Journal of Financial Planning: August 2021

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Abstract: The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act includes debt relief measures on Education Department-owned federal student loans. Effective March 13, 2020, student loan interest rates were reduced to zero, student loan payments have been suspended, and collection actions of defaulted loans ceased. The provisions are currently set to expire on September 30, 2021. Alternatives available to borrowers of eligible student loans for taking advantage of the provisions are analyzed.

Nell S. Gullett, D.B.A., is professor of finance in the College of Business and Global Affairs at the University of Tennessee at Martin. Gullett can be reached HERE.

Mahmoud M. Haddad, Ph.D., is professor of finance in the College of Business and Global Affairs at the University of Tennessee at Martin.

Laura G. Hatch, CPA, is lecturer of accounting in the College of Business and Global Affairs at the University of Tennessee at Martin.

Borrowers are expected to repay loans as contractually agreed. Failure to do so will trigger negative consequences including assessment of late fees, imposition of penalty interest rates, wage garnishments, collection agency actions, and credit score reductions by the credit bureaus. But 2020 and 2021 have proven to be extraordinary years, and making loan payments as scheduled may not be the best financial strategy.

On March 13, 2020, President Donald Trump declared a national emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Two weeks later, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was passed by Congress, providing $2 trillion of assistance to U.S. households and businesses to offset some of the catastrophic loss of employment and income. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 20.4 million nonfarm jobs were lost in March and April of 2020.1 The unemployment rate rose from 3.5 percent in February to 4.4 percent in March to 14.7 percent in April. Unemployment for May was 13.3 percent, and the rate continued to decrease each month. The year ended with an unemployment rate for December 2020 of 6.7 percent.2 A Bankrate survey from June 2020 reports 49 percent of U.S. adults said their income had been reduced due to the coronavirus pandemic and the economic shutdown (Foster 2020).

The CARES Act provided direct stimulus payments to households, new supplemental unemployment insurance benefits, and an assortment of loans and grants to businesses. It has numerous additional provisions to help households cope with the economic devastation due to the abrupt economic shutdown, including debt relief measures on Education Department-owned federal student loans. Student loan debt for 2020 totaled $1.56 trillion owed by 44.7 million borrowers for an average of $32,731 per borrower. It is the second largest type of consumer debt, after mortgages (Friedman 2020). Specifically, student loan interest rates were reduced to zero, student loan payments have been suspended, and collection actions of defaulted loans ceased. The student loan provisions took effect on March 13, 2020, and were originally set to expire on September 30, 2020, in anticipation of the pandemic winding down by the end of 2020. The emergency relief measures have been extended through September 30, 2021, as the pandemic has continued to wreak havoc well into 2021 and could be extended further.

Borrowers of eligible student loans should consider how to maximize the benefits of the CARES Act student loan provisions from March 13, 2020, through September 30, 2021. For this 18-month period, borrowers will not suffer the negative consequences of nonpayment. Some may wish to continue to make payments as originally scheduled, but borrowers should also consider strategies of nonpayment during this “protected” time period. For someone who has lost income or employment, take advantage of this temporary relief of financial pressure. In lieu of making the monthly student loan payments, redirect the equivalent monthly payment to high-priority needs such as housing, food, or medical expenses. If the borrower’s income continued through the pandemic, the equivalent student loan payments can be used to achieve the next financial priority, the accumulation of emergency savings sufficient to cover three to six months of expenses. If the borrower’s income has continued and the emergency savings goal has been met, three options are available. First, continue to make the monthly student loan payment throughout the time period the provisions are in effect, with the full payment amount applying to principal since the interest rate is zero. Second, do not make the loan payments. Instead, invest the equivalent monthly student loan payment in a low-risk opportunity each month throughout the time period with plans to apply the investment proceeds to the loan balance when repayment obligations resume. Third, do not make the student loan payments but apply the equivalent monthly student loan payment to the repayment of other consumer debt such as credit card debt or an automobile loan.

The best advice for the borrower who has lost income is “don’t pay.” The equivalent monthly payment can be used to replace some of the lost income to cover basic living expenses. The best advice for the borrower who has not lost income but does not have an emergency savings fund is “don’t pay.” Accumulate the equivalent monthly payment to build this financial buffer. The purpose of this paper is to analyze the three options available to someone who has emergency savings and whose income was not interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Should the borrower continue to make the monthly student loan payments or not?

Options

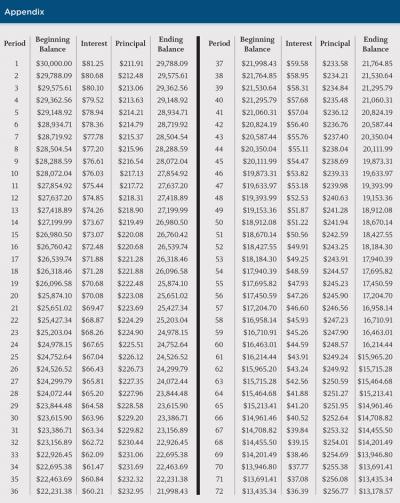

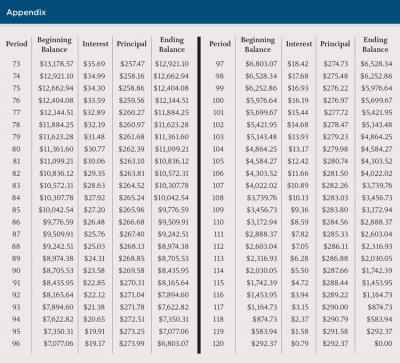

Assume a borrower owes $30,000 in student loans, a bit less than the average per borrower for 2020. Also assume the loan has a 10-year maturity and a 3.25 percent APR, with monthly payments of $293.16. The loan amortization over the 120-month life of the loan is provided in the Appendix.

Option 1: The borrower makes their monthly student loan payment throughout the 18-month period with the full payment applying to principal. The interest portions of the first 18 payments total $1,373.41, which would reduce the principal balance instead. The amount would cover the principal portion of payments for the next 8 to 9 months, shortening the overall life of the loan from 120 months to between 111 and 112 months. The benefit of this option is greatest in the first 18 months when the interest portion of each payment is highest. For the borrower in the last years of the loan’s maturity, the benefit is greatly reduced. For Payments 101 through 119, the total interest amounts to an additional $161.10 applied to the principal owed. The loan life is not shortened, but the final payment for month 120 is reduced from $293.16 to $131.63 ($131.27 principal plus $0.36 interest). For borrowers with student loans at a higher rate than 3.25 percent APR, the benefit is even greater. As the interest rate on the student loan increases, the reduction in loan maturity is also increased.

Option 2: Invest the equivalent monthly student loan payment amount in a low-risk, liquid opportunity and apply the investment balance to the student loan principal balance when the CARES Act provisions expire. A passbook savings account has the investment characteristics needed. The borrower will make monthly investments of $293.16, and the minimum deposit to open a passbook savings account with many banks is $100.00. It offers flexibility in the timing and amount of deposits. The investment is of low risk thanks to deposit insurance. Finally, it is liquid, which gives the investor the ability to withdraw funds whenever the student loan repayment schedule resumes. The national average passbook rate for banks and thrift institutions was 0.09 percent APY on October 21, 2020.3 The interest earned at this rate on the monthly payment for 18 months is $3.37. The borrower realizes the same interest savings as with Option 1 ($1,373.41), plus the additional interest is earned ($3.37) for a total of $1,376.78. The additional interest earned is also applied to the loan balance, which shortens the overall life of the loan slightly more than with Option 1. This alternative relies on the financial discipline of the borrower to invest rather than spend the funds.

Option 3: Redirect the equivalent monthly student loan payment to other debt such as credit card balances or auto loans. The average credit card rate for the week of March 17, 2021, was 16.12 percent. The average rate on a car loan ranged from 3.24 percent for borrowers with credit scores of 781–850 to 13.97 percent for borrowers with credit scores of 300–500.4 This alternative will require financial discipline on the part of the borrower.

Option 1 calls for continuation of monthly payments with the full payment amount reducing principal owed. This course of action benefits the borrower by shortening the overall maturity of the student loan debt. This results in a reduction in the overall life of the loan, but an even greater reduction will be achieved by following the second strategy.

Option 2 and Option 3 assume the borrower will not continue to make payments as scheduled. With Option 2, the borrower invests the equivalent monthly payment in a low-risk, liquid opportunity and takes advantage of both the interest savings of Option 1 plus additional interest earnings from investing. When the CARES Act provisions expire, the accumulated balance is applied to the student loan debt. Option 3 assumes the borrower has other debt in addition to eligible student loan debt and will use the equivalent student loan payment to pay down the other debt. Option 3 is better than Option 1 if the interest rate on the other debt is greater than the student loan interest rate. Option 3 is better than Option 2 if the interest rate on the other debt is greater than the sum of the student loan interest rate and the investment rate of return. Using the interest rates from this paper as examples, the benchmark would be 3.34 percent (3.25 percent student loan rate plus 0.09 percent passbook savings rate). If the borrower has credit card debt at a 16.12 percent rate, the borrower should redirect the monthly student loan payment funds to the more expensive credit card debt. But if the borrower has an auto loan at 3.24 percent and student loan debt at 3.25 percent, the best strategy of the three is Option 2, which yields a return of 3.34 percent.5

Conclusion

Sound financial management calls for borrowers to repay their loans as contractually scheduled; however, the CARES Act has eliminated the negative consequences for nonpayment of eligible student loans for an 18-month period. We conclude the best advice during this time period for all borrowers with eligible student loans is “don’t pay!”

If the borrower has lost income or employment during the pandemic, “don’t pay!” Instead, the equivalent funds should be used for high-priority needs such as housing, food, or medical expenses. If the borrower has not lost income or employment but does not have savings sufficient to cover three to six months of expenses, “don’t pay!” Instead, use the equivalent monthly student loan payment to build an emergency savings fund.

If the borrower with emergency savings did not suffer a loss of income during the 18-month period the CARES Act student loan provisions are in effect, “don’t pay!” Three options are examined. Option 1 calls for continuation of student loan monthly payments with the entire amount reducing principal owed. This results in a reduction of eight to nine months in the overall life of the loan, but an even greater reduction will be achieved by following the strategy described in Option 2. Instead of making the monthly payments, invest the equivalent monthly payment in a low-risk, liquid opportunity and take advantage of the interest savings of Option 1 and the additional interest earnings from investing. Borrowers can apply the balance accumulated to their student loan debt when the CARES Act provisions expire. The Option 3 strategy is considered when the borrower has other debt. Instead of making the monthly student loan payments, borrowers can apply the funds to pay down the other debt. It is the optimum approach when the interest expense on the other debt is greater than the interest savings plus interest earnings with Option 2. However, if the interest expense on other debt is less than interest savings plus interest earnings from the low-risk, safe investment, Option 2 is better than Option 3. The unique financial circumstances of the individual will determine whether Option 2 or Option 3 is the better alternative.

A final reason to favor the nonpayment Options 2 and 3 over payment Option 1 is the possibility of student loan forgiveness. Thus far, the Biden administration has targeted student loan cancellation for specific and unusual circumstances such as borrowers with disabilities, but there are calls for providing relief to a much larger percentage of student loan borrowers.

Endnotes

- See “Payroll employment down 20.5 million in April 2020,” 2020, May 12. The Economics Daily, U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/payroll-employment-down-20-point-5-million-in-april-2020.htm#.

- See “Monthly unemployment rate in the United States from February 2020 to February 2021 (seasonally adjusted),” Statista. www.statista.com/statistics/273909/seasonally-adjusted-monthly-unemployment-rate-in-the-us/.

- See “Passbook and statement savings rates,” 2020, October 21, Bankrate. www.bankrate.com/finance/savings/passbook-and-statement-savings-rates.aspx.

- See “Current Auto loan rates for 2021,” Bankrate. www.bankrate.com/loans/auto-loans/rates/.

- An Excel worksheet that can be customized for differing student loan and investment options is available by contacting the authors.

References

Foster, Sarah. 2020, July 9. “Survey: Nearly half of U.S. households have had incomes cut during coronavirus pandemic.” Bankrate. www.bankrate.com/surveys/coronavirus-and-income-reduction/.

Friedman, Zach. 2020, February 3. “Student Loan Debt Statistics In 2020: A Record $1.6 Trillion.” Forbes. www.forbes.com/sites/zackfriedman/2020/02/03/student-loan-debt-statistics/?sh=388d037281fe.