Journal of Financial Planning: January 2023

Executive Summary

- Delaying Social Security can be framed as longevity insurance that helps to support the increasing costs associated with living a long life. It provides inflation-adjusted lifetime benefits for a retiree and a surviving spouse, and the monthly benefits will be 77 percent larger in inflation-adjusted terms for those who claim at 70 instead of at 62.

- But sometimes this insurance value is questioned, with the idea being that an early claiming decision will provide an opportunity for investments to grow and support better retirement outcomes.

- Simple extrapolations about suggesting that claiming Social Security early and investing the benefits to earn historical stock market returns misses several important points about retirement income: retirees may not invest this aggressively, and retirees must fund spending from assets and do not experience simple time-weighted returns.

- To generate the returns needed to beat the benefit of delaying Social Security, there would need to be a high tolerance for risk and an aggressive asset allocation.

- We find evidence using the historical data that it is uncommon for investment returns to beat the implied benefit of delaying Social Security for long-lived retirees even with relatively aggressive asset allocation strategies.

Wade D. Pfau, Ph.D., CFA, RICP, is the program director of the retirement income certified professional (RICP) designation and a professor of retirement income at The American College of Financial Services in King of Prussia, PA, as well as a co-director of the college’s Center for Retirement Income.

Steve Parrish, J.D., RICP, AEP, ChFC, CLU, is co-director of the Center for Retirement Income at The American College of Financial Services, where he is also adjunct professor of advanced planning.

NOTE: Please click the images below for PDF versions.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Few would disagree that Social Security is a valuable retirement income source, even for affluent and high-net-worth retirees. More pressing is the question of when participants should file for their retirement benefits—as early as age 62 or as late as age 70? The usual filing debates focus on the claimant’s other retirement income sources, investments, and tax situation. Proponents of delayed Social Security filing emphasize that the participant will ultimately get more income, that the ongoing payments act as an insurance benefit that covers the tail risk of longevity, and that delayed filing helps to avoid negative tax consequences such as the tax torpedo or Medicare income-related monthly adjustment amounts (IRMAA) to premiums. In contrast, those who advocate filing early point to situations where the claimant needs the money now, the concern over whether the government may fail to pay projected benefits, the loss in benefits caused by a premature death, and the idea that if benefits are claimed early then they can be invested to earn higher long-term returns.

Several of these matters do suggest a justification for claiming earlier outside of this article’s focus. Those with legitimate medical reasons to project a shorter longevity and those who simply have no alternative and need to access these funds might reasonably decide that claiming earlier is their best option. This article focuses on the latter issue—which of the claiming strategies will end up leaving the largest legacy. In other words, if the claimant does not expect to spend down their entire investment portfolio during their lifetime, which claiming strategy ultimately leaves more inheritance? Specifically, what is the opportunity cost to delaying benefits in terms of what is missed by claiming benefits earlier to reduce pressure on investment distributions and leave more assets exposed to market returns?

Affluent retirees may have multiple retirement income sources (e.g., annuities and pensions), and multiple sources of retirement capital (e.g., 401(k) and personal investments). Because this income and capital will not necessarily be exhausted during retirement, these retirees want to be efficient with their income strategy. The three primary factors in determining the most efficient approach are returns, taxes, and risk.

- Returns. Social Security has a fixed return factored into the primary insurance amount (PIA) calibrated to actuarial life expectancies and interest rates in 1983. In contrast, the return on retirement capital such as a 401(k) or investment account has a variable return, and this return represents opportunities for high yield, but at a risk.

- Taxes. Retirement income sources represent a slew of varying taxes, from capital gains and ordinary income to special taxes associated with the Social Security benefit itself. Further, the timing of recognition of income can significantly affect tax efficiency, particularly because the retiree’s tax situation may change.

- Risk. With opportunity comes risk. Risk can include such issues as inflation, sequence of returns, government default, liquidity, and diminished capacity.

The above issues do not lend themselves to easy quantification. This article will, however, address a key part of the analysis. Our research attempts to address this question: while a participant stands to receive more income later in life by delayed filing, what about the possibility of filing for Social Security as early as possible, which reduces the pressure to draw from investments to cover spend-ing needs, to ultimately yield more wealth available as a legacy? The issue is whether Social Security is a form of longevity insurance or an opportunity for investment, and our analysis utilizes historical market data to suggest possible answers.

Insurance or Investment Opportunity?

Should Social Security be positioned as insurance to provide a source of inflation-adjusted spending protection against the risk of outliving financial assets in retirement, which would imply value for delaying the claiming decision, or is Social Security better positioned as an opportunity to leverage stronger investment portfolio growth by claiming benefits early to reduce short-term portfolio distribution needs? Starkly contrasting opinions about this question exist within the financial services world. There is no correct answer that applies for everyone, but what this research seeks to do is to at least provide evidence about how different claiming strategies would have performed using historical market data. We hope this will provide a better sense about the potential opportunities and risks related to these decisions. To date, we are not aware of such analysis. Most arguments in favor of claiming early tend to assume a fixed rate of return for investments that is typically matched with historical average stock market returns, providing little context to what might happen with real-world investment portfolios during the pivotal early retirement years.

Regarding the view toward treating Social Security as longevity insurance, Social Security retirement benefits are inflation-adjusted and government-backed. With lifetime cash flows, these benefits mitigate longevity, inflation, and market risk for retirees. For risk-averse retirees who would otherwise invest more heavily in bonds, which do not provide longevity protection, the insurance value of Social Security may be even stronger because there would otherwise be less potential for upside growth with investments. A unique aspect of Social Security is that it also provides spousal and survivor benefits. The insurance perspective is to not focus on regret relating to delaying benefits and then experiencing a premature death, but to focus on avoiding a situation in which retirees outlive their assets. Patience with Social Security may help individuals manage this longevity risk. The view of Social Security as insurance is to delay claiming and to take advantage of the delay credits to obtain the maximum inflation-adjusted lifetime income.

The contrasting viewpoint is to file for Social Security early to invest the benefits into the financial portfolio, or to otherwise use benefits to cover expenses and reduce the withdrawal needs from the investment portfolio to better preserve those assets. With this approach, it is hoped that there will be more lifetime wealth by exposing more investment assets to market returns. The argument is that it makes no sense to delay Social Security because a financial adviser can invest the benefits and earn a higher return for their clients over the long run. Certainly, if realized investment returns are high enough, claiming early is advantageous. But there has been little investigation about the likelihood of achieving the returns needed to allow an early claiming decision to translate into greater lifetime wealth.

We will investigate this matter using two case studies applied to rolling periods from the U.S. historical data since 1871. Social Security claiming strategies involve deciding on which age to claim retirement benefits. Those benefits can be claimed starting at age 62, and additional credits are available for delaying benefits up until age 70. For a single person, the claiming decision is simply a matter of picking the start date for benefits. The decision is more complicated for couples or singles with dependents, though. For couples, each spouse must consider when to claim their own benefit, when to claim their spousal benefit (for the few left who can make this distinction), and the impact of their claiming decision on whether their spouse has access to a spousal benefit and the size of a survivor benefit.

The primary insurance amount (PIA) measures the benefit available at the full retirement age (FRA). Benefits adjust upward or downward depending on when they start relative to the FRA. For each month of delay beyond the full retirement age, the benefit increases by 0.67 percent. This sums to an 8 percent increase in benefits relative to the PIA per year (not compounded). For each month of early uptake relative to the FRA, the benefit reduces by 0.56 percent per month for the first 36 months of early uptake, and by an additional 0.42 percent for any months beyond that. In inflation-adjusted terms, those with an FRA of 67 will experience a monthly benefit that is 77 percent larger by delaying to age 70 compared to claiming at 62, and 24 percent larger than claiming at full retirement age.

Since claiming earlier means more years of benefit receipt, while claiming later means fewer years, when these adjustments were designed in 1983, they were intended to be actuarially fair. This means it should not matter what age one claims their benefit for single individuals who had an average life expectancy in 1983. However, those calculations for actuarial fairness no longer hold for today’s single individuals who have a higher life expectancy, face today’s lower interest rates, or have someone who may receive survivor benefits from their record. Presently, it is not necessary to live to average life expectancy before receiving net positive benefits from delayed filing for Social Security.

A Survey of Literature Regarding Claiming Strategies

The research below seeks to provide evidence about how different claiming strategies would have performed using historical market data. This analysis factors in considerations such as federal income taxes, asset location, and retirement spending patterns. While there is no lack of literature concerning claiming strategies for Social Security, much of the literature focuses on individual aspects of the decision process, whether it be markets, taxes, or government policy. Each of these aspects plays into the ultimate filing decision for an individual or couple.

Fundamental to the claiming decision is understanding how the system works for retirees. Pfau (2021) walks readers through the steps required to have a firm understanding about Social Security claiming. This source describes how benefits are calculated, and how to factor in issues such as spousal and survivor benefits for couples, dependent benefits, and benefits for divorcees. It also describes the two main philosophies related to claiming Social Security: treating Social Security as longevity insurance or focusing on the breakeven age for when delaying benefits will pay off.

Social Security also offers some limited flexibility in managing claiming decisions. For example, there is the possibility of a reversible delay in filing. Levine (2022) notes that the ability to file for benefits retroactively provides the opportunity to make better Social Security claiming decisions.

Return on Assets

Implicit in any discussion of which strategy provides the highest legacy value is the issue of return on assets. This issue is challenging because Social Security as an asset is best described as a stream of payments, contingent on survival, that potentially increases annually to reflect the cost of living. There are few assets available with comparable features.

Some sources use Monte Carlo simulation to calculate the probability of success of various claiming strategies. Monte Carlo simulations provide a way to develop sequences of random market returns fitting predetermined characteristics. This is used to test how financial plans will perform in a wider variety of good and bad market environments. A downside for Monte Carlo simulations is that they do not reflect other characteristics of the historical data not incorporated into the assumptions, and they may not create extreme low or high returns as frequently observed with real historical data (Pfau 2016). For instance, historical data may include mean reversion characteristics or persistence for a variable’s values over time in a manner not picked up by a typical Monte Carlo simulation that assumes the simulated returns are independent and identically distributed in each period. Still, Monte Carlo simulations can be a useful means of assessing various claiming strategies, and represent an opportunity for further research.

Another comparison approach is to calculate the net present value of the various strategies. This, of course, is dependent on using a realistic discount rate. Any comparison of claiming strategies made by discounting to present value must reflect the inflation-adjusted real interest rate associated with Social Security payments. Duffy, Finke, and Blanchett (2021) considered this approach when addressing claiming strategies for higher-earning women. Using the example of healthy and average-health men and women, they found that by calculating the expected net present value using TIPS rates, the value of delayed claiming was significant, particularly for married healthy women. Further, the benefit from delayed claiming for healthy women can be nearly twice the benefit for average males.

In their article, they also considered how these outcomes might change if there were an increase in the real discount rate (they assumed 2 percent) and a possible reduction in Social Security benefits due to depletion of the Social Security trust fund (they assumed a 21 percent reduction occurring in 2026). They found no scenario where healthy women do not increase their expected retirement wealth from delayed claiming.

Risk of Reduced Benefits

Beginning in the year 2021, Social Security retirement benefits paid out began to exceed the growth in the Social Security trust fund. This has led to significant literature addressing “the insecurity of Social Security” (Parrish 2020). The Social Security Administration Board of Trustees 2022 annual report currently projects that the fund will deplete in 2034, and then benefit payments will only be 77 percent of current benefits. Parrish identifies two myths in assessing the risk of Social Security underfunding. One myth is that because of the risk of trust fund depletion, retirees should file early to maximize benefits. The other is that because of the significant number of Americans covered under the Social Security system, Congress will fix the deficit without making any changes in future benefits.

There have been attempts to quantify the risk of a future drop in benefits, similar to the calculations by Duffy, Finke, and Blanchett (2021). Elsasser (2020) analyzes this risk by using the example of a healthy 62-year-old female. He considers possible ages of death and the probability of survival at that age, then tests the value of claiming at age 62 and at age 70. In the analysis he applies a 24 percent benefit cut in 2029 and a 24 percent benefit cut in 2035. His conclusion is that the possibility of cuts in benefits due to Social Security insolvency is not enough to justify claiming early. While the current underfunding of the Social Security system remains an important consideration, much of the literature acknowledges that there are better planning strategies than simply claiming Social Security as soon as possible in order to get the benefits before they go away.

Taxes

The federal taxes that apply in retirement, and the order in which benefits are withdrawn, can have a significant impact on the net benefits received by an individual or couple claiming Social Security. Our analysis below factors in a number of these tax and ordering issues, including the IRMAA tax penalty on Medicare premiums. Reichenstein and Meyer (2022) consider coordination of Social Security to create a tax-efficient withdrawal strategy. They discuss the complexity of selecting the most tax-efficient withdrawal strategy in retirement, and the importance of the claimant understanding how their method of creating retirement income will impact Social Security taxation and Medicare costs.

Methodology

We use two case studies to quantify how different Social Security claiming strategies impact a retirement income plan using rolling periods from the U.S. historical market data. Each case study is about individuals who recently retired after celebrating their 62nd birthday in January 2022. For their retirement finances, the priority is to build a financial plan that will cover their spending goals through age 95. In cases where this is feasible, a secondary priority is to maximize the after-tax surplus of wealth for their beneficiaries at age 95. We choose relatively conservative spending strategies so that most simulations will still have remaining investment funds available when reach-ing age 95. In simulations where investment assets deplete prior to age 95, legacy is measured as a “reverse legacy” of the shortfall of funds relative to the spending goals that could not be met.

Study Number 1

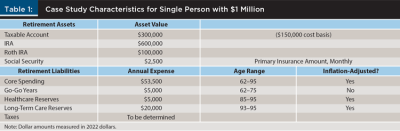

The first case study is for a single individual with $1 million of total investment assets. Details are shown in Table 1. The retirement assets include $300,000 in a taxable brokerage account (with a $150,000 cost basis), $600,000 in a tax-deferred individual retirement account (IRA), and $100,000 in a tax-exempt Roth IRA. In the case studies, we assume the individuals are renters in retirement to avoid the additional complications associated with managing home equity in the retirement plan.

This individual’s Social Security PIA is $2,500 per month ($30,000 per year). This is the annual benefit if claiming at the full retirement age of 67 (using current age 62 dollars). The benefit is $21,000 annually if claiming at 62, and $37,200 annually if claiming at 70.

As for the individual’s retirement liabilities, the projected core retirement expenses equal an infla-tion-adjusted $53,500 throughout retirement. This retiree also seeks to spend an additional $5,000 each year through age 75 that is not inflation-adjusted, to get the most enjoyment out of the go-go retirement years, which Stein (1998) defined as the phase in early retirement when retirees are more active in enjoying travel and leisure activities before slowing down later. This individual also seeks reserves to cover contingencies related to healthcare (an additional inflation-adjusted expenditure of $5,000 between the ages of 85 and 95), and long-term care (an additional inflation-adjusted expenditure of $20,000 between the ages of 93 and 95) to reflect overall expense increases after accounting for a reduction in other expenditures when experiencing a long-term care need. The individual lives in a state with no income tax.

There is also a need to pay federal income taxes—an additional expense that will be included in this analysis beyond these spending goals. We calculate taxes on the portfolio distributions, including qualified dividends, interest, and long-term capital gains from the taxable account, the ordinary income generated from IRA distributions, the precise amount of taxes due on Social Security benefits, any Medicare premium surcharges if modified adjusted gross income exceeds the relevant thresholds, and any potential net investment income surtaxes due. These taxes are calculated based on tax law in early 2022, including the shift to higher tax rates in 2026 that is part of the sunsetting provisions in current law. Tax brackets increase with inflation, though the thresholds for determining taxes on Social Security are not inflation adjusted. We use the required minimum distribution (RMD) life tables introduced in 2022 for calculating RMDs. We also assume the 2022 standard deduction is used unless the additional expenses for the health and long-term care spending exceed 7.5 percent of adjusted gross income by a large enough degree that this amount is greater than the standard deduction.

Investment assets are all held in a balanced fund of stocks and bonds. We consider three different stock allocations for the investments: 25 percent, 50 percent, and 75 percent stocks. Stocks are rep-resented with large-capitalization U.S. stocks, while bonds reflect 10-year constant maturity Treasuries. Stock dividends are assumed to be qualified and receive preferential income tax rates, bond interest is taxed as ordinary income, and we assume that unsold investments do not generate any unrealized capital gains distributions.

The legacy value of assets reflects the after-tax value of investments remaining at age 95. Taxable assets receive a step-up in basis at death, providing their full value for heirs. For tax-deferred assets, we assume that adult children will be beneficiaries, and the SECURE Act requires them to spend down the account within a 10-year window when they may still be in their peak earnings years and face higher tax rates. To reflect this, we assume that remaining tax-deferred assets will be taxed at a 25 percent rate to reduce their legacy value to heirs. Though distributions from inherited IRAs can be amortized over 10 years, we assume a full distribution in the first year as a simplification. Tax-free Roth assets also face the same distribution requirements, but they will not be taxable to heirs, so their full value passes as legacy.

If the entire spending goal cannot be met over the retirement planning horizon, we calculate the spending shortfall as a reverse legacy, reflecting the amount of desired spending that cannot be met. It is the sum of desired spending less the available income sources. When investments deplete, Social Security remains as the only source of income to offset some expenses, and the shortfall reflects the remaining uncovered spending goal. Retirement success is measured as having any investment assets remaining at age 95 such that there were no spending shortfalls for the simulation.

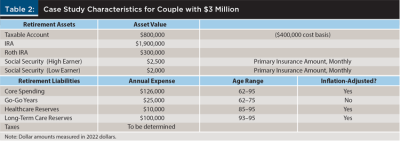

Study Number 2

The second case study is for a couple with $3 million of investment assets. As with the first study, both individuals are age 62 and have just retired. They share the same goal of funding retirement through age 95, with a secondary priority to maximize the after-tax surplus of wealth for their beneficiaries at an assumed age 95 death. Further details are shown in Table 2. The retirement assets include $800,000 in a taxable brokerage account (with a $400,000 cost basis), $1,900,000 in a tax-deferred IRA, and $300,000 in a tax-free Roth IRA. The two spouses have Social Security PIAs of $2,500 per month ($30,000 per year) and $2,000 per month ($24,000 per year). If they both claim at 62, total annual benefits with the early claiming reduction add up to $37,800. At full retirement age (age 67), total benefits are $54,000. And if they both wait to age 70 to file, total benefits increase to $66,960. These amounts are provided in current age 62 dollars, as annual cost-of-living adjustments assumed to match the consumer price index are applied in all cases.

The projected core annual retirement expenses for the couple equal an inflation-adjusted $126,000 throughout retirement. They seek to spend an additional $25,000 per year through age 75 to better enjoy the more active go-go years of their retirement. The couple also seeks reserves to cover contingencies related to healthcare (an additional inflation-adjusted expenditure of $10,000 between the ages of 85 and 95) and long-term care (an additional inflation-adjusted expenditure of $100,000 between the ages of 93 and 95), reflecting a relatively greater concern about out-of-pocket long-term care spending than the first person. They also live in a state with no income tax, but there is a need to pay federal income taxes—an additional expense that will be included in this analysis beyond these mentioned spending goals. Taxes are calculated in the same manner as described with the first case study, and the same three asset allocation choices will be used.

Distributions

Portfolio distributions will include Roth conversions and use a blended strategy that mixes taxable and tax-deferred distributions at first, and then tax-deferred and tax-free distributions later, to provide control over the adjusted gross income (AGI) as a tax-management strategy. The retirees take any required minimum distributions from the tax-deferred account, which begin at age 72. If RMDs and Social Security benefits are less than the desired spending and federal income taxes due, additional withdrawals are then estimated to be taken from the taxable account first until empty, then from the tax-free Roth account until empty, and then from the tax-deferred account until empty.

This is a starting point for distributions. If this distribution ordering leads to less than the targeted level of AGI for managing lifetime taxes, then additional funds are taken from the IRA to offset any Roth IRA distributions and then further convert funds from the IRA to the Roth IRA to generate additional taxable income. Taxes on these additional IRA distributions and conversions are paid through further distributions from the taxable account when possible, or otherwise from the tax-deferred account when the taxable account depletes. Distributions are taken at the start of each year.

This algorithm leads spending strategies to be a blend of taxable and tax-deferred IRA assets while taxable assets remain, and then a blend of IRA and Roth IRA assets. If Social Security benefits and RMDs from the IRA exceed the desired spending level and taxes due in any year, then any surplus is added as new savings to the taxable account. The targeted level of AGI is the median level of AGI that maximizes the after-tax value of wealth at age 95 (checked in $10,000 increments).

Simulations

For the simulations, we use rolling historical periods from U.S. data since 1871. We use the tax laws and Social Security rules as they exist in early 2022. These details have been described, but it is worth emphasizing that the purpose of using historical data is not to shift back in time, but rather to provide a range of possible experiences for stock returns, bond returns, interest rates, and inflation, from the perspective of considering if these historical market outcomes began anew in 2022. For example, the simulated experience starting from 1950 just considers how a retiree in 2022 would fare with different claiming strategies under current tax rules if the retiree experienced the sequence of market outcomes that begin in 1950.

We believe that the advantages of using historical data outweigh their downsides, though Social Security delay strategies may not perform as well with historical data as they could at the present. Interest rates are well below historical averages, which benefits delaying Social Security relative to a higher interest rate environment. Nonetheless, understanding the historical performance of Social Security delay strategies is an important data point when thinking about the long-term financial im-pacts of different Social Security claiming strategies in a broader historical context.

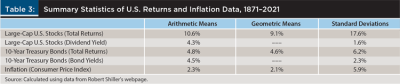

The financial market data are freely available from Robert Shiller’s website (www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.htm). The historical performance is summarized in Table 3. Stocks are represented with large-capitalization U.S. stocks that eventually became the S&P 500. Since 1871, they averaged 10.6 percent returns, with a compounded growth rate over time (geometric mean) of 9.1 percent and volatility of 17.6 percent. The dividend yield on stocks averaged 4.3 percent historically.

Bonds are represented with 10-year constant maturity Treasury bonds. These bonds average 4.8 percent returns historically, with a 6.2 percent volatility. This is a bit higher than the average yield of 4.5 percent, since yields trended lower during the historical period, allowing for a higher average bond return as interest rates decline. These averages are high compared to the present, as the 10-year Treasury was yielding about 1.6 percent at the start of 2022. Inflation averaged 2.3 percent historically with a 5.9 percent volatility.

Results

To investigate the results for different Social Security claiming strategies with these two case studies, we first focus on higher-level summary metrics and then dive deeper into the results for the case using a 50 percent stock allocation.

Study Number 1

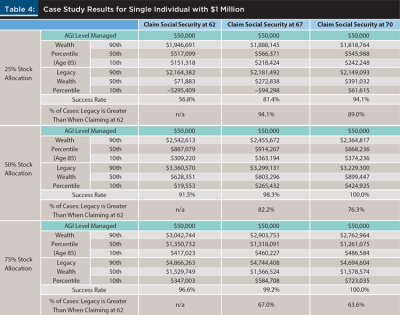

Table 4 provides these results for the single 62-year-old with $1 million of investment assets. This table provides results from the 118 rolling 34-year periods between 1871 and 2021. These retirement simulations require 34 years of data to cover ages 62 through 95, so the most recent of the rolling periods begins in 1988. For each of the three stock allocations and each of the three Social Security claiming strategies, the table shows: (1) the median level of AGI that maximizes the after-tax value of wealth at age 95 (checked in $10,000 increments), (2) remaining real wealth at age 85 (in age 62 dollars) to provide a sense of the strategy’s evolution at around life expectancy, (3) the real legacy wealth at age 95 (in age 62 dollars) at the 90th, 50th, and 10th percentiles, (4) the success rate for the strategy defined as the percentage of cases that the entire spending goal could be met with investment assets remaining at age 95, and (5) the percentage of the historical simulations in which claiming at 67 or 70 allowed for a higher net legacy at the end of retirement than claiming at age 62.

As we increase from a 25 percent stock allocation to 75 percent stocks, we notice several trends. First, the managed level of AGI tends to show slight increases as expected portfolio returns rise. Also, success rates tend to improve with higher stock allocations, as does the range of wealth at age 85 and final wealth at age 95 across the distribution of outcomes. Finally, even with 75 percent stocks, delaying Social Security increases final wealth about two-thirds of the time, and these percentages are even higher with low stock allocations. A more aggressive stock allocation does increase the odds of having an improved retirement outcome, but even with 75 percent stocks, claiming at age 62 only helped in a minority of the outcomes.

The cumulative real Social Security benefits through age 95 is $1.285 million when started at 62, $1.566 million when started at 67, and $1.741 million when started at 70. Breakeven ages for cumulative real benefits happen in one’s early 80s, when delaying begins to provide a larger lifetime amount. Investments must outperform these hurdles to have the early claiming strategy come out ahead over the long planning horizon. Readers may make their own judgements regarding which approach to claiming Social Security makes the most sense in this historical context and for this case study. With these results, it is likely that only individuals with high risk tolerance would even consider claiming earlier for asset maximization purposes.

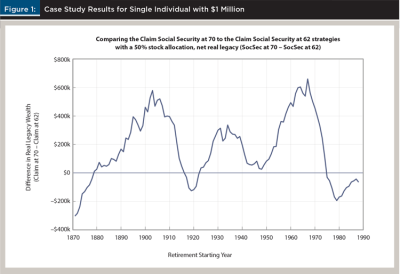

Next, Figure 1 provides a deeper look at the comparison between claiming at age 70 and at age 62 when using a 50 percent stock allocation in retirement. As seen in the previous table, delaying from 62 to 70 provides larger net legacy wealth at age 95 in 76.3 percent of the historical cases. The exceptions for when claiming at 62 paid off include during the 1870s, around 1920, and in the period from the mid-1970s into the 1980s. These were periods in which market returns were strong during the first eight years of retirement when the delay happens, which lays a foundation for additional funds left in the investment portfolio to provide greater growth. Otherwise, much of the historical period shows stronger increases to legacy when delaying benefits to age 70.

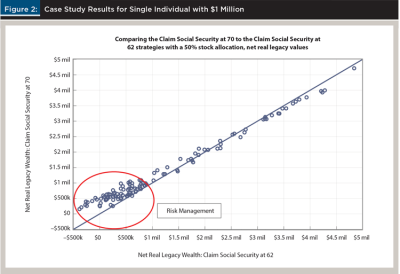

Figure 2 confirms the idea that delaying Social Security works to manage retirement risk. This figure plots the net real legacy wealth for the early-claiming strategy on the horizontal axis, and the net real legacy wealth for the delay strategy on the vertical axis. Not only does this highlight that in all historical cases, the delay strategy avoided a negative legacy, but also that when legacies were otherwise smaller for both strategies because of poor market returns, the delay strategy consistently provided better outcomes. This is demonstrated with all the circled points that are above the diagonal line. Because net legacies are larger with delay when both strategies result in relatively low legacies (the circled outcomes under $1 million), we can see the risk management benefits of delayed claiming. It is only when net legacies are otherwise quite large (beginning around $1.5 million) that the delay strategy starts to fall short. But legacies were still quite large either way; the early claiming strategy only consistently wins after $2.5 million, and the relative differences between the two outcomes are quite small. Risk averse retirees will tend to prefer strategies that provide more protection on the downside, even if that means sacrificing some upside. The figure makes clear that there is risk-management value in spending down other investment assets during the first eight years of retirement to enjoy a permanently higher Social Security benefit after that point.

Though it is reasonable to expect that delaying Social Security may give up some of the upside po-tential if financial markets perform extremely well in retirement, which is the argument sometimes made in favor of claiming early, this figure highlights the low odds for achieving a better outcome for this case study when using a 50 percent stock allocation in retirement. Claiming early can lead to a better outcome, but it is not common and should not be expected.

Study Number 2

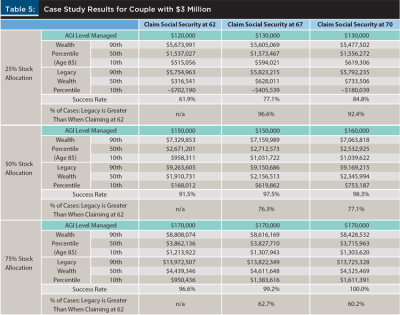

Table 5 continues this analysis with results for the case study with a couple holding $3 million of investment assets at retirement. Qualitatively, the results are quite similar to the first case study, though the AGI management levels and legacy values are generally scaled upward to reflect the greater wealth of this couple. It is still the case that delayed claiming improves success rates and generally supports a larger legacy at the end of retirement. Again, though success rates increase with a higher stock allocation, more exposure to market upside does provide greater opportunity for claiming early to keep more invested to experience these benefits. However, even with 75 percent allocated to stocks, delayed claiming supports greater legacy in more than 60 percent of the historical cases.

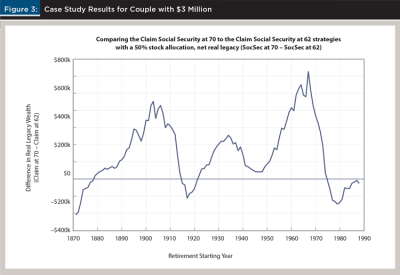

Figure 3 provides a similar analysis comparing the claiming decisions for ages 70 and 62 when using a 50 percent stock allocation. Values above the horizontal line mean that delayed claiming provides a larger legacy, while claiming at 62 comes out ahead for values below the horizontal line. Delayed claiming supports greater legacy wealth in 77.1 percent of the historical cases, with exceptions occurring in the 1870s, 1910s, and the years around 1980. Otherwise, delayed claiming provides a better retirement outcome, and often by a notably larger degree.

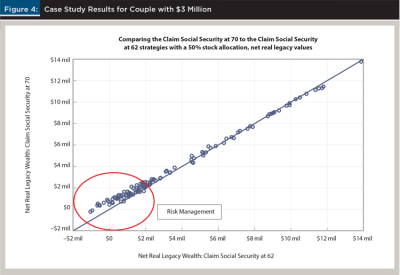

Figure 4 provides the same risk management analysis for this case study. It is again the case that delayed claiming supports larger legacy values in historical cases where overall legacy wealth is on the relatively low side (less than $2 million). When legacy wealth is otherwise high, early claiming may come out ahead, but the relative differences between the two strategies are small. This again points to the risk management advantages of delayed Social Security claiming.

Conclusions

Delaying Social Security can be framed as longevity insurance that helps to support the increasing costs associated with living a long life. It provides inflation-adjusted lifetime benefits for a retiree and a surviving spouse, and these monthly benefits will be 77 percent larger in inflation-adjusted terms for those who claim at 70 instead of at 62. The actuarial factors supporting that 77 percent increase were designed in 1983 when longevity was shorter and interest rates were higher, suggesting at the very least that delaying Social Security and meanwhile spending down other fixed-income assets has a better than even chance of improving the retirement outcome (Pfau 2021).

But sometimes this insurance value is questioned, with the idea being that an early claiming decision will provide an opportunity for investments to grow and provide better retirement outcomes. We have analyzed this matter with historical data.

Simple extrapolations about suggesting that claiming Social Security early and investing the benefits to earn historical stock market returns miss several important points about retirement income. First, many retirees will not otherwise be investing anywhere near this aggressively in retirement. For lower stock allocations, the expected portfolio return would also be less. Second, such analysis must frame the problem within an entire retirement balance sheet that includes not just financial assets but the need to fund liabilities with those assets. The funding constraint creates additional risk that returns must materialize within shorter periods near the retirement date. A reverse legacy potentially risks the retiree having insufficient funds for living expenses.

This uncertain quest for upside growth means giving up a valuable, lifelong, inflation-adjusted in-come stream. To make risks relatively comparable, the appropriate investment would be a Treasury Inflation-Protected Security (TIPS) that provides the same inflation protection and government backing as Social Security. TIPS yields are not high enough to benefit early claiming for those living to life expectancies. To generate the returns needed to beat the benefit of delaying Social Security, there would need to be a high tolerance for risk and an aggressive asset allocation, not to mention plenty of discretionary wealth. People tend to be overconfident about their investing prowess, making it easy to fall into a behavioral trap. We do find evidence using the historical data that it is uncommon for investment returns to beat the implied benefit of delaying Social Security for long-lived retirees even with relatively aggressive asset allocation strategies.

Two important details to consider for subsequent research include, first, whether the increased present value of inflation-adjusted lifetime income that accompanies Social Security delay would allow the retiree to feel more comfortable with using a higher stock allocation with the investment portfolio. If one is comfortable thinking about Social Security as a fixed-income asset, then delaying Social Security provides a higher present value of fixed income on the household balance sheet. Delaying Social Security can increase risk capacity and reduce risk exposure for the household, which could justify a higher stock allocation than otherwise. A willingness to invest more aggressively alongside Social Security delay could be an alternative way to achieve more market growth for those who are comfortable taking on greater risk for investment upside.

In addition, this research did not incorporate a Social Security delay bridge when delaying Social Security past age 62. This increases risks related to a market downturn because the distribution rate from the investment portfolio is temporarily higher when delaying Social Security. To reduce this risk, retirees may seek to carve out a laddered bond portfolio or use some related approach such as a period-certain single-premium fixed annuity to build a floor of income to match the missing Social Security benefits so that greater short-term risks are not taken with the retirement plan.

Citation

Pfau, Wade D., and Steve Parrish. 2023. “Which Social Security Claiming Strategy Generates the Highest Legacy Value?” Journal of Financial Planning 36 (1): 68–84.

References

Duffy, Sophia, Michael Finke, and David Blanchett. 2021. “The Value of Delayed Social Security Claiming for Higher-income Women.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals (September).

Elsasser, Joe. 2020, June 23. “Should You Claim Social Security Early Because of COVID-19?” The Street: Retirement Daily. www.thestreet.com/retirement-daily/social-security-medicare/should-you-claim-social-security-early-because-of-covid-19.

Levine, Jeffrey. 2022, March 14. “Getting Clients Comfortable Delaying Social Security with Reversible Delays.” Financial Planning. www.financial-planning.com/news/getting-clients-comfortable-delaying-social-security-with-reversible-delays.

Parrish, Steve. 2020. “Dealing with the Insecurity of Social Security.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals (November).

Pfau, Wade D. 2016, June 13. “The Advantages of Monte Carlo Simulations.” Forbes.

Pfau, Wade D. 2021. Retirement Planning Guidebook: Navigating the Important Decisions for Retirement Success. Vienna, VA: Retirement Researcher Media.

Reichenstein, William, and William Meyer. 2022. “Social Security Coordination to Create a Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategy.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals (March).

Social Security Administration Board of Trustees. 2022. Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance (OASDI) Trust Funds. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Stein, Michael. 1998. The Prosperous Retirement: Guide to the New Reality. Emstco Press.