Journal of Financial Planning: September 2023

Executive Summary

- With the growth of social media use among consumers, financial practitioners may find it worthwhile to understand investors’ use, knowledge, and attitudes regarding social media and investment decision-making.

- This study used data from the 2021 National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) to investigate the characteristics of consumers using social media as an information source for investment advice.

- The results indicate investors using social media as an information source for investment decisions are younger, less likely to be women, less likely to have higher-valued investment portfolios, and have lower objective financial knowledge.

- About 26 percent of social media users traded more than 10 times a month compared to about 17 percent of non-social media users. Holding ETFs and microcap or penny stocks in one’s investment portfolio was associated with using social media for investing.

- When compared to non-social media users, those using social media to make investment decisions were significantly more likely to report being motivated to invest (1) to have a social activity/connect with others or due to peer influence, (2) to be socially responsible, and (3) to learn about investing.

- Future research should explore whether consumers use social media for investment decisions as a substitute or complement to working with financial professionals.

Miranda Reiter, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor in the School of Financial Planning at Texas Tech University. Her research focuses on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the financial planning profession and consumer financial behavior. She is the author of the Audible audiobook, Six Steps to Manage Your Money.

Di Qing, Ph.D., is a lecturer in the Department of Consumer and Design Sciences at Auburn University. He teaches most of the classes in the financial planning field, and his research interests include racial and gender inequity, financial literacy, and retirement planning.

Morgen Nations is a doctoral student in personal financial planning at Texas Tech University. Her research focuses on the difference between objective and subjective financial knowledge. She can be reached at mnations@ttu.edu.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Americans increasingly consume social media, with roughly 5 percent using some form of it in 2005. By 2020, that number had risen to 72 percent, and over 50 percent of social media users did so daily (Pew Research Center 2021). As the use of social media rises, so does its importance in facilitating engagement and information exchange among diverse groups. Today’s consumers turn to social media to engage with others, and they have relied on it for many modern cultural, political, and economic conversations (Almazrouei, Alshurideh, Al Kurdi, and Salloum 2021; Bolton et al. 2013; Gensler, Völckner, Liu-Thompkins, and Wiertz 2013; Mavrodieva, Rachman, Harahap, and Shaw 2019). Consumers also increasingly use social media to gather information (Jamil et al. 2022; Nam and Hwang 2021) and to form opinions on products and services. Evidence suggests that consumers progressively rely on social media to make financial decisions (Guo, Finke, and Mulholland 2015). Karpenko et al. (2021) found that the most frequently discussed personal finance topics on Reddit, a social media platform, included credit and banking, money management, and real estate. Consumers also use social media to make investment-related decisions, such as buying stocks or cryptocurrency (Guégan and Renault 2021). While social media can provide helpful information, it is also well-documented that this information can mislead consumers. For example, social media has been cited as being partially responsible for facilitating consumers’ frenzy with so-called meme stocks, such as GameStop (Costola, Iacopini, and Santagiustina 2021; Nobanee and Ellili 2023). These types of investments have resulted in significant losses for some unwary consumers. Social media has also played a significant role in attracting investors to the cryptocurrency market (Ante 2023), which has resulted in mixed outcomes for consumers. While some have benefited from investing in cryptocurrencies, others have lost substantially due to the currencies’ volatile nature. This raises investor education and protection concerns as individuals increasingly turn to social media for investment advice. While some investment information on social media outlets has been determined to be high-quality (Tu, Yang, Cheung, and Mamoulis 2018), there is also a great deal of unreliable information. Even so, researchers have found that investors rely on social media advice even when the advice is low in quality (Kadous, Mercer, and Zhou 2022).

Despite the inconsistency in providing quality advice, there is evidence that social media is associated with consumer benefits. For example, research has shown that when social media was used for personal finance, it positively impacted user satisfaction, and some consumers experienced financial gain, which encouraged its continued use (Cao, Gong, and Zeng 2020). Further, the authors found the two most important motivators for using social media for personal finance were its perceived usefulness for making financial decisions and user compatibility with social media. Social media is also associated with helping consumers to build financial literacy (Yanto et al. 2021). Not only does social media influence consumers’ well-being, but consumer behavior on social media platforms can impact investment trends as well as the value, performance, and pricing of assets (Chen, Dong, and Dai 2023; Poongodi, Nguyen, Hamdi, and Cengiz 2021; Tandon, Revankar, Palivela, and Parihar 2021). One study found that investor sentiment on Twitter is associated with returns and trading volume and could provide helpful stock trading information, particularly for small and emerging markets where pertinent information is scarcer (Duz Tan and Tas 2021).

Despite the growing use of social media to make financial decisions, little is known about the characteristics of investors engaging with social media for investment advice. This paper fills this gap by using a nationally representative survey to investigate the demographic, financial, and social characteristics of U.S. investors who use social media as an information source for investing.

Literature Review

Information Sources and Investing

Information search—broadly defined as the process in which consumers reduce uncertainty by seeking out information before making purchase decisions—can be a crucial step in the investing process (Haridasan, Fernando, and Saju 2021). Consumers turn to various sources, such as media, friends and family, the internet, and financial service professionals, to better understand their investment options (Sholin et al. 2021). Moreover, investors may be limited in making decisions based on the actual knowledge they possess (Kahneman 2003). As such, it is essential to understand which information sources investors use, as the influence of information search on consumer decisions can impact the investor’s understanding of finance and the choices an investor may make (Sabri and Aw 2019).

Lin and Lee (2004) noted that consumers who used the internet as a financial source of information were more likely to have a higher level of subjective knowledge, risk tolerance, income, education, and were younger when compared to those who did not use the internet. Conversely, those who sought financial recommendations from a professional were more likely to be older, have lower subjective knowledge, and be less risk tolerant. Those who sought recommendations from friends and family were more likely to be younger and have less subjective knowledge compared to those who did not seek recommendations. Another study found no association between age and the type of information source used for investing (Sholin et al. 2021). However, a positive relationship was found between using a financial professional and higher education levels and receiving financial education in the workplace. Subjective financial knowledge was positively associated with a higher likelihood of doing one’s own investment research (Sholin et al. 2021).

Marwaha and Arora (2016) group information sources into five distinct categories: Media Factor, Recommendation Factor, Analysis Factor, Personal Factors, and Herding Factor. Their study of information source credibility and behavior amongst investors found that Media Factor, which includes sources such as newspapers, the internet, television, and corporate reports, had the highest impact on investor behavior. This is despite consumers ranking the same sources as being only moderately sought out for making financial decisions. This may imply a gap between the information consumers seek and the information that has more influence on consumers. Furthermore, nonprofessional investors may utilize different information sources than professional investors. Maditinos, Ševic, and Theriou (2007) found that while professional investors rely more on technical and fundamental analysis, nonprofessional investors rely more on media and market noise. This furthers the possibility that professional investors, compared to nonprofessional investors, may actively seek information sources requiring a greater understanding of financial markets.

With technological advancements, there has been a notable change in how consumers obtain information about the investment market (Xu, Xuan, and Zheng 2021). Investors have begun to utilize more diverse sources of information. Social media is one such example of technology influencing the information search process.

Social Media and Investing

As with many newer technologies, the early adopters of social media tend to be younger, and several studies have found that younger individuals are more likely to turn to social media as a source of information for financial advice (Cao and Liu 2017; Subramanian and Prerana 2021). This may be due to a plethora of factors, including younger generations being more accepting of using modern technology to manage their finances compared to their older counterparts, holding less investable assets, and feeling intimidated when engaging with a human financial adviser (Brown 2017; Carlin, Olafsson, and Pagel 2019; Silinskas, Ranta, and Wilska 2021). Moreover, younger individuals with less investing experience are more likely to be influenced by social media when considering investing in certain stocks (Gosal, Astuti, and Evelyn 2021). One study found that young adults who use social media for investment decisions are also more likely to spend impulsively (Cao and Liu 2017). At the same time, previous work has indicated the importance of social media as a form of financial literacy communication for younger consumers (Yanto et al. 2021).

One modern source of information, particularly for younger investors, is the “finfluencer” (Tkachenko 2022). Finfluencers are social media influencers who give financial and investing advice to millions of followers through social media sites such as TikTok and YouTube (Place 2022). Mulinda and Niasse (2022) note that this might be partly because younger generations may use social media like a search engine such as Google. While finfluencers with financial accreditations do elicit a more positive response compared to those who do not have such accreditations (Regt, Cheng, and Fawaz 2023), many finfluencers do not obtain the qualifications that are required of financial service professionals (Baker 2022). Research states that consumers can learn from their financial planners (Moreland 2018), which could result in a lower reliance on perhaps less reliable third parties such as social media platforms. Some consumers turn to social media as a substitute for professional services as it is more cost-effective. Yet, the information found therein may not act as an adequate substitute. The rise of finfluencers has led to concerns about promoting ill-advised financial products and spreading financial misinformation (Corbin 2023; Oregon Division of Financial Regulation 2022; Place 2022). Florendo and Estelami (2019) argue that as specific individual characteristics may be positively associated with using social media for financial information, certain groups may be more susceptible to such misinformation.

Social Media and Financial Knowledge

In general, social media users are more likely to have higher levels of general education relative to those who do not use social media (Hruska and Maresova 2020). However, it is also essential to consider the relationship between financial knowledge and social media. Financial knowledge can be measured as subjective and objective knowledge (Carlson, Vincent, Hardesty, and Bearden 2009; Gautam and Jain 2019), which is defined, respectively, as what an individual assumes they know and what an individual knows according to a financial literacy test. Researchers agree that higher levels of objective financial knowledge are preferable (Ansari, Albarrak, Sherfudeen, and Aman 2023; Carlin and Robinson 2012). Bianchi (2018) noted that a higher level of objective financial knowledge was positively associated with a higher annual investment return when controlling for portfolio risk. The same study found that households with higher levels of objective financial knowledge were more likely to keep risk constant when rebalancing their portfolio. Furthermore, these households were more likely to hold higher-risk assets when expected returns were higher (Bianchi 2018).

Higher objective financial knowledge is often linked to greater market participation (van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie 2011). Lower levels of subjective financial knowledge are positively correlated with a higher likelihood of using financial planners, despite being linked to lower market participation (van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie 2011). More simply, an individual with less confidence in their financial knowledge is more likely to seek professional advice while simultaneously being less likely to participate in the financial market. Comparatively, individuals with elevated levels of subjective knowledge are more likely to participate in the financial markets. However, these individuals also are less likely to delegate decisions such as portfolio management to financial professionals (Calcagnoa and Monticone 2015).

Although the relationship between social media use and financial knowledge has been historically under-researched, likely due to the technology’s novelty, some studies imply a link between social media and financial knowledge. For example, posting information on social media about finance, even without reading it, can increase an individual’s subjective knowledge (Ward, Zheng, and Broniarczyk 2023). Additionally, social media use can impact self-esteem, which acts as a mediator between objective and subjective knowledge (Gosal, Astuti, and Evelyn 2021). Estelami and Florendo (2021) note that psychological and demographic information can help determine which groups are more likely to rely on social media to supplement their financial knowledge. For example, the study found that individuals identifying as part of the Republican party were more likely to rely on social media when making financial decisions. Additionally, cognitive style, gullibility, age, gender, and income are other characteristics that may impact one’s reliance on social media for financial advice (Florendo and Estelami 2019). When considering these effects, it becomes apparent that social media usage should be included as part of the information landscape when discussing investment decisions.

Theoretical Framework

Bounded Rationality and Social Media

Bounded rationality theory posits that consumers are limited in their ability to make rational decisions (Simon 2000). While traditional economic theory assumes that market participants are perfectly rational and will utilize all available information when making a decision, bounded rationality accounts for consumers’ limitations in making fully informed decisions (Simon 2000). These limitations could be due to information being too complex for consumers to understand fully, missing information on alternatives, or a lack of certainty about the consequences of the decision. In other words, consumers cannot utilize the information they do not know.

When adding the element of social media, it is vital to consider the computational build of the website, or search engine, as this may exacerbate limited decision-making. Lerman, Hodas, and Wu (2017) noted that the knowledge discovery process may be impacted by the order in which information is prioritized and presented to the viewer. For example, social media content that becomes slightly popular may be further promoted due to the observed popularity, even if the content of the information is lower in quality. Messing and Westwood (2014) echo this sentiment by noting that social media can give individuals access to less-biased information. However, this is only true if the algorithm endorses such an environment. Whether social media introduces information that allows investors to make less-biased decisions—either through “how” or “what” information is presented—may depend on how the websites are programmed to promote information.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Based on the theoretical framework and the literature, the research questions and hypotheses are as follows:

RQ1: What is the association between age and using social media as an information source for investment decisions?

H1: Age is negatively associated with using social media for investment decisions.

RQ2: What is the association between having a lower value of assets to invest and using social media as an information source for investment decisions?

H2: A lower value of assets to invest is associated with using social media for investment decisions.

RQ3: What is the association between objective investment knowledge and using social media as an information source for investment decisions?

H3: Objective investment knowledge is negatively associated with using social media for investment decisions.

RQ4: What is the association between subjective investment knowledge and using social media as an information source for investment decisions?

H4: Subjective financial knowledge is positively associated with using social media for investment decisions.

RQ5: What is the association between using a financial professional and using social media as an information source for investment decisions?

H5: Working with a financial professional is negatively associated with using social media for investment decisions.

Methodology

Data

This study utilized the 2021 National Financial Capability Study (NFCS), which includes data on financial behaviors, attitudes, knowledge, experiences, and financial products and services. Data for the NFCS is collected every three years and comprises two primary surveys: the state-by-state and investor surveys. The 2021 wave of the state-by-state survey includes data on 27,118 U.S. adults across all 50 states and Washington, D.C. The investor survey asks additional questions to 2,824 state-by-state respondents who own investments outside retirement accounts. The state-by-state and investor surveys were merged to examine the dependent variable: social media use for investing decisions. The sample was weighted to be representative of the national population based on age, gender, ethnicity, education, and census division. Weighted estimation was used for descriptive statistics and regression analysis, aligning with recent studies (Kim and Stebbins 2021; Korankye, Pearson, and Salehi 2023; Lee, Hales, and Kelley 2023).

Dependent Variable

The primary dependent variable was operationalized by using responses to the following question: “Which, if any, of the following do you use for information about investing?” Respondents were given 11 choices from which they could have selected any number: YouTube, Facebook, Reddit, TikTok, Instagram, Twitter, Discord, Twitch, Clubhouse, LinkedIn, and Stocktwits. If respondents answered “yes” to using any social media platform, the value was coded as 1, and 0 if they used none. For those who answered “don’t know,” the observations were coded as “0” to maintain more observations. For those who answered “prefer not to say,” the observations were dropped from the analysis. This resulted in a total of 2,061 observations.

Independent Variables

Investor knowledge comprises subjective and objective investor knowledge. Subjective investor knowledge was determined by the following question: “On a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means very low and 7 means very high, how would you assess your overall knowledge about investing?” Those who responded “prefer not to say” were dropped from the analysis. The 2021 NFCS investor survey asked respondents 11 questions related to one’s investment knowledge. One point was allotted for each objective investor knowledge question answered correctly. As such, respondents could have scored between 0 and 11, where 0 denotes low objective investor knowledge, and 11 denotes high objective investor knowledge. Responses of “do not know” were coded as incorrect, and responses of “prefer not to say” were dropped.

Four knowledge categories were created to examine the association between social media use and variations in combined investor objective and subjective knowledge (Enete et al. 2019; Pearson and Korankye 2022; Robb, Babiarz, Woodyard, and Seay 2015): (1) low subjective knowledge / low objective knowledge, (2) low subjective knowledge / high objective knowledge, (3) high subjective knowledge / low objective knowledge, and (4) high subjective knowledge / high objective knowledge. Subjective knowledge was defined as high if respondents scored a 5 or higher on a scale ranging from 1–7 and low if respondents scored 1, 2, 3, or 4. Objective knowledge was defined as high if respondents answered six or more questions correctly and low if respondents answered fewer than six questions correctly.

Financial professional use was determined by answering the question: “How much do you rely on each of the following when making decisions about what to invest in?” Responses with “recommendations from financial professionals who advise you personally” were coded as 1 if respondents replied, “a great deal.” If the respondents chose “not at all,” “somewhat,” or “do not know,” the values were coded as 0. The “prefer not to say” responses were dropped from the sample. Financial education was determined by the question: “Was financial education offered by a school or college you attended or a workplace where you were employed?” If the respondents answered “Yes, and I did participate in the financial education,” the values were coded as 1 and 0 otherwise.

The following question determined investment trading frequency: “In the past 12 months, how many times have you bought or sold investments in non-retirement accounts?” The responses included: none, 1 to 3 times, 4 to 10 times, and 11 times or more. Types of investment assets included individual stocks, individual bonds, mutual funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), annuities (fixed, indexed, or variable), commodities or futures, whole life insurance, REITs, microcap stocks or penny stocks, structured notes, and private placements. Comfort with investing was measured on a scale from 1–10 with the following question: “How comfortable are you when it comes to making investment decisions?” A score of 1 indicated “not at all comfortable,” and 10 indicated “extremely comfortable.” In addition, investors’ motivation for investing was included, and there were six answer choices: (1) to make money in the short term, (2) to make money in the long term, (3) for entertainment/excitement/fun/playing a game, (4) my peers are doing it / social activity / connecting with others, (5) to make a difference in the world / support values I care about / be socially responsible, and (6) to learn about investing.

Race/ethnicity is categorized into four groups: White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian/others. Education included lower than a bachelor’s degree, a bachelor’s degree, and higher than a bachelor’s degree, and the reference group was lower than a bachelor’s degree. Marital status included two groups: married and not married (single, separated, divorced, or widowed). Risk tolerance comprised four groups: (1) not willing to take any financial risks, (2) take average financial risks expecting to earn average returns, (3) take above average financial risks expecting to earn above average returns, and (4) take substantial financial risks expecting to earn substantial returns. If the respondents owned a home, homeownership was coded as 1, and if not, 0. Income and employment were included as categorical variables.

Model

This study utilized the logistic regression via maximum likelihood as follows:

Pr (Y=1)=F(b0+b1 Investor knowlege+

b2 Other financial variables+

b3 Control variables)

Where Y represents the respondents who used social media, investor knowledge stands for objective and subjective investment knowledge. Other financial variables include financial professional use, financial education, investment frequency, types of investments, comfort with investing, and motivation for investing. Control variables include age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, risk tolerance, homeownership, income, investment assets, and employment status.

Results

Descriptive Results

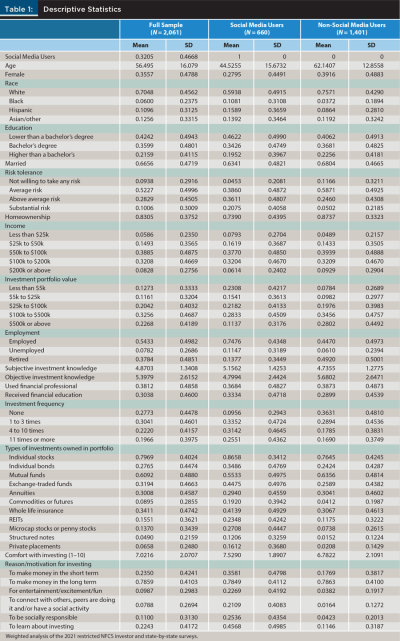

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics. Investors who used social media to make investment decisions comprised about 32 percent of the total sample. They were younger, less likely to be women, racially and ethnically more diverse, and had higher risk tolerance levels than those not using social media. A higher percentage of social media users owned investment portfolios with a value under $5,000 (23 percent) and were currently employed (75 percent) when compared to non-social media users who were mostly retired (49 percent). Social media users had higher subjective investment knowledge (M = 5.16, SD = 1.43) than non-social media users (M = 4.74, SD = 1.28). On the other hand, they had lower objective investment knowledge (M = 4.80, SD = 2.44) than those who did not use social media (M = 5.68, SD = 2.65).

A slightly higher percentage of non-social media users (39 percent) consulted financial planners than social media users (37 percent). Still, more social media users (34 percent) received financial education than non-social media users (29 percent).

Respondents who used social media tended to have higher trading activity than those who did not. For example, 26 percent of social media users bought or sold non-retirement investments 11 times or more in the past 12 months, compared to 17 percent of non-social media users. About 36 percent of non-social media users made no trades in the past 12 months compared to only 10 percent of social media users. About 45 percent of social media users invested in ETFs compared to 26 percent of non-social media users. About 76 percent of non-social media users owned individual stocks, while 87 percent of social media users did. In addition, about 27 percent of social media users invested in microcap stocks or penny stocks, while only 7 percent of non-social media users made these investments.

Social media users reported feeling more comfortable investing (M = 7.53, SD = 1.89) than non-social media users (M = 6.78, SD = 2.11). As for the motivations behind why these consumers were investing, about 23 percent of social media users reported investing for entertainment, excitement, fun, or playing a game, compared to only 4 percent of non-social media users. About 21 percent of social media users invested due to peers, social activity, or connecting with others, compared to only 2 percent of non-social media users. In addition, 25 percent of social media users reported investing to be socially responsible compared to 4 percent of non-social media users. About 46 percent of social media users reported they invested to learn more about investing compared to 11 percent of non-social media users. The greatest motivation among non-social media users was investing for the long term (79 percent).

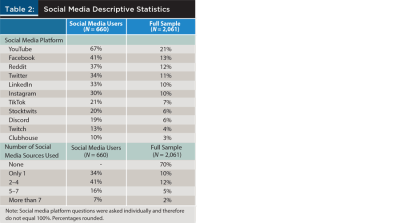

Table 2 shows the percentage of investors using the 11 types of social media platforms included in the survey and the number of platforms investors used. A previous study reported that the top five social media platforms used by U.S. investors to inform their investment decisions were YouTube, Reddit, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (Lin et al. 2022). When looking solely at social media users in the current study, YouTube was the most commonly used social media platform (67 percent) for investment decision-making. Facebook (41 percent) and Reddit (37 percent) were second and third most used. Twitter and LinkedIn were each used by about 33 percent of the sample. Most of the sample (75 percent) used between one and four different social media sources. About 34 percent of the sample used one source, while 41 percent used two to four sources.

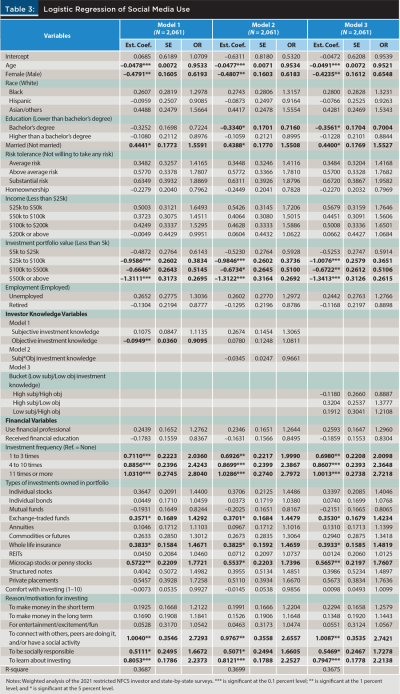

Table 3 shows the results of three logistic regression models for social media use. The main explanatory variables were age, portfolio value, objective investment knowledge, subjective investment knowledge, and financial professional use. Results for Model 1 show that age, portfolio value, and objective investment knowledge were significantly associated with using social media for investment decisions. Specifically, as age increased, investors were less likely to use social media for investment decisions (odds ratio (OR) = 0.95). Owning a portfolio valued over $25,000 was negatively associated with using social media as an investment information source, although income was not significant. Those with higher objective investor knowledge were less likely to use social media for investing (OR = 0.91).

Women were significantly less likely to use social media as an investment information source when compared to men. Women were less likely to use social medial for investment decisions (OR = 0.62). Compared to those with low trading frequencies, those with higher trading frequencies were more likely to use social media. Those who traded 11 times or more in a month had 2.8 times the odds of using social media for investment decision-making compared to those who made no trades monthly. In addition, those who invested in ETFs (OR = 1.43), microcap stocks or penny stocks (OR = 1.77), or who owned whole life insurance (OR = 1.47) were more likely to use social media for investment decisions. Motivations associated with using social media for investing included “investing to learn” (OR = 2.23), being “socially responsible” (OR = 1.67), and “connecting with others” (OR = 2.73).

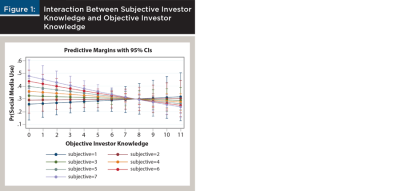

Figure 1 depicts a relationship between subjective and objective investment knowledge. When objective knowledge is lower than 7, those with higher subjective knowledge scores were more likely to use social media; however, when objective knowledge was higher than 8, those with low subjective knowledge had a slightly higher probability of using social media. To investigate whether there was a significant interaction effect between subjective and objective investment knowledge, Model 2 incorporated an interaction term for those variables, which was not significant.

To understand whether there were differences in social media use when looking at respondents’ combined subjective and objective knowledge, the four knowledge categories (high objective / high subjective, high objective / low subjective, etc.) were used in Model 3. No significance was found. In Models 2 and 3, having a bachelor’s degree was negatively associated with using social media for investment advice. Other results from Models 2 and 3 were consistent with Model 1.

Additional Analysis

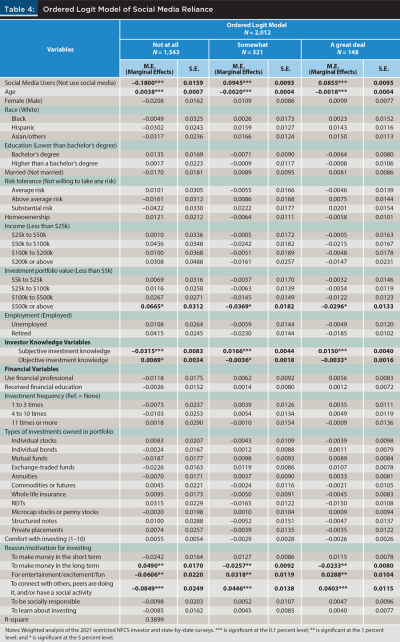

In Models 1–3, the dependent variable, social media use, was operationalized by examining which investors used one of the 11 social media platforms to make investment decisions. However, no information is provided in the survey regarding how frequently these investors used those social media platforms, which could help clarify the differences between casual and heavy social media users. The NFCS survey provides another related question, “How much do you rely on social media groups or message boards where people post investment ideas when making decisions about what to invest in?” While this question asks about social media groups or message boards, a specific type of social media consumption, it can be seen as a proxy for understanding the relationship between how much one uses social media for investment decisions and the related investor characteristics. An ordered logit model was run using the question above as the dependent variable. Of 2,012 respondents, 1,543 stated that they did not use these groups or boards to make investment decisions, while 469 respondents stated they used them “somewhat” or “a great deal.” Those who answered “don’t know” and “prefer not to say” were coded as missing values.

Table 4 shows the marginal effects of the ordered logit model using respondents’ reliance on social media groups or message boards as the dependent variable. As age increased, the probability of using social media groups or message boards decreased by 0.002, and the probability of not using them increased by 0.004, similar to the results seen in Table 3. Compared to those with investment portfolio values lower than $5,000, those with more than $500,000 in assets had a 0.03 lower probability of using social media groups or message boards a great deal. They had a 0.07 higher probability of not using them at all. As subjective knowledge increased, the probability of using social media groups or message boards a great deal increased by 0.02, and the probability of not using them at all decreased by 0.03. However, the probability of using social media groups or message boards a great deal decreased by 0.003 as objective knowledge increased. Respondents who focused on long-term investing had a 0.02 lower probability of using social media groups or message boards a great deal than those who did not focus on long term. The motivations to invest for “excitement and entertainment” and “to connect with others or have a social activity” were positively associated with relying on social media groups or message boards. Unlike in Models 1–3, being female, education level, marriage, trading frequency, type of investments owned, and the motivation to invest “to learn” and “be socially responsible” were not significant.

Discussion and Implications

This study used data from a nationally representative U.S. investor survey to examine the characteristics of individuals who use social media as an information source to make investment decisions. In line with prior literature (Florendo and Estelami 2019), age was negatively associated with using social media for investment decisions, supporting H1. Younger generations tend to accept using modern technology to manage their finances more than older ones. IFA magazine noted that younger investors may become interested in investing due to social media (Tomes 2021). For example, meme stocks, media coverage of events such as the manipulation of GameStop stock, and a sense of gamification may contribute to building interest in young investors through social media. A National Association of Plan Advisors (NAPA) survey also noted that younger individuals turn to investing partly because of the rise in interest in cryptocurrency and an influx of cash during the pandemic (Godbout 2021).

The results also supported H2, which predicted that those who use social media for investment decisions would have lower investment portfolio values than those who do not. However, one study (Filipek, Cwynar, Cwynar, and Pater 2019) found no relation between assets and using social media as an information source for professional investors. While the literature on the relationship between investment portfolio value and social media use is scant, it may be that those with fewer assets are more likely to use social media as an accessible option for financial advice, like with robo-advice (Brenner and Meyell 2020). The use of internet trading platforms is more commonly adopted by younger individuals who generally have lower assets than older individuals; this may be due to social media acting as an inexpensive guide for novice investors (Solanki, Wadhwa, and Gupta 2019).

Hypothesis 3 posited that objective knowledge would be negatively associated with using social media for investment decisions, and this was supported in the results and is in line with previous research (Estelami and Florendo 2021). At the same time, it should not be ignored that social media may positively influence consumers’ objective financial knowledge. Estelami and Florendo (2021) suggest that consumers are less likely to rely on social media for financial decision-making as their financial literacy increases. Hypothesis 4 posited that subjective knowledge would be positively associated with using social media for investment decisions. At a significance level of 0.07, this hypothesis was not supported. However, subjective financial knowledge was significantly and positively associated with relying somewhat or greatly on social media groups or message boards to make investment decisions. Using social media as an information source can be seen as doing one’s own research. Previous work has shown that subjective financial knowledge is positively associated with trusting one’s own investment research (Sholin et al. 2021) and a decreased likelihood of seeking financial advice from a professional (Kramer 2016).

The final hypothesis asserted that using a financial professional would be negatively associated with using social media as an investment information source. However, no evidence was found to support this hypothesis.

There were also findings from the results that were not hypothesized. Social media users were less likely to be women, which is supported by existing literature (Florendo and Estelami 2019). Holding ETFs, whole life insurance, microcap, or penny stocks in one’s investment portfolio was associated with using social media for investing. Additionally, some investing motivations were significantly associated with using social media. Social media users were significantly more likely to invest to connect with others, to be socially responsible, or to learn about investing. Other researchers have also found a link between using social media to learn about personal finance (Cao, Gong, and Zeng 2020).

While the current study addresses a gap in the literature by exploring the characteristics and behaviors of consumers who use social media to make investment decisions, there are a few limitations. “Social media user” was defined as an investor who used one or more social media platforms to seek investment advice, even if they also sought investment advice from a financial professional. There are probably differences between those who strictly use social media and those who use a combination of information sources. Differences may also exist among investors regarding the number and type of platforms they rely on. Future studies should investigate the nuances associated with using specific platforms, such as YouTube versus Twitter, for investment advice. The definition of “financial professionals” is ambiguous in the investor survey. It may refer to an investment adviser, financial planner, or another type of professional. The NFCS only provided data on respondents using social media for non-retirement investment accounts. Future research should include respondents who use social media to make investment decisions in retirement accounts. The data used in this study were collected between June and October of 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. This specific context is important to keep in mind when interpreting the findings. During the pandemic, social media use increased (Nguyen et al. 2020), which may impact the context in which respondents answered survey questions.

Conclusion and Future Research

Social media may be viewed as an alternative way to acquire financial information. However, understanding the impact of modern information sources, such as social media, on investors will likely become more relevant to the success of the financial services industry. This is particularly true for financial planning professionals who will need to navigate this new landscape with clients. One area of interest is the saliency of financial advice and tips provided via social media. To better understand clients’ interests, behaviors, and attitudes, financial professionals could ask clients questions about their social media usage, including which platforms they use and if they use them for investment decision-making. If clients rely heavily upon and are sensitive to information from social media, financial practitioners could consider providing reliable information to help clients overcome emotional bias and undesirable decision-making in the short run. In addition, it is vital to understand whether investors are using social media as a substitute or a complement to professional financial advice. Social media is a marketing tool for many financial advisers; as such, maximizing ways to use it effectively is valuable. Future research should explore how social media impacts consumers’ financial well-being and how professionals in the financial services industry can use social media to better connect with and assist consumers in their financial planning and investment decision-making.

Citation

Reiter, Miranda, Di Qing, and Morgen Nations. 2023. “Who Uses Social Media for Investment Advice?” Journal of Financial Planning 37 (9): 78–99.

References

Almazrouei, Fatima, Muhammad Alshurideh, Barween Al Kurdi, and Said Salloum. 2021. “Social Media Impact on Business: A Systematic Review.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics 2020: 697–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58669-0_62.

Ansari, Yasmeen, Mansour Saleh Albarrak, Noorjahan Sherfudeen, and Arfia Aman. 2023. “Examining the Relationship between Financial Literacy and Demographic Factors and the Overconfidence of Saudi Investors.” Finance Research Letters 52 (March): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103582.

Ante, Lennart. 2023. “How Elon Musk’s Twitter Activity Moves Cryptocurrency Markets.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 186: 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122112.

Baker, Helen. 2022, May 3. “Why You Need to Watch Out for Finfluencers.” Women’s Agenda. https://womensagenda.com.au/life/money/why-you-need-to-watch-out-for-finfluencers%EF%BF%BC/.

Bianchi, Milo. 2018. “Financial Literacy and Portfolio Dynamics.” The Journal of Finance 73 (2): 831–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12605.

Bolton, Ruth, A Parsu Parasuraman, Ankie Hoefnagels, Nanne Migchels, Sertan Kabadayi, Thorsten Gruber, Yuliya Komarova, and Solnet David. 2013. “Understanding Gen Y and Their Use of Social Media: A Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Service Management 24 (3): 245–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231311326987.

Brenner, Lukas, and Tobias Meyell. 2020. “Robo-Advisors: A Substitute for Human Financial Advice?” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 25 (March): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100275.

Brown, Mike. 2017, September 19. “Millennials: Robo-Advisors or Financial Advisors?” LendEDU Blog. https://lendedu.com/blog/robo-advisors-vs-financial-advisors/.

Calcagno, Riccardo, and Chiara Monticone. 2015. “Financial Literacy and the Demand for Financial Advice.” Journal of Banking & Finance 50 (January): 363–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.03.013.

Cao, Yingxia, Fengmei Gong, and Tong Zeng. 2020. “Antecedents and Consequences of Using Social Media for Personal Finance.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 31 (1): 162–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/JFCP-18-00049.

Cao, Yingxia, and Jeanny Liu. 2017. “Financial Executive Orientation, Information Source, and Financial Satisfaction of Young Adults.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 28 (1): 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1891/1052-3073.28.1.5.

Carlin, Bruce, Arna Olafsson, and Michaela Pagel. 2019. “Generational Differences in Managing Personal Finances.” AEA Papers and Proceedings 109 (May): 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191011.

Carlin, Bruce, and David T. Robinson. 2012. “What Does Financial Literacy Training Teach Us?” The Journal of Economic Education 43 (3): 235–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2012.686385.

Carlson, Jay P., Leslie H. Vincent, David M. Hardesty, and William O. Bearden. 2009. “Objective and Subjective Knowledge Relationships: A Quantitative Analysis of Consumer Research Findings.” Journal of Consumer Research 35 (5): 864–76. https://doi.org/10.1086/593688.

Chen, Rongjuan, Rouxo Dong, and Yichao Dai. 2023. “The Relationship Between Twitter Sentiment and Stock Performance: A Decision Tree Approach.” In Proceedings of the 56th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences: 4850–59. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/103225.

Corbin, Kenneth. 2023, March 2. “FINRA Warns Brokerage Firms on Risks Related to ‘Finfluencers.’” Barron’s. www.barrons.com/advisor/articles/finra-finfluencers-advisors-33736bae.

Costola, Michele, Matteo Iacopini, and Carlo Santagiustina. 2021. “On the ‘Mementum’ of Meme Stocks.” Economics Letters 207: 110021.

Duz Tan, Selin, and Oktay Tas. 2021. “Social Media Sentiment in International Stock Returns and Trading Activity.” Journal of Behavioral Finance 22 (2): 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2020.1772261.

Enete, Shane, Miranda Reiter, Wendy Usrey, Andrew Scott, and Martin Seay. 2019. “Who Is Investing in ETFs? Exploring the Role of Investor Knowledge.” Journal of Financial Planning 32 (7): 44–53.

Estelami, Hooman, and Jenna Florendo. 2021. “The Role of Financial Literacy, Need for Cognition and Political Orientation on Consumers’ Use of Social Media in Financial Decision-making.” Journal of Personal Finance 20 (2): 57–73.

Filipek, Kamil, Wiktor Cwynar, Andrzej Cwynar, and Robert Pater. 2019. “Social Media as an Information Source in Finance: Evidence from the Community of Financial Market Professionals in Poland.” The International Journal of Digital Accounting Research 19 (March): 29–58. https://doi.org/10.4192/1577-8517-v19_2.

Florendo, Jenna, and Hooman Estelami. 2019. “The Role of Cognitive Style, Gullibility, and Demographics on the Use of Social Media for Financial Decision-making.” Journal of Financial Services Marketing 24 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-019-00064-7.

Gautam, Shalini, and Kokil Jain. 2019. “Dynamics of Objective and Subjective Financial Knowledge on Financial Behaviour.” Abhigyan 37 (1): 11–20. https://doi.org/10.56401/Abhigyan/37.1.2019.11-20.

Gensler, Sonja, Franziska Völckner, Yuping Liu-Thompkins, and Caroline Wiertz. 2013. “Managing Brands in the Social Media Environment.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 27 (4): 242–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2013.09.004.

Godbout, Ted. 2021, September 3. “Young Adults, Minorities Lean on Social Media for Investing.” National Association of Plan Advisors. www.napa-net.org/news-info/daily-news/young-adults-minorities-lean-social-media-investing.

Gosal, Rex, Dewi Astuti, and Evelyn Evelyn. 2021. “Influence of Self-Esteem and Objective Financial Knowledge on the Financial Behavior in Young Adults with Subjective Financial Knowledge Mediation as Variable.” International Journal of Financial and Investment Studies 2 (2): 56–64. https://doi.org/10.9744/ijfis.2.2.56-64.

Guégan, Dominique, and Thomas Renault. 2021. “Does Investor Sentiment on Social Media Provide Robust Information for Bitcoin Returns Predictability?” Finance Research Letters 38 (January): 101494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2020.101494.

Guo, Tao, Michael Finke, and Barry Mulholland. 2015. “Investor Attention and Advisor Social Media Interaction.” Applied Economics Letters 22 (4): 261–65.

Haridasan, Anu, Angeline Gautami Fernando, and B. Saju. 2021. “A Systematic Review of Consumer Information Search in Online and Offline Environments.” RAUSP Management Journal 56 (2): 234–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-08-2019-0174.

Hruska, Jan, and Petra Maresova. 2020. “Use of Social Media Platforms among Adults in the United States—Behavior on Social Media.” Societies 10 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10010027.

Jamil, Khalid, Liu Dunnan, Rana Faizan Gul, Muhammad Usman Shehzad, Syed Hussain Mustafa Gillani, and Fazal Hussain Awan. 2022. “Role of Social Media Marketing Activities in Influencing Customer Intentions: A Perspective of a New Emerging Era.” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (January): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.808525.

Kadous, Kathryn, Molly Mercer, and Yuepin Zhou. 2022. “Why Do Investors Rely on Low-Quality Investment Advice? Experimental Evidence from Social Media Platforms.” Working paper, Emory University. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2968407.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2003. “Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics.” The American Economic Review 93 (5): 1449–75. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803322655392.

Karpenko, Valeriya, Kirill Mukhina, Daria Rybakova, Irina Busurkina, and Denis Bulygin. 2021. “A Study of Personal Finance Practices. The Case of Online Discussions on Reddit.” In IMS 2021—International Conference “Internet and Modern Society”: 206–211. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3090/spaper19.pdf.

Kim, K.T. and Rich Stebbins. 2021. “Everybody Dies: Financial Education and Basic Estate Planning.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 32 (3): 402–416.

Korankye, Thomas, Blain Pearson, and Hossein Salehi. 2023. “The Nexus Between Investor Sophistication and Annuity Insurance Ownership: Evidence from FINRA’s National Financial Capability Study.” Managerial Finance 49 (2): 398–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-04-2022-0169.

Kramer, Marc M. 2016. “Financial Literacy, Confidence and Financial Advice Seeking.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 131 (November): 198–217.

Lee, Y., E. Hales, and H. Kelley. 2023. “Financial Behaviors, Government Assistance, and Financial Satisfaction.” Social Indicators Research 166 (1): 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205–022–03051-z.

Lerman, Kristina, Nathan Hodas, and Hao Wu. 2017, September 30. “Bounded Rationality in Scholarly Knowledge Discovery.” ArXiv: 1–23. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1710.00269.

Lin, Judy, Christopher Bumcrot, Gary Mottola, Olivia Valdes, and Gerri Walsh. 2022. “The Changing Landscape of Investors in the United States: A Report of the National Financial Capability Study.” FINRA Investor Education Foundation. www.FINRAFoundation.org/Investor-Report2021.

Lin, Qihua “Catherine,” and Jinkook Lee. 2004. “Consumer Information Search When Making Investment Decisions.” Financial Services Review 13 (4): 319–32.

Maditinos, Dimitrios I., Željko Ševic, and Nikolaos G. Theriou. 2007. “Investors’ Behaviour in the Athens Stock Exchange (ASE).” Studies in Economics and Finance 24 (1): 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/10867370710737373.

Marwaha, Kanika, and Sangeeta Arora. 2016. “Information Sources Credibility and Its Impact on Individual Investor Behavior: An Empirical Analysis.” Rai Management Journal 13 (1): 14–23.

Mavrodieva, Alexandrina, Okky Rachman, Vito Harahap, and Rajib Shaw. 2019. “Role of Social Media as a Soft Power Tool in Raising Public Awareness and Engagement in Addressing Climate Change.” Climate 7 (10): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7100122.

Messing, Solomon, and Sean Westwood. 2014. “Selective Exposure in the Age of Social Media: Endorsements Trump Partisan Source Affiliation When Selecting News Online.” Communication Research 41 (8): 1042–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212466406.

Moreland, Keith A. 2018. “Seeking Financial Advice and Other Desirable Financial Behaviors.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 29 (2): 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1891/1052-3073.29.2.198.

Mulinda, Norah, and Amina Niasse. 2022, July 29. “Gen Z Uses TikTok Like Google, Upsetting the Old Internet Order.” Bloomberg. www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-29/gen-z-uses-tiktok-like-google-upsetting-the-old-internet-order.

Nam, Su-Jung, and Hyesun Hwang. 2021. “Consumers’ Participation in Information-Related Activities on Social Media.” PLoS ONE 16 (4): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250248.

Nobanee, Haitham, and Nejla Ould Daoud Ellili. 2023. “What Do We Know about Meme Stocks? A Bibliometric and Systematic Review, Current Streams, Developments, and Directions for Future Research.” International Review of Economics & Finance 85 (May 2023): 589–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2023.02.012.

Nguyen, Minh Hao, Jonathan Gruber, Jaelle Fuchs, Will Marler, Amanda Hunsaker, and Eszter Hargittai. 2020. “Changes in Digital Communication During the COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Implications for Digital Inequality and Future Research.” Social Media + Society 6 (3): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120948255.

Oregon Division of Financial Regulation. 2022, October 19. “Division of Financial Regulation: DFR Warns Investors to Not Chase Crypto, Market Losses through Online Scams and ‘Finfluencers’: 2022 News Releases: State of Oregon.” Oregon Division of Financial Regulation. https://dfr.oregon.gov/news/news2022/Pages/20221019-crypto-scam-finfluencers.aspx.

Pearson, Blain, and Thomas Korankye. 2022. “The Association Between Financial Literacy Confidence and Financial Satisfaction.” Review of Behavioral Finance. Preprint, accepted in 2022. https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-03-2022-0090.

Pew Research Center. 2021. “Social Media Fact Sheet.” www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/.

Place, Nathan. 2022, August 18. “Social Media’ finfluencers’ Are Misleading Investors: Young Investors Are Increasingly Turning to TikTokers and YouTubers for Stock Tips, Often with Bad Results.” Financial Planning. www.financial-planning.com/news/beware-the-finfluencer-how-social-media-stars-are-misinforming-young-investors.

Poongodi, Manoharan, Tu Nguyen, Mounir Hamdi, and Korhan Cengiz. 2021. “Global Cryptocurrency Trend Prediction using Social Media.” Information Processing & Management 58 (6): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102708.

Regt, Anouk de, Zixuan Cheng, and Rayan Fawaz. 2023. “Young People Under ‘Finfluencer’: The Rise of Financial Influencers on Instagram: An Abstract.” In Optimistic Marketing in Challenging Times: Serving Ever-Shifting Customer Needs. Edited by Bruna Jochims and Juliann Allen. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland: 271–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24687-6_106.

Robb, Cliff A., Patryk Babiarz, Ann Woodyard, and Martin C. Seay. 2015. “Bounded Rationality and Use of Alternative Financial Services.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 49 (2): 407–435.

Sabri, Mohamad Fazli, and Eugene Cheng-Xi Aw. 2019. “Financial Literacy and Related Outcomes: The Role of Financial Information Sources.” International Journal of Business and Society 20 (1): 286–98.

Sholin, Travis, HanNa Lim, Miranda Reiter, Efthymia Antonoudi, and Meghaan Lurtz. 2021. “Money Scripts Related to the Use and Trust of Investment Advice.” Journal of Financial Therapy 12 (2): 47–71. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944–9771.1272.

Silinskas, Gintautas, Mette Ranta, and Terhi-Anna Wilska. 2021. “Financial Behaviour Under Economic Strain in Different Age Groups: Predictors and Change Across 20 Years.” Journal of Consumer Policy 44 (2): 235–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-021-09480-6.

Simon, Herbert A. 2000. “Bounded Rationality in Social Science: Today and Tomorrow.” Mind & Society 1 (1): 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02512227.

Solanki, Shivani, S Wadhwa, and Shipra Gupta. 2019. “Digital Technology: An Influential Factor in Investment Decision-making.” International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology 8 (December): 27–31. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijeat.F1007.1186S419.

Subramanian, Yavana R., and M. Prerana. 2021. “Social-Media Influence on the Investment Decisions Among the Young Adults in India.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Management and Technology 2 (1): 17–26. https://doi.org/10.46977/apjmt.2021v02i01.003.

Tandon, Chahat, Sanjana Revankar, Hemant Palivela, and Sidharth Parihar. 2021. “How Can We Predict the Impact of the Social Media Messages on the Value of Cryptocurrency? Insights from Big Data Analytics.” International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 1 (2): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2021.100035.

Tkachenko, Tim. 2022, August 23. “Why Companies Should Learn from the Rise of the ‘Finfluencer.’” World Economic Forum. www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/08/finfluencer-gen-z-financial-advice/.

Tomes, Rebecca. 2021, November 6. “1 in 5 Investors Are Only Using Social Media to Research New Investments.” IFA. https://ifamagazine.com/article/1-in-5-investors-are-only-using-social-media-to-research-new-investments/.

Tu, Wenting, Min Yang, David W. Cheung, and Nikos Mamoulis. 2018. “Investment Recommendation by Discovering High-Quality Opinions in Investor Based Social Networks.” Information Systems 78 (November): 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.is.2018.02.011.

van Rooij, Maarten, Annamaria Lusardi, and Rob Alessie. 2011. “Financial Literacy and Stock Market Participation.” Journal of Financial Economics 101 (2): 449–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.006.

Ward, Adrian F., Jianqing Zheng, and Susan M. Broniarczyk. 2023. “I Share, Therefore I Know? Sharing Online Content—Even without Reading It—Inflates Subjective Knowledge.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 33 (3): 469–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1321.

Xu, Yongxin, Yuhao Xuan, and Gaoping Zheng. 2021. “Internet Searching and Stock Price Crash Risk: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment.” Journal of Financial Economics 141 (1): 255–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.03.003.

Yanto, Heri, Norashikin Ismail, Kiswanto Kiswanto, Nurhazrina Mat Rahim, and Niswah Baroroh. 2021. “The Roles of Peers and Social Media in Building Financial Literacy among the Millennial Generation: A Case of Indonesian Economics and Business Students.” Edited by Guangchao Charles Feng. Cogent Social Sciences 7 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1947579.