Journal of Financial Planning: August 2020

Nick Follet is manager, fixed income, at Commonwealth Financial Network®, member FINRA/SIPC, a registered investment adviser.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

Markets rise and fall, but when they fall at an unprecedented rate and then rise just as quickly, it’s difficult to make sense of what’s going on. These circumstances are further compounded by the fact that, as of this writing, we don’t know how the drivers of the market—namely, the coronavirus crisis and resulting economic damage—will resolve. Timing the market requires two right decisions: when to leave and when to reenter. We’ve all seen the cost of missing out on the rebound, but staying invested and disciplined during a historic market correction, global pandemic, and recession—all happening concurrently—is easier said than done.

When the Dow posted its five largest daily point losses in history within the span of 10 days, many investors may have felt as if their portfolios were in free fall. The obvious solution was to pull the rip cord and open their parachute. The ensuing panic seemed to overshadow all notions of preparing a proper strategy in advance to achieve as soft a landing as possible, given the unpredictable nature of the market and the idea that what goes up must come down.

Emotions manifested differently among advisers and their clients in how they approached their investments, with some interesting, but perhaps not surprising, lessons learned.

Too Much Confidence Can Leave You Missing Out

Overconfidence. We all know someone with this emotional bias. They believe they know more than they do or have an outsized degree of certainty that a particular outcome will be achieved. Studies have found that investors generally expect their portfolios to outperform the market in any given year.1 Yet DALBAR found that while the S&P 500 lost 4.38 percent in 2018, the average equity investor lost nearly 9.5 percent.2 This pattern has held up over longer periods as well. Overconfidence can lead to more snap decisions and more trading volume. Some studies have concluded that there’s a strong correlation between turnover rates (how often one trades their portfolio) and lower returns.3

The fourth quarter of 2018 proved a good example of this theory. Not only was this the worst quarter of 2018 for the S&P 500, seeing a decline of 13.52 percent, but it was also the quarter with the highest trading volume. It’s no coincidence that five out of the six best days for the index also occurred in the fourth quarter. Investors who reshuffled portfolios had a higher likelihood of missing out on these crucial days, exacerbating losses. Missing out on just Dec. 26, 2018, penalized investors by nearly 5 percent.

Resisting the urge to overtrade and overestimate the quality of your information can pay dividends over longer time frames. When you expand those numbers to the 2020 bear and bull markets, the numbers are even more exaggerated. Peak to trough lasted just over one month and inflicted more than 30 percent in investment losses in the broad U.S. market. Since then, the market has recovered most of those losses. The book has not yet been written on this market cycle, so it remains to be seen where and when we will ultimately end up, but one thing is certain—it’s best to buy low and sell high rather than the reverse.

Rebalancing During a Sell-Off Can Lead to a Faster Recovery

One of the more important decisions in creating a portfolio is investment allocation. But like a garden, you can’t just plant the seeds and move on; you need to tend to the investment over time. During bear markets, equities typically sell off more than bonds, and a 60/40 portfolio (assuming an equity component of 45 percent domestic and 15 percent international) would have seen its allocation shift to roughly 50/50 between January and the third week of March this year. After such a historic sell-off, it’s difficult psychologically to rebalance a portfolio and put more back in the very component that was losing the most amount of money in the first place.

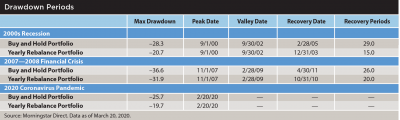

Risk aversion in the middle of a downturn is completely understandable, but it may also be unwarranted. Morningstar recently released a study4 showing that a portfolio rebalanced yearly outperformed a buy-and-hold strategy by an average of 6 percent during the last three recessions. It reduced the recovery period significantly as well (see the table on this page).

It’s tough to sell what’s working only to buy what isn’t, but rebalancing is a good way to rein in overly allocated portfolios, systematically address loss aversion, and check in on the risk tolerance of the portfolio as a whole.

Forgetting About Risk Can Be Risky

Through March and April, Commonwealth’s Investment Management and Research team saw a sharp spike in questions from advisers related to speculative investment ideas. The calls started at the beginning of March, when equity markets began to decline. Excessive risk-taking and greed were common themes during that time, while the due diligence process became a victim of market exuberance.

Buy decisions on speculative investments—oil futures products, in particular—seemed to be quick and irrational in some cases. For example, one adviser purchased an oil futures exchange-traded note and then called the next day to see what was happening after it fell 40 percent. So too have we seen a pickup in inverse leveraged exchange-traded funds since the market started to rebound. To paraphrase Daniel Kahneman, people are often blind to their own blindness.

Quality Can Provide Downside Protection When Markets Don’t Behave as Expected

In March, when equities were selling off, the bond market failed to be the ballast it is traditionally expected to be. While it’s shocking but understandable that the S&P 500 could be down almost 20 percent in two weeks’ time, it’s both shocking and almost inconceivable that the main bond index (the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index) would be down almost 7 percent in the same period. The psychological impact of seeing red simultaneously in fixed income and equities was a difficult hurdle to get over.

As the bond allocation wasn’t working as it should in his defensive portfolio model, one adviser decided he was going to remove the fixed income holdings that were most likely to decline even further. In his words, he was willing to give up what he deemed a maximum upside of 4 percent to 5 percent to forego any downside. Instead, he was going to take his risk with stocks. He was willing to lock in some losses in his most aggressive fixed income positions and rebalanced the nonequity portion of the portfolio exclusively in high-grade bond funds.

The tricky part of the equation was articulating his decision to clients invested in this portfolio and keeping them updated on how he planned to redeploy into the market. By and large, the approach has worked. While some of the funds have bounced back, his bias to quality and the general thesis of avoiding risk in the fixed income market has worked out to his clients’ satisfaction.

Thinking Things Through

Fear of the unknown is innately human, and with the number of unknowns increasing seemingly by the day, well-

placed concern and consternation can turn into outright panic. By having a well-thought-out plan in advance and being cognizant of biases, advisers and investors can better position themselves for success, no matter the market.

Endnotes

- See “Boys Will Be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment,” by Brad Barber and Terrance Odean in the February 2001 issue of The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Available at faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/odean/papers/gender/BoysWillBeBoys.pdf.

- See the March 25, 2019 DALBAR press release, “Average Investor Blown Away by Market Turmoil in 2018.” Available at dalbar.com/Portals/dalbar/Cache/News/PressReleases/QAIBPressRelease_2019.pdf.

- For example, see endnote No. 1.

- See “Here’s Why You Should Rebalance (Again),” by Adam Millson and Jason Kephart, CFA, posted March 26, 2020 at morningstar.com/articles/974578/heres-why-you-should-rebalance-again.