Journal of Financial Planning: November 2016

The past 30 years have seen massive changes in the competencies and perspectives of the financial planning profession. What was cutting-edge or unthinkable in the mid-1980s is now commonplace in the work of financial planners. Fee-only planning has blossomed, the fiduciary standard is about to become a required rule for retirement advisers, and same-sex marriage and civil unions have become accepted legal relationships. Communication skills are now well-established competencies for the profession, including assessment within the CFP® certification examination.

What most planners do not realize is that the literature on building trust and enhancing communication skills is based on serving typical North American clients.1 Those clients will change in the coming years, so planners need to look ahead to a broader range of skills that fit the clients of tomorrow.

The World Is Changing

The demographics of the United States and Canada are changing rapidly as the world becomes more global. Newcomers from China and India are now outpacing immigrants from Central and South America in most areas of the U.S.2 Global upper-middle-class and wealthy families are sending their children to North American schools to be educated. These families are buying homes at breakneck pace in places like Los Angeles, New York, Miami, and Vancouver. Cross-cultural marriages are increasing, as are blended families with cross-cultural connections. The next frontier for skills in financial planning is in understanding and helping the cross-cultural client.

The Hidden Role of Culture

Financial planners are generally encouraged to do the following with their clients:

- Venture in a forthright way into clients’ personal and family finances, issues, and plans;

- Assume the individual client in front of you is the primary decision-maker for his own life. If you are doing planning that involves others, get them into meetings so they can speak for themselves and ask their own questions;

- Use active listening techniques to elicit clients’ feelings and uncover areas blocking decision-making;

- Use clarifying questions in a sensitive yet direct way to probe the issues facing the client;

- Establish trust from the very first meeting by showing you are reliable, safe, and confidential.

The problem is that each of these skills can backfire with clients raised outside Western cultures. Consider these scenarios that you may encounter in coming years, if you haven’t already experienced them:

A new client couple is a female American business owner and her husband, a consultant from India whom she met at a conference. They are in need of financial planning for their combined net worth of $2.3 million. She appreciates your structured interview and attention to personal concerns. He is surprised she is willing to disclose their personal information so quickly without spending time to get to know you first. He talks more about how their wealth will assist multiple members of his family back in India—something she sees as a threat to their personal financial stability. The husband argues with his wife actively in front of you and expects you to support his viewpoint. When you try to remain neutral, he dismisses you as having no expertise or values.

A young Middle Eastern man, educated in the United States with the support of his faraway family, is referred for financial planning and investment advice by his supervisor in the technology industry where he is making his first six-figure salary. As you move through your normal onboarding process, he takes each form home to scan and email to his father, three uncles, and four cousins for their comments. You feel frustrated and mistrusted, wondering if all this hassle is worth it. This process also triples the time you normally have budgeted to deal with such matters.

A prosperous medical practice that is one of your best clients recruits a young doctor and his wife from China. He is recommended to you as he begins building his wealth. At the first interview, you follow well-established procedures of asking open-ended questions about him and his wife, you reflect your sense of his feelings, and you probe for life goals and dreams. You also emphasize that your normal procedure is to include spouses in any planning. The young physician nods and smiles throughout the interview, apparently agreeing with your excellent suggestions. At meeting’s end, when offered an initial client agreement, he says he would like to take the paperwork home to review but is sure he will sign it. Two days later, you get an angry call from the managing partner of the medical practice who asks what went wrong with the meeting. Apparently the young physician was offended at your asking inappropriately personal questions, you suggested he was a weak leader of his own family, and you rushed him to sign papers. The partner wonders if something has happened to your effectiveness with new clients.

These examples are hints of what is coming. Approaching things from your normal perspective may not be effective with potential or current clients from other cultures.

Understanding Global Cultures Using a Simplified Scheme

How then, can planners get educated for cross-cultural clients? It would be overwhelming to learn what each global culture is and how to approach the financial needs of its members. Fortunately, researchers in cross-cultural psychology and sociology have recently begun to organize global patterns into three core styles.3

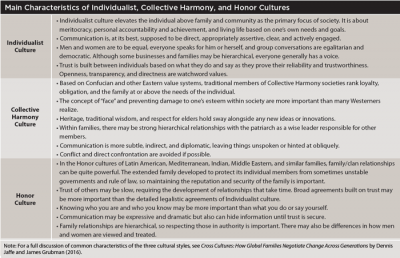

In our 2016 book, Cross Cultures: How Global Families Negotiate Change Across Generations, we discuss these styles using easily understood labels in the context of the financial lives of families:

Individualist Culture: typically considered the Western culture of Northern Europe, the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and societies that originate in those areas.

Collective Harmony Culture: typically considered Eastern culture, focused on China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, Korea, parts of Indonesia, and the societies that originate there.

Honor Culture: a new classification that draws together the core elements of apparently disparate cultures from Latin America, the Middle East, Southern and Eastern Europe, Africa, Russia, and India.

It is not that every client from each culture will always demonstrate the beliefs or customs summarized in the table above. People are individuals with complex mixtures of behaviors. However, being culturally intelligent will help you understand and advise all of your clients, not just the clients you most identify with in your practice.4

The Three Global Cultures and the Future of Planning

Understanding the three cultures and their various blends in individual families and clients can help financial planners make adjustments in their thinking and behavior. If you were raised in the Individualist culture of North America, you may be used to certain assumptions and behaviors such as being direct, egalitarian, and able to discuss personal issues relatively openly. In contrast, when dealing with some individuals from Collective Harmony or Honor cultures, you may need to respect the following assumptions and behaviors:

Strive to understand how individual needs and interests relate to their family interests. Ask about who else in the family needs to be asked about any financial planning that may occur. You may even need to invite in family elders if the clients are very closely connected to their family.

Take more time than usual in building the relationship with the client and his or her family (particularly patriarchs if the family is strongly hierarchical). Share personal details of your own family and values, and be patient in developing trust. Don’t rush the process.

Some clients will want to discuss broad-brush plans before they work out all the fine details. You have compliance issues to be addressed, but these clients may experience reams of paperwork as unnecessary, overwhelming, or even suspicious. Take time to explain the necessity for laying out legalistic details.

Do not assume agreement even if the client seems to be in favor of what you are saying. Listen carefully, allow time for objections to surface, and be sure that their words and actions match. Some traditional Honor or Harmony clients see open disagreement as confrontational or potentially embarrassing. Make room for drawing out concerns gently and respectfully.

Start with core values and principles rather than explaining procedures. Some cultures prefer to hear the reasoning behind recommendations first and in detail, while many Individualist clients are ready to accept recommendations if they are provided with an overview of the “why.”

Be careful of making assumptions about marriages and relationships. Traditional Honor or Harmony couples may defer to the male spouse more than you may be used to with Individualist couples. Offer to include spouses and children but observe whether this seems disrespectful.

Be careful when probing about personal or family issues, especially before a deep sense of trust has been built. What Individualist clients understand as normal professional inquiry may be experienced by Honor or Harmony clients as intrusive.

Use indirect talk about concerns and issues with cross-cultural clients if necessary. Tell stories of other families who may have similar needs or problems due to similar life circumstances. If your client is interested and offers confirming personal details, see that as evidence you are on the right track.

Many cultures see interrupting as rude. They avoid stepping in too quickly when someone else is talking. Make room for the client to ponder and reply to your points. When they speak, listen carefully and wait before replying.

Your practice may not yet have many cross-cultural clients, so you may not be able to relate to the recommendations shared here. Yet, just as the past 30 years demonstrated the need to prepare for seemingly unlikely changes in society and the profession, now is the time to begin learning about the world about to enter your business in the coming decades.

James Grubman, Ph.D., has provided services to individuals, couples, and families of wealth for more than 30 years. He often is consulted in situations of complexity where psychology, law, finance, medicine, and business all come into play to varying degrees. He draws on his experience as a psychologist, neuropsychologist, and family business consultant with specialty interests in trusts and estate law, family governance, and wealth psychology.

Dennis T. Jaffe, Ph.D., is a San Francisco-based adviser to families about family business, governance, wealth, and philanthropy. He is author or co-author of several books, including the 2016 title Cross Cultures: How Global Families Negotiate Change Across Generations. He has a Ph.D. in sociology from Yale University and is professor emeritus of organizational systems and psychology at Saybrook University.

Endnotes

- Now-classic examples include: “Specific Elements of Communication that Affect Trust and Commitment in the Financial Planning Process,” by Deanna L. Sharpe, Carol Anderson, Andrea White, Susan Galvan, and Martin Siesta published in 2007 in Financial Counseling and Planning, Vol. 18, Issue 1; “Communication Issues in Life Planning: Defining Key Factors in Developing Successful Planner-Client Relationships,” by Carol Anderson and Deanna L. Sharpe, a white paper published in 2007 by FPA Press; and “The Changing Role of the Financial Planner Part I: From Financial Analytics to Coaching and Life Planning,” by David Dubofsky and Lyle Sussman published in the August 2009 issue of the Journal of Financial Planning.

- See “Immigration Source Shifts to Asia from Mexico,” by Janet Adamy and Paul Overberg in the September 7, 2016 issue of The Wall Street Journal, available at www.wsj.com/articles/immigration-source-shifts-to-asia-from-mexico-1473205576.

- See “Within- and Between-Culture Variation: Individual Differences and the Cultural Logics of Honor, Face, and Dignity Cultures,” by Angela Leung and Dov Cohen published in the March 2011 issue of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology; and Negotiating Globally, third edition, a 2014 book by Jeanne M. Brett.

- For more on being culturally intelligent, see “Cultural Intelligence,” by P. Christopher Earley and Elaine Mosakowski published in the October 2004 issue of Harvard Business Review, available at hbr.org/2004/10/cultural-intelligence.

Sidebar:

How To Prepare for the Next Wave in Financial Planning

You can begin preparing for an increasingly global environment by using helpful resources, including:

- The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business

by Erin Meyer (PublicAffairs, 2014) - HBR’s 10 Must Reads on Managing Across Cultures, with featured article “Cultural Intelligence” by P. Christopher Earley and Elaine Mosakowski

(Harvard Business Review, 2016) - Cross Cultures: How Global Families Negotiate Change Across Generations

by Dennis T. Jaffe and James Grubman (FamilyWealth Consulting, 2016)

Learn More

Join us for a Journal in the Round virtual roundtable discussion with key Journal contributors on client trust and communication topics.

• December 2, 2016

• 2 p.m., Eastern

Learn more and register here.