Journal of Financial Planning: March 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- Using primary data collected from an online survey in 2023, this study explored the investment beliefs, preferences, and behaviors of wealthy individuals. Among 1,000 respondents, 38 percent had investable assets of at least $1 million and were assigned to a high-net-worth cohort while the remaining 62 percent of respondents had investable assets between $250,000 and $999,999 and were assigned to an affluent cohort. A multivariate analysis was conducted, yielding some surprising results.

- Regarding portfolio construction, wealthier individuals were more likely to own separately managed accounts (SMAs) and alternative investments. No significant differences were found, however, regarding the ownership of cryptocurrency or incorporation of ESG factors into investment decision-making.

- Wealthier individuals indicated higher levels of subjective knowledge but were no less likely to have made investment mistakes due to emotions, suggesting the high-net-worth cohort displayed overconfidence in their abilities.

- Interest in building financial education was higher for wealthier individuals. In fact, approximately 84 percent of the high-net-worth cohort was very or somewhat interested in improving their financial skills.

- Surprisingly, no difference was found between the two cohorts in annual portfolio rebalancing practices. Encouraging wealthier investors to actively rebalance their portfolio is a key takeaway for practitioners.

- Among respondents who use a financial adviser, wealthier individuals were more likely to report their adviser “keeps my emotions in check.” This finding reinforces the qualitative benefits of relying on professional advice.

Matthew Sommer, Ph.D., CFA, CFP®, serves as Janus Henderson Investor’s lead behavioral finance researcher, where he and his team provide clients with insights regarding several topics related to practitioner best practices, regulatory and legislative trends, and wealth planning strategies.

Dr. Sonya Lutter is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNERTM professional and licensed marriage and family therapist. She serves as the inaugural director of financial health and wellness with the Texas Tech University’s School of Financial Planning, where she leads curriculum and continuing education opportunities in the areas of financial psychology, financial therapy, and financial behavior.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

People think differently about their situation based on socioeconomic and social class; and theoretically, people constantly make social categorizations wherein there is an in-group and an out-group (Hogg 2016). Once assigned or viewed as part of the group, there is often a very clear divide between group alliances regardless of personal attachment to members of the broader group (Hogg 2016). Meaning, someone who views themselves as “non-wealthy” will align with other “non-wealthy” people and see themselves in conflict or competition with the “wealthy” group. This conflict is likely based on perceived differences, yet little is known about actual differences in the investment beliefs, preferences, and behaviors of individuals based on wealth.

As of 2022, there were 7.4 million high-net-worth individuals representing $25.6 trillion in investable assets in North America (Capgemini 2023). For financial advisers, these wealthy individuals represent highly desirable clients; however, servicing these relationships requires a specific skill set and expertise. Financial advisers who excel in this market segment are adept at creating a differentiated experience based on each client’s unique needs and expectations. Not only must financial advisers possess technical expertise, but they also must be able to communicate clearly and effectively and build trust with family members and outside advisers. The delivery of exceptional client service has become even more critical in recent years given market and geopolitical uncertainty.

The purpose of the current study was to better understand the group categorization of the “high-net-worth” versus the “affluent.” Perceptions of the groups guide how financial advisers work with their clients. As described within the CFP Board’s principal knowledge topic of psychology of financial planning, the financial planner’s beliefs, values, and biases influence the planner–client relationship (CFP Board 2024). To help financial advisers gain insights into the investment beliefs, preferences, and behaviors of high-net-worth individuals, data were collected via an online survey in 2023 by a large U.S. asset manager. The full sample consisted of 1,000 U.S. respondents: 383 individuals represented high-net-worth households with at least $1 million in investable assets and 617 individuals represented households with between $250,000 and $999,999 in investable assets. Descriptive statistics and multivariate tests compared the responses of the high-net-worth and affluent cohorts across 25 different variables. Although many of the findings were anticipated, there were some surprising results and five critical action items financial advisers may wish to implement into their practice.

Literature Review

Demographic Characteristics

There is an apparent gender divide among the high-net-worth with many of the wealthy individuals in the U.S. being males. Klontz et al. (2015) compared a sample of investors with a net worth greater than $2.5 million to a sample of affluent investors with an average net worth of $582,000 and found that a larger percentage were male in the high-net-worth sample (71 percent versus 61 percent). Similarly, Kruger et al. (2017) found that 75 percent of respondents were male in a high-net-worth sample, with an average net worth of $958,923. In a comparable affluent sample with an average net worth of $288,660, 45 percent were male.

The gender divide is notable because men have tended to report higher levels of financial knowledge and confidence (FINRA Investor Education Foundation 2022). Perhaps not surprisingly, men were more likely to be the primary financial decision maker for wealthier households (Hanna et al. 2020). Using the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances’ (SCF) definition of “respondent,” which was assigned to the spouse most knowledgeable about household finances, the husband was the respondent in 90 percent of the survey’s wealthiest 1 percent of households. In comparison, the husband was the respondent in 56 percent of all households.

The literature suggests that most high-net-worth individuals are ages 55 and older. According to a Bank of America (2023) study of 1,052 U.S. investors with household assets of at least $3 million, 62 percent of wealthy individuals were baby boomers between the ages of 56 and 75. Another 9 percent of investors belonged to the silent generation (ages 76 and older). In a study of 1,622 clients of a large brokerage firm with at least $1 million in assets, 29 percent were between ages 55 and 64, 45 percent were between ages 65 and 74, and 13 percent were ages 75 and older (Bender et al. 2022).

The primary source of wealth for high-net-worth individuals appears to have been self-made versus received through generational transfer (Leckelt et al. 2019). It is possible that personality contributes to the profiles of those with self-made wealth—largely through entrepreneurship—such as low neuroticism, high openness and conscientiousness, and being more extroverted (Leckelt et al. 2022). Bank of America (2023) reported that only 28 percent of survey respondents had an affluent upbringing and received an inheritance. In contrast, 46 percent reported an affluent upbringing with no inheritance or a middle-class upbringing with a modest inheritance, and 27 percent reported a middle-class or poor upbringing with no inheritance.

Beliefs

High-net-worth individuals tend to have higher levels of financial satisfaction and lower levels of financial stress compared to affluent individuals (Klontz et al. 2015). Additionally, the wealthier cohort has significantly higher levels of internal locus of control, measured in part by questions regarding their confidence to solve problems and achieve goals. Perhaps not surprisingly, high-net-worth individuals tend to report significantly higher levels of self-assessed financial knowledge (Klontz et al. 2015).

Despite these beliefs, high-net-worth individuals harbor some financial concerns. In a study of affluent investors that oversampled high-income and high-net-worth households, increased stock market volatility and geopolitical uncertainty resulted in a year-over-year increase of 35 percentage points in the proportion of respondents worried about their financial future (Envestnet 2023). Similarly, a survey of millionaires found that the top threats to personal wealth were poor stock market performance, rising inflation, and U.S. government dysfunction (Dore 2023). Globally, high-net-worth individuals expressed concerns about the stock market and inflation but also cited rising interest rates as a top worry (Russell 2024).

Concerns about the economy, however, did not translate into a pessimistic outlook for the stock market among the wealthy. In a global survey of 8,500 individual investors with more than $100,000 in investable assets, the average expected portfolio return above inflation was 8.6 percent (Natixis 2023). These sentiments were consistent with intentions as 63 percent of global high-net-worth individuals planned to invest more in equities over the next 12 months, with one-third citing favorable valuations as the reason for the increase (Russell 2024).

In contrast, return expectations among affluent individuals appear more tempered. A Vanguard (2024) survey of 2,000 investors with more than $10,000 reported that the average expected return for stocks in 2024 was 5.7 percent. The American Association of Individual Investors (2024) conducts a weekly survey asking members if they believe the direction of the stock market over the next six months will be up (bullish), no change (neutral), or down (bearish). Heading into 2024, 46 percent of members were bullish, 28 percent were neutral, and 26 percent were bearish.

Preferences

As stated by Lusardi (2019), “even well-educated people are not necessarily savvy about money” (4). With increased financial literacy generally comes greater wealth (Lusardi and Mitchell 2014). Therefore, ascertaining preferences for financial education is an important step to building wealth.

Incorporating ESG factors into financial decision-making does not appear important to high-net-worth individuals. A much higher percentage of U.S. investors with assets less than $1 million are likely to hold socially responsible investments than wealthier cohorts (Junkus and Berry 2010; Mottola et al. 2022). There are generational differences among wealthy individuals, however, as 73 percent of respondents between ages 21 and 42 own sustainable investments in their portfolio, compared to 21 percent of respondents ages 43 and older, and 26 percent of wealthy respondents overall (Bank of America 2023).

Wealthy individuals also appear to lack interest in passive investments. According to Cerulli (2022), only 24 percent of high-net-worth individuals classified themselves as passive investors. This lack of adoption is in sharp contrast to the trend of the broader investment community moving toward low-cost index investing (Sabban 2024).

Most wealthy individuals are very (74 percent) or somewhat satisfied (23 percent) with their adviser (Bank of America 2023). The three most cited factors for satisfaction include reputation/trust (professionalism and honesty), relationship (overall quality and frequency of communications), and service (ease of doing business and accuracy) (Cerulli 2022). By comparison, quality of advice and investment performance were stated as the top four and five reasons, respectively.

Behaviors

Despite higher levels of self-assessed financial knowledge, high-net-worth individuals are prone to the same cognitive errors and emotional biases that plague many investors. For example, Klontz et al. (2015) found that high-net-worth individuals were more likely to display overconfidence by believing that they were a better-than-average investor and admitted to having made one or more investment mistakes.

After an investigation of the wealthy’s investment portfolios, Bender et al. (2022) uncovered two additional potential shortcomings. First, 83 percent of the stocks owned were U.S. companies, representing a significant home country bias. Second, 15 percent of respondents reported that a single stock represented at least 10 percent of their net worth. Among this subsample, 67 percent said that their concentrated position had no effect on the remaining portion of their equity allocation.

The literature finds that high-net-worth individuals are likely to use professional financial advice. Cerulli (2022) found that among households with at least $1 million in investable assets, 40 percent were adviser-reliant and 19 percent were advice seekers. Only 17 percent of respondents described themselves as “self-directed.” A Northwestern Mutual (2023) study found that 70 percent of wealthy Americans work with a financial adviser, nearly double the amount of the general population. A much higher percentage of adviser use (91 percent) was found among investors with at least $3 million in assets (Bank of America 2023).

Wealthy individuals are also more likely to have a financial plan. According to Northwestern Mutual (2023), 84 percent of wealthy individuals have a long-term plan that factors for the ups and downs of economic cycles. The percentage of the general population that has a long-term plan drops to 52 percent. The same research also found that 42 percent of high-net-worth individuals described themselves as a highly diligent planner (“I have a plan and do not deviate from it”) and 35 percent as a diligent planner (“I have a plan but sometimes deviate from it”). Among the general population, those who described themselves as a highly diligent planner or diligent planner were 20 percent and 30 percent, respectively.

Another key difference regarding the investment behaviors of high-net-worth and affluent individuals is their investment holdings. Wealthier individuals were more likely to own individual stocks (Bender et al. 2022). On average, 93 percent of high-net-worth respondents owned individual stocks, a far greater percentage than the 52 percent participation rate in the 2016 SCF population. Not all investment holdings among high-net-worth individuals, however, are uniform as there were notable differences based on age (Bank of America 2023). Three-quarters of the younger cohort felt it was no longer possible to achieve above-average returns using traditional stocks and bonds alone. Perhaps not surprisingly, therefore, while the average portfolio allocation among high-net-worth individuals to cryptocurrency was 3 percent, the allocation was 15 percent for respondents between ages 21 and 42. Additionally, the average allocation to alternative investments was 16 percent among the younger cohort, compared to 5 percent for respondents ages 43 and older.

Lastly, the non-financial benefits of working with a financial adviser cannot be understated. Envestnet (2023) found that what individuals appreciated most during recent fluctuations in the market was helping to remain focused on the long term regardless of a tough investment environment, peace of mind, and less overall stress and anxiety. According to Cerulli (2022), the three most cited factors that respondents rated as excellent or very good in describing their adviser relationship were takes time to understand my needs, goals, and risk tolerance (76 percent), provides transparency in interactions (76 percent), and explains financial analysis in a clear, straightforward way (75 percent).

Methods

Data & Sample

Partnering with a large U.S. asset manager, an online survey instrument was administered through the panel and data collection company, Dynata, from July to August 2023. The national online panel had more than 17 million panelists in over 90 countries. The survey was sent to U.S. residents between ages 25 and 95. Only those respondents with investable assets of $250,000 and who were the primary or shared financial decision maker for the household were allowed to complete the survey. Survey responses were collected until the number of responses reached 1,000 with at least 200 respondents with more than $1 million in investable assets. The survey instrument did not allow respondents to skip any questions.

Variable of Interest

Since there is no formal definition of wealth, Capgemini’s (2023) approach to market segmentation was used. Specifically, respondents with investable assets of $1 million and greater were categorized as high-net-worth and respondents with investable assets between $250,000 and $999,999 were categorized as affluent. Using these definitions, 38 percent of survey respondents were assigned to the high-net-worth cohort and 62 percent of survey respondents were assigned to the affluent cohort.

Demographic Variables

Several demographic characteristics were captured by the survey instrument including gender, household financial decision-making (primary or shared), employment status (employed or retired/not employed), marital status (married/partnered or single), income (less than $100,000, between $100,000 and $199,999, and $200,000 and greater), race (White or non-White), age, and risk tolerance (conservative, moderate, and aggressive).

Belief Variables

Several items were included in the survey to understand respondents’ investment beliefs including satisfaction with current financial condition, financial empowerment, and confidence in one’s ability to achieve financial goals. Financial knowledge was self-assessed with the question, “Overall, how would you describe your financial level for investing?” Regarding the current economic environment, respondents were asked, “As it relates to your financial situation, how concerned are you about the following over the next 12 months?” The areas explored were poor stock market performance, persistent inflation, risk of recession, and rising interest rates. Lastly, respondents were asked whether they believed the stock market would be higher, lower, or the same in one year.

Preference Variables

To gauge respondents’ investment preferences, they were asked, “How interested are you in financial education and building your knowledge of investments?” and “How important is it to you that your investments incorporate environmental or social responsibility factors?” Among mutual fund or ETF owners, respondents were asked to describe their mindset about active versus passive investment styles.

Among respondents who do not use a financial adviser on an ongoing basis, they were asked, “How likely are you to begin using a financial adviser in the next two years?” Respondents who indicated that they were not too likely or not all likely to hire an adviser were asked to choose from a list of reasons for opting not to receive assistance. Similarly, respondents who indicated that they were very or somewhat likely to use an adviser were asked to select from a list of services they wished to receive. Lastly, respondents who use a financial adviser on an ongoing basis were also asked, “Overall, how satisfied are you with your financial adviser?”

Behavior Variables

Among the investment behavior items, respondents were asked, “Do you agree or disagree with the statement, ‘Emotions have caused me to make mistakes with my investments (e.g., sell too soon, purchase exciting but risky investments),’” and “on which of these activities do you spend the most time? Rank order, giving a ‘1’ to the area you spend the most time on and a ‘5’ to the area you spend the least time on.” The activities were “following the financial markets,” “managing and/or reviewing my investments,” “following my favorite sports teams,” “watching shows on streaming services (e.g., Netflix, Hulu, Disney+),” and “following the news on social media.”

Also asked was, “When did you most recently proactively rebalance your investment portfolio (i.e., change the percentage of money you allocate to different asset classes like stocks, bonds, and cash)?” “Do you currently use a financial adviser on an ongoing basis to help you manage your savings and investments?” and “Do you have a financial plan for your future (a financial plan documents your financial situation, lists your goals, and sets a strategy to achieve your goals)?” Regarding portfolio construction, respondents were asked about investment products owned outside of workplace retirement plans. Lastly, among respondents who currently use a financial adviser, they were asked what services were being provided.

Empirical Strategy

To investigate the relationship between wealth levels and investment beliefs, preferences, and behaviors, 25 regression models were specified. Ordinal regression models were used when the dependent variable consisted of three or more categories and logistic regression models were used when the dependent variable consisted of two categories. In all 25 models, the variable of interest was the respondents’ wealth level (high-net-worth or affluent) and the control variables were gender, financial decision-maker, employment status, marital status, income, ethnicity, age, and risk tolerance.

Results

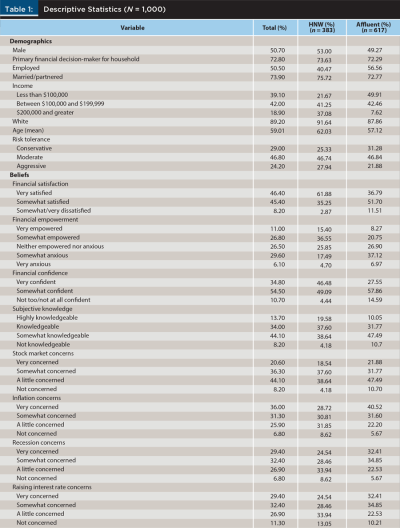

Information about the respondents’ demographic characteristics can be found in Table 1. Among the full sample, respondents were evenly divided by gender and slightly more than two-thirds (73 percent) were the primary financial decision maker for their household. Half of respondents were employed (50 percent) and the majority were married or partnered (74 percent). A plurality of respondents (42 percent) reported income between $100,000 and $199,000, and another 19 percent reported income of at least $200,000. Most respondents were White (89 percent) and the average age was 59. Almost half of respondents (46 percent) indicated their risk tolerance was moderate.

Applying the definitions of high-net-worth (investable assets of at least $1 million) and affluent (investable assets between $250,000 and $999,999), the full sample was divided into two wealth cohorts of 38 percent and 62 percent, respectively. When comparing the cohorts, a larger percentage of high-net-worth respondents were retired/not employed (60 percent versus 43 percent) and reported income of at least $200,000 (37 percent versus 8 percent). The mean age of high-net-worth respondents was 62, compared to 57 for affluent respondents. Additional descriptive statistics regarding respondents’ investment beliefs, preferences, and behaviors are provided in Table 1.

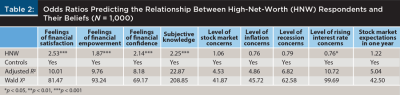

An abbreviated multivariate analysis of respondents’ beliefs can be found in Table 2 (full models are available upon request). High-net-worth respondents were associated with higher levels of satisfaction with their financial situation, feelings of empowerment when thinking about their personal finances, and confidence in meeting their financial goals. High-net-worth respondents were also more likely to indicate higher levels of subjective knowledge.

Although no differences were found between the two cohorts in the levels of concern regarding poor stock market performance, persistent inflation, and risk of recession, affluent respondents were more likely to be worried about rising interest rates. Both high-net-worth and affluent respondents shared similar expectations for the stock market over the next 12 months.

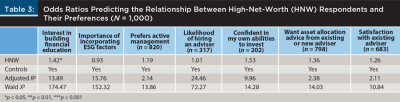

An abbreviated multivariate analysis of respondents’ preferences can be found in Table 3 (full models are available upon request). The high-net-worth cohort indicated higher levels of interest in building their financial knowledge although no significant differences were found regarding the importance of ESG factors, active versus passive investment management, and likelihood of hiring an adviser. While the most cited reason by respondents for being not too likely or not at all likely to hire an adviser was “confidence in my own abilities to invest,” there were no differences between the two cohorts. Similarly, the most desired service of asset allocation advice among those very or somewhat likely to hire an adviser was consistent regardless of wealth levels. Lastly, the results showed relatively similar levels of satisfaction with existing financial advisers.

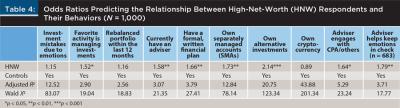

An abbreviated multivariate analysis of respondents’ behaviors can be found in Table 4 (full models are available upon request). Both cohorts were equally susceptible to making an investment mistake due to their emotions. When asked how respondents spend their time, high-net-worth respondents were more likely to manage or review their investments, although no differences were found regarding following the financial markets, watching streaming services, following the news on social media, or following favorite sports teams.

While both cohorts shared similar annual rebalancing practices, the high-net-worth cohort was more likely to currently have an adviser and have a formal, written financial plan. The wealthier cohort was also more likely to own separately managed accounts (SMAs) and alternative investments, but cryptocurrency ownership was similar to the affluent cohort. Among services presently provided by financial advisers, the high-net-worth cohort was more likely to report that their adviser engaged with CPAs and other outside advisers and helped to keep emotions in check. There were no differences found among the other services listed including provides financial education, engages with spouses and other family members, offers access to unique investments, and provides peace of mind.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the investing habits of high-net-worth individuals by comparing their beliefs, preferences, and behaviors to affluent individuals. While many of the findings were anticipated, the results did uncover potential blind spots of high-net-worth individuals not previously considered. These unexpected results add to the existing body of literature and provide a starting point for future research. Also, financial advisers can use these findings to more effectively engage and service wealthy clients.

The results concur with earlier research that linked high-net-worth individuals with higher levels of financial satisfaction and financial empowerment, while also having higher levels of confidence in the ability to reach financial goals (Klontz et al. 2015). Additionally, the high-net-worth cohort indicated higher levels of self-assessed financial knowledge, aligning with existing literature (Klontz et al. 2015). This result may be partially explained by the high-net-worth cohort’s skew toward a male and older demographic. Both these characteristics have been found to be associated with higher perceptions of one’s financial knowledge (FINRA Investor Education Foundation 2022).

One of the unique aspects of this study was to examine the levels of concern across the present economic backdrop of volatile stock markets, persistent inflation, risk of a recession, and rising interest rates. Similar to earlier studies (Dore 2023; Envestnet 2023; Russell 2024), a meaningful percentage of both wealthy and affluent individuals reported some levels of concern about the economy. The only significant difference between the two cohorts, however, was that wealthier individuals harbored fewer concerns regarding rising interest rates. Perhaps the ability to service higher debt payments compared to affluent individuals accounted for this difference. Both the high-net-worth and affluent cohort displayed cautious optimism regarding the stock market’s performance over the next 12 months. These views were similar to the findings of Vanguard (2024) and the American Association of Individual Investors (2024).

Compared to affluent individuals, high-net-worth investors expressed higher levels of interest in building their financial knowledge. In fact, 84 percent of high-net-worth respondents indicated they were very or somewhat interested in improving their financial skills. Prior research has linked financial self-efficacy with help-seeking behaviors, such as participating in a financial literacy program (Lim et al. 2014). Both cohorts indicated similar views regarding the importance of incorporating ESG factors into investment decisions. This finding was surprising given existing research that suggests younger, female, and less wealthy investors have the highest levels of interest in ESG investing (Junkus and Berry 2010; Mottola et al. 2022). While high-net-worth and affluent individuals held similar preferences regarding active versus passive investing, it is notable that 29 percent of wealthy investors preferred a mainly active approach compared to 16 percent who preferred a mainly passive approach. The balance of respondents preferred a mix or had no preference, closely aligning with earlier research (Cerulli 2022).

It was also surprising to learn that high-net-worth individuals were no more likely to consider hiring an adviser over the next two years than were affluent individuals, given the wealthy’s demand for professional advice (Northwestern Mutual 2023). The primary reason behind the lack of interest was the confidence high-net-worth individuals had in their own financial abilities, while among likely advice seekers, asset allocation was the most desired service. Lastly, both cohorts were pleased with the services provided by their current financial adviser. In fact, these 99 percent of high-net-worth individuals are very or somewhat satisfied with their relationship, suggesting unadvised investors may be unaware of all the benefits that can be obtained from working with a professional.

Regarding investor behaviors, high-net-worth individuals were no more likely to have made an investment mistake due to their emotions, despite higher levels of subjective knowledge. As suggested by Bender et al. (2022) and Klontz et al. (2015), high-net-worth individuals are susceptible to emotional biases and cognitive errors. Despite these missteps, however, high-net-worth individuals were more likely to spend their time managing their investments. One area that may warrant additional research is the number of hours different wealth cohorts spend attending to their finances. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023), the average American spends 1.2 minutes a day on household financial management, compared to 12 minutes a day using a computer for leisure activities. Learning how much time high-net-worth and affluent individuals devote to financial and investment management versus leisure activities may greatly benefit the profession.

It was unexpected that wealthier individuals were no less likely to rebalance their portfolio compared to affluent individuals. A deeper understanding of why only 45 percent of high-net-worth individuals proactively rebalanced their portfolios annually is another area that may warrant additional investigation. The lack of annual rebalancing practices is especially puzzling given that high-net-worth individuals were more likely to have a formal written financial plan and rely on a financial adviser.

It stands to reason wealthier individuals were more likely to own separately managed accounts and alternative investments, given the tax and diversification benefits, respectively. A lower percentage of high-net-worth individuals owned cryptocurrency, which was expected given that most of the demand is from younger investors who comprise a small percentage of high-net-worth market (Bank of America 2023), although the difference was not statistically significant.

Among the services provided by financial advisers, high-net-worth individuals were more likely to cite coordination with CPAs and outside advisers and keeping emotions in check. These findings support earlier work that highlighted the importance of the non-financial benefits provided by financial advisers (Cerulli 2022; Envestnet 2023). High-net-worth individuals are likely to have more complex finances than affluent individuals, requiring the assistance of attorneys, CPAs, and other professionals. Coordination among these professionals is paramount to achieving the best possible outcomes for mutual clients and it is not surprising to see advisers embrace a collaborative approach. Additionally, helping high-net-worth investors manage the emotions associated with complex planning needs such as divesting concentrated stock positions or planning for the succession of a family-owned business are unique aspects of serving the wealthy.

Implications

There are five key takeaways for financial advisers who presently work with, or aspire to work with, high-net-worth clients:

- Enhance awareness and possible use of separately managed accounts and alternative investments.

- Temper investment overconfidence.

- Build financial literacy.

- Proactively rebalance portfolios.

- Promote the non-financial benefits of professional advice.

Each of these recommendations is expanded upon in the paragraphs that follow.

First, the use of separately managed accounts and alternative investments are largely untapped opportunities as only 26 percent and 19 percent of high-net-worth respondents report owning these products. SMAs are generally considered a more tax-efficient investment compared to mutual funds. These products also have lower fees and are quickly becoming the vehicles of choice (in addition to ETFs) for higher income and wealthier investors (Hearts & Wallets 2023). When added to a traditional asset allocation of stocks and bonds, portfolios that also include the most important alternative investments, such as hedge funds, managed futures, real estate, private equities, and commodities, provide superior risk-adjusted returns, particularly during periods of market shocks (Fischer and Lind-Braucher 2010).

Second, financial advisers can help high-net-worth individuals temper investment overconfidence. Overconfident investors frequently and consistently overestimate their ability (Kahneman 2011), and the current results found that despite higher levels of self-assessed financial knowledge, high-net-worth individuals were no less likely to avoid investment mistakes than affluent individuals. In many cases, high-net-worth individuals have enjoyed enviable levels of career success in their chosen field. These individuals may mistakenly believe their professional traits are transferable attributes for successful investing. Characteristics of overconfident investors include beliefs that studying the past will help predict the future, attributing the good fortune of a bull market to their stock selection abilities, and an overreliance on intuition (Kahneman 2011).

Two counseling techniques that may be helpful with overconfident clients are subjective probability interval estimation (SPIES) (Lurtz 2020) and premortem planning (Klein 2007). SPIES is a graphical representation of all possible outcomes. Premortem planning starts by posing the question, “What is the worst outcome and why would that occur?” Next, ask, “What is the best outcome and why would that occur?” Presenting both good and bad outcomes reminds investors of suboptimal outcomes not previously considered.

Third, it is recommended that financial advisers help build their client’s financial literacy. In the current study, 84 percent of high-net-worth individuals were very or somewhat interested in building their financial education, yet only 54 percent were presently receiving financial education from their adviser. One area receiving increased levels of attention among financial advisers is longevity literacy. Household income has been found to be positively related to life expectancy, and at the extreme ends of the income distribution, the differences in life expectancies between the richest 1 percent and poorest 1 percent of individuals is 14.6 years for men and 10.1 years for women (Chetty et al. 2016). Also, higher levels of longevity literacy have been linked to positive behaviors such as planning and saving for retirement (Yakoboski et al. 2022), which are critical to ensuring clients maintain sufficient financial resources throughout their lifetimes.

Fourth, financial advisers are encouraged to educate wealthy clients about the benefits of proactive rebalancing. It was surprising that there were no discernible differences in rebalancing behaviors between high-net-worth and affluent respondents, since annual rebalancing of a 60/40 portfolio may add up to 14 basis points in incremental annual return (Kinniry et al. 2022). Even more important is the “buy low and sell high” discipline that results from sound rebalancing practices. If left unchecked, the portfolio will drift from the targeted asset allocation and may become misaligned with the investor’s original risk and return preferences.

Fifth, financial advisers should stress the qualitative benefits of professional advice when talking to prospective clients. Helping clients manage their emotions during the ups and downs of the market may add up to 100 to 200 basis points in annual net return (Kinniry et al. 2022). DALBAR (2024) has consistently found that investors underperform the markets by an average of 300 basis points annually, largely due to selling low and buying high. It is important to note that much of the emotion-based conversation can happen with the financial adviser leading the conversation in a therapeutic way without being a therapist with the proper training. High-net-worth individuals who indicated that the primary reason for not wanting to work with a financial adviser was the confidence in their ability to “do it themselves” may not be fully aware or appreciate the emotional support advisers provide clients. Also, engaging with outside professionals such as attorneys and CPAs to provide advice that is complementary to other aspects of a client’s financial picture not under the financial adviser’s direct purview is another benefit that may not be obvious to some wealthy individuals.

Conclusion

This study explored the investment beliefs, preferences, and behaviors of high-net-worth and affluent individuals. Limitations to the generalizability of the results exist. When working with populations that differ from the one used in this study, it is possible that the preferences, beliefs, and behaviors of individuals will vary. Additionally, some of the regression models generated a very low r-square. Readers can interpret these results to mean that respondents’ wealth levels and other demographic characteristics explained only a small fraction of the variability of the beliefs, preferences, and behaviors investigated in each model. There are other, unidentified factors at play, which offer the opportunity for additional study and analysis.

While many of the findings were expected, there are five immediate calls to action for financial advisers interested in serving wealthy clients. These items include a greater adoption of separately managed accounts and alternative investments; using the SPIES (Lurtz 2020) and premortem planning (Klein 2007) techniques to temper investment overconfidence; improving client financial literacy, particularly regarding accurately estimating one’s life expectancy; encouraging broader use of proactive portfolio rebalancing; and stressing the non-financial benefits of working with an adviser among high-net-worth prospects.

Citation

Sommer, Matthew, and Sonya Lutter. 2025. “An Exploratory Study of the Wealthy’s Investment Beliefs, Preferences, and Behaviors.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (3): 56–71.

References

American Association of Individual Investors. 2024. “The AAII Investor Sentiment Survey.” https://www.aaii.com/sentimentsurvey.

Bank of America. 2023. 2022 Bank of America Private Bank Study of Wealthy Americans. https://mlaem.fs.ml.com/content/dam/ust/articles/pdf/2022-BofaA-Private-Bank-Study-of-Wealthy-Americans.pdf.

Bender, S., J.J. Choi, D. Dyson, and A. Z. Robertson. 2022. “Millionaires Speak: What Drives their Personal Investment Decisions?” Journal of Financial Economics 146 (1): 305–330.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2023. “Time Spent in Detailed Primary Activities and Percent of the Civilian Population Engaged in each Activity.” www.bls.gov/tus/tables/a1-2023.pdf.

Capgemini. 2023. World Wealth Report. https://www.capgemini.com/insights/research-library/world-wealth-report/.

Cerulli. 2022. “U.S. High-Net-Worth and Ultra-High-Net-Worth Markets.” www.cerulli.com/reports/us-high-net-worth-and-ultra-high-net-worth-markets-2022.

CFP Board. 2024. “Psychology of Financial Planning.” https://www.cfp.net/knowledge/psychology-of-financial-planning.

Chetty, R., M. Stepner, S. Abraham, et al. 2016. “The Association between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States: 2001-2014.” JAMA 315 (16): 1750–1766.

DALBAR. 2024. “Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior.” www.dalbar.com/catalog/product/168.

Dore, K. 2023, June 7. “Millionaires See Market Volatility, Inflation among Biggest Threats to Wealth, CNBC Survey Finds.” CNBC. www.cnbc.com/2023/06/07/millionaires-biggest-wealth-threats-cnbc-survey.html.

Envestnet. 2023. “Unlock the Mindset of Today’s Affluent Investor.” https://newsroom.envestnet.com/2023-12-06-Unlocking-the-Needs-of-Todays-Affluent-Investors,-and-Opportunities-in-Each-Generation,-for-Advisors.

FINRA Investor Education Foundation. 2022. Investors in the United States: The Changing Landscape. www.finrafoundation.org/sites/finrafoundation/files/NFCS-Investor-Report-Changing-Landscape.pdf.

Fischer, E. O., and S. Lind-Braucher. 2010. “Optimal Portfolios with Traditional and Alternative Investments: An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Alternative Investments 13: 58–77.

Hanna, S. D., K. T. Kim, S. Lindamood, and S. T. Lee. 2021. “Husbands, Wives, and Financial Knowledge in Wealthy Households.” Financial Planning Review 4 (1): e1110.

Hearts & Wallets. 2023, October 26. “Separately Managed Accounts Grow, Mutual Funds Stagnate, and the Board-Level Competitive Imperative for Asset Managers.” www.heartsandwallets.com/docs/press/press_release_2023_10_26_SMAs_Grow_Mutual_Funds_Decline_Competitive_Imperative_Asset_Managers.pdf.

Hogg, M. A. 2016. “Social Identity Theory.” In Understanding Peace and Conflict Through Social Identity Theory. Peace Psychology Book Series, eds. S. McKeown, R Haji, and N. Ferguson. Springer International Publishing.

Junkus, J. C., and T. C. Berry. 2010. “The Demographic Profile of Socially Responsible Investors.” Managerial Finance 36 (6): 474–481.

Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Kinniry, F. M., C. M. Jaconetti, M. A. DiJoseph, D. J. Walker, and M. C. Quinn. 2022. “Putting a Value on your Value: Quantifying Vanguard’s Advisor’s Alpha.” Vanguard. https://advisors.vanguard.com/insights/article/putting-a-value-on-your-value-quantifying-advisors-alpha.

Klein, G. 2007, September. “Performing a Project Premortem.” Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2007/09/performing-a-project-premortem.

Klontz, B. T., P. Sullivan, M. C. Seay, and A. Canale. 2015. “The Wealthy: A Financial Psychological Profile.” Counseling Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 67 (2): 127–143.

Kruger, M., J. E. Grable, and S. S. Fallaw. 2017. “An Evaluation of the Risk-Taking Characteristics of Affluent Households.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (7): 38–47.

Leckelt, M., J. König, D. Richter, M. D. Back, and C. Schröder. 2022. “The Personality Traits of Self-Made and Inherited Millionaires.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9 (1): 1–12.

Leckelt, M., D. Richter, C. Schröder, A. C. P. Küfner, M. M. Grabka, and M. D. Back. 2019. “The Rich Are Different: Unravelling the Perceived and Self-Reported Personality Profiles of High-Net-Worth Individuals.” British Journal of Psychology 110 (4): 769–789.

Lim, H., S. J. Heckman, J. C. Letkiewicz, and C. P. Montalto. 2014. “Financial Stress, Self-Efficacy, and Financial Help-Seeking Behavior of College Students.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 25 (2): 148–160.

Lurtz, M. 2020, December 9. “How Overconfidence Can Aid Entrepreneurs and the Challenges of Advising Those Who Can’t See the Risk They Are Taking.” Nerd’s Eye View [blog]. www.kitces.com/blog/entrepreneurs-risk-taking-confidence-overestimation-overplacement-overprecision-subjective-probability-interval-estimates/.

Lusardi, A. 2019. “Financial Literacy and the Need for Financial Education: Evidence and Implications.” Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics 155 (1): 1–8.

Lusardi, A., and O. S. Mitchell. 2014. “The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence.” Journal of Economic Literature 52 (1): 5–44.

Mottola, G., O. Valdes, R. Ganem, and A. Fontes. 2022, March. “Investors Say They Can Change the World, if They Only Knew How: Six Things to Know About ESG and Retail Investors. FINRA Investor Education Foundation. www.finrafoundation.org/sites/finrafoundation/files/Consumer-Insights-Money-and-Investing.pdf.

Natixis. 2023, June 21. “Individual Investors Still Expect Double Digit Investment Returns Despite New Market Environment.” www.im.natixis.com/en-intl/about/newsroom/press-releases/2023/individual-investors-still-expect-double-digit-investment-returns-despite-new-market-environment.

Northwestern Mutual. 2023. 2023 Planning & Progress Study: High Net Worth. https://filecache.mediaroom.com/mr5mr_nwmutual/178995/Wave%20VI%20High%20Net%20Worth.pdf.

Russell, B. 2024, March 26. “Capital Group Survey Reveals High-Net-Worth Investors Have Large Cash Holdings and Could Miss Out on Market Opportunities.” IFA Magazine. https://ifamagazine.com/capital-group-survey-reveals-high-net-worth-investors-have-large-cash-holdings-and-could-miss-out-on-market-opportunities/.

Sabban, A. 2024, January 17. “It’s Official: Passive Funds Overtake Active Funds.” Morningstar. www.morningstar.com/funds/recovery-us-fund-flows-was-weak-2023.

Vanguard. 2024, January 23. “Investor Pulse: Optimism for 2024.” https://corporate.vanguard.com/content/corporatesite/us/en/corp/articles/investor-pulse-optimism-for-2024.html.

Yakoboski, P. J., A. Lusardi, and A. Hasler. 2022. “Financial Literacy, Longevity Literacy, and Retirement Readiness.” TIAA Institute & Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center. www.tiaa.org/content/dam/tiaa/institute/pdf/insights-report/2023-01/longevity_literacy_financial_literacy_and_retirement_readiness.pdf.