Journal of Financial Planning: June 2022

Issues of Financial Services Review are eligible for CE credit. Visit https://fpalearning.onefpa.org.

Editor’s note: This is an extended abstract of a paper that was originally published in Financial Services Review, co-published by the Academy of Financial Services and Financial Planning Association. Visit www.financialplanningassociation.org/learning/publications/financial-services-review to read the original paper in Vol. 29, No. 2.

Note: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

Life insurance is primarily designed to protect the insured against the possibility of losing an income stream, such as the premature death of the family breadwinner (Thoyts 2010). Despite the primary purposes, term life insurance and cash value life insurance have some notable differences: Term life insurance is designed to provide a pure death benefit with a relatively cheaper insurance premium (Gitman, Joehnk, and Billingsley 2014) while cash value life insurance provides a savings element (cash value) and a death benefit (Rejda and McNamara 2016) with a relatively higher insurance premium.

The choice between term life insurance and cash value life insurance depends on consumers’ financial needs and other life situations (Gitman, Joehnk, and Billingsley 2014; Grable 2016). The decision regarding which life insurance policy is the best option is still in question for many consumers, and it is debatable even among financial practitioners as to who really needs which type of life insurance.

The question is not likely to be easily answered when factors come into play beyond traditional demographic characteristics related to life cycle and expected demand. The psychological characteristics of such purchases, including feelings of comfort and recognition, as well as the functional characteristics of life insurance purchases, such as maintaining or improving financial security, can lead to the purchase decisions (Grable and Goetz 2017). Therefore, if financial planners depend only on the demographic and functional characteristics of the purchases, consumers’ needs might not be fully fulfilled.

It is important to better estimate the effect of consumers’ psychological characteristics on demand for life insurance purchases to increase the adequacy of the suggestions and relevance to consumers’ life situations. To include such possibilities, this study examined the role of psychological factors in addition to demographic traits of consumers in the demand for life insurance by ownership patterns.

The Role of Psychographic Factors in the Ownership of Life Insurance

The primary goal of this study is to incorporate the role of psychographic factors in the ownership of life insurance through the use of an online consumer survey. Specifically, this study distinguished the dependent variable (ownership of life insurance) into four categories: (a) none of either term life insurance or cash value life insurance; (b) term life insurance only; (c) cash value life insurance only; and (d) both types of life insurance.

Three aspects of explanatory factors of life insurance ownership were assessed: (a) financial status characteristics include household net balance, the ownership of emergency funds, financial risk tolerance, and subjective financial knowledge; (b) demographic characteristics include the gender, household income, the work status, the number of children, education, age, race, and the marital status, as well as the perceived health condition; and (c) psychological characteristics include locus of control, financial satisfaction, financial self-efficacy, and life satisfaction.

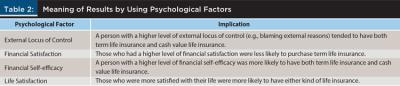

In particular, the first component of the psychological characteristics was locus of control, which was defined as the concept of a person’s perceived controllability of a situation (Rotter 1966). The study used the external locus of control, which denotes that any outcomes took place because of external reasons, such as fate and luck, rather than an attitude toward lifetime consequences that occurred because of a person’s own actions, which is the internal locus of control (Cobb-Clark, Kassenboehmer, and Sinning 2016). Second, financial satisfaction indicates a perceived assessment of one’s own financial situation (Xiao and O’Neill 2018). Third, financial self-efficacy is defined as “one’s sense of being prepared and able to handle financial responsibility” (Montalto, Phillips, McDaniel, and Baker 2019, p. 15). Finally, life satisfaction is a cognitive judgment regarding a person’s own quality of life (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin 1985). All these psychological factors were known to be associated with financial behavior and decision making (Asebedo and Seay 2018; Cobb-Clark, Kassenboehmer, and Sinning 2016; Farrell, Fry, and Risse 2016; Heo, Lee, and Park 2020; Montalto, Phillips, McDaniel, and Baker 2019; Nowicki et al. 2018; Park, Lee, and Heo 2020).

Findings

Table 1 displays the results from the four logistic regression analyses. Financial status characteristics were partially associated with having life insurance. Findings indicated that (a) those with negative net balances were less likely to have any of either term life insurance and cash value life insurance; (b) those who have an emergency fund were more likely to have both term life insurance and cash value life insurance together; (c) those who had a higher level of subjective financial knowledge were less likely to have no life insurance and were also more likely to have both types of insurance; and (d) those who had a higher level of financial risk tolerance tended to be less likely to have term life insurance. Demographic characteristics also showed association with the ownership by type of life insurance. Some variables were model-specific: (a) females showed a negatively significant association only with cash value life insurance; (b) the highest level of education and good health status were positively associated with ownership of cash-value life insurance; (c) the number of children in a family showed a positive association with the ownership of both types of life insurance; (d) the married or coupled respondents were less likely to have no life insurance at all; and (e) older respondents were less likely to have no life insurance.

The psychological characteristics were also partially associated with the ownership of life insurance. First, the locus of control showed a negative association with non-ownership of any term life insurance or cash value life insurance, but a positive association with the ownership of both term life insurance and cash value life insurance. Similarly, financial self-efficacy showed a negative association with non-ownership of any term life insurance, but a positive association with the ownership of both term life insurance and cash value life insurance. However, financial self-efficacy was negatively related to the ownership of only cash value life insurance. Third, financial satisfaction was associated with only the ownership of term life insurance negatively. Finally, life satisfaction showed a negatively significant association with non-ownership of both term life insurance and cash value life insurance.

Discussion and Implication

This study approached the demand for life insurance focusing on psychographics that includes both demographic factors and psychological factors. Specifically, those who had a higher level of external locus of control, those who had a higher level of financial self-efficacy, and those who had a higher subjective financial knowledge tended to have both forms of life insurance. All these finance-related psychological characteristics show that they would value the fundamental core of life insurance purchases more than other characteristics of life insurance (i.e., they would like to transfer the risk of loss of income) based on their perceptions and knowledge about the need for life insurance.

Regarding the traits of financial risk tolerance and financial satisfaction, those who take greater financial risk and are more financially satisfied recognize the need for life insurance, but these characteristics about financial attitude and evaluation could somewhat undervalue the need for term life insurance. This result was the opposite of life satisfaction. Those who were satisfied with their lives but not necessarily satisfied with their financial aspects would prefer ownership of term life insurance. Although financial satisfaction has been known to be an element of life satisfaction (Robb and Woodyard 2011), its effects on financial decisions, such as owning term life insurance, were not necessarily in the same direction.

Our findings show the different characteristics and primary purposes of term and cash value life insurance. Cash value life insurance was likely to be used to complement wealth accumulation vehicles rather than as a substitute for lost income from premature death, whereas term life insurance was desired as pure protection for the potential loss of future income. The results are consistent with previous work (Heo, Grable, and Chatterjee 2013), which suggests that the purpose and characteristics of cash value life insurance should not be treated in the same way as those of term life insurance.

Although previous researchers have identified the various factors that contribute to the likelihood of life insurance ownership, not much discussion about the subgroup analyses with psychographics was found. Our findings confirmed the importance of conducting separate analyses by policy ownership patterns (i.e., no ownership, only term life insurance, only cash value life insurance, and both term and cash value life insurance), and deepened the discussion about the factors related to life insurance ownership.

The study suggests the importance of a comprehensive approach to the study of life insurance ownership and the incorporation of psychological factors in the analysis. Various idiosyncratic characteristics of consumers, including financial, psychological, and demographic factors, should be considered along with the functional purposes of the life insurance being purchased in research and practices. When working with clients, financial practitioners can recognize to accommodate clients’ needs for different types of life insurance with the study. Consumers can be better served through an extended area of factors related to life insurance demand.

References

Asebedo, S. D., and M. C. Seay. 2018. “Financial Self-efficacy and the Saving Behavior of Older Pre-retirees.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 29 (2): 357–368.

Cobb-Clark, D. A., S. C. Kassenboehmer, and M. G. Sinning. 2016. “Locus of Control and Savings.” Journal of Banking & Finance 73: 113–130.

Diener, E., R. A. Emmons, R. J. Larsen, and S. Griffin. 1985. “The Satisfaction with Life Scale.” Journal of Personality Assessment 49 (1): 71–75.

Farrell, L., T. R. Fry, and L. Risse. 2016. “The Significance of Financial Self-efficacy in Explaining Women’s Personal Finance Behaviour.” Journal of Economic Psychology 54: 85–99.

Gitman, L. J., M. D. Joehnk, and R. S. Billingsley. 2014. Personal Financial Planning. 13th ed. Mason, OH: Cengage.

Grable, J. E. 2016. The Case Approach to Financial Planning Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Practice. 3rd ed. Erlanger, KY: The National Underwriter Company.

Grable, J. E., and J. W. Goetz. 2017. Communication Essential for Financial Planners: Strategies and Techniques. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Heo, W., J. E. Grable, and S. Chatterjee. 2013. “Life Insurance Consumption as a Function of Wealth Change.” Financial Services Review 22 (4): 389−404.

Heo, W., J. M. Lee, and N. Park. 2020. “Financial-Related Psychological Factors Affect Life Satisfaction of Farmers.” Journal of Rural Studies 80: 185–194.

Montalto, C. P., E. L. Phillips, A. McDaniel, and A. R. Baker. 2019. “College Student Financial Wellness: Student Loans and Beyond.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 40 (1): 3–21.

Nowicki, S., G. Ellis, Y. Iles-Caven, S. Gregory, and J. Golding. 2018. “Events Associated with Stability and Change in Adult Locus of Control Orientation over a Six-Year Period.” Personality and Individual Differences 126: 85–92.

Park, N., J. M. Lee, and W. Heo. 2020. “Life Satisfaction in Time Orientation.” Applied Research in Quality of Life 16: 1717–1731.

Rejda, G. E., and M. J. McNamara. 2016. Principles of Risk Management and Insurance. 13th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Peason.

Robb, C. A., and A. Woodyard. 2011. “Financial Knowledge and Best Practice Behavior.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 22 (1): 60–70.

Rotter, J. B. 1966. “Generalized Expectancies for Internal Versus External Control of Reinforcement.” Psychological Monographs: General and Applied 80 (1): 1–28.

Thoyts, R. 2010. Insurance Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Xiao, J. J., and B. O’Neill. 2018. “Propensity to Plan, Financial Capability, and Financial Satisfaction.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 42 (5): 501–512.