Journal of Financial Planning: October 2024

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Peter Lazaroff, CFA, CFP®, is the chief investment officer at Plancorp (www.plancorp.com), where he is responsible for overseeing the development, implementation, and communication of investment strategy. Peter is also the author of Making Money Simple and host of The Long-Term Investor podcast. Learn more at www.thelongterminvestor.com.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Diversifying a concentrated stock position is crucial for investors with significant wealth tied up in a single company’s stock. Such positions can arise from employee compensation plans, inheritance, or a successful investment. While these positions often represent a windfall, they also pose significant risks to an investor’s financial stability.

A concentrated stock position makes an investor’s portfolio highly vulnerable to adverse events affecting that company. This lack of diversification can lead to dramatic portfolio fluctuations and a higher risk of financial loss. Moreover, the substantial tax implications of selling a large, appreciated stock position often deter investors from taking necessary action.

Managing these positions requires a strategic approach that carefully considers the tax consequences of diversification strategies. In this article, we will explore the challenges associated with concentrated stock positions and discuss effective strategies for diversifying these holdings while minimizing tax burdens. By understanding these strategies, investors can make informed decisions aligned with their long-term financial goals and tax considerations.

Why Investors Own Concentrated Stock Positions

There are three common ways in which individuals acquire concentrated stock positions. The first is through employee compensation plans. Companies offer stock options, restricted stock units, or other equity-based compensation as part of their benefits packages to align the interests of employees with those of shareholders. As these options vest over time and the company grows and succeeds, employees may find that a substantial portion of their wealth is tied up in their company’s stock.

Inheritance is another prevalent source of concentrated stock positions. In some instances, heirs receive significant stock holdings as part of an estate—particularly if the decedent avoided selling highly appreciated positions to benefit from the cost basis step-up at death—but resist selling those positions for emotional or sentimental reasons. In other cases, heirs inherit highly appreciated stock positions in a trust or other legal structure that does not receive a step-up in basis, so they continue to hold the position to avoid capital gains taxes.

Concentrated stock positions can also result from holding onto a single, exceptionally well-performing stock, leading to a substantial portion of an individual’s wealth being tied to that investment. Investors who have witnessed substantial gains are often reluctant to sell due to the tax consequences and fear of missing out on future gains. They also tend to build an emotional attachment to a company’s growth story that they have closely followed and supported. This along with the allure of past performance can cloud judgment, making it difficult to make objective decisions about diversification.

Risks Posed by Concentrated Stock Positions and Challenges to Diversification

Whether a concentrated stock position is the result of good fortune, loyalty, or legacy, it presents its holder with unique challenges.

From an investment perspective, the most significant challenge is the lack of diversification. A portfolio dominated by one stock is highly vulnerable to that company’s fortunes. A downturn in performance can lead to substantial financial losses, amplified by market volatility and broader economic conditions. Numerous studies provide compelling evidence that the majority of individual stocks fail to outperform the broader market, and even risk-free assets, over their lifetimes.

One notable example is “Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?” (Bessembinder 2018), which analyzes the total returns of U.S. common stocks from 1926 to 2016. Bessembinder’s research finds that the median stock generated a return of –3.66 percent per year, and only 42.6 percent of individual stocks had lifetime returns that exceeded those of one-month Treasury bills. Meanwhile, the top 4 percent of stocks (1,092 out of 25,967) accounted for all the net wealth creation during that period, with only 90 companies (0.33 percent) accounting for more than half of the return.

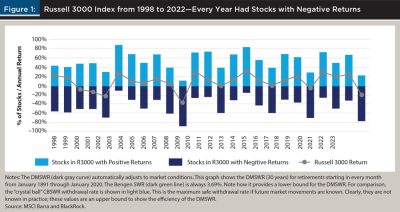

A more recent example comes from J.P. Morgan’s “Agony and Ecstasy” (Cembalest 2021), which finds that 66 percent of all stocks trail the Russell 3000 from 1980–2020. Goldman Sachs research from 1986–2022 shows the median stock in the Russell 3000 had a 31 percent chance of losing more than 30 percent of its value in one year versus a 5 percent chance for the Russell 3000 index. Even more, 36 percent of Russell 3000 stocks suffered a permanent impairment—defined as a stock that loses more than 75 percent of its value and does not recover to 50 percent of its original value.

These findings underscore the critical importance of diversification for long-term success and highlight the risks of relying on individual stocks. The significant skewness in returns means the likelihood of any given individual stock beating the market is low. Meanwhile, diversification through broad-based market indices captures gains from high-performing stocks and provides more stable, predictable returns.

Unfortunately, achieving that diversification comes with its own set of challenges. Having a large portion of wealth tied up in a single stock can create a strong emotional connection to that company, which can impede rational decision-making and make it difficult to manage the position objectively. The high stakes can also cause anxiety, preventing timely and rational decisions due to fear of making the wrong move. This stress is often exacerbated by market volatility, news events, or personal financial needs, resulting in inaction and further risk exposure.

Even if the behavioral aspects of diversifying are conquered, one still must navigate meaningful tax implications. Selling a large, appreciated stock position can result in substantial capital gains taxes, often deterring investors from diversifying. However, strategically managing these tax consequences is crucial for long-term financial health.

While the immediate cost of selling may seem prohibitive due to high capital gains taxes, the cost of inaction can be even greater. Holding onto concentrated positions increases exposure to market volatility and company-specific risks, potentially leading to financial losses that far outweigh the tax liability. Therefore, it is essential to explore strategies that can help investors diversify their holdings while effectively managing these tax challenges.

Strategies for Unraveling Concentrated Stock Positions

Strategically managing concentrated stock positions starts with identifying objectives and constraints. The best approach will differ for investors based on position size, cost basis, current and future tax brackets, liquidity needs, time horizon, and risk tolerance.

Separately Managed Accounts (SMAs) with Tax Loss Harvesting Emphasis

The most-common strategy for diversifying in a tax-neutral manner is using tax loss harvesting to offset capital gains realized from liquidating a single stock position. Tax loss harvesting is an investment strategy where underperforming investments are sold to realize losses, which can offset taxable capital gains from other investments. Later, the sold investments can be replaced with similar ones to maintain the desired portfolio allocation without violating the wash-sale rule.

While many investors already engage in tax loss harvesting their mutual funds and ETFs, those opportunities are limited to poor market environments. Separately managed accounts (SMAs), on the other hand, tax loss harvest at the individual security level, which allows for more opportunities across all market environments. This facilitates a smoother transition to a diversified portfolio.

By funding an SMA with the concentrated stock position plus cash, the SMA manager can build a diversified portfolio around the concentrated position while strategically realizing losses to reduce the tax burden associated with incremental liquidations of the concentrated stock.

While this strategy offers significant benefits, there are a few potential downsides to consider. One issue is portfolio ossification, where the diminishing opportunities to harvest new losses leave the account holding primarily positions with gains. This can result in a less dynamic and potentially underperforming portfolio. Another consideration is the need for cash up front to fully capitalize on tax loss harvesting opportunities, which can be challenging for investors who already have a significant portion of their wealth tied up in existing positions.

Contribute Concentrated Stock to an Exchange Fund

Investors with low cost basis positions, high tax rates, and minimal liquidity constraints may consider using an exchange fund to achieve instant diversification without triggering immediate tax consequences.

By contributing their concentrated stock holdings to the fund, investors receive a pro rata share of a diversified portfolio comprising stocks contributed by other investors. Typically structured as a limited partnership, an exchange fund allows qualified investors (those with $5 million of investable assets) to exchange their concentrated stock positions for units of the fund.

To meet tax deferral requirements, investors usually need to remain invested in the fund for at least seven years. After this period, they can redeem their units and receive a diversified basket of 25–30 stocks, maintaining the original cost basis of their contribution. Upon exiting the fund, the next step often involves placing these securities in a lower-cost SMA for ongoing management to a broad market index benchmark.

The benefits of an exchange fund approach are generally larger for investors with lower cost basis and higher capital gains tax rates. However, the benefits need to be weighed against potential costs and liquidity constraints. Exchange funds tend to charge higher fees than market ETFs due to additional costs related to tax requirements, which can reduce the overall benefit of this approach.

One trade-off is the lock-up period, during which investors cannot access their capital without penalties. This lack of liquidity can be a drawback for those needing access to their funds in the near term. Nevertheless, the benefit of deferring capital gains taxes and achieving immediate diversification often outweighs the temporary illiquidity for many investors.

For those not constrained by liquidity, an exchange fund can be a tax-efficient way to transition from a concentrated stock position to a diversified portfolio. The main advantages include immediate diversification, the deferral of capital gains, and the potential for pre-tax return compounding.

Use of Options to Meet Specific Financial Goals

While exchange funds can be an excellent solution for some investors, they come with drawbacks such as a long lock-up period, loss of current dividend income, and the complexity of K-1 tax reporting. Additionally, capacity constraints may limit access to these funds based on an individual’s holdings.

An alternative to exchange funds is to achieve market returns and tax loss harvesting benefits using options strategies within an SMA. This approach swaps single stock risk for market risk while maintaining daily liquidity and preserving dividend income. The strategy unfolds in two steps. First, a collar option overlay is created by purchasing put options on the stock and selling call options simultaneously. This hedges downside risk with the put options, while the proceeds from the sold call options cover the cost of the puts, effectively creating a costless collar.

Once the stock position is collared, the strategy shifts to a risk reversal or “squash” approach. This involves selling put options on an equity or bond index and using the premiums to buy call options on the index. This transition shifts the concentrated equity exposure to broader market exposure without additional cost, providing a cashless position.

A notable advantage of this approach compared to an exchange fund is the opportunity to directly address tax liabilities. Exchange funds offer immediate diversification, but merely delay capital gains recognition and leave investors with a tax burden should they want to achieve liquidity. However, strategic use of options strategies allows for a concentrated stock to be liquidated over time.

When the options make money, investors can use the premiums to pay taxes from a partial liquidation of the concentrated stock position. Alternatively, when the options lose money, those losses can be used to offset recognized gains from a partial liquidation of the concentrated stock position. By strategically liquidating the concentrated stock over time, investors can reduce overall tax exposure, improve the stock’s basis, and ultimately lower the embedded capital gains liability.

Diversify Gradually

Gradual diversification is a straightforward yet effective strategy for managing concentrated stock positions. This approach involves systematically selling portions of the concentrated stock and reinvesting the proceeds into a diversified portfolio over time. By spreading out the sales, investors can manage the tax impact more effectively and reduce the risk of timing the market poorly.

For instance, an investor might decide to sell a specific percentage of their concentrated stock position each quarter and use the proceeds to buy a mix of diversified assets, such as mutual funds, ETFs, or other individual stocks. This method reduces the psychological and financial impact of selling a large position all at once and allows for a more measured approach to diversification.

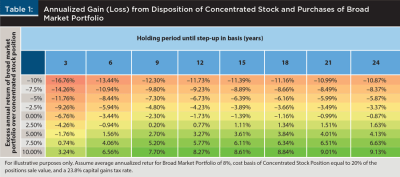

More often than not, it doesn’t make sense to let the tax tail wag the dog. If you truly believe in the historical research showing that individual stocks dramatically underperform the overall market, then the outcome of selling a stock, paying the capital gains, and reinvesting in the broad market will be determined by (1) how the stock performs relative to the broad market after the sale, and (2) how long the owner would have held the stock otherwise (until a step-up in cost basis at death).

Using Table 1 as a guide, this strategy seems best suited for investors with at least a 10-year horizon and would make less sense for someone closer to 80 as they will be able to get a step-up in basis at death.

In only a small number of cases would the impact of taxation negate the benefits of selling, so most concentrated stock owners should probably reduce the weight they put in their tax bill when discussing a strategic plan to reduce exposure to a concentrated position.

Additional Strategies for Mitigating Concentrated Stock Risks in a Tax-Friendly Manner

Beyond the primary strategies discussed, there are several other approaches investors can consider when managing their concentrated stock positions. These include:

By transferring concentrated stock into a CRT, investors can receive a charitable deduction, avoid immediate capital gains taxes, and receive an income stream from the trust. The CRT sells the stock, reinvests the proceeds in a diversified portfolio, and pays the investor a percentage of the trust’s value annually. Upon the investor’s death or after a specified period, the remaining assets go to the designated charity. This strategy not only aids in diversification but also supports philanthropic goals, providing both financial and social benefits.

Donating appreciated stock to a DAF allows investors to receive an immediate tax deduction, avoid capital gains taxes, and recommend grants to their favorite charities over time. The DAF sells the stock and reinvests the proceeds in a diversified portfolio, while the investor can advise on how and when the funds are distributed to charities. This approach offers flexibility in charitable giving and helps manage concentrated positions without triggering significant tax events.

Investors can gift shares of their concentrated stock to family members. This can be particularly tax-efficient if the recipients are in a lower tax bracket. The annual gift tax exclusion allows individuals to gift up to a certain amount per year, per recipient, without incurring gift taxes. This strategy can reduce the size of the concentrated position and shift future appreciation to family members, potentially lowering the overall family tax burden. Additionally, gifting stock can help with estate planning by reducing the size of the taxable estate.

By considering these additional strategies, investors can further tailor their approach to managing concentrated stock positions to their specific financial goals and circumstances.

Conclusion

Concentrated stock positions, while often the result of good fortune, present unique challenges that require careful management. By understanding the risks and employing strategic diversification techniques, investors can reduce their exposure and improve their portfolio’s overall stability. Whether through SMAs, exchange funds, option collars, or gradual diversification, the key is to take a proactive approach to managing concentrated positions, ensuring long-term financial health and security.

References

Bessembinder, H. 2018. “Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?” Journal of Financial Economics 129 (3): 440–457.

Cembalest, Michael. 2021, March 15. “The Agony & The Ecstasy.” J.P. Morgan. https://privatebank.jpmorgan.com/nam/en/insights/latest-and-featured/eotm/the-agony-the-ecstasy.