Journal of Financial Planning: December 2014

Jacob P. Sybrowsky, Ph.D., CRC, RFC, is an assistant professor and personal financial planning program director for the Woodbury School of Business at Utah Valley University. He also works with Evensky and Katz Wealth Management out of Coral Gables, Florida. Email author HERE.

Michael Finke, Ph.D., CFP®, is professor and director of retirement planning and living in the department of personal financial planning at Texas Tech University. He served as president of the American Council on Consumer Interests, is the past editor of the Journal of Personal Finance, and a contributing editor to Research Magazine. Email author HERE.

Hyrum Smith, Ph.D., CFP®, CPA, is an associate professor of personal financial planning at Utah Valley University. He formerly worked as an assistant professor at Virginia Tech in the personal financial planning program, a senior treasury analyst at SUPERVALU (formerly Albertsons), and an assurance associate at KPMG. Email author HERE.

Executive Summary

- Individual attributes, including propensity to trust, are established personality constructs related to choice under uncertainty.

- Trust is reliance on the integrity of a future payout or confidence in the certainty of future payment. As trust increases, individuals place greater weight on the probability of positive outcomes. The degree to which individuals and households allow these attributes to influence their decision-making, these characteristics will influence their portfolio choice.

- This study tests the relationship of trust and portfolio choice. Results show that those who are less trusting are less likely to select a portfolio with risky assets. By seeking to understand a client’s willingness to trust, in addition to risk tolerance levels, a financial planner can better customize a portfolio to meet a client’s needs.

Stock investment requires some understanding of the risk-return trade-off, as well as a certain trust that the data and analysis used to make risk reward assumptions is reliable (Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales 2005). Households must achieve a certain level of trust in the market system before they are willing to engage in stock market transactions. From an investment perspective, trust is a person’s reliance on the integrity of a future payout or confidence in the certainty of future payment. Trust consists of two key components: objective characteristics of the capital market system (regulation and enforcement), and subjective characteristics—this can include those who help facilitate the market system, such as financial planners.

Past research has shown that educational attainment is associated generally with the level of trust that an individual has in those making financial decisions on their behalf (Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales 2004). Thus, those with higher education levels may have greater confidence in future payouts and be more willing to invest in risky assets. Religion and other cultural factors are also associated with trust in a general sense, and that may impact willingness to invest in equities (Guiso et al. 2005). As a factor in decision-making, trust is unlikely to vary greatly over time, such that an initial incorrect preconceived notion developed in adolescence or the college years may persist over time and may influence investment decisions throughout the life cycle.

Prior research has focused on trust as a barrier to willingness to invest in the stock market (Haliassos and Bertaut 1995; Vissing-Jørgensen and Attanasio 2003). This study adds to the current body of literature by exploring trust, not as a factor in stock market participation, but as a factor associated with preferred portfolio composition.

Trust and Financial Transactions

Trust, within the domain of financial planning and as defined by Yamauchi and Templer (1982), is a lack of hesitancy, suspicion, or doubt regarding situations involving money. Others have noted that trust is composed of at least two different aspects.

Affective trust, or the trust that those on the opposite side of a financial transaction are intrinsically motivated (Rempel, Holmes, and Zanna 1985), has been shown to be positively associated with future transactions. Therefore, an individual with greater affective trust is more likely to believe that fund managers and financial planners have their best interests in mind. Because affective trust may be the result of exposure to a product or service (Edell and Burke 1987), the more affective trust an individual possesses (specifically regarding exposure to financial products), the more likely they may be to purchase a risky asset.

Cognitive trust, on the other hand, is the ability to rely on a service provider’s competence and reliability (Moorman, Zaltman, and Deshpande 1992). Cognitive trust is developed through prolonged exposure to or observation of agent financial behavior (Johnson and Grayson 2005). This trust may be developed through prolonged exposure to capital markets. An individual who has developed cognitive trust will be more likely to invest in a risky asset based on their unique understanding of the capital market system.

Furthermore, an individual who is generally trusting may be more willing to engage in financial transactions where a relationship of trust has not been established. Increased educational attainment may increase cognitive trust to some degree; however, cognitive trust is based on assurance of another individual’s competence level (Johnson and Grayson 2005). So where there is a basis for trust, some may feel increased optimism when engaging in financial transactions.

Lachance and Tang (2012) provided evidence that trust and cost are the two most important determinants of seeking financial advice, however they primarily focused on factors that lead to greater trust in financial advice. Instead, this study focuses on evaluating the relationship between trust and the specific preference toward investing in stocks or equities.

Theoretical Framework: Asset Demand Theory

An active line of financial economics research attempts to explain optimal portfolio allocation with risky assets (Maenhout 2004). Much of the current literature stems from seminal articles published by Merton (1969) and by Samuelson (1969). Under the assumptions of a frictionless market and the absence of labor income, portfolio share in equities was found to be consistent over the life cycle. These findings, and their underlying assumption, stand in stark contrast to recommendations made by financial planners who generally advise limiting equity exposure, especially when clients are faced with a short-run time horizon and for those in the latter stages of the life cycle. Relaxing the assumptions of a frictionless market and absence of labor income allows for the inclusion of additional factors that may impact portfolio allocation choice, such as the uncertainty about the return process (Maenhout 2004).

The issue of uncertainty regarding returns has been approached by other scholars. Heaton and Lucas (2000) found that return variation is a function of historical increases in stock market participation. Others have noted low dividend yields (Campbell 2000) and a lack of consensus on the risk premium (Cochrane 1998) increase uncertainty in the market. Based on the impact that uncertainty has in the market, Maenhout (2004) argued that it is necessary to consider how individuals may deal with uncertainty when making portfolio allocation decisions.

A key assumption when applying portfolio choice is that households worry about the possibility of a worst-case scenario. Where a household is more trusting, they are more likely to be optimistic and assign lower subjective probability to negative outcomes. Known as a Duffie-Epstein investor, this type of household optimistically deals with risk aversion (Kahneman and Tversky 1979), intertemporal substitution, and uncertainty aversion (Duffie and Epstein 1992). A more skeptical household is constrained by their preferences and applies greater strength to the possibility of a negative outcome, which may increase aversion to uncertainty. A more trusting household differs in preference by applying less strength to the possibility of a negative outcome (Maenhout 2004). Both households provide a framework for studying portfolio choice problems involving uncertainty (Anderson, Hansen, and Sargent 2003).

Decision-Making under Uncertainty

From a behavioral psychology perspective, decision-making requires a complex balance between cognitive abilities and emotional reaction. Where cognitive ability is limited, or information asymmetry exists, or emotion trumps rationality, the result may be a loss of utility (Brunnermeier and Parker 2004).

Household utility functions consist of two portions: utility from immediate consumption, and discounted expected utility from future consumption. Forward-thinking households have higher expected utility if they are optimistic. Households expect greater utility if they are optimistic and overestimate future market gains. However, this optimism or belief that one can control or impact future results affects daily decision-making and may result in realizing less of an investment gain than expected. This can result in decreased realized future utility. A simple belief in high future returns will not actually increase returns.

Modern asset pricing theory typically ignores assumptions about an agent’s beliefs (Epstein 1994). When uncertainty exists, individuals cannot estimate probabilities reliably and therefore, cannot accurately calculate expected values (Keynes 1936). Individuals prefer to act on known (objective) rather than unknown (subjective) probabilities (Epstein 1994). The hesitancy, suspicion, or doubtful nature of those who are less trusting decreases their subjective optimism, thus decreasing the likelihood of holding risky assets in a portfolio. Those who are highly optimistic are likely to overweight positive outcomes, and therefore, with greater optimism, may hold a greater share of portfolio wealth in equities.

Asset Pricing

The basic equation of asset pricing can be summarized as follows (Campbell 2000):

Pit = Et [Mt+1xi,t+1]

Where, Pit is the price of a risky asset, i at time, t (present). Et is the conditional expectations operator given current information today. Et is conditional on the perception of the operator or individual investor. xi,t+1 describes the random payoff on an asset i at time t+1 (one period in the future). Mt+1 is the stochastic discount factor. The use of xi,t+1 and Mt+1 imply that the investment return is both random or unknown and risky (subject to Mt+1 being positive). The model also generalizes the notion of a discount factor in a world of uncertainty. Where uncertainty does not exist, or if investors are risk neutral, the stochastic discount factor is constant and expected payoffs are converted to present values (Campbell 2000).

Of primary importance is the effect of Et on the price of a risky asset. Et is applied to xi, t+1 and Mt+1 . Where expectations are high—as is the case for those who are trusting—a positive Et will increase xi, t+1 and Mt+1 and the perceived price of an asset. Consider two investors with access to identical information. Assuming that Mt+1, the stochastic discount factor1, is equal to 0.75 and that xi t+1 , the random future payoff or price of a risky asset is $8, the price of the asset today would be $6 per share without considering the conditional expectation operator. If the market price of the asset is $6 per share today, the demand from both investors would be equal.

If, however, a more trusting investor A assigns a higher subjective probability to his expectations (Et = 0.60) and a less trusting investor B assigns a subjective probability to investment outcomes (Et = 0.40), the price that each would be willing to pay changes. Investor A would be willing to pay $3.60 (.60(0.75* $8)). Based on a market rate of $6 per share, and holding all else equal, demand for the risky asset would be higher, relative to investor B who would value the asset at $2.40 (0.40(0.75* $8)).

Therefore, if greater trust leads to more positive expectations, more trusting individuals should be willing to demand more risky assets, in general, and allocate more to risky assets in their portfolios. As such, the following hypothesis was tested in this study: households with higher levels of trust are more likely to prefer a higher percentage of stocks in their portfolios.

Methodology

Data and sample characteristics. The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79) was used as the primary data source for this study. Basic demographic information was collected in 1979. Financial, educational, marital, regional, time preference, and income-related data were collected in 2004. The trust variable was collected in 2008. These are the only years for which data were available. After introducing selection criteria and constraining the sample, the usable number of respondents was 4,500.

Empirical model. To test whether households with higher levels of trust are more likely to prefer a higher percentage of stocks in their portfolios, trust was included as a proxy for expectations in the following binary logistic empirical model:

log (Pi/1-Pi)= β0 + β1 Trust i + β2

Demographic controls i + β3 Educationcontrols i + β4 Income controls i + β5 Other controls i + ε i

In this paper, two logistic regression models are presented, each with the same independent variables but with a different binary dependent variable. In the first model, pi = the probability that household i owns stock (see results in Table 3). In the second model, pi = the probability that household i prefers at least 50 percent stock ownership in a portfolio (see results in Table 4).

Preferred Portfolio Composition Variables

Optimal percentage of equities held in a household portfolio was calculated using a single question in the 2004 reporting year of the NLSY79. Respondents were first asked the following question:

Suppose that you have to make the following choice: First, you could stay in the current Social Security program, where the government promises you a benefit based on your earnings. Or second, you could put part of your Social Security taxes (say 20 percent) into a personal retirement account where you decide how to invest that money. If you take this second choice, the Social Security benefit that you are currently promised will be reduced by 20 percent because you will be putting that part of your Social Security taxes into your personal retirement account. But at retirement, you will also get whatever money is in your personal account, which will depend on the investments you make. Which would you choose—to stay in the current Social Security program or to replace part of your Social Security with a personal retirement account? (NLSY79 R80464.00)

In the total sample, 2,308 respondents opted to stay in the current Social Security system, 5,014 respondents opted to place part of their Social Security contributions into a privatized account, and 243 respondents were either undecided or stated that it would depend on other factors.

Respondents were next asked to engage in a hypothetical decision assuming that they were required to invest a portion of the Social Security contributions in a privatized account. Interviewers stated that the respondent would be able to invest all or part of their contribution in one or more of the following types of accounts: stocks, bonds issued by private companies, or government bonds. Of those answering the question, 4,206 indicated that they would invest some portion of their Social Security funds in stocks.

Finally, interviewers asked: “What percentage of your personal retirement account money would you put into each type of investment?” (NLSY79 R80467.00

Respondents were allowed to estimate their optimal equity level and respond in 10 percent increments from 0 percent invested in stocks to 100 percent invested in stocks. For coding purposes, respondents who preferred to put 50 percent or more of their funds into stocks, private bonds, or government bonds were considered to have a preference for that particular asset class. As the dependent variable, this question provides a unique view of an individual’s optimal equity portion in portfolio construction based on a hypothetical scenario involving Social Security.

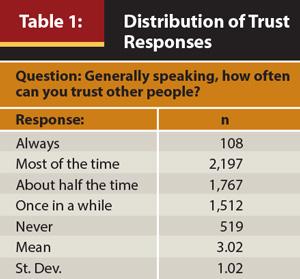

Trust. Trust was measured using a single question from the 2008 NLSY79 reporting year. Respondents were asked the following question: “Generally speaking, how often can you trust other people?” (NLSY79 T21845.00)

Respondents were able to answer using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from always to never. As shown in Table 1, responses were centered around the middle response with one standard deviation encompassing responses from “most of the time” to “once in a while.”

Demographic variables. Other studies have shown differences in race, gender, age, geographical region, and family structure. These variables were included to account for potential differences in portfolio preference. For the race variable, the comparison group was whites, the largest group in the sample. For gender, male was used as the comparison group. The age of survey respondents in the 2004 wave of the NLSY79 ranged from 39 to 47. Three age categories were created with the youngest third—those who were age 39 to 41—compared to those ages 42 to 44, and 45 to 47, respectively.

Guiso et al. (2005) hypothesized that regional factors are associated with variation in levels of trust. Region was included to control for any possible variance associated with household location. Dummy variables were created for geographic regions. The comparison group for region was those living in the western United States.

To control for differences based on family structure, marital status was included. Marital status was separated into three groups: single (those who had never been married), married, and divorced/separated/widowed.

Measurement issues. Demographic information from 1979 was combined with the control variables from 2004 and 2008. The dependent variable—optimal equity portion of the portfolio—was derived from 2004 data. Logistic regression was used to test the relationship between the dependent variables and explanatory variables.

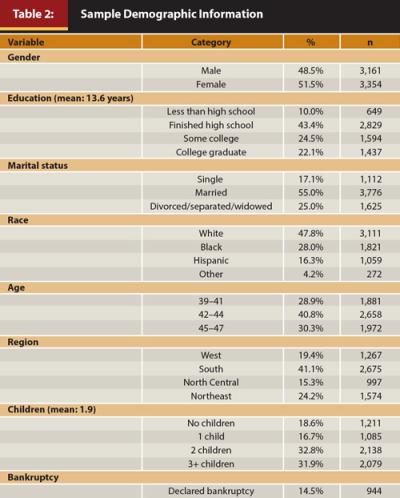

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics for the sample. The sample was slightly skewed toward male respondents (51.5 percent male to 48.5 percent female). For race, white respondents made up the largest group of the sample (47.8 percent). Respondents lived throughout the United States, with the highest concentration of respondents in the South (41.1 percent), with the balance of respondents living in the Northeast (24.2 percent), the West (19.4 percent), and North Central (15.3 percent) areas of the United States. Just over one-half of respondents were married in 2004 when most of the model’s variables were first recorded (55 percent). Twenty-five percent of respondents were divorced, separated, or widowed in 2004.

The mean education level of respondents was 13.6 years. The majority of respondents had graduated from high school or begun college in 2004 (43.4 percent and 24.5 percent, respectively). Few (10 percent) never finished high school. The remaining respondents finished college or attended graduate school (22.1 percent). The number of children in a household ranged from none to 11 or more. The mean number of children per household was 1.9, consistent with the national average, per 2009 U.S. Census Bureau data. More than 14 percent of respondents had declared bankruptcy.

Results

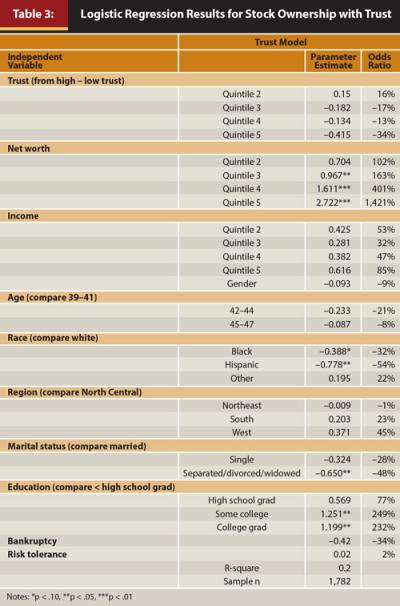

Table 3 reports logistic regression analysis results for trust as a factor of actual equity ownership. The table provides a baseline measurement for logistic regressions reported later.

In this model, trust was not significantly associated with actual stock ownership. Net worth was the strongest factor associated with actual equity ownership. In the model, there was a monotonic relationship between quintiles of net worth and equity ownership. Individuals in the third quintile were 163 percent more likely to own stocks than those in the first quintile. The fourth and fifth quintiles were 401 percent and 1,421 percent more likely to own stock, respectively.

Education level was the next strongest factor associated with stock ownership. Compared to those who did not graduate from high school, individuals who graduated from high school and attended at least some college were 249 percent more likely to own stocks. Results were similar for those who graduated from college or graduated from college and attended graduate school. They were 232 percent more likely to own stock.

Race and marital status were also significant factors related to stock ownership. Blacks were 32 percent less likely to own stocks compared to whites. Hispanics were 54 percent less likely to own stocks. Also, compared to married individuals, those who were separated, divorced, or widowed were 48 percent less likely to own stocks. The model explained about 7 percent of the variance in actual stock ownership.

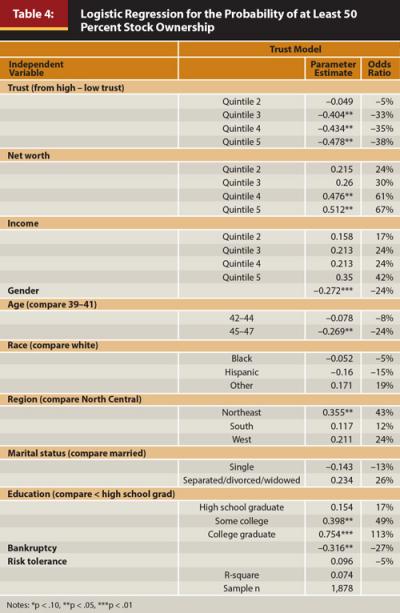

Table 4 shows logistic regression results for those who preferred at least 50 percent stock ownership in a hypothetical portfolio.

Table 4 shows that trust is significantly associated with a preference for at least 50 percent stock allocation. Individuals who are least trusting of others were 38 percent less likely to prefer a portfolio composition of 50 percent or more in stocks. The relationship was monotonic as the fourth and third quintiles were 35 percent less and 33 percent less likely to prefer a predominantly equity portfolio, respectively.

As with the previous model, net worth was also a strong factor associated with preferring at least 50 percent allocated to equities. In the model, the relationship between net worth and majority equity ownership was monotonic, with those in the highest two quintiles being 67 percent more likely (fifth quintile) and 61 percent more likely (fourth quintile) to prefer a portfolio composed of 50 percent or more in stocks, respectively. Income was not a significant factor in this model.

Education level was the next strongest factor related to majority stock ownership. Compared to those who did not graduate from high school, individuals who graduated from high school or attended at least some college were 49 percent more likely to prefer a high equity portfolio. Those who graduated from college or graduated from college and attended graduate school were 113 percent more likely to prefer stock ownership.

Gender was significantly associated with a preference for at least 50 percent allocation toward equities. Women were 24 percent less likely than men to prefer a portfolio with 50 percent or more invested in equities. Age was significant in that those who were in the highest age category (age 45–47) were 24 percent less likely to prefer a high equity portfolio compared to those in the lowest age category (age 39–41). We also see a regional effect, in that those in the Northeast were 43 percent more likely to prefer a high equity portfolio, compared with those living in the North Central region of United States. Finally, bankruptcy was a significant factor related to a stronger preference for equity allocation within a portfolio. Those who had declared bankruptcy were 27 percent less likely to prefer a high equity portfolio.

Discussion

This study tests the role trust plays in shaping portfolio composition. Net worth and education were shown to be most positively associated with preferring at least 50 percent stock ownership in a portfolio, however those with greater levels of trust also preferred at least 50 percent stock allocation in a portfolio. Results followed the theoretically predicted path and confirmed the hypothesis: households with higher levels of trust were shown to be more likely to prefer a higher percentage of stocks in their portfolios.

Those who are least trusting were 38 percent less likely to prefer a portfolio composition of 50 percent or more in stocks compared to the most trusting respondents. Those in the fourth and third quintiles followed a monotonic path, as they were 35 percent less and 33 percent less likely to prefer a predominantly equity portfolio, respectively.

Net worth was the strongest factor associated with preference for stock ownership. Those in the highest quintile of net worth were 1,421 percent more likely to hold stock compared to the lowest quintile (see Table 3). Those in the highest two groups of net worth were 67 percent more likely and 61 percent more likely to prefer a portfolio comprised primarily of equities, respectively (see Table 4).

Education was also a strong factor associated with preference for stock ownership. Generally, higher levels of education were associated with a higher likelihood of actually owning stocks and greater preference toward an equity-based portfolio. This preference is likely due to greater human capital, financial sophistication, and higher net worth, which provide more resources for monitoring costs (Ehrlich, Hamlen, and Yin 2008; Perraudin and Sorensen 2000).

Those who had declared bankruptcy were less likely to prefer a stock-based portfolio. An aversion to stocks may stem from bankruptcy proceedings, where stocks may have been seized to pay debts. If that is the case, a lower preference for stocks may be a precautionary measure against the possibility of future loss through bankruptcy. Aversion to equities may be an unintended negative consequence of bankruptcy, especially considering that assets held in retirement plans are generally exempt from seizure in bankruptcy proceedings.

Implications for Financial Planners

Financial planners face the difficult task of helping individuals and households manage finances today as well as in the future. Personal characteristics including trust, as well as education, gender, region, and race influence the likelihood that an individual will prefer equities. Knowledge of these preferences may help financial planners understand their clients in a new way. Additional information may lead to more specific advice and a greater ability to serve clients’ needs.

Specifically, financial planners may note that the degree to which many individuals trust others may impact their preference toward stocks, or at least a portfolio that is largely comprised of stocks. The threshold of trust (compared to those who “always” trust others) is trusting about half of the time to never trusting. If a planner believes that a primarily stock portfolio is in the best interest of the client, greater care should be taken to balance the desires of the client with their portfolio needs. Through integrating trust-related questions in risk tolerance questionnaires, separate personality tests, or interviewing and listening to their clients, financial planners may better gauge the trust level of their clients and make more appropriate portfolio recommendations.

Individuals with higher education were found to be more likely to select a majority stock portfolio. Given the benefits of diversification using assets that are less than perfectly positively correlated, some with higher education levels may be better served with a more balanced portfolio. Although based on life cycle stage, a preferred portfolio of greater than or equal to 50 percent stocks is not necessarily inappropriate for the sample used in this study. Human capital, specifically investment knowledge, may mitigate potential loss of returns for those who opt into a more risky portfolio. The same may be true for individuals who are highly risk tolerant.

Results from this study suggest that trust may generally explain willingness to engage in any risky activity (although additional research is necessary to confirm a potential link). Development of trust is vital in any agent-client relationship, especially where credence goods, such as financial planning advice, are involved. Ultimately, a financial planner may use these findings to better understand some of the personal characteristics that shape individual investment preference. By doing so, a financial planner may better meet client needs and increase the effectiveness of planning advice.

Endnote

- A stochastic discount factor comes from the fact that the present value or current price of an asset can be modeled by discounting a future payoff or cash flow, Xi t+1, by a stochastic or random factor, Mt+1, and then taking the expectation of this discounted payoff.

References

Anderson, Evan W., Lars Peter Hansen, and Thomas J. Sargent. 2003. “A Quartet of Semigroups for Model Specification, Robustness, Prices of Risk, and Model Detection.” Journal of the European Economic Association 1 (1): 68–123.

Brunnermeier, Markus K., and Jonathan A. Parker. 2004. “Optimal Expectations.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 10707.

Campbell, John Y. 2000. “Asset Pricing at the Millennium.” The Journal of Finance 55 (4): 1515–1567.

Cochrane, John H. 1998. “Where Is the Market Going? Uncertain Facts and Novel Theories.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w6207.

Duffie, Darrell, and Larry G. Epstein. 1992. “Asset Pricing with Stochastic Differential Utility.” Review of Financial Studies 5 (3): 411–436.

Edell, Julie A., and Marian Chapman Burke. 1987. “The Power of Feelings in Understanding Advertising Effects.” The Journal of Consumer Research 14 (3): 421–433.

Ehrlich, Isaac, William A. Hamlen Jr, and Yong Yin. 2008. “Asset Management, Human Capital, and the Market for Risky Assets.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w14340.

Epstein, Seymour. 1994. “Integration of the Cognitive and the Psychodynamic Unconscious.” American Psychologist 49 (8): 709–724.

Guiso, Luigi, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales. 2004. “Cultural Biases in Economic Exchange.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w11005 (subsequently published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics).

Guiso, Luigi, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales. 2005. “Trusting the Stock Market.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w11648.

Haliassos, Michael, and Carol C. Bertaut. 1995. “Why Do So Few Hold Stocks?” The Economic Journal 105 (9): 1110–1129.

Heaton, John, and Deborah Lucas. 2000. “Stock Prices and Fundamentals.” In NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1999, Volume 14, 213–264. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Johnson, Devon, and Kent Grayson. 2005. “Cognitive and Affective Trust in Service Relationships.” Journal of Business Research 58 (4): 500–507.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. “Prospect Theory.” Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 47 (2): 263–291.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. London: Macmillan.

Lachance, Marie-Eve, and Ning Tang. 2012. “Financial Advice and Trust.” Financial Services Review 21 (3): 209–226.

Lucas Jr, Robert E. 1978. “Asset Prices in an Exchange Economy.” Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 46 (6): 1429–1445.

Maenhout, Pascal J. 2004. “Robust Portfolio Rules and Asset Pricing.” Review of Financial Studies 17 (4): 951–983.

Merton, Robert C. 1969. “Lifetime Portfolio Selection under Uncertainty: The Continuous-Time Case.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 51 (3): 247–257.

Moorman, Christine, Gerald, Zaltman, and Rohit Deshpande. 1992. “Relationships between Providers and Users of Market Research: The Dynamics of Trust within and between Organizations.” Journal of Marketing Research 29(3): 314–328.

Perraudin, William R.M., and Bent E. Sorensen. 2000. “The Demand for Risky Assets: Sample Selection and Household Portfolios.” Journal of Econometrics 97 (1): 117–144.

Rempel, John K., John G. Holmes, and Mark P. Zanna. 1985. “Trust in Close Relationships.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49 (1): 95–112.

Samuelson, Paul A. 1969. “Lifetime Portfolio Selection by Dynamic Stochastic Programming.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 51 (3): 239–246.

Vissing-Jørgensen, Annette, and Orazio P. Attanasio. 2003. “Stock-Market Participation, Intertemporal Substitution, and Risk-Aversion.” The American Economic Review 93 (2): 383–391.

Yamauchi, Kent T., and Donald J. Templer. 1982. “The Development of a Money Attitude Scale.” Journal of Personality Assessment 46 (5): 522–528.

Citation

Sybrowsky, Jacob, Michael Finke, and Hyrum Smith. 2014. “Trust: A Factor in Portfolio Composition.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (12) 54–61.