Journal of Financial Planning: February 2014

Mistakes are inevitable in any field of human services. By “mistake” we mean an unintentional event that may have meaningful adverse consequences for the financial adviser and/or the client. Account transfer errors, an adviser’s failure to implement a planned tax or insurance action, or investment trading errors that result in a client suffering financial loss are some examples.

Such errors may have consequences for the client, the employee who made the mistake, and you, if you are responsible for supervising that employee or overseeing the company. A very serious mistake may even threaten the survival of an entire firm.

Making a mistake generally doesn’t arise from unethical behavior. Carelessness, miscommunication, or a misunderstanding more often lies at the heart of the matter. However, denying or covering up a mistake made by you or someone else in your firm is unethical behavior, especially if the mistake causes harm to someone else.

The questions advisers must address in the aftermath of a mistake are central to the advising relationship: How will you deal with the consequences of mistakes impacting clients? Will you wait to figure out your response in the spur of the moment under pressure, or will you take time now to train yourself and your staff so they will be prepared when the need arises?

There are ways to be proactive, ethical, empathic, and responsive in the aftermath of a mistake, to deliver what we consider “a proper apology.” The methodology described in this article can help you:

- repair the mistake and any breach it may cause in the client relationship

- improve your chances of retaining the client relationship

- create an opportunity to strengthen the client relationship

- minimize the risk of a mistake escalating into a much more serious problem later

- teach and reinforce the highest level of values, attitudes, and behaviors within your firm

- strengthen your relationship with the staff member who made the mistake, assuming you wish to retain the services of that employee

- prevent future mistakes

Learning from the Health Care Profession

A growing body of knowledge exists about effective client-centered error resolution based on initiatives in the health care profession. Research has shown that how physicians, health care staff, and medical institutions handle errors in patient care strongly influences the outcome of attempts to repair the situation. Traditionally, mistakes were hidden as long as possible. Institutions stonewalled disclosure of details or possible resolutions, and everything was scrutinized through the lens of managing the risks and costs of potential litigation. This left patients and doctors with few options and damaged relationships. In the following examples of research from the health care profession, note the elements relevant to financial planning and wealth management:

Whether a patient (or client) seeks legal advice depends on the type of error, the severity of the outcome, and the level of disclosure (Manser 2005). In fact, the patient’s frustration with the professional’s failure to provide adequate disclosure following an error may have a significant influence on subsequent decisions to litigate the error (Singh 2010).

Several studies have found that a substantial portion of families who sued did so because they suspected a cover up or they felt no one would tell them what happened (Singh 2010). Thus, nearly half of the patients’ families who filed lawsuits did so out of the need for more information (Singh 2010, Hosansky 2002).

A system that values the internal disclosure of errors and their resolution in organizations is helpful to professionals. When people know what is going on in their system and the potential errors that might occur, they are more confident they can handle errors, because they know others have handled similar errors. Without open communication and adequate debriefing after an adverse event, feelings of incompetence, isolation, and psychological distress occur. These feelings may then lead to deterioration in work performance and a heightened risk of making more errors (Gallo 2010, Delbanco and Bell 2007, Fryer-Edwards 2004, Jackson 2004).

Beyond the health care profession, the Disney organization has extensively studied mistakes and customer service, concluding that “… the way Disney cast members rectify a disappointing service experience can have a more positive effect on customer loyalty than if the service is flawless” (Jones 2013).

Be Honest, Listen, and Communicate

To maintain trust in a relationship, you must maintain honesty, especially when it is most difficult for you to do so. When a mistake occurs that results in any degree of harm, clients want an apology that is sincere and effective. They want you to listen to their feedback about the impact of your mistake on their lives and on their relationship with you. They want you to respond in a manner that indicates that you have truly heard them.

Clients want to talk about the mistake for several reasons. First, they want to understand what happened. This does not mean they need to know the technical details—many of which may not be relevant—and providing too much detail can interfere with providing clarity about what happened. Excessively long explanations may overwhelm the client and can backfire by appearing to drown them in what you care about rather than what they care about. But do provide enough detail to allow the client to understand what happened. It must be a dialogue rather than a monologue. Answer their questions fully and openly.

Second, clients are watching and listening to you during your explanation to see if you are holding something back. Do not deny or deflect responsibility for what has happened when you genuinely have made an error. Show clients that you understand the big picture and that you are focused on their hurt, not yours.

Third, clients want to know what you will do to repair the damage. In hearing the explanation, clients begin to make decisions about whether the mistake was understandable, preventable, egregious, willful, or simply unfortunate. They want to hear your ideas about possible reparations, financial or otherwise. They want to judge whether your proposals seem fair, a key metric by which they will judge your trustworthiness for any future relationship.

Finally, clients want to see that you have fully researched what happened so you can prevent it from happening again to them or to others. A good investigation on your part reassures clients that, as a result of what happened, protections are now in place to prevent the mistake from happening again.

Handling aggrieved clients is one of the hardest tasks you have to perform as an adviser. You must keep your own emotions in check, a very difficult thing to do when under attack and afraid of potential consequences. Your natural tendency will be to defend yourself. You must not do that at this stage. Your client is very likely to interpret any defensiveness as indications that you are not accepting responsibility and are not focusing on the impact of the mistake on them.

Two Paths to a Proper Apology

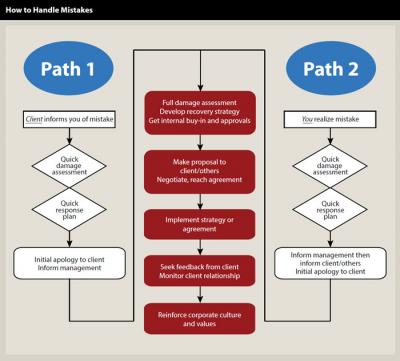

The flow chart shows two paths you can take to a proper apology, depending on how you first become aware a mistake has occurred. In Path 1, you learn of the mistake from the client. In Path 2, you or a staff member discover the mistake before the client becomes aware of it. After the steps in the initial response, the two paths converge in a common pathway of resolution.

Most advisers will find Path 1 more challenging than Path 2. When you initially hear of the mistake from the affected client, you must have skills for responding appropriately without much time to reflect, investigate, or consult with others. You also are likely to be confronted with a very upset client, which is bound to escalate your anxiety. And when the client is angry or upset, you are more likely to react defensively. While understandable, reacting defensively exacerbates the situation, because the client senses you have become defensive, resulting in escalating emotions by both parties. Effective communication is impossible under these conditions, and no problem-solving work can be done.

It requires great skill not to argue or become defensive. Even if you think the problem may not be your fault, your best strategy is to listen and receive as completely as possible. Your goal is to understand. Trying to defend at this initial stage risks having your client respond with one or more of the following reactions: “You are not listening to me.” “If you can’t or won’t admit a mistake, how much can I trust you?” or “You are covering up something.”

The solution is for the adviser to keep his or her emotions in check, engage in active listening, and employ good interviewing techniques using open-ended questions and clarifying questions (Jaffe and Grubman 2011). If the adviser does this well and maintains a calm emotional state, within a few minutes the client’s emotional level should drop to match the adviser’s level, at which point a problem-solving discussion can occur. We recommend keeping the problem-solving discussion as brief as possible at this stage. The focus should be on agreeing the adviser will research the mistake and report back to the client within an agreed-upon timeframe, usually within no more than 24 hours.

In Path 2, the adviser learns of the mistake before the client. The clock is now ticking on informing the client. There is a window of opportunity of unknown duration to inform the client before the client discovers the mistake. By being the one to disclose what has happened, not only will you have the most control over the situation, you will appear the most trustworthy and you and your staff avoid the stress of living in limbo, wondering if and when the client will find out. And remember, you have an obligation to promptly inform the client that a mistake has occurred based on your responsibilities as an adviser.

- In preparing to inform the client of the mistake, complete these four steps within no more than a few hours of discovering the mistake, whenever possible:

- Inform management, or, if you are the manager, relevant organizational staff.

- Conduct a brief investigation to determine what went wrong.

- Estimate what may be required to remedy the situation.

- Formulate your initial response to the client.

In both Path 1 and 2, the common steps in the initial client discussion are to talk objectively about what has occurred (whether you are hearing about it or telling about it), take as long as necessary to listen to the client’s reactions without defensiveness or premature problem-solving, issue a sincere apology, and (when the client is calm and ready) do some initial problem-solving. Obtain a clear understanding of what the client considers to be a satisfactory resolution to the problem, not just what you think must be done. Although this may get fine-tuned as the resolution process occurs, you must find out what the client thinks is important so you can target that in your response plan.

You should take detailed notes of all discussions. This is not just for risk management; the notes will be helpful later when it is time to extract important lessons from the experience and to insure every aspect of the proposed solution is implemented as promised. Depending on the severity of the mistake, your initial response plan may be to simply answer the client’s immediate questions about what went wrong and to describe what you intend to do to formulate a full response. For example, it may be necessary for you to seek the assistance of the client’s tax attorney, CPA, or other advisers to resolve an issue, and that may take several days. Your initial response should help set the client’s expectations about how long a complete resolution may take. Be cautious when setting the client’s expectations. Make sure your actual performance exceeds whatever expectations you set.

A rapid response to resolve a mistake helps minimize damages and costs of restitution. However, “rapid” should not be interpreted as hasty. In many cases, it may be best to allow some time to elapse before completing the steps that appear in the center of flow chart. The optimal amount of time is usually one or two days.

Communicating Your Response Plan

All communications with the client should be tested against these standards to make sure they measure up:

- Tell the truth.

- Apologize, but how often? A good guideline is to apologize three times: once when the error is revealed, again at the end of the first conversation, and once at the beginning of the second call or meeting as you engage in the resolution process. Over-apologizing is as off-putting to a client as failure to apologize.

- Be empathetic, especially if the mistake has caused harm or inconvenience.

- Communicate enough detail about the situation so that the client can understand what happened and how.

- Explain what you are going to do to prevent a similar mistake in the future, such as changes in procedures or building in new fail-safes to your office protocols.

- Explain the proposed solution and timetable, and determine whether the solution is acceptable to the client.

- If the client has different views about solutions, negotiate with the client to reach a satisfactory resolution.

- Establish a follow-up plan to confirm that the situation has been resolved.

We strongly encourage role-playing the client communication elements in these steps to a proper apology. Role-playing allows you to rehearse, experiment, and learn how to handle a particular communication challenge.

Finally, monitor the client relationship closely over the next six to 12 months to see if trust appears to be intact, strengthened, or still fragile. Check in with the client to see if anything further needs to be discussed about how the error was handled.

What about Legal Advice?

If the problem is very serious, you may need to seek legal advice and notify your errors and omissions insurance carrier. Be aware that much of the advice contained in this article may be at odds with the advice of your insurance carrier or attorney. An insurance carrier’s objective is to minimize the potential financial loss that it may suffer in the event of a claim. Many attorneys still advise their clients to admit nothing and stonewall. Your insurance carrier also may try to insist that all communications be handled by attorneys, but that strategy may increase the risk of litigation.

What Is Appropriate for Your Firm?

Each firm has its own culture and values related to ethical performance, shared learning, and transparency. To determine how your firm will handle mistakes, you must first decide what your goals are regarding these. Here are some suggested goals for consideration:

- Create a culture that supports and reinforces telling the truth at all times. This includes supporting employees who promptly acknowledge mistakes.

- If sanctions are necessary, apply them fairly. Communicate clearly and openly about how mistakes are handled and how sanctions are applied.

- Create a learning culture that helps employees learn how to prevent mistakes.

The question of sanctions is a challenging one. An employee should be held accountable for making a mistake that negatively impacts a client, but what form of accountability is appropriate and constructive? Should employees be sanctioned for making mistakes? Is your system of sanctions consistent with encouraging employees to behave with integrity and openness? Remember, mistakes are inevitable in any highly complex human endeavor such as financial planning and wealth management. How mistakes are handled is one of the factors that distinguishes a good organization from a great one.

We have found that an initial positive approach may be to challenge the responsible employee to extract lessons from the experience that the employee can share with his or her colleagues, and then put the employee in charge of organizing a training session based on the experience. The goal of the training session is to turn one person’s negative experience into a learning opportunity for all. This will help the entire organization improve its performance, reinforcing the values of integrity, openness, and learning. Rarely, it may be necessary to terminate an employee who has made a mistake, particularly if the employee has been responsible for more than one significant error.

Conclusion

Mistakes that impact clients are inevitable. Handling these mistakes must take into account repairing the client’s trust of the firm and the adviser, along with the error itself. Financial firms should have protocols that hold employees accountable in a determined yet supportive manner and enable the firm to act with transparency, honesty, and rapidity to repair and reinforce the client relationship. Responding in this manner is consistent with the firm’s fiduciary duty to its clients and with truly effective client service.

References

Delbanco, Tom, and Sigall K. Bell. 2007. “Guilty, Afraid, and Alone—Struggling with Medical Error.” The New England Journal of Medicine 357 (17): 1682–1683.

Fryer-Edwards, Kelly. 2004. “Talking About Harmful Medical Errors with Patients.” University of Washington School of Medicine’s Tough Talk: Helping Doctors Approach Difficult Conversations.

Gallo, Amy. 2010. “You’ve Made a Mistake. Now What?” Harvard Business Review’s Blog. blogs.hbr.org/2010/04/youve-made-a-mistake-now-what.

Hosansky, Tamar. 2002. “Error Prevention, The Communication Factor.” MeetingsNet. meetingsnet.com/medical-meetings/error-prevention-communication-factor.

Jackson, Douglas W. 2004. “Dealing Honestly with Medical Errors: Should We Say We Are Sorry?” Orthopedics Today. November.

Jaffe, Dennis T., and James Grubman. 2011. “Core Techniques for Effective Client Interviewing and Communication.” Journal of Financial Planning’s Between the Issues. www.FPAnet.org/Journal/BetweentheIssues/LastMonth/Articles/CoreTechniques.

Jones, Bruce. 2013. “Lessons from Disney: Correcting Mistakes to Ensure Customer Loyalty.” Disney Institute. www.trainingindustry.com/media/3998204/disneycustomerloyaltyqualityservicelessons.pdf.

Manser, Tanja, and S. Staender. 2005. “Aftermath of an Adverse Event: Supporting Health Care Professionals to Meet Patient Expectations Through Open Disclosure.” Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 49 (6): 728–734.

Singh, Ranjit. 2010. “Dealing with Medical Errors: What Should I Say?” Department of Family Medicine, University of Buffalo Patient Safety Research Center. fammed.buffalo.edu/safety/files/5_Disclosure.pdf.

Roy C. Ballentine, CFP® ChFC®, CLU®, is founder and CEO of Ballentine Partners LLC (www.BallentinePartners.com), a wealth management firm with its principal office in Waltham, Massachusetts.

James Grubman, Ph.D., (www.JamesGrubman.com) is a psychologist and consultant to families of wealth and their advisers. He is the author of Strangers in Paradise: How Families Adapt to Wealth across Generations.