Journal of Financial Planning: February 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- Client engagement in financial planning can be enhanced by integrating cognitive and behavioral theories, specifically Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development, Valsiner’s zone theory, and Veilleux’s theory of momentary distress, to focus on client knowledge and willingness to implement recommendations.

- The initiative pathway model (IPM) is developed to classify clients into four zones based on their understanding and readiness to implement financial recommendations, providing a framework to identify when financial therapists should be involved to address biases, anxieties, or trauma. Addressing both client knowledge and willingness has the potential to significantly improve the implementation of financial plans, leading to improved financial well-being and more effective financial planning outcomes.

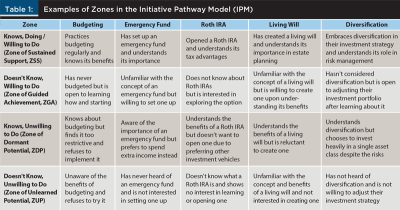

- The four zones identified in the IPM are the zone of sustained support (clients who are knowledgeable and willing), the zone of guided achievement (clients who are willing but lack knowledge), the zone of dormant potential (clients who are knowledgeable but unwilling), and the zone of unlearned potential (clients who are neither knowledgeable nor willing).

- Necessary actions in each zone vary. In the zone of sustained support, clients receive encouragement and reinforcement; in the zone of guided achievement, clients are educated and guided; in the zone of dormant potential, clients’ underlying issues are explored and addressed; and in the zone of unlearned potential, clients are educated and their resistance is managed.

- Adopting the IPM results in a more holistic approach to financial planning by strengthening the planner–client relationship, increasing trust, and promoting collaboration between financial planners and financial therapists.

Oliver Schnusenberg, Ph.D., CFP®, CFT, BFA, is an Earle C. Traynham professor of finance at the University of North Florida. He is a CFP® and CFT professional and a Behavioral Financial Advisor (BFA). Oliver served as the director of UNF’s CFP Board-registered financial planning program from 2016 to 2019. He is also a certified life coach.

NOTE: Click on images below for PDF versions.

Although almost a third of U.S. households utilize the services of financial planners, financial planning clients often struggle with implementing advice from their financial planner or financial therapist, and the implementation of advice is contingent on how the advice is delivered (Chaffin 2015; Somers 2018; White and Heckman 2016). Moreover, existing data sets make measuring best practices or determining if advice is being implemented challenging (Dew, Dean, Duncan, and Britt-Lutter 2020; Dew and Xiao 2011). The lack of implementation may be because clients are unaware, due to a lack of communication, how the action they are being asked to perform or the tool they are being asked to use is beneficial and are therefore unwilling to perform the action or use the tool (Chaffin 2015). Clients may not be ready for change and are resistant, perhaps because they are not emotionally prepared (Klontz, Horwitz, and Klontz 2015; Lerman and Bell 2006). A financial educator or planner must provide the client with skills, knowledge, and the necessary behavior change so that the client is willing to implement the recommendations. Thus, both client knowledge and willingness (attitudes and behaviors) play a significant role in aligning clients’ financial plans with their goals and ultimately achieving financial well-being (Cude 2022; Haupt 2022; Lyons and Kass-Hana 2022).

When considering whether clients have the requisite knowledge and are willing to implement planner recommendations, they can implement them either by themselves or with the planner’s help if they lack the necessary knowledge or skills. It also has to be assumed that the planner’s recommendations are within the allowable legal and regulatory framework. Previous research (Vygotsky 1978; Valsiner 1997) has identified three zones of learning that can be adapted in the financial planning context to consider a person’s ability to act with help from a skilled partner (the financial planner) and the actions or tools that are allowable in the environment (the laws and financial regulations) to implement the recommendations made by the planner. In other words, before implementing recommendations is possible, these zones all have to intersect. Only then does consideration of the client’s willingness to implement the recommendations become relevant. In turn, willingness can only be meaningful if the client knows how the recommendation can be helpful to them. These zones are discussed next.

Theoretical Background—Vygotsky and Valsiner

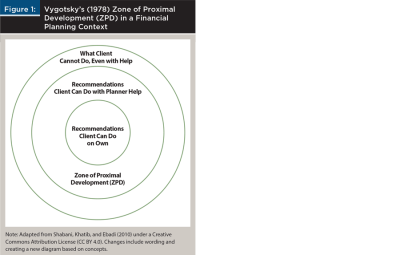

In Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development, the “zone of proximal development” represents the zone in which tasks are beyond a learner’s current abilities but items they can achieve with help, guidance, and encouragement from a skilled partner. In this context, “proximal” refers to abilities the learner can accomplish with help. Learning in this area is the most effective since it is when being able to complete the task is just beyond the learner’s ability. Another essential aspect of Vygotsky’s theory is the notion of “scaffolding,” which refers to the skilled partner breaking down (scaffolding) the material in smaller chunks. Hence, they are more easily digestible by the learner (Wood, Bruner, and Ross 1976). Figure 1 illustrates Vygotsky’s theory. Vygotsky’s theory has been highly influential in educational psychology settings (Esteban-Guitart 2018). It has been applied, for example, to the flipped classroom (Erbil 2020) and in teaching fields such as language acquisition and mathematics (Shabani, Khatib, Ebadi 2010). Vygotsky’s theory, particularly scaffolding, has recently been effectively applied to a financial planning context, emphasizing advisers’ need to educate financial planning clients, particularly concerning multiple-option solutions (Sterbenz et al. 2021), illustrating the importance of communicating knowledge to the client.

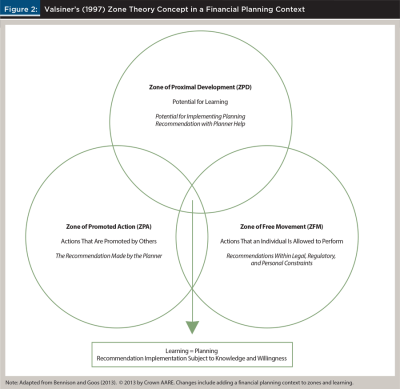

Valsiner (1998) extended Vygotsky’s model by incorporating two additional zones that incorporate environmental constraints (zone of free movement or ZFM) and how other people in the environment promote the individual’s actions (zone of promoted action or ZPA). The ZFM considers access to and availability of objects in the environment and how the learner can interact with the objects. The ZPA includes activities, objects, or areas in the environment where the learner’s actions are being promoted. Interestingly, the ZPA can consist of items currently not in the ZFM and may seem forbidden or inaccessible at the time. Therefore, the ZFM/ZPA is constantly being reorganized. The three zones are interdependent in that they consider what the learner can learn with help from a skilled partner (ZPD) in the context of the constraints placed on the learner by their environment (ZFM) and the actions the learner is being asked to accomplish or tools they are encouraged to use by the skilled partner (ZPA). Valsiner’s zone theory has also been studied in several contexts (Bennison 2022). Figure 2 is an illustration of Valsiner’s zone theory.

Application to a Financial Planning Context

Vygostky’s and Valsiner’s theories can be extended to a financial planning context. In this context, the client is the learner, and the financial planner, financial therapist, or financial coach is the skilled partner. This article refers to this person as the skilled financial partner (SFP). In Figure 1, the language applied to a financial planning context is italicized. Thus, the actions the learner can do independently are the recommendations the client can implement independently. Likewise, the actions the learner can do if guided (i.e., actions in the ZPD) are the recommendations the client can implement with the planner’s assistance.

In a financial planning context, Valsiner’s three zones, ZPD, ZFM, and ZPA, are essential for planning recommendation implementation. Here, the ZPD includes planner recommendations that the client can implement with the help of the SFP or on their own after the SFP explains the recommendation. For example, a client may construct a 60/40 equity / fixed income portfolio by asking the SFP to implement it. As another example, the client seeks to implement a living will but needs the SFP to help them set it up. The ZFM includes all the recommendations that the client can perform (or have performed for them) within the legal and regulatory constraints existing at the time and within the boundaries of external variables, such as laws and regulations, and personal variables, such as tax consequences, estate planning, insurance planning, and others. The ZFM can and will change over time, and planner recommendations will change as the zone changes. Thus, for example, a 50-year-old client may not be able to withdraw funds from their 401(k) penalty-free, but they will be able to do so at age 59½.1 As another example, a client may fall outside the income limits to obtain a full deduction on their traditional IRA contribution. However, their income may decrease in five years as they change careers. Lastly, in a financial planning context, the ZPA includes the recommendations the SFP asks the client to implement to accomplish their financial goals (i.e., the planner recommendations). The SFP may ask the client to utilize a 529 plan for their children’s education, a specific investment vehicle to accomplish their retirement goal, an annuity during retirement, or a particular type of life insurance. Alternatively, the SFP may ask the client to perform a specific action, such as making regular contributions or simply changing their automatic deductions. The ZPA can thus also include financial instruments necessary to implement the recommendation.

All three zones are, therefore, important in a financial planning context. The recommendation the client should implement (ZPA) has to be allowable given the client’s personal as well as legal and regulatory constraints (ZFM), and it has to be within the capability of the client to implement the recommendation with the help of the SFP or on their own after they understand the recommendation (ZPD). At the intersection of these three zones, the financial planning client optimizes their financial goal attainment and well-being by implementing the planner’s recommendation within the allowable personal, legal, and regulatory framework and within their capabilities or with the SFP’s assistance. That is the area in Figure 2 where “learning” takes place, although learning is here defined as financial goal or financial well-being achievement resulting from implementing planner recommendations.

Considering Willingness and Knowledge

Unfortunately, clients often do not implement planner recommendations (Klontz, Horwitz, and Klontz 2015). The best recommendation is useless if it is not utilized by the client (Somers 2018). The resulting question is, therefore, what is missing from the model? After all, it makes perfect sense, is applicable, and explains well what the client should do, albeit with the SFP’s assistance, in the context of their constraints. However, the model does not suggest anything about the client’s willingness to act or their knowledge of how the planner’s recommendation benefits them.

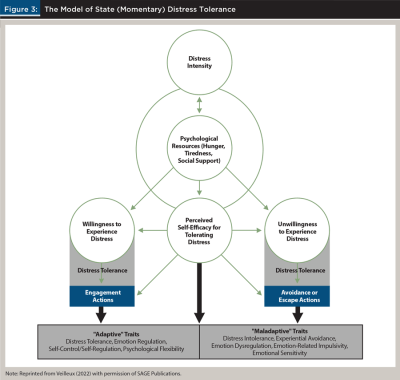

The willingness of the client to implement a planner’s recommendation can be considered in the context of the distress caused by implementation. Veilleux (2022) introduced the theory of momentary distress tolerance, which incorporates action and willingness to accept the distress associated with such an action. Clients choose to engage in action and accept the accompanying distress (i.e., they tolerate it) with the help of adaptive traits, or they avoid the consequences and try to escape the action because of maladaptive traits. In this model, the self-efficacy for tolerating distress is a central predictor for such tolerance and is, in turn, influenced by distress intensity and momentary psychological resources such as social support and the degree of life stressors.

Figure 3 illustrates the theory of momentary distress. While a highly informative model in the context of taking action and tolerating distress, it is unclear what “distress” means. In a separate study, Lass, Veilleux, DeShong, and Winer (2023) tried to identify the word’s meaning to a large group of students. It turns out that there is wide variation in the interpretation of the word, but the most common interpretation of distress is stress and anxiety. Conway, Naragon-Gainey, and Harris (2021) also support the notion that distress tolerance is hard to define specifically and cannot be statistically separated from the neighboring area of emotional health. Consequently, the willingness to perform a promoted action is linked directly to the ability to tolerate distress, which in turn is closely aligned with emotional health, stress, and anxiety. This relationship between financial distress and emotional and behavioral aspects has also been demonstrated in a financial therapy setting (Ross and Coambs 2018).

Veilleux’s theory, therefore, provides an elegant way to combine Valsiner’s ZFM and the ZPA and Vygotsky’s ZPD by considering the tolerance the financial planning client has toward the distress that a planner recommendation evokes, whether that distress originated through past or present events. This theory is an important contributor to the initiative pathway model (IPM) because it directly influences the classification of clients into the four zones. By incorporating Veilleux’s insights on distress tolerance and self-efficacy, the IPM can better identify the specific reasons behind a client’s resistance to implementing financial recommendations. This allows for targeted interventions by financial planners and therapists to address any emotional and psychological barriers, which can ensure more effective financial planning outcomes. Possible learning in the interaction of the three zones may not occur if the recommendation does not happen because of a lack of tolerance to the distress the action causes, dependent on the client’s level of self-efficacy. Indeed, financial self-efficacy is significant in explaining financial anxiety (Lee, Rabbani, and Heo 2023) and financial anxiety impacts financial satisfaction (Lee, Kelley, and Lee 2023). While that distress may be tied to momentary stressors such as current life stressors or social support, it may also be the result of previous life events that caused trauma and/or financial anxieties, which currently affect the client’s emotional health. For example, childhood trauma can have a significant effect on financial behaviors (Ross, Johnson, and Coambs 2022).

While Veilleux’s theory adds a lot of value, the potential distress a planning recommendation may cause the client is not the only relevant factor that may keep them from performing a promoted action. An additional factor important in financial planning is the degree of the client’s knowledge that the planning recommendation would be beneficial and the purpose of the recommendation (Bartholomae, Kiss, and Pippidis 2022). In other words, the client’s financial self-efficacy is an essential determinant of distress tolerance that may keep a client from implementing a recommendation. For example, assume that a client has never heard of the concept of an emergency fund and doesn’t know they should be implementing one. Maybe the client doesn’t know that they should have long-term care insurance. Perhaps the client doesn’t know that Roth IRAs exist and how they differ from traditional IRAs. Thus, knowledge and willingness are closely connected; knowledge informs willingness. A client’s consent and willingness to implement a planner recommendation is meaningless if they don’t know and understand the purpose of the recommendation. Recent research suggests that financial knowledge and anxiety are simultaneously related to financial behaviors (Grable et al. 2019) and can, therefore, delay the implementation of adviser recommendations. In this case, the client is really “in the dark” about what the goal of their financial plan is, which may result in additional anxiety. Their consent or buy-in empowers the SFP, but they are not empowered themselves without knowledge.

Introducing the Initiative Pathway Model (IPM)

It is possible to extend Valsiner’s zone theory by incorporating permittable planning recommendations that the client can either implement themselves or with the SFP’s assistance, as well as considering the client’s knowledge of the recommendation and willingness to implement it. The above discussion presents us with a two-by-two matrix along the dimensions of willingness and knowledge. Learning occurs at the intersection of Valsiner’s ZPD, ZFM, and ZPA, with learning defined as goal achievement via implementing planner recommendations.

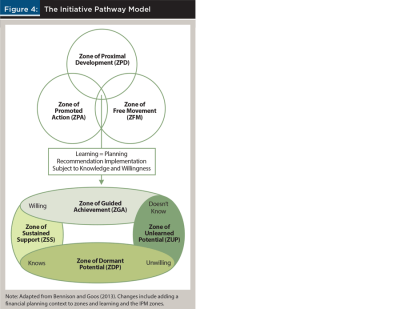

The initiative pathway model (IPM) divides this intersection of the three zones, the “learning zone,” into four zones along the two dimensions of willingness to learn and knowledge of the planning recommendation. In each zone, the client can be empowered by a skilled partner who is either a financial planner, a financial therapist, or similar. However, the support structure offered in these four zones differs. These four zones are discussed next and are presented graphically in Figure 4.

Zone of sustained support (ZSS)—willing and knowing. In the zone of sustained support, the client knows what they should be doing and is either willing to implement the planner’s recommendation or is in the process. An example may be a client who actively contributes to their retirement account.

Zone of guided achievement (ZGA)—willing, not knowing. In the zone of guided achievement, the client is unaware of the benefits of implementing a recommendation, but they would be willing to implement it if they understood the benefits. For example, a client may be interested in investing for the future but have no idea where to start. Another example may be a client saving for a child’s education in a brokerage account. While they want to maximize the amount available for their children’s college education, they are unaware of tax-advantaged vehicles such as 529 plans.

Zone of dormant potential (ZDP)—unwilling, knowing. In the zone of dormant potential, the client knows they should implement a planner recommendation, but they are unwilling to do so. A client may know how important it is to save for retirement and know the various options available, such as 401(k)s or individual retirement accounts (IRAs). Still, the client is either not saving or is unwilling to do so.

Zone of unlearned potential (ZUP)—unwilling, not knowing. Lastly, in the zone of unlearned potential, the client doesn’t know that they should implement a planner recommendation or is unaware of how it would benefit them now or in the long run. Even if they knew how it would help them, they would still be unwilling to implement it. For instance, a client doesn’t see the need for budgeting and is surprised their planner suggests it because they have managed without it and are doing quite well. Maybe a client uses a savings account and is unwilling to utilize fintech tools such as apps because they are unfamiliar with them. Perhaps a client knows that trusts exist in general but has no idea they could be applied to their situation and are unwilling to explore the possibility when the planner suggests them because they heard they only apply to the wealthy. Or a client is not aware that FICO scores exist and has continuously operated on a cash basis because they don’t like credit cards.

Table 1 presents five additional examples, from budgeting and setting up an emergency fund to Roth IRAs, a living will, and diversification. Each example illustrates the four zones across the two factors of willingness to implement a recommendation and knowing how it could be beneficial relative to the client’s financial plan.

Role of the Financial Planner / Therapist in Each Zone

The SFP in each zone plays a different role. So far, we have referred to a financial planner, financial therapist, or financial psychologist as one individual and referred to them as the SFP. However, as we divide the tasks for each zone, it becomes more important to differentiate between the financial planner and a financial therapist/psychologist. For this discussion, a financial planner does not engage in financial therapy but simply gives advice, develops the financial plan, and makes recommendations. Conversely, a financial therapist or financial psychologist integrates money management’s emotional, psychological, and behavioral aspects with the financial planning work, either as an outside fractional behavioral officer or as part of the financial planning practice. It is, of course, also possible that the financial planner is also the financial therapist.

The financial therapy profession is a rather young one, as was discussed recently in a Wall Street Journal article (Lublin 2024). As of May 2024, there were 98 certified financial therapists and 430 members of the Financial Therapy Association. The article acknowledges that the profession is largely unregulated and evolving and consists of both mental health professionals and financial counselors or planners. Anecdotally, there are a variety of ways in which financial planners and therapists can collaborate. For example, financial therapists can be incorporated into a planning practice as part of the team, similar to accountants or lawyers. Arrangements also exist where the financial therapist is compensated either on an hourly basis or as a package, involving the financial therapist as needed. Often, these arrangements involve a marketing or consulting expense on part of the financial planner. An example of a very well-structured model is the Financial Therapy Clinical Institute (www.financialtherapyclinicalinstitute.com). This model starts with a financial therapist, addressing any psychological, emotional, and relational aspects around finances, then moves on to a financial counselor, who works with clients to build a financial structure, and then moves on to the financial planning process. In this model, the various components are contracted out independently, and the institute offers a sliding fee scale and virtual services.

Whatever the exact structure may be, it is important to acknowledge that different roles are important in each zone of the IPM. As Somers (2018) points out, financial planners are well-versed in the intricacies of financial planning, regulations, and financial products. However, they often lack the psychological aspects of financial decision-making. Therefore, professionals should reframe how they approach introducing behavior and emotions into finance (Somers 2018; Bruce 2020).

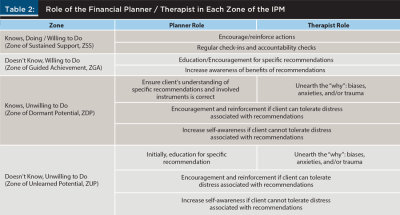

Zone of Sustained Support (ZSS)—Willing and Knowing

The role of the financial planner in the ZSS is the most straightforward. They provide continuing education, encouragement, and support to maintain momentum and adapt to new financial challenges. For example, encouraging clients to stay updated with financial news and suggesting additional tax planning opportunities or investment strategies may help them tailor their approach. As an example from Table 1, perhaps the client is appropriately diversified in their portfolio and understands why this diversification is essential. Regular check-ins and accountability checks with the financial planner also occur in this zone to celebrate milestones and address new challenges by adjusting the financial plan appropriately.

Zone of Guided Achievement (ZGA)—Willing, Not Knowing

The ZGA is the zone where the client is willing to implement a planner recommendation. However, they are either unfamiliar with the underlying tools or unaware of how it would benefit them. As an example from Table 1, maybe the client is unfamiliar with Roth IRAs but would be willing to consider them as an investment vehicle after the planner provides information about them. As another example, maybe the client is unfamiliar with the concept of an emergency fund but finds the idea useful after the planner explains it and is willing to set one up. Therefore, in the ZGA, the planner’s goal is to “guide” the client to the “achievement” of implementing the recommendation. This should be done by explaining and encouraging the benefits of implementing the recommendation, increasing awareness of the underlying financial instrument(s), and improving decision-making to maximize the benefit of the financial plan in the client’s economic life. This process may require additional meetings with the client for implementation. It should be done in a way that continuously tailors the scaffolding of the information based on the event in light of a changing ZDP (Sterbenz et al. 2021).

The ZSS and ZGA are relatively easy to deal with, as they both address situations where the client is willing to implement the planner’s recommendations. Therefore, in both of these zones, the primary job of the financial planner is encouragement and, to a more considerable extent in the ZGA, education. In the ZDP and ZUP, however, the challenge of the financial planner becomes substantially more complicated, as explained below, and the financial planner may require outside assistance in the form of a financial therapist.

Zone of Dormant Potential (ZDP)—Unwilling, Knowing

In the ZDP, the client knows how the recommendation would benefit them and understands the financial instrument(s) involved but is unwilling to implement it. As an example from Table 1, perhaps the client knows they should have a living will. However, they are uncomfortable thinking about end-of-life decisions and are reluctant to implement one. Here, the financial planner should ensure that the client understands the recommendation and that the associated instruments and potential benefits mirror reality. In this situation, the financial planner may want to partner with a financial therapist, as a deeper exploration of the underlying issues can prevent deadlock caused by the chasm between the planner’s recommendations and the client’s refusal to implement them. This disconnect could affect future planner recommendations in a more complicated way.

In this case, the financial therapist’s role is to unearth the “why” of the client’s decision. For example, they may want to determine if the cause of the unwillingness is simply procrastination or caused by any biases, anxieties, or trauma from past or even current events. For example, the client may be subject to present bias (favoring immediate rewards over more considerable future benefits), overconfidence bias, status quo bias, or negativity bias from failed previous attempts to budget. The client may also be anxious about budgeting because of general anxiety around finances or perfectionism in creating a perfect budget. Alternatively, they may be subject to financial trauma, such as childhood experiences of money conflicts or past financial abuse.

Depending on the situation, the therapist should determine the client’s self-efficacy for dealing with the distress caused by the recommendation and if the adaptive traits described in Figure 3 are sufficient to motivate the client to perform the suggested action. For instance, does the client have adequate self-control and psychological flexibility to confront the situation, and can they be motivated to engage in the budgeting action? If there is sufficient flexibility, the therapist should help the client reframe budgeting as a tool for empowerment, shifting any negative perception. Suppose the client exhibits maladaptive traits that lead to avoidance. In that case, the planner can at least increase the client’s self-awareness that their current actions result in a suboptimal financial plan and perhaps address the issue again in the future.

Zone of Unlearned Potential (ZUP)—Unwilling, Not Knowing

The ZUP is the most complicated for a financial planner, as they have to untangle topical ignorance from unwillingness. In this zone, the client doesn’t know how the recommendation will benefit them and/or isn’t familiar with the involved financial instrument(s). Moreover, they are unwilling to perform the action or use the tool once they understand it. As an example from Table 1, a client may have never heard of a Roth IRA and have no interest in opening one, even after the financial planner illustrates the undeniable advantages of using a Roth IRA over other investment options (e.g., a traditional IRA). Here, the planner has to function both as an educator of the recommendation and a therapist to address the client’s unwillingness. As with the ZDP above, the planner may again contract with a financial therapist to address the disconnect between the planner and the client.

In this case, the financial therapist’s role is the same as in the ZDP. However, they may receive the client referral after the planner has unsuccessfully tried to motivate the client to take action by educating them about the benefits of the recommendation. In the Roth IRA example, maybe the client utilizes mental accounting so that investing in a Roth IRA feels like it’s taking away from other priorities. Perhaps the client distrusts financial institutions and/or products and has heard horror stories regarding Roth IRAs from family or friends. Maybe the client has a general fear of incorrect decision-making or is afraid that the rules for the Roth IRA will change in the future. Regarding trauma, maybe there was an inheritance dispute in the family over an inherited Roth IRA that has left the client traumatized.

Once again, depending on the specific situation, the therapist should determine the client’s self-efficacy for dealing with distress. Suppose they have sufficient adaptive traits to implement the planner’s recommendation. In that case, the therapist can work with the client to address past traumas by working through the emotional impact of past experiences. Suppose the client is not ready for the recommendation, perhaps due to experiential avoidance or another maladaptive trait. In that case, the planner can increase the client’s awareness of their current actions’ impact on the financial plan.

The different roles of the financial planner and financial therapist in each of the four zones are illustrated in Table 2. In the table, notice that there is a lot of shared responsibility between the financial planner and the financial therapist. For example, in the ZDP, the planner and therapist both encourage the client and reinforce the implementation of a recommendation if the client can tolerate the associated distress. Similarly, the planner and therapist can ensure that the client has increased self-awareness of the consequences of not implementing the recommendation. In the shared responsibility, the planner’s role is more on the technical side, such as providing specific information within the financial plan resulting from implementing or not implementing the recommendation. The therapist’s role, on the other hand, is to address the behavioral and emotional side of the discussion.

To summarize, the planner’s role in the ZSS is to encourage and reinforce the recommendations the client is already performing or willing to perform. In the ZGA, where the client doesn’t know how the recommendation is beneficial or doesn’t understand the underlying instruments but is willing to implement it, the planner’s role is education and encouragement to increase client awareness and improve decision-making. In the ZDP, where the client understands the recommendation’s purpose but is unwilling to engage, the role of the financial planner shifts to that of a financial therapist. They aim to unearth the “why” behind the decision inertia, whether it be biases, anxieties, or trauma. If the client’s self-efficacy leads to a resolution of the issues to deal with the distress resulting from the emotion, the recommendation can be implemented. If there is insufficient self-efficacy, and the recommendation is not implemented, then at least self-awareness can be improved. Lastly, in the ZUP, where the client doesn’t know the recommendation is beneficial and is unwilling to implement it, the financial planner first attempts to educate the client. When the client is reluctant to implement the recommendation, the planner’s role again shifts to one of financial therapist, as in the ZDP.

Zone Identification

Given the different roles of financial planners and financial therapists in the four zones, depending on the client’s willingness to implement a recommendation and their knowledge of its usefulness or the underlying financial instruments, it is vital to classify clients into a zone. This should be done for each recommendation the client is being asked to implement. This assessment of the client’s willingness and familiarity with the planner’s recommendation functions as a checkpoint to determine if the recommendation is immediately implementable or if involving a financial therapist in the process would be beneficial. There are, of course, a variety of ways to structure such a checkpoint. For example, the following four questions can be used to determine the client’s knowledge and willingness to move forward. The first addresses knowledge, while questions two through four address different aspects of willingness.

1. How familiar are you with [specific recommendation, e.g., budgeting, emergency fund, etc.]?

Purpose: To assess the client’s knowledge level about the planner’s recommendation. For a more complete picture, the planner could also ask if the client has utilized the recommended action previously.

2. On a scale of 1–10, how ready are you to implement [specific recommendation] in your financial plan, either by yourself or with your financial planner’s help?

Purpose: To assess the client’s willingness to implement the recommendation.

3. In the past, when considering a new financial action or tool, what factors have most influenced your decision to move forward with it?

Purpose: This allows the client to state factors that generally affect their willingness and may reveal underlying biases, anxieties, fears, or traumas.

4. If there were no obstacles, would you be willing to start [specific recommended action] today? Why or why not?

Purpose: This question highlights that the action or tool is in the ZFM, assuming no obstacles. With that specified, a negative answer to the question would reveal any internal resistance, such as financial anxiety or fears.

To untangle knowledge and willingness, asking the first question before going through the remaining questions is a good idea. If there is no knowledge, the planner should stop and make an effort to provide an explanation to the client of the planner’s recommendation and then move on to the willingness questions.

The client can be classified into one of the four zones based on their responses to these questions. If the client understands the recommended action and has a history of proactive decision-making, they would be in the ZSS. If the client has knowledge but is unwilling to proceed with the recommendation, they would be in the ZDP. If the client shows general willingness but does not quite understand the recommendation or the benefits associated with implementing it, they would be in the ZGA. If the client does not understand the recommendation and is unwilling to move forward after the planner explains its utility, they would be in the ZUP before and in the ZDP after the explanation. Using these four questions before each decision in the financial plan provides a helpful checkpoint to determine if a financial therapist needs to be involved in the process if the client is in the ZDP or ZUP.

Discussion and Implications

Although many U.S. households utilize financial planners, the advice provided by these planners is often not implemented (Somers 2018) for a variety of reasons, including resistance to change, emotional barriers, financial anxiety, or trauma (Klontz, Horwitz, and Klontz 2015; Lerman and Bell 2006; Ross and Coambs 2018; Ross, Johnson, and Coambs 2022). In addition, existing datasets make it difficult to measure the actual implementation of adviser recommendations (Dew, Dean, Duncan, and Britt-Lutter 2020; Dew and Xiao 2011), and the implementation of planning recommendations is contingent on both client knowledge and their willingness to implement the recommendation (Bartholomae, Kiss, and Pippidis 2022).

While previous research has incorporated existing cognitive models (Vygotsky 1978) that take into account the breakdown of information to clients by appropriately scaffolding it and the ability of clients to implement planner recommendations with the help of a skilled financial planner (Sterbenz et al. 2021), knowledge and willingness have not been explicitly incorporated into a model that classifies clients into zones based on their understanding of the planner recommendation benefits and financial instruments as well as their willingness to implement the recommendation. The current research extends both Valsiner’s (1997) zone theory, which incorporates allowable recommendations, and Veilleux’s (2022) theory of momentary distress, which highlights a client’s willingness to tolerate the distress associated with a planner recommendation. Incorporating both theories highlights the importance of possible implementation resistance due to maladaptive traits related to a client’s unwillingness to experience distress associated with implementation, which in turn depends on the client’s level of self-efficacy for tolerating distress. Moreover, that lack of financial self-efficacy is significant in explaining financial anxiety (Lee, Rabbani, and Heo 2023), highlighting the importance of client self-efficacy in determining their willingness to implement the recommendation.

A model is developed here highlighting the importance of client knowledge and willingness to implement a planner’s recommendation. By classifying clients into four zones based on their understanding of the proposed recommendation and their willingness to implement it, it is possible to identify the point at which a financial therapist may have to be involved in the financial planning process to identify any underlying biases, fears, anxieties, or trauma and address any implementation resistance. If the resistance persists even after education and encouragement by the planner and participation of a financial therapist, then at a minimum, the client’s awareness of the consequences of non-implementation is increased.

This model has several important implications. First, by incorporating both Vygotsky’s and Valsiner’s theories, a clearer picture of the financial planning profession is provided that accounts for legal, regulatory, and personal constraints in addition to the financial planner’s function as a skilled partner. Second, both skills/knowledge and behavioral and emotional readiness are essential for clients to implement recommendations (Bartholomae, Kiss, and Pippidis 2022), and both are considered part of the model. The IPM developed here allows planners to utilize different approaches for their clients based on their understanding of the planner recommendations and their willingness to implement them, which in turn emphasizes the need for a distinction between financial planners who only focus on advice and planning and financial therapists or psychologists who address emotional, psychological, and behavioral aspects of financial planner recommendations. The IPM can potentially empower planning clients by utilizing reinforcement, encouragement, education, and psychological or behavioral interventions, where appropriate, based on the client’s zone. While there are multiple ways to accomplish this, four short questions are suggested here.

In conclusion, utilizing the IPM illuminates the importance of a holistic approach to financial planning that addresses issues that can interfere with the successful implementation of planner recommendations to achieve financial goals. At best, such an approach results in an optimal financial plan. At worst, it will result in a client’s awareness of how non-implementation of advice will affect them. Both cases result in a stronger planner–client relationship and increased trust. What sets the IPM apart is its detailed framework for identifying and addressing the specific reasons behind client resistance, such as lack of knowledge, emotional barriers, or past traumas. The IPM not only categorizes clients based on their willingness and understanding but also provides specific steps for financial planners and therapists to jointly enhance client outcomes.

Citation

Schnusenberg, Oliver. 2025. “Navigating Client Engagement: Considering Client Knowledge and Willingness.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (2): 66–82.

Endnote

- An exception is a Rule 72(t) annuitization, which allows individuals to take early withdrawals from their retirement accounts without incurring the usual 10 percent early withdrawal penalty. This rule is particularly applicable to those under the age of 59½. To qualify for the penalty exemption, the withdrawals must be taken as substantially equal periodic payments (SEPPs) for a minimum of five years or until the account holder reaches age 59½, whichever is longer. The payments can be calculated using one of three IRS-approved methods. Other exceptions can be viewed at www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-exceptions-to-tax-on-early-distributions.

References

Bartholomae, S., D. E. Kiss, and Pippidis, M. 2022. “Financial Education for Adults: Effective Practices and Some Recommendations.” In The Routledge Handbook of Financial Literacy. Edited by G. Nicolini and B. J. Cude. Routledge: 204–222.

Bennison, A. 2022. “Using Zone Theory to Understand Teacher Identity as an Embedder-of-Numeracy: An Analytical Framework.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 50 (2): 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2020.1828821.

Bennison, A., and M. Goos. 2013. “Exploring Numeracy Teacher Identity: An Adaptation of Valsiner’s Zone Theory.” Joint AARE Conference, Adelaide 2013: 1–10.

Bruce, E. 2020. “Book Review: Advice that Sticks.” Journal of Financial Therapy 11 (1): 7. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1232.

Chaffin, C.R. 2015. “Communicating the Financial Planning Recommendations.” In CFP Board Financial Planning Competency Handbook. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119642473.ch75.

Conway, C. C., K. Naragon-Gainey, and M. T. Harris. 2021. “The Structure of Distress Tolerance and Neighboring Emotion Regulation Abilities.” Assessment 28 (4): 1050–1064. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191120954914.

Cude, B. J. 2022. “Defining Financial Literacy.” In The Routledge Handbook of Financial Literacy. Edited by G. Nicolini and B. J. Cude. Routledge: 5–17.

Dew, J. P., and J. J. Xiao. 2011. “The Financial Management Behavior Scale: Development and Validation.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 22: 43–59. http://afcpe.org/journal-articles.php?volume=387&article=403c.

Dew, J., L. Dean, S. F. Duncan, and S. Britt-Lutter. 2020. “A Review of Effectiveness Evidence in the Financial-Helping Fields.” Family Relations 69 (3): 614–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12445.

Erbil, D. G. 2020. “A Review of Flipped Classroom and Cooperative Learning Method Within the Context of Vygotsky Theory.” Frontiers in Psychology 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01157.

Esteban-Guitart, M. 2018. “The Biosocial Foundation of the Early Vygotsky: Educational Psychology Before the Zone of Proximal Development.” History of Psychology 21 (4): 384–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/hop0000092.

Grable, J. E., K. L. Archuleta, M. R. Ford, M. Kruger, J. Gale, and J. Goetz. 2019. “The Moderating Effect of Generalized Anxiety and Financial Knowledge on Financial Management Behavior.” Contemporary Family Therapy 42 (1): 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-019-09520-x.

Haupt, M. 2022. “Measuring Financial Literacy: The Role of Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes.” In The Routledge Handbook of Financial Literacy. Edited by G. Nicolini and B. J. Cude. Routledge: 79–95.

Klontz, Brad T., Edward J. Horwitz, and Ted P. Klontz. 2015. “Stages of Change and Motivational Interviewing in Financial Therapy.” In Financial Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice. Edited by Bradley T. Klontz, Sonya L. Britt, and Kristy L. Archuleta. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing: 347–362.

Lass, A. N. S., J. C. Veilleux, H. L, DeShong, and E. S. Winer. 2023. “What Is Distress Tolerance? Presenting a Need for Conceptual Clarification Based on Qualitative Findings.” Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 29: 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2023.05.003.

Lee, J. M., A. Rabbani, and W. Heo. 2023. “Examining Financial Anxiety Focusing on Interactions Between Financial Knowledge and Financial Self-Efficacy.” Journal of Financial Therapy 14 (1). https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1279.

Lee, Y. G., H. H. Kelley, and J. M. Lee. 2023. “Untying Financial Stress and Financial Anxiety: Implications for Research and Financial Practitioners.” Journal of Financial Therapy 14 (1): 41–65. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1293.

Lerman, Robert I., and E. Bell. 2006. “Financial Literacy Strategies: Where Do We Go from Here?” Networks Financial Institute Policy Brief 2006-PB-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.923448.

Lublin, J.S. 2024, May 16. “Money Angst? You Might Consider a Financial Therapist.” Wall Street Journal. www.wsj.com/personal-finance/financial-therapist-money-anxiety-b85ab0f4.

Lyons, A. C., and J. Kass-Hanna. 2022. “A Multidimensional Approach to Defining and Measuring Financial Literacy in the Digital Age.” In The Routledge Handbook of Financial Literacy. Edited by G. Nicolini and B. J. Cude. Routledge: 61–76.

Ross, D. B., and E. Coambs. 2018. “The Impact of Psychological Trauma on Finance: Narrative Financial Therapy Considerations in Exploring Complex Trauma and Impaired Financial Decision Making.” Journal of Financial Therapy 9 (2): 37–53. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1174.

Ross, D. B., E. Johnson, and E. Coambs. 2022. “Trauma of the Past: The Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Adult Attachment, Money Beliefs and Behaviors, and Financial Transparency.” Journal of Financial Therapy 13 (1): 39–59. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1280.

Shabani, K., M. Khatib, and S. Ebadi. 2010. “Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development: Instructional Implications and Teachers’ Professional Development.” English Language Teaching 3 (4): 237–248. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v3n4p237.

Somers, M. 2018. Advice That Sticks: How to Give Financial Advice That People Will Follow. Practical Inspiration Publishing.

Sterbenz, Elizabeth, Dylan Ross, Raylee Melton, Jed Smith, Megan McCoy, and Blain Pearson. 2021. “Using Scaffolding Learning Theory as a Framework to Enhance Financial Education with Financial Planning Clients.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (12): 70–80.

Valsiner, J. 1997. Culture and the Development of Children’s Action: A Theory for Human Development. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Veilleux, J. C. 2022. “A Theory of Momentary Distress Tolerance: Toward Understanding Contextually Situated Choices to Engage with or Avoid Distress.” Clinical Psychological Science 11 (2): 357–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026221118327.

Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

White, K. J., and S. J. Heckman. 2016. “Financial Planner Use Among Black and Hispanic Households.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (9): 40–49.

Wood, D., J. S. Bruner, and G. Ross. 1976. “The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17 (2): 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.