Journal of Financial Planning: February 2014

As the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) continues to examine the possible implementation of a uniform fiduciary standard, investment professionals who operate under suitability guidelines may be wondering how changing to a fiduciary model may impact their business and their client relationships. In an attempt to answer that question—as well as questions about differences in the advice and products registered representatives and investment advisers offer—we surveyed a national sample of nearly 400 investment professionals.

The results of that survey shed new light on the potential benefits to consumers of a uniform fiduciary standard and highlight the perceived impacts of changing one’s standard of care. This article will focus on those perceived impacts and a few of the potential consumer benefits, as well as provide an overview of the current and proposed regulatory landscape.

Current Regulatory Standards

Investment professionals designated as investment advisers must make recommendations that are in the client’s best interest, as they are required to follow a fiduciary standard. Investment professionals designated as registered representatives must make recommendations that follow a suitability standard; they are not required to make recommendations that are in the client’s best interest (under federal law), but their recommendations must be suitable given the clients’ investment objectives and financial situation.

Section 202(a)(11) of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (Advisers Act) defines an “investment adviser” as:

Any person who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others, either directly or through publications or writings, as to the value of securities or as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities, or who, for compensation as part of a regular business, issues or promulgates analyses or reports concerning securities.

Advice provided by registered representatives is considered incidental to the sale of financial products, whereas advice provided by investment advisers is considered central to their overall services. However, the 2008 RAND technical report Investor and Industry Perspectives on Investment Advisers and Broker-Dealers showed that consumers typically are unable to differentiate between a registered representative and an investment adviser. The RAND report also showed that adding to the confusion is the common practice for broker-dealers to promote and refer to registered representatives as financial advisers, wealth advisers, or financial consultants, implicitly stating that their services include specialized advice.

Fiduciary responsibility has been defined as the minimum obligation that professionals should have toward their clients; it is believed to be part of the contract of engagement between two parties (Laby 2008). The common types of professional relationships for which fiduciary standards may exist include principal-agent, trustee-beneficiary, and director-corporation relationships (Flannigan 2004). The client-investment professional relationship falls under the broader category of principal-agent relationships. Within the framework of a principal-agent relationship, the decisions and actions suggested or taken by the investment professional (the agent) can have long-term consequences for the financial outcomes and decisions of the client. (See “The Fiduciary Obligations of Financial Advisers under the Law of Agency” on page 42 of this issue of the Journal for more on the principal-agent relationship.)

Section 202(a)(11)(C) of the Advisers Act excludes from the definition of an investment adviser any broker or dealer that meets the following requirements: (1) the performance of investment advisory services is solely incidental to the conduct of its business as a broker-dealer, and (2) no “special compensation” is received for advisory services and the broker-dealer does not receive any additional compensation to provide such service to their customers. Thus, income earned by registered representatives often is through commissions from the products they sell.

Currently, there are substantially more registered representatives than investment advisers. Within the confines of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and FINRA guidelines, registered representatives are allowed to sell financial products but are not required to have any fiduciary responsibility in advising their clients. They are required to follow the FINRA suitability rule.

According to FINRA Rule 2111 effective July 2012, registered representatives must fulfill three main obligations.

First, a registered representative must have a “reasonable basis to believe, based on reasonable due diligence, that the recommendation is suitable for at least some investors.” Second, the products that a registered representative sells to a client must be suitable to that particular client’s investment profile. The third obligation applies when the representative has control over the client’s portfolio. This obligation imposes an overall suitability determination to a series of transactions, even if each transaction in isolation would be suitable. This obligation takes into account the asset turnover rates, cost to equity ratios, and in-and-out trading from a client’s account.

Proposed Uniform Fiduciary Standard

Section 913 of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) required the SEC to examine the potential effects of a uniform fiduciary standard for all investment professionals when they give investment advice to retail investors. Dodd-Frank also authorized the SEC to adopt regulations imposing the same fiduciary duty on brokers—and their representatives—that apply to investment advisers.

In 2011, SEC staff published the Study on Investment Advisers and Broker-Dealers, a lengthy report examining the effectiveness of standards of care. The report concluded by recommending to the SEC the imposition of a uniform fiduciary standard for investment advisers and registered representatives when they offer investment advice about securities to retail investors. The recommendation to the SEC was that the standard be consistent with the one that currently applies to investment advisers.

The survey findings reported in this article are the result of research that was designed, in large part, to determine whether some concerns about the merits of a uniform fiduciary standard are well grounded. The specific research questions addressed include (among others not reported in this article):

- Do registered representatives who currently follow a suitability standard perceive that a uniform fiduciary standard would impact them?

- Do investment advisers and registered representatives recommend the same investment products to their clients?

- Do investment advisers and registered representatives spend the same amount of time with their clients before they make investment recommendations?

The Survey

A 2012 online survey was used to collect primary data for this research study. The survey was designed and administered by faculty in the University of Georgia Department of Financial Planning, Housing and Consumer Economics in cooperation with Matthew Greenwald & Associates, a market research firm. The study sample consisted of 387 investment professionals from 48 states who currently “provide personalized investment advice to individuals or families as part of [their] job.”

Twenty percent of the 387 participants were registered as both an investment adviser (SEC) and as a registered representative (FINRA). These individuals were excluded from the analysis due to the ambiguity associated with following two different standards of care depending on how they work with clients. Thus, responses from 309 participants were examined for this research, including 134 registered representatives and 175 investment advisers. As a result of the constraints faced in reaching out to every financial planner in the country and time and costs associated with it, the sampling methodology used in this study was a convenience random sample.

Results

Would investment professionals who currently follow the suitability standard advise their clients differently if they were to follow the fiduciary standard instead?

Although all respondents were asked this question, the focus here is on the registered representatives who indicated they follow the suitability standard. Sixty-seven percent of that group did not expect their advice to be different under a fiduciary standard. However, 16 percent of registered representatives expected that their advice might be different if they were to operate under the fiduciary standard and 17 percent didn’t know. This result confirms that in the current situation, in which there are two different standards of care, at least some consumers may in fact receive different recommendations from investment professionals who follow different standards.

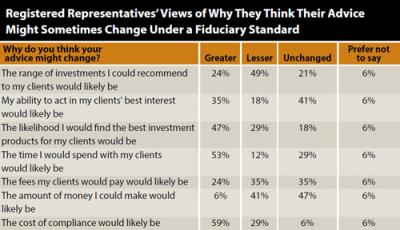

The 16 percent of registered representatives who reported they thought their investment advice might change under a uniform fiduciary standard were asked the follow-up question: “Why do you think your investment advice might sometimes be different when following a fiduciary standard?”

As shown in the table, 35 percent of the registered representatives who responded to this question expected their ability to act in the client’s best interest would be greater under a fiduciary standard. Nearly one-half (45 percent) thought they would have the same or a greater range of investment products to recommend to clients, and 49 percent thought there would be a smaller range of products available. The majority (53 percent) thought that under a uniform fiduciary standard they would likely spend more time with their clients.

All survey respondents—both investment advisers and registered representatives—also were asked about the investment vehicles/assets they recommend to clients. They were then asked to estimate the percentage breakdown between actively and passively (index) managed mutual funds they recommend. The results show some clear differences between the two types of investment professionals.

Significantly more registered representatives (83 percent) than investment advisers (43 percent) reported that they recommend a larger percentage of actively managed mutual funds than passively managed funds (t=8.044, p<.001). This further supports the conclusion that consumers may receive different guidance from investment professionals following different standards of care.

To determine any differences in the amount of time investment advisers and registered representatives spend with clients before making investment recommendations, survey participants were asked: “When working with a new client, on average, how many meetings either in-person, over the phone, or interactive online (such as using Skype but excluding email exchanges), do you have with your clients before making specific investment recommendations?”

Most investment advisers (86 percent) reported meeting with new clients an average of two or more times before recommending an investment, compared with 35 percent of registered representatives (t=3.052; p<.001). The bar graph illustrates the additional finding that 55 percent of registered representatives said they met with new clients only once, on average, before making an investment recommendation. It is quite alarming that 10 registered representatives and one investment adviser said they did not have a single meeting with a new client before making an investment recommendation.

Although the sample size here is relatively small, the results indicate potentially positive outcomes for clients of these registered representatives if their investment professional were subject to a fiduciary standard. The results also provide evidence (although from a very small subsample from the total sample) to suggest that registered representatives tend to believe that the cost of compliance would likely be higher under a fiduciary standard, but those higher costs would be unlikely to increase the fees clients pay.

References

Flannigan, Robert. 2004. “Fiduciary Duties of Shareholders and Directors.” Journal of Business Law May: 277–302.

Laby, Arthur B. 2008. “The Fiduciary Obligation as the Adoption of Ends.” Buffalo Law Review 56 (1): 99–167.

Joseph W. Goetz, Ph.D., AFC, CRC®, is an associate professor in the Department of Financial Planning, Housing and Consumer Economics at the University of Georgia.

Swarn Chatterjee, Ph.D., CRC®, is an associate professor in the Department of Financial Planning, Housing and Consumer Economics at the University of Georgia.

Brenda J. Cude, Ph.D., is a professor in the Department of Financial Planning, Housing and Consumer Economics at the University of Georgia, and a consumer representative to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.