Journal of Financial Planning: July 2022

Executive Summary

- Financial planners collect vast amounts of data from individual clients to determine appropriate investment strategies. It is important to be able to accurately categorize appropriate financial and investment recommendations to ensure regulatory compliance, client acceptance, and financial planning strategy adherence, all of which foster trust, understanding, and further validation of the professional relationship.

- This paper describes how the marital status of a financial decision-maker is associated with their financial risk tolerance. This paper makes conclusions with respect to whether a client’s marital status needs exclusive consideration in the context of financial planning and the investment management process.

- Using data from 1,174 financial decision-makers, it was determined that marital status is not uniformly associated with financial risk tolerance.

- Financial knowledge emerged from the analyses as the most important descriptor of financial risk tolerance across genders. Additionally, older respondents were found to be less willing to take a risk.

John E. Grable, Ph.D., holds an Athletic Association Endowed Professorship at the University of Georgia where he conducts research and teaches financial planning. Dr. Grable is best known for his work related to financial risk tolerance assessment and behavioral financial planning. He serves as the director of the Financial Planning Performance Laboratory. Email him HERE.

Eun Jin (EJ) Kwak is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Financial Planning, Housing and Consumer Economics at the University of Georgia. She holds a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in business management with an emphasis on big data analysis. Prior to entering the academic profession, she worked at J.P. Morgan and UBS as a financial analyst. Ms. Kwak is the co-author of several peer-reviewed research papers. Her research focuses on financial risk tolerance/aversion assessment, household finance, behavioral financial planning, and machine learning. Email here HERE.

Pan-Ju Chen is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Financial Planning, Housing and Consumer Economics at the University of Georgia. Her research interests include financial well-being, social comparisons, and scarcity. Email here HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions

Financial planners are tasked with collecting relevant data from clients and dealing with a variety of client issues on a daily basis. Demographic information (e.g., age, gender, and marital status) collected from clients is presumed to be useful when customizing financial planning recommendations. The use of client demographic and attitudinal data is particularly important when developing investment recommendations in a way that matches a client’s willingness to take financial risks (Cavezzali and Rigoni 2012). Marital status is one demographic variable that is sometimes assumed to be related to risk tolerance. Whether an association actually exists has not been thoroughly examined in the literature (Kannadhasan 2015).

A lack of clarity in the literature related to the association between marital status and financial risk tolerance can lead to the inappropriate use of marital status classifications as modeling inputs. Consider the following situation that occurs on occasion. In this scenario, an investor engages the services of a financial planner to manage a portion of the investor’s portfolio. During the data-gathering phase of the investment management process, the financial planner collects background details from and about the investor. The financial planner learns, for instance, that the investor is 55 years of age and employed full-time. In addition to other individual and household characteristics (e.g., the investor is female), the financial planner also learns that the investor is single and has never been married. A question arises; namely, is the marital status of this investor a relevant factor in the investment management process? Stated another way, should the marital status of the investor be weighed by the financial planner when allocating monies between risk-free and risky assets in a way that aligns with the investor’s financial risk tolerance?

Although the financial risk-tolerance and financial planning literature provide guidance in identifying meaningful associations between and among investor demographic characteristics, financial risk tolerance, and financial risk-taking, this literature is relatively silent in answering the financial planner’s question. As will be discussed later in this paper, some researchers believe that marital status is a relevant data point in the investment management process. Sung and Hanna (1996), for example, noted in their study that marital status was an important factor that explained some differences in risk tolerance across households. In another study, Xiao (1996) reported that stock ownership was positively associated with being married. Others have argued that marital status is not particularly relevant. DeVaney, Sharpe, Kratzer, and Su (1997), for instance, showed in their study that marital status was not significantly associated with self-employed workers’ retirement savings. Thompson, Feng, Reesor, and Grace (2021) echoed this conclusion by arguing that marital status has limited usefulness in explaining investors’ behaviors. It is worth noting that little has changed since Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie (2003) summarized the literature this way: “The relationship between marital status and risk tolerance is an issue that remains unresolved” (p. 483). The purpose of this paper is to fill this gap in the literature by specifically evaluating the association between financial risk tolerance and categories of marital status. If marital status is a relevant investment management characteristic, one should expect to see categories of marital status significantly associated with risk tolerance even after controlling for other individual and household characteristics.

Background

A client’s marital status (e.g., single, married, divorced) is often assessed during the data-intake phase of the investment management and financial planning process. Knowledge of a client’s marital status plays a role in recommendations related to asset titling and other estate planning issues. However, there is little consensus regarding the role marital status should play in describing or guiding the investment management process (Grable and Joo 2004; Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie 2004; Koekemoer 2018; Wong 2011; Yang 2004). To date, few studies have been undertaken to establish a link between marital status and risk tolerance. If an association does exist, data should support direct associations between risk tolerance and being married, single, separated, divorced, or widowed. If, for example, data show that being married is related to exhibiting higher levels of risk tolerance, this should provide a directional input for financial planners when providing investment advice to married clients—a married client ought to be more willing, in this scenario, to take additional financial risk in their portfolio.

It is important to note that it is difficult to conclusively state whether a client’s risk tolerance—the degree to which a client is willing to take a risk when the decision outcome is both unknown and potentially negative (Nobre and Grable 2015)—is related to a client’s marital status (McInish 1982). Findings reported in the literature over the past several decades are often contradictory. For example, over a decade ago, Anbar and Eker (2010) stated that there is no relationship between marital status and financial risk tolerance. Contrary to this conclusion, others have shown that being married is related to increased levels of risk tolerance (e.g., Grable and Joo 2004; Koekemoer 2018). It is worth remembering that for every paper showing a relationship between being married and an increased willingness to take a financial risk, others can be found that argue those who are single should be more willing to take a financial risk (e.g., Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie 2004; Roszkowski, Davey, and Grable 2005; Wong 2011).

The primary propositions underlying a potential association between financial risk tolerance and marital status are that either (a) those who are single should be more willing to take a risk because decision outcomes are limited to the decision-maker1 or (b) those who are married should be more willing to take a risk because they have greater household financial capacity to deal with potential losses arising from declines in investment asset values. There are also other assumed benefits associated with marriage that might lead to an enhanced willingness to take financial risks, including greater household income, shared financial literacy, complementary psychological traits, and shared goals.

Some researchers have argued that rather than view marital status as a single covariate, marital status should be combined with gender to obtain a more complete picture of any meaningful associations. For example, Yao, Gutter, and Hanna (2005) observed differences in risk tolerance based on gender–marital status combinations. They found in their study that risk tolerance was highest for single males and married males. One shortcoming with the Yao, Gutter, and Hanna study is that they did not test for differences between being married and being divorced, widowed, or separated.

Reports in the literature of associations between financial risk tolerance and marital status are often made as an afterthought. Marital status, as an input into empirical models, is typically included as a control variable, particularly when individual and household characteristics, such as income and education, are being evaluated. This places financial planners in a quandary. Should they use a client’s marital status as an input—either in a formal model or as an element of professional judgment—when making investment recommendations? The purpose of this paper is to address this question by describing how the marital status of a financial decision-maker is associated with the decision-maker’s level of accepted risk tolerance. The paper makes conclusions with respect to whether a financial decision-maker’s marital status needs exclusive consideration in the investment management process. The following discussion reviews the data and methods used to address the purpose of the study. This is followed by a report of findings and a discussion of results.

Methods

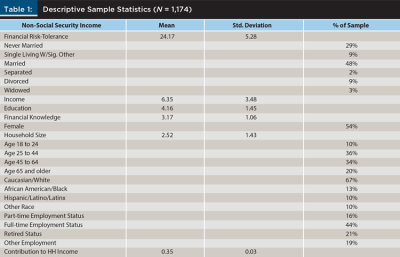

Data were collected in 2020 using two cross-sectional surveys, one administered in March and the other in October. Data were gathered using Qualtrics questionnaires that were distributed to Dynata panels. The regression models (described below) were estimated using data from 1,174 respondents. Those participating in the surveys received a modest financial incentive. Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the study respondents. The following discussion reviews how the variables used in this study were coded.

Marital Status

A respondent’s marital status at the time the survey was completed was assessed using the following categories: (a) never married, (b) single and living with a significant other (SLWSO), (c) married, (d) separated, (e) divorced, and (f) widowed. Each category was coded dichotomously as 1 if a respondent indicated a particular marital status category, otherwise 0. The largest proportion of respondents were married; this category was used as the reference group in the regression analyses.

Financial Risk Tolerance

The Grable and Lytton (1999) financial risk-tolerance propensity scale was used as a proxy for a respondent’s willingness to take a financial risk when the outcome of the risky decision is both uncertain and potentially negative. The scale, which consists of 13 multiple-choice questions that are summed to create a score ranging from 13 to 47, has been widely used as a research instrument in studies designed to evaluate risk-taking attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Beer and Wellman 2021; Chung and Au 2022; Kuzniak et al. 2015; Lucarelli, Ottaviani, and Vandone 2011; Rabbani et al. 2017; Thanki and Baser 2021; Uckun and Dal 2021). Higher scores on the scale are indicative of an increased willingness to take financial risks. The scale has shown acceptable levels of validity (e.g., scores are known to be positively associated with more aggressive investment choices) and reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha ranges from .70 to over .80, with higher reliability estimates reported for older financial decision-makers) (see Kuzniak et al. 2015) across previous studies. In this study, respondent scores ranged from 13 to 39 (M = 24.17, SD = 5.28). Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to be .76, which was deemed acceptably strong (Nunnally and Bernstein 1994).

Covariates

The following variables were used in the analyses as covariates. The gender of respondents was assessed by asking each respondent to self-identify as male, female, non-binary, or other. No one indicated non-binary or other. Males were coded 1, whereas females were coded 2. Personal income was measured using a 12-point ordinal scale with 1 indicating income less than $10,000 and 12 indicating more than $150,000. Formal attained education was assessed using an ordinal scale ranging from 1 indicating some high school or less to 6 indicating graduate or professional degree. Subjective financial knowledge was evaluated by asking, “How knowledgeable are you about personal finance topics?” Respondents were asked to indicate their knowledge from the following five categories: (1) not knowledgeable at all, (2) slightly knowledgeable, (3) moderately knowledgeable, (4) very knowledgeable, and (5) extremely knowledgeable. Household size was assessed by asking, “How many people live in your household?” Respondents were grouped by age into the following categories (a) 18 to 24, (b) 25 to 44, (c) 45 to 64, and (d) 65 and older. The “18 to 24” group was used as the reference category in the analyses. Self-classified race/ethnicity was assessed by asking each respondent to self-report whether they affiliated as (a) Caucasian/White, (b) African American/Black, (c) Hispanic/Latino/Latinx, (d) Native American, (e) Asian or Pacific Islander, or (f) other. Responses were then coded dichotomously so that group membership was coded 1, otherwise 0. The Caucasian/White category was used as the reference category in the regression analyses. Employment status was assessed using the following four employment categories, which were dummy coded: (a) part-time employment status, (b) full-time employment status, (c) retired status, and (d) other employment status. The “other employment status” was used as the reference category in the regression analyses. Finally, each respondent’s contribution to their household’s income was estimated by comparing reports of personal income to total household income. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for each of the variables used in the study.

Marital Status by Gender Classifications

The following six marital status by gender interaction terms were created to determine if the relationship between marital status and financial risk tolerance was moderated by gender: (a) gender x never married, (b) gender x married, (c) gender x SLWSO, (d) gender x separated, (e) gender x divorced, and (f) gender x widowed. The gender x married variable was used as the reference category in the regressions.

Data Analysis Methods

A hierarchical OLS regression, using five blocks of variables, was used to determine the effects of marital status, gender, and marital status interacted with gender on financial risk tolerance. The first block used in these estimations included the marital status variables (the married classification was used as the reference category). Gender was included in the second block. To account for possible covariation in marital status and gender, the interaction terms were included in the third block of the regression analysis (gender x married was used as the reference category). Personal income, educational status, and financial knowledge were entered in the fourth block. The remaining covariates were included in the final block. This regression was followed by two OLS regressions to determine the degree to which financial risk tolerance was associated with marital status among female and male respondents separately.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive sample statistics. Financial risk tolerance fell in the mid-range of the scale. The largest proportion of respondents (i.e., 48 percent) were married at the time of survey completion. Those who were single comprised the next largest percentage (i.e., 38 percent). The sample was slightly overweighted by female respondents (i.e., 54 percent). Personal income ranged between $50,000 and $59,999. The modal formal attained education category was a bachelor’s degree. Self-assessed financial knowledge was in the mid-range of the scale. The correlation between education and financial knowledge was positive (r = .17) but not high enough to prompt concerns over multicollinearity. The average household size was 2.52 persons. The majority of respondents were aged 45 years or older, Caucasian/White, and either employed full-time or retired. On average, respondents contributed approximately 35 percent of their income to their household’s cash flow situation.

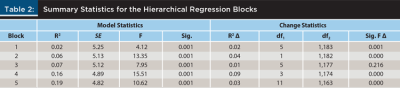

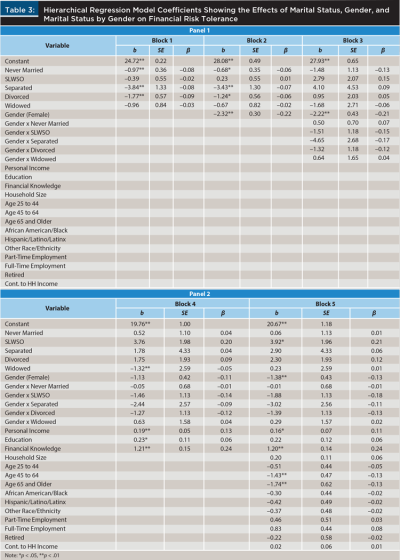

Tables 2 and 3 show the results from the hierarchical OLS regression. The model was developed to determine whether marital status, gender, and/or interactions between gender and marital status, holding other factors constant, were associated with a respondent’s financial risk tolerance. The overall model was statistically significant, F11,1163 = 10.62, p < .001, explaining approximately 19 percent of the variance in risk-tolerance scores. Table 2 shows the summary change statistics for each step in the hierarchical regression. In Blocks 1 and 2, the risk tolerance of those who reported being never married, separated, and divorced was lower than that of married respondents. In Block 3, when the interaction terms were added, the statistical significance of marital status in describing financial risk tolerance was reduced.2

Once the initial results from the regression were confirmed, the other variables in the model were examined. In the final analysis (i.e., Block 5), respondents who indicated being single and living with a significant other, compared to a married respondent, were found to exhibit more risk tolerance. None of the other marital status classification or interaction terms were significant. Gender, rather than marital status, emerged as a more important descriptor. Females, across the blocks, were found to be less willing to take financial risks compared to males. Other variables of significance in the final block of the regression were personal income and financial knowledge, which were positively associated with financial risk tolerance, and being 45 years of age or older, which was associated with lower financial risk tolerance.

Findings from the hierarchical regression analysis (Table 3) provide evidence that in general, marital status is not a particularly useful indicator of financial risk tolerance. Other than being single and living with a significant other, classifications of marital status were not useful in portraying a respondent’s willingness to take financial risks. Gender, however, was important in this regard. Females, compared to males, were observed to be less risk tolerant. While this finding is interesting, it provides only a partial answer to the question that was asked at the outset of this paper; that is, is the marital status of an investor a relevant factor to consider as an input into the investment management process? The coefficients shown in Table 3 are not particularly useful if a financial planner’s clients are primarily females or males. A logical next question then is to ask to what extent do classifications of marital status describe differences in financial risk tolerance among females and males separately?

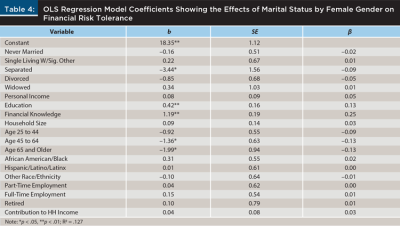

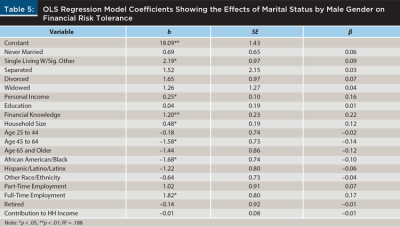

Two OLS regressions were estimated to answer this question. The first regression (Table 4) was run using data from females (n = 634). The second regression (Table 5) was run using data from males (n = 540). The married classification was used as the reference category in both regression models.

The female-only OLS regression model shown in Table 4 was statistically significant, F19,615 = 4.713, p < .001. The model explained approximately 13 percent of the variance in financial risk-tolerance scores for females. Compared to married females, females who were separated at the time of survey completion reported a lower risk tolerance. No other marital status differences in financial risk tolerance were noted. Other variables of importance included education and financial knowledge, both of which were found to be positively associated with risk tolerance. The financial risk tolerance of those older than age 45 was observed to be lower than the risk tolerance of younger female respondents.

Table 5 shows the results for the male-only regression. The model was statistically significant, F19,536 = 4.546, p < .001. The model explained approximately 19 percent of the variance in risk-tolerance scores for male respondents. Only one marital status variable was significant. Compared to married males, males who were single and living with a significant other were found to be more risk tolerant. Personal income, financial knowledge, household size, and full-time employment status were observed to be positively associated with financial risk tolerance, whereas being between the ages of 45 and 64 and self-identifying as Black/African American (compared to White/Caucasian) were found to be negatively associated with risk tolerance for males.

Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the association between financial risk tolerance and categories of marital status to determine if marital status is a characteristic that financial planners (and other financial service professionals) who provide investment recommendations should incorporate into models of investment advice. The findings from this study help fill the existing gap in the financial risk-tolerance literature by showing that, in general, marital status is not uniformly associated with a financial decision-maker’s willingness to take financial risks.

No direct evidence was found to support the working proposition posited by some that those who are single should be more willing to take a financial risk. Additionally, no evidence was noted for the proposition that those who are married should exhibit more risk tolerance. While it is true that in the unconstrained full-sample model, those who reported being SLWSO exhibited risk-tolerance scores that were greater than scores for married respondents, being otherwise unmarried (i.e., single but not in a meaningful romantic relationship) was not significant in describing financial risk tolerance. Across all models, females exhibited less risk tolerance than males. Results from the tests indicate that given the choice to use either marital status or gender as an indicator of the degree to which someone is willing to take financial risks, gender provides a better description of financial risk tolerance.

Marital status differences between females and males were noted when separate models were estimated. Compared to married females, females who were separated at the time of survey completion reported being less willing to take financial risks. In the male-only model, males who were living with a significant other exhibited greater risk tolerance compared to married males. Among female respondents, education and financial knowledge were positively associated with financial risk tolerance. Financial knowledge was likewise significant in the male-only model; however, education was not significant. Instead, personal income, household size, and full-time employment status were significant. Across both the female and male estimations, being between the ages of 45 and 64 was found to be negatively associated with risk tolerance. For females, but not males, those age 65 or older were also less risk-tolerant. For males, being Black/African American was found to be associated with decreased risk tolerance.

Conclusion

Readers were asked, at the outset of this paper, to imagine the following scenario: A financial planner was designing an appropriate asset allocation framework for an investor. During the data-gathering phase of the investment management process, the financial planner obtained information about the investor. The financial planner learned that the female investor was 55 years of age, employed full-time, and had never been married. Given this information, readers were asked to determine the degree to which the investor’s marital status should be considered a relevant factor in the investment management process. Results from this study suggest that while a useful data input into general financial planning models, marital status, as a single variable input, should not be used independently in the investment management process. In this study, marital status was generally not statistically associated with risk tolerance, which is itself an important investment management data input. Other investor characteristics were found to be more important, including gender, income, financial knowledge, and age.

There are times, however, when a financial planner’s clientele may be primarily females or males. In these situations, it is important to note that the role of marital status in describing financial risk tolerance likely differs between females and males. Compared to married females, for example, females who are separated would be predicted to report lower levels of financial risk tolerance. This indicates that the riskiness of an investment recommendation for a separated female ought to be different than a recommendation for a married female who shares the same demographic profile. Developing an investment recommendation for two similar males, one who is married and one who is SLWSO, should likewise be different. The SLWSO male would be predicted to exhibit a higher degree of financial risk tolerance, holding other factors constant.

Two commonalities unite females and males, neither of which is a marital status classification. Financial knowledge emerged from the analyses as the most important descriptor of financial risk tolerance across genders. Those with more financial knowledge reported a higher willingness to take a financial risk. The second commonality is age. Older respondents were less willing to take a risk.

When viewed holistically, results from this study suggest the following. First, females tend to exhibit lower levels of financial risk tolerance. This is true across categories of marital status. Second, other variables are more useful in describing financial risk tolerance. Generally, financial knowledge and age provide better insights into a person’s willingness to take a risk. As such, rather than evaluate marital status alone when building investment and financial planning models, financial planners may be better served by evaluating other individual and household characteristics. Third, among females, education is also a useful descriptor of financial risk tolerance, with those who report higher levels of attained education being predicted to exhibit a higher tolerance for financial risk. Finally, among males, income, employment status, and household size are useful descriptors of financial risk tolerance. Specifically, males from larger households who are employed on a full-time basis with more income are predicted to be more willing to take a risk.

The answer to the scenario question presented at the outset of this paper is this: Marital status does not appear to be a particularly useful variable in describing financial risk tolerance, and, as such, marital status may not be a particularly useful input into investment planning models. Given the case scenario, the gender of the investor turns out to be important. In general, females tend to be less risk tolerant compared to males. If a financial planner’s clientele consists primarily of females, then identifying separated clients may be useful. If a financial planner’s clientele is mainly males, then recognizing those who are SLWSO may be a useful procedure. For other financial planners, the importance of marital status becomes less valuable. While a client’s marital status should be evaluated as an element of the financial planning process, a financial planner need not be overly concerned with incorporating the marital status of a client into investment management models if the concern is that the marital status of a married, never married, separated, or divorced client might influence the client’s willingness to take a financial risk.

Citation

Grable, John E., Eun Jin Kwak, and Pan-Ju Chen. 2022. “An Evaluation of the Association Between Marital Status and Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (7): 84–96.

Endnotes

- The reverse of this is those who are married should be less risk tolerant because losses resulting from a decision may cause negative outcomes for others in their household.

- Given the decline in the significance of the marital status variables, two robustness tests were conducted. For the first test, marital status was recoded as 1 = married, otherwise 0. A new interaction marital term with gender was calculated. These new variables were included in a replication of the hierarchical regression. In Block 1, those who were married did exhibit more risk tolerance than others. However, when the interaction term was added, neither variable was statistically significant. In the second test, 12 dichotomously coded variables were created to represent gender-specific marital classifications (e.g., female-married, male-divorced, etc.). These variables were then used in an OLS regression using male-married as the reference category. Results from the test were compared to the first and second blocks from the hierarchical regression. The results showed that gender, rather than marital status, explained nearly all of the variation in financial risk-tolerance scores. The combination of the hierarchical regression and the two robustness tests provided evidence that being single or married did not, in this study, directly describe someone’s financial risk tolerance.

References

Anbar, Adem, and Melek Eker. 2010. “An Empirical Investigation for Determining of the Relation Between Personal Financial Risk Tolerance and Demographic Characteristic.” Ege Akademik Bakis Dergisi 10: 503–522.

Beer, Francisca M., and Joseph D. Wellman. 2021. “Implication of Stigmatization on Investors Financial Risk Tolerance: The Case of Gay Men.” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2021.100513.

Cavezzali, Elisa, and Ugo Rigoni. 2012. “Know Your Client! Investor Profile and Tailor Made Asset Allocation Recommendations.” Journal of Financial Research 35: 137–158.

Chung, Wee K., and Wing T. Au. 2022. “Risk Tolerance Profiling Measure: Testing its Reliability and Validities.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 32 (2). www.afcpe.org/news-and-publications/journal-of-financial-counseling-and-planning/volume-32-2/risk-tolerance-profiling-measure-testing-its-reliability-and-validities/.

DeVaney, Sharon A., Deanna L. Sharpe, Connie Y. Kratzer, and Ya-Ping Su. 1998. “Retirement Preparation of the Nonfarm Self-Employed.” Financial Counseling and Planning 9 (1): 53–59.

Grable, John E., and So-hyun Joo. 2004. “Environmental and Biopsychosocial Factors Associated with Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 15 (1): 73–82.

Grable, John E., and Ruth H. Lytton. 1999. “Financial Risk Tolerance Revisited: The Development of a Risk Assessment Instrument.” Financial Services Review 8: 163–181.

Hallahan, Terrence, Robert Faff, and Michael McKenzie. 2003. “An Exploratory Investigation of the Relation Between Risk Tolerance Scores and Demographic Characteristics.” Journal of Multinational Financial Management 13: 483–502.

Hallahan, Terrence, Robert Faff, and Michael McKenzie. 2004. “An Empirical Investigation of Personal Financial Risk Tolerance.” Financial Services Review 13: 57–78.

Kannadhasan, Manoharan. 2015. “Retail Investors’ Financial Risk Tolerance and Their Risk-Taking Behaviour: The Role of Demographics as Differentiating and Classifying Factors.” IIMB Management Review 27: 175–184.

Koekemoer, Zandri. 2018. “The Influence of Demographic Factors on Risk Tolerance for South African Investors.” Proceedings of the International Academic Conferences, 6408640, International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences.

Kuzniak, Stephen, Abed Rabbani, Wookjae Heo, Jorge Ruiz-Menjivar, and John E. Grable. 2015. “The Grable and Lytton Risk Tolerance Scale: A 15-year Retrospective.” Financial Services Review 24: 177–192.

Lucarelli, Caterina, Cristina Ottaviani, and Daniela Vandone. 2011. “The Layout of the Empirical Analysis.” In Risk Tolerance in Financial Decision Making. Edited by C. Lucarelli and G. Brighetti. Palgrave MacMillan: 153–180

McInish, Thomas H. 1982. “Individual Investors and Risk-taking.” Journal of Economic Psychology 2: 125–136.

Nobre, Liana H. N., and John E. Grable. 2015. “The Role of Risk Profiles and Risk Tolerance in Shaping Client Decisions.” Journal of Financial Service Professionals 69 (3): 18–21.

Nunnally, Jum C., and Ira H. Bernstein. 1994. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rabbani, Abed G., John E. Grable, Wookjae Heo, Liana Nobre, and Stephen Kuzniak. 2017. “Stock Market Volatility and Changes in Financial Risk Tolerance During the Great Recession.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 28 (1): 140–154.

Roszkowski, Michael J., Geoff Davey, and John E. Grable. 2005. “Insights from Psychology and Psychometrics on Measuring Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Financial Planning 18 (4): 68–76.

Sung, Jaimie, and Sherman D Hanna. 1996. “Factors Related to Risk Tolerance.” Financial Counseling and Planning 7 (1): 11–20.

Thanki, Heena, and Narayan Baser. 2021. “Determinants of Financial Risk Tolerance (FRT): An Empirical Investigation.” The Journal of Wealth Management 24 (2). https://doi.org/10.3905/jwm.2021.1.144.

Thompson, John R. J., Longlong Feng, R. Mark Reesor, and Chuck Grace. 2021. “Know Your Clients’ Behaviours: A Cluster Analysis of Financial Transactions.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14 (2): 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14020050.

Uckun, Nurullah, and Lokman Dal. 2021. “Financial Risk Tolerance in Cryptocurrency Investors.” Muhasebe ve Finansman Dergisi 89. DOI: 10.25095/mufad.852118.

Wong, Alan. 2011. “Financial Risk Tolerance and Selected Demographic Factors: A Comparative Study in 3 Countries.” Global Journal of Finance and Banking Issues 5 (5): 1–12.

Yang, Yali. 2004. “Characteristics of Risk Preferences: Revelations from Grable and Lytton’s 13-item Questionnaire.” Journal of Personal Finance 3 (3): 20–40.

Yao, Rui, Michael S. Gutter, and Sherman D. Hanna. 2005. “The Financial Risk Tolerance of Blacks, Hispanics and Whites.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 16 (1): 51–62.

Xiao, Jing Jian. 1996. “Effects of Family Income and Life Cycle Stages on Financial Asset Ownership.” Financial Counseling and Planning 7 (1): 21–30.