. “Will Required Minimum Distributions Exhaust My Savings and Leave Me in Penury?” SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4001986.

McQuarrie, E. F., and J. A. DiLellio. 2023. “The Arithmetic of Roth Conversions.” Journal of Financial Planning 36 (5).

Reichenstein, W. 2020. “Saving in Roth Accounts and Making Roth Conversions before Retirement in Today’s Low Tax Rates.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (7): 40–3.

Reichenstein, W., and W. Meyer. 2020. “Using Roth Conversions to Add Value to Higher-Income Retirees’ Financial Portfolios.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (2): 46–55.

Shefrin, H., and M. Statman. 2003. “The Contributions of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.” Journal of Behavioral Finance 4 (2): 54–58.

Statman, M., 2019. Behavioral Finance: The Second Generation. CFA Institute Research Foundation.

Young, R. 2020. “The Roth/Pretax Decision in Late Career Years: The Increasing Importance of Accumulated Assets in Light of the SECURE Act.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (7): 59–68.

Read Next

“Minimizing the Damage of the Tax Torpedo,” William Reichenstein, September 2021