Journal of Financial Planning: February 2025

Christina Lynn, Ph.D., CFP®, AFC, CDFA, is a practice management consultant at Mariner Wealth Advisors (www.marinerwealthadvisors.com). She specializes in the psychology of financial planning, divorce finances, estate planning, and digital assets. Her financial planning style can be described as holistic and evidence-based, with a focus on life-planning and innovation.

NOTE: Click the image below for a PDF version.

JOIN IN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Why doesn’t the quant-focused adviser close the most business? And why does the adviser who dominates conversations, talking more about themselves than the client, struggle to connect? Understanding the “why” can transform your practice. While technical prowess is crucial, it’s not enough to earn clients’ trust and loyalty (McCoy et al. 2022). The missing piece is often emotional intelligence—the key to transforming good advisers into great ones.

Emotional intelligence involves understanding and processing both your own emotions and those of others and using that understanding to guide your thoughts and actions (Mayer et al. 2008). Employing emotional intelligence is about being self-aware, in control of what you say and how you respond, and reading non-verbal cues. The good news is we can all improve our emotional intelligence skills, regardless of our starting point.

A recent study published by eMoney (2024) demonstrated that advisers with higher emotional intelligence skills experienced better outcomes, including (a) higher client motivation; (b) increased levels of trust; (c) reduced financial anxiety; (d) more referrals; (e) greater client loyalty; and (f) higher client satisfaction. Emotional intelligence is a leading indicator of a client’s trust and commitment and will become increasingly important as the technical aspects of financial planning become commoditized and artificial intelligence increasingly handles routine tasks. The secret ingredient to our enduring value is the human connection, which cannot be outsourced to software.

To help advisers enhance their emotional intelligence skills, a tool referred to as the financial planning emotional intelligence (FPEQ) scorecard was developed. The FPEQ scorecard utilizes conversation techniques from motivational interviewing (MI), an evidence-based communication approach that empowers clients to make positive changes (Miller and Rollnick 2023). Miller and Rollnick, the founders of MI, describe MI as an effective framework for training professionals to enhance emotional intelligence skills due to its focus on empathy, reflective listening, and collaboration. This makes MI particularly useful for training financial advisers in developing EQ skills. MI is used in various professions, including education (Kaltman and Tankersley 2020), healthcare (Dunhill et al. 2014), and corrections (McMurran 2009). At its core, MI guides the professional to utilize accurate empathy as a base for all communication. The format of the FPEQ scorecard was inspired by the motivational interviewing training integrity coding system, which assesses adherence to MI techniques (Moyers et al. 2015). It has been adapted for financial planning to enhance communication skills through structured debriefing and self-reflection. The purpose of the FPEQ scorecard is to (a) practice and improve communication skills; (b) receive immediate feedback; (c) identify strengths and weaknesses; and (d) develop greater self-awareness.

The FPEQ Scorecard Categories

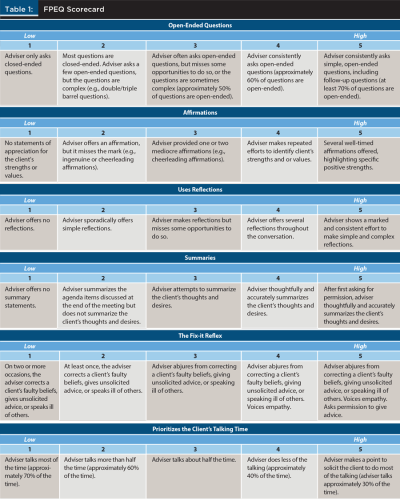

The FPEQ Scorecard consists of 10 categories, each based on an MI conversation technique (see Table 1). Here are the categories:

- Open-ended questions offer the client broad latitude in responding, drawing out their experiences and perspectives. They are structured to avoid yes/no answers, double-barreled questions, and overly complex questions.

- Affirmations are statements acknowledging the client’s strengths or values. Affirmations are tricky because they can easily come across as cheerleading, which doesn’t land well for many people. Highlighting a client’s genuine strengths or values is a more effective strategy for crafting affirmations.

- Reflections are statements intended to mirror the meaning of what a client has said. Think of an iceberg. What your client says verbally represents only a small portion of the much bigger issues invisibly looming underwater. A reflection is your best guess at what is going on below the surface. We will not always accurately discern what’s happening beneath the surface, and that’s OK. Clients can correct us if our guess is off. Reflections help them explore whether our perceptions align with their feelings. Remember, reflections should always be statements, not questions—end your sentences with a definitive tone. Instead of asking if they’re feeling overwhelmed, say, “You are feeling overwhelmed.” Ideally, use twice as many reflections as questions, as they are a powerful tool for demonstrating accurate empathy.

- Summaries are employed by organizing the client’s thoughts and offering them back as a string of reflections. Summaries are also useful for pivoting a conversation to another topic—a gentle nudge in a new direction or returning to the original direction prior to going off-topic. A helpful acronym for employing summaries is BIJO (Rosengren 2024):

B = Brief. Long summaries lose people. No rambling.

I = Intentional. Select only the key points shared to include in your summary.

J = Juxtaposed. For example, “One part of you feels this way ___; another part of you feels this way ___.” This strategy can help lower their defenses and let them know that you get them.

O = Organized. Summarize the key points in a clear and logical manner. - The fix-it reflex is the natural desire of an adviser to prevent financial harm by correcting perceived problems. We are prone to explaining what our clients and prospects should be doing. The fix-it reflex is a natural response because we readily spot mistakes and can quickly identify solutions. After all, clients are paying for our expertise. We say things like, “No, don’t do this, try this instead.” If a prospect assumes they can simply use the 4 percent rule for retirement distributions, it is tempting to reply, “It’s a lot more complicated than that. Let me show you the necessary calculations and stress tests.” The fix-it reflex is closely linked to the “expert trap,” where we detect a problem and promptly offer a solution, showcasing our expertise. While this is well-intentioned, it can inadvertently undermine the client’s sense of autonomy. We can come across as bossy, impatient, shaming, pressuring, not listening. Clients may become disengaged if they feel we’re not fully listening to their actual concerns, potentially sparking an invisible power struggle between us and them.

- “Prioritizes the Client’s Talking Time” is a category dedicated to ensuring the client does most of the talking. A key component of building emotional intelligence skills is to talk less and listen more.

- “Employ Pauses” quantifies the adviser’s ability to employ intentional pauses to let the client process their thoughts. Clients need time to process their thoughts, and advisers often do not give them enough time to do so. This category is designed to retrain the adviser’s brain to view silence as a sign of respect from the adviser to the client, to hold space for them as they think, rather than viewing the silence as awkward or a waste of time.

- “Avoids Financial Jargon” assesses the adviser’s habit of using everyday language, avoiding technical terms such as equities, fixed income, drawdown, options, hedging, Sharpe Ratio, beta, delta, tax loss harvest, Monte Carlo, standard deviation, asset classes, leverage, risk-adjusted returns, SLATs, ILITs, custody, etc.

- Client-led agenda is a practice where a client’s needs, goals, and priorities drive the structure and focus of the meeting. Instead of the adviser steering tightly around the agenda, the client actively shapes it, ensuring their concerns and objectives are prioritized.

- “Reading Non-Verbal Cues” is a category that assesses the ability to pay close attention to clients’ body language, facial expressions, and tone during meetings.

How to Use the FPEQ Scorecard

- Conduct a client meeting. The adviser conducts a client meeting with an observer present. This process can be simulated with team members for practice or done with actual clients (with permission).

- Rate communication techniques. The observer, remaining silent throughout the meeting, rates the adviser’s communication techniques in each category of the FPEQ scorecard.

- Review the scorecard. After the meeting, the observer and adviser review the FPEQ scorecard together. The adviser can also reflect on it independently to identify areas of strength and opportunities for improvement.

When to Use the FPEQ Scorecard

The FPEQ scorecard can serve multiple purposes. It can be tailored for individual advisers seeking to improve their communication skills or implemented organization-wide to elevate the overall client experience. Additionally, it can be used for new hire training to ensure communication standards.

Case Study Demonstrating How to Utilize the FPEQ Scorecard

1. Prepare for the Client Meeting

Adviser Inigo contacts his long-time client, Fezzik, in advance to seek permission for Observer Westley to attend their upcoming meeting. Observer Westley will prepare Adviser Inigo by outlining two key points: (1) he will remain silent during the meeting, and (2) his presence is solely for training purposes. His goal is to create a positive training environment that fosters improvements in communication skills, ultimately enhancing client motivation, satisfaction, and loyalty.

2. Conduct the Meeting and Rate Communication Techniques

After introducing Observer Westley, Adviser Inigo conducts the financial planning meeting per his normal agenda and protocol. Westley remains silent throughout the meeting, completing the FPEQ scorecard to rate Inigo’s communication skills in the 10 categories as outlined in Table 1.

3. Review the Scorecard in a Post-Meeting Debrief

Observer Westley and Adviser Inigo review the FPEQ scorecard results together. Westley focuses on providing positive feedback while allowing Inigo time to reflect on his answers and demonstrating effective use of the FPEQ scorecard categories during the debriefing. The FPEQ scorecard is designed to be intuitive, allowing observers to participate without specialized training. While some observers may not easily recognize specific techniques (e.g., reflections), the value lies in the overall experience, ensuring the adviser gains meaningful insights regardless. Below is a transcript illustrating how the debriefing meeting could unfold:

Observer Westley: “Great job today, Inigo. Let’s review the FPEQ scorecard results together. What do you think you did well in the meeting?”

Adviser Inigo: “I felt good about encouraging Fezzik to lead the conversation.”

Observer Westley: “That was one of your highest-scoring areas. Prioritizing the client’s talking time helps shift the power dynamic and fosters a sense of partnership. What surprises you about the results?”

Adviser Inigo: “I didn’t realize how much I needed to incorporate reflections.”

Observer Westley: “Reflections are a powerful tool for helping clients feel at ease and deepening your connection with them. How are you currently using reflections in your practice?”

Adviser Inigo: “I know reflections are part of active listening, and they involve mirroring back what the client said.”

Observer Westley: “Exactly. That’s a simple reflection. A complex reflection, on the other hand, involves guessing what’s going on beneath the surface. Complex reflections are great because they show the client you genuinely care about understanding their perspective and can also help steer the conversation. Do you have any other questions about the scorecard?”

Adviser Inigo: “I scored a 2 on the fix-it reflex. That’s a new term for me.”

Observer Westley: “The fix-it reflex is common among professionals. We’re often used to being the expert, which makes us eager to help by offering advice. Reflecting on the meeting, how do you think the fix-it reflex showed up?”

Adviser Inigo: “I might have jumped the gun by presenting investment options too soon. I should have helped them explore their goals and motivations first.”

Observer Westley: “That’s great insight. Just being aware of the fix-it reflex in daily conversations is helpful. So, what would you like to focus on improving next?”

Adviser Inigo: “I’d like to work on reflections and summaries to better address client concerns.”

Observer Westley: “Sounds like a solid plan. What are your next steps?”

Adviser Inigo: “I’m going to practice reflections at home with my family, especially with my kids. I’d also like to schedule another training session like this, if that’s OK with you.”

Observer Westley: “Of course. Let’s get that scheduled.”

Conclusion

The FPEQ scorecard is a practical tool for enhancing financial advisers’ emotional intelligence and, consequently, their communication effectiveness. By practicing with the FPEQ scorecard, advisers can develop a robust emotional intelligence filter, ensuring each client interaction is meaningful and productive. In an AI-driven world, this human touch remains our greatest asset.

References

Dunhill, D., S. Schmidt, and R. Klein. 2014. “Motivational Interviewing Interventions in Graduate Medical Education: A Systematic Review of the Evidence.” Journal of Graduate Medical Education 6 (2): 222–236.

eMoney. 2024. “The New Value Proposition for Advisors: How Combining Technology and Financial Psychology Transforms Client Outcomes.” https://emoneyadvisor.com/resources/ebooks/the-new-value-proposition-for-advisors/.

Kaltman, Stacey, and Amelia Tankersley. 2020. “Teaching Motivational Interviewing to Medical Students: A Systematic Review.” Academic Medicine 95 (3): 458–469. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003011

Mayer, J., P. Salovey, and D. Caruso. 2008. “Emotional Intelligence: New Ability or Eclectic Traits?” American Psychologist 63 (6): 503–517. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.6.503.

McCoy, M., I. Machiz, J. Harris, C. Lynn, D. Lawson, and A. Rollins-Koons. 2022. “The Science of Building Trust and Commitment in Financial Planning: Using Structural Equation Modeling to Examine Antecedents to Trust and Commitment.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (12): 68–89.

McMurran, M. 2009. “Motivational Interviewing with Offenders: A Systematic Review.” Legal and Criminological Psychology 14 (1): 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532508X278326.

Moyers, T., J. Manuel, and D. Ernst. 2015. Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Coding Manual 4.2.1. Unpublished manual. https://motivationalinterviewing.org/sites/default/files/miti4_2.pdf.

Miller, W., and S. Rollnick. 2023. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change and Grow. Fourth edition. The Guilford Press.

Rosengren, D. 2024. Someone Good to Talk To. Motivational interviewing training workshop on June 7, 2024.