Journal of Financial Planning: July 2020

Executive Summary

- Understanding what investors value and look for in a financial adviser is critical to both the client’s and adviser’s success. This research identified the alignment and discordance between what non-retired investors value, and what financial advisers think their clients value. These insights show opportunities for advisers to better articulate their value and, in doing so, improve attraction, retention, and promote client satisfaction.

- Using an online platform, investors were asked to rank a set of 15 adviser attributes from most important to least important. Advisers were asked to rank the same attributes, predicting what they thought investors valued.

- Results show that both groups recognized that reaching financial goals is a top priority, with notable disagreements on how to achieve this.

- Investors underestimated the importance of behavioral coaching in helping them stay on course. Advisers underestimated the importance of tax-efficient strategies to their clients.

- A follow-up study tested different ways of describing behavioral coaching to potentially find better wording that more naturally resonates with investors, and results suggest that simple changes in phrasing and communication can improve how investors perceive the value behaviorally attuned advisers bring to the relationship.

Ryan O. Murphy, Ph.D., is the head of decision sciences for Morningstar Investment Management. His research is interdisciplinary, bringing together methods from experimental economics, cognitive psychology, and mathematical modeling. He researches how people make decisions, especially about risk and money, and he works on developing ways to measure people’s preferences.

Samantha Lamas is a behavioral researcher at Morningstar. Her goal is to use research to better understand investors—who they are, their financial goals, and how to help them reach their goals. Her work focuses on answering impactful questions and communicating these findings to financial professionals and individual investors.

Ray Sin, Ph.D., is a behavioral scientist at Zelle who focuses on understanding how money can be sent easier, safer, and faster to your friends, family and those who you trust.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

Editor’s note: This research was originally presented at the 2019 FPA Annual Conference in Minneapolis where it received feedback from planners and academics in attendance. An earlier and abbreviated version has been released by Morningstar as part of the Investor Success Project (morningstar.com/lp/value-of-advice).

Financial advisers are under increasing pressure to communicate and demonstrate their value in the client-adviser relationship. Advisers must have answers to the increasingly common question, “Why should I work with a financial adviser versus using a robo-platform or just going with a do-it-myself approach?”

Industry research has addressed this question, measuring the impact of various adviser services on a client’s financial outcomes (Endnote 1). These findings showed how the interpersonal side of financial advice had a substantial positive impact on client outcomes. Interpersonal factors included services like behavioral coaching—helping clients mitigate potential choice biases and stay the course—and personalized/goal-centric advice, versus traditional services that focused principally on asset allocation and portfolio construction (Blanchett and Kaplan 2013). Given the ongoing commoditization of asset management, modern financial advisers are under pressure to pivot and focus on their comparative advantage over emerging approaches. To do this well, advisers need to understand what investors look for when they engage with a financial adviser.

This paper focuses on three questions: (1) What do investors look for and value when they engage with a financial adviser? (2) What do financial advisers think that investors are looking for and value when they engage with a financial adviser? (3) Are there overlooked sources of value that advisers can better emphasize and communicate as they craft and express their value proposition?

To address these questions, two research studies were conducted. The first identified the overlaps/disconnects between what non-retired investors value in professional financial advice and what advisers believe investors value. The second study was an experimental test of different ways of describing behavioral coaching. The purpose was to find what, if any, kinds of wording/phrasing are perceived as more valuable by investors. The results could potentially help advisers identify opportunities to attract, retain, and satisfy their clients, and concordantly avoid disappointment and conflicts that result from misaligned expectations. Furthermore, the results can aid financial advisers as they tailor their value proposition to better resonate with investors, and in doing so, effectively highlight key parts of their value proposition.

Literature Review

Historically, there has been confusion regarding the role of a financial adviser (Haslem 2010). One possible reason why is because advisers have had the flexibility to specialize in specific areas and/or provide comprehensive financial planning to their clients. Although this can be seen as a positive aspect of financial planning—given that it provides individuals with a wide range of options, allowing them to choose an adviser whose expertise fits their unique needs—it may prompt some investors to group many financial professionals under the “financial adviser” title.

This research adheres to CFP Board’s description of financial planning and defines the term financial adviser as someone who engages in “… a collaborative process that helps maximize a client’s potential for meeting life goals through financial advice that integrates relevant elements of the client’s personal and financial circumstances.” (Endnote 2)

Given the complexity of a financial adviser’s role, many have struggled to measure the effectiveness of financial advisers. Some attempts to measure an adviser’s effectiveness have depended on their ability to generate returns above a market benchmark. This involved metrics like alpha and beta and defined an adviser’s value in terms of asset allocation and investment selection—which some suggest to be a narrow view of an adviser’s contributions (Overton 2008; Blanchett and Kaplan 2013; Montmarquette and Viennot-Brioty 2019).

Research in this area has made strides in measuring the overarching impact of professional financial advice. Various research studies, including Blanchett and Kaplan (2013), Hanna and Lindamood (2010), and Kinniry, Jaconetti, DiJoseph, Zilbering, and Bennyhoff (2016) have shown the increasing value of the interpersonal side of financial advice, particularly the impact of services such as personalized/goal-centric advice and ongoing behavioral coaching. This reflects the evolving role of financial advisers as they shift from managing investments to managing investors.

Blanchett and Kaplan (2013) found that interpersonal services can have a substantial impact on investor outcomes. They focused on the potential benefits of an efficient financial planning strategy for a client regarding five main topics: (1) incorporating a total wealth framework; (2) dynamic withdrawal strategy; (3) incorporating guaranteed income products; (4) tax-efficient allocation decisions; and (5) portfolio optimization for liabilities. They found that improving decisions across these factors can generate 22.6 percent more expected income compared to a simplistic static withdrawal strategy, which is essentially equivalent to an increase in alpha of 1.59 percent.

Hanna and Lindamood (2010) compared the impact of expert financial planning decisions (that one would expect from a professional financial planner) to naïve decisions regarding spending and saving plans, insurance purchases, and asset allocations. They found that although the value of advice varied based on a client’s risk aversion and amount of wealth, expert financial planning advice can substantially increase a client’s wealth, prevent losses, and smooth consumption.

Kinniry et al. (2016) quantified the value of seven key adviser services: (1) asset allocation advice; (2) cost-effective implementation; (3) rebalancing; (4) asset location advice; (5) spending strategy; (6) navigating total return versus income investing; and (7) behavioral coaching. They found that advisers can generate about 3 percent to their clients’ net returns by providing each of these services. However, the most impactful service was behavioral coaching, bringing about 150-plus bps to the client. In other words, the most important service an adviser offered was behavioral coaching, which they defined as helping clients stick to their financial plan.

Grable and Chatterjee (2014) also looked at the impact advisers can have by helping clients stay calm during market volatility. The researchers tracked changes in wealth of Americans ages 45 to 53 from 2007 to 2009. They found that individuals who had professional financial advice during that time experienced a 20.89 percent reduction in wealth volatility during that period, resulting in a risk-adjusted performance advantage of about 6 percent.

Although research concerning the value of financial advice has emphasized the impact the interpersonal side of financial advice can have on a client’s performance, these findings have not trickled down to individual investors. Dimensional Fund Advisers’ Global Investor Insights Study (Endnote 3) gathered responses from 19,000 investors from eight countries and found some seemingly contradictory insights.

When investors were asked to “Choose the attribute you consider most important in your adviser relationship,” the top responses were investment returns and client service experience. However, when investors were asked, “How do you primarily measure the value received from your adviser?” the top responses were “sense of security/peace of mind,” and “knowledge of my personal financial situation.” These two questions seem to separate an investor’s expectation of a client-adviser relationship and what they value in their own relationship with their adviser.

Although investors seem to later appreciate the value of the interpersonal side of the relationship, they continue to only expect financial advisers to help them generate returns. In other words, investors seem to overlook some major sources of value that stem from financial advice. Therefore, this research attempts to further understand how investors view the role of a financial adviser and, specifically, how important adviser services such as personalization and behavioral coaching are to individual investors.

Study 1

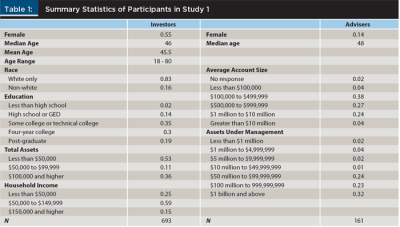

Methodology. Using an online platform, the study was conducted with two groups: financial professionals and individuals. The financial professional sample consisted of 253 professionals drawn from Morningstar’s communications database, 161 of which were financial advisers who worked directly with individual investors. This sample of 161 advisers was used in the analysis.

The sample of individuals consisted of a nationally representative sample (n = 1,066) of non-retired Americans drawn from the University of Southern California’s Understanding America Study (Endnote 4), 693 of whom were investors who owned either a 401(k), 403(b), thrift savings plan, IRA, Keogh, SEP, or investments such as mutual funds, money market accounts, stocks, certificates of deposit, or annuities. Only the sample of 693 investors was used in the data analysis for this study. The investor sample is diverse in terms of gender, household income, and amount of investable assets (see Table 1).

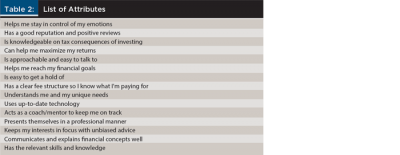

Survey details. Investors were asked what they looked for and what they found most valuable when working with a financial adviser. They were given a broad set of attributes (see Table 2) and asked to rank them in order of importance to them. These attributes were defined via a review of both academic and media resources (Kinniry et al. 2016; Rusoff 2018; Powell 2018; Hanna and Lindamood 2010; Seawright 2016; Warschauer and Sciglimpaglia 2012; Grable and Chatterjee 2014). Within the study, the term financial adviser was deliberately not defined in order to allow investors to rank the attributes according to how they think about a financial adviser. The order of the attributes was randomized per participant to mitigate potential order effects.

The online survey enlisted a direct-ranking technique that forced participants to make trade-offs between the given attributes. This ranking methodology allows for the identification of the perceived relative importance of one attribute over another and avoids the problem of people rating everything as important (which is noninformative).

The sample of advisers were asked what they thought investors found most valuable when working with a financial adviser. Advisers were given the same list of attributes and asked to rank them in order of importance from an investor’s perspective. In other words, advisers were asked to predict what clients valued from them professionally.

To analyze the results, the average rankings provided by the investor and adviser samples were calculated and used to compare the two populations. A correlation coefficient was computed to identify the level of association between the two sets of average rankings.

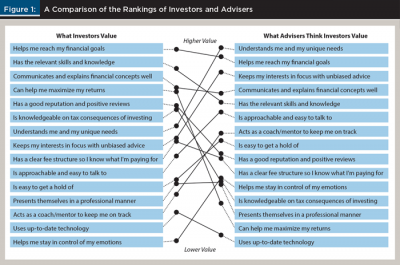

Findings. The correlation between both the average lists of advisers and investors was approximately +0.46, meaning there was a moderate positive relationship between the two sets of rankings on average.

This study’s results showed some disagreements on what was considered valuable, suggesting opportunities for advisers to better address investors’ needs. The differences in rankings also highlighted some areas where individual investors may be misunderstanding the value of professional financial advice.

Figure 1 displays the average rankings of both investors and advisers. The placement of each attribute represents its average ranking for each group, with the top of the figure showing the highest rated attribute in terms of its importance. The figure also allows for the visual representation of how much higher (or lower) one attribute was rated compared to another. For example, in the investor sample, the attribute “Helps me stay in control of my emotions” was rated as the least valuable attribute, as evident from its last place position in the ranking and its substantial distance from the other attributes.

Because the investors in the sample had less wealth then the typical adviser client, additional analyses were completed to determine if there was a difference in rankings, given the income and amount of investable assets of participants. The average ranking of participants with an income of over $100,000 (n = 256) was compared to participants with an income less than $100,000 (n = 437). The correlation between these two groups was 0.98 and thus, there was no meaningful difference in the general rankings of these two groups.

The average ranking list of participants with investable assets over $50,000 (n = 329) was compared to participants with investable assets less than $50,000 (n = 364). The Spearman rank-order correlation between these two groups was 0.97 and thus, there was no meaningful difference in the overall rankings of these two groups. Similar analyses were conducted comparing participants’ gender, age, race, education level, and experience in working with a financial adviser. The analysis found that each of the different subgroups’ average rankings were highly correlated, so again, there were no substantive differences among the rankings of these subgroups.

There are a few attributes that show manageable gaps that advisers can address. For example, investors ranked “Is knowledgeable on tax consequences of investing” much higher than advisers anticipated. Many advisers incorporate tax strategies in their investing process, and this finding may encourage them to include/invite their clients in those decisions and highlight this valuable service. Investors also rated “Has a good reputation and positive reviews” attribute a bit higher than anticipated from advisers. This result may be a useful reminder to advisers of the enduring value of professional reputation.

A few of the other discrepancies, however, may be harder to address. Advisers and investors both placed “Helps me reach my financial goals” in their top valuable attributes; however, the other top attributes displayed different priorities. Investors seemed to concentrate on the traditional services offered by financial advisers, such as aiming to generate investment returns, and underappreciated the arguably more valuable interpersonal services. For example, most investors ranked “Helps me stay in control of my emotions” last, which may be surprising given the research findings that advisers acting as behavioral coaches (e.g., helping clients control their emotions and stay on track) is the single most impactful service an adviser can offer (Endnote 5). Investors appeared not to appreciate this important source of value (more on this later).

The results also indicated that advisers overemphasize the importance investors place on personalization and having a portfolio that is tailored to their unique needs. Advisers’ emphasis on personalization goes hand-in-hand with new approaches to investing, such as goals-based investing, a strategy that can result in 15 percent more client wealth (Blanchett 2015). However, the rankings of investors suggested that investors don’t seem to value personalization or behavioral coaching, even though these two services may result in an increase in their overall wealth. It’s important to note that these findings do not indicate that advisers should conform to what investors value; instead, they call for a change in how the profession talks to clients regarding how professional financial services create value. Goal-centric advice is valuable, and this result suggests advisers may have to emphasize that goal-centric financial planning is an important and valuable kind of personalization.

Improving Communication on the Adviser’s Value

In the past, professional financial advice was promoted as being a way to beat the market, thus it’s no surprise that many investors still expected that outcome from their financial adviser. However, the additional services advisers provide have been shown to be extremely impactful, but many are underappreciated by investors. A way to address this discrepancy is better communication to help investors understand the value of these attributes.

One possible solution is to help investors shift away from thinking of investing advice as a way to maximize returns and instead encourage investors to see investing as a way to reach their financial goals. Goals-based investing is a step in the right direction, and goals-centric financial advice gives advisers an opportunity to reframe their discussions. Rather than focus on outcomes like beating an index or benchmark, advisers can refocus their client’s attention to the more personal and fundamental “why” of investing. Doing so highlights the central importance of long-term financial goals and defines good advice as guidance that helps people reach their goals.

Goal-centric framing downplays maximizing returns—that’s because focusing solely on maximizing returns can put client’s goals in jeopardy. For example, an all equity portfolio may not be prudent for a client who is five years away from retirement, even though it has the potential to maximize returns. Reframing discussions around goals (versus returns) may be a better way to articulate the value of financial advice, and this recasting may help clients align their expectations with what they should do to succeed.

Study 2

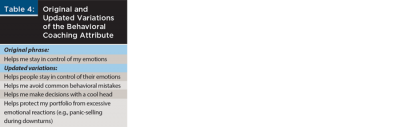

Methodology. To further investigate why investors undervalued behavioral coaching, a follow-up study was conducted to identify if this objectively valuable attribute was underappreciated because of how it was communicated.

For example, the behavioral coaching attribute used in Study 1 had the following wording: “Helps me stay in control of my emotions.” Maybe this particular wording was abrasive to investors and/or came across as pedantic. Would investors like the idea of behavioral coaching if it were described using different language? To better understand if there are more effective ways to communicate behavioral coaching, a follow-up experiment was conducted to test different ways of phrasing the behavioral coaching attribute.

A sample of 1,020 individuals drawn from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) service were asked to complete an online survey similar to the survey presented in Study 1. The MTurk default qualifications used were: participants must have a HIT Approval Rate (a measure of how many tasks they complete in the survey) of 92 percent or greater, they must have 100 or more approved HITs, and their location must be in the United States. Given that the survey took about three minutes on average to complete, participants received $0.40 for completing the survey, which complies with the federal minimum wage standard. Of this sample, 877 participants stated owning either a 401(k), 403(b), thrift savings plan, IRA, Keogh, SEP, or investments such as mutual funds, money market accounts, stocks, certificates of deposit, or annuities, so these individuals were considered investors. Only the participants who qualified as investors were included in the subsequent analysis (see Table 3).

Participants were asked to rank the same attributes as before based on what they found most valuable when working with a financial adviser. However, participants were randomly assigned to view one of five different phrases for the behavioral coaching attribute (see Table 4). The random assignment was conducted using the online survey software SurveyGizmo. Each of the five different conditions were randomly assigned 20 percent of the sample. Each phrase addressed a possible limitation of the original phrasing. For example, one version avoided the use of jargon (“helps me make decisions with a cool head”), another depersonalized the wording to avoid sounding judgmental (“helps people stay in control of their emotions”), and another gave an example of a common behavioral mistake to help investors understand its importance (“helps protect my portfolio from excessive emotional reactions like panic-selling during downturns”).

If changing how behavioral coaching is communicated has no impact, the ranking of the behavioral coaching attribute would experience little to no change in its average ranking. However, if would be worth knowing if something as simple as updated wording could help investors better appreciate the value behavioral coaching brings.

Results. This study’s results suggest that changing how behavioral coaching is communicated can help investors better appreciate the value of this attribute. Figure 2 displays the density of the rankings for the five phrases, along with the average ranking denoted by the black dot.

Although the original phrase (“helps me stay in control of my emotions”) and the depersonalized version of the original phrase (“helps people stay in control of their emotions”) continued to be ranked as the least important value offered by financial advisers, the other three phrases showed more promise among investors. The phrases “helps protect my portfolios from excessive emotional reactions (e.g. panic-selling during downturns),” “helps me make financial decisions with a cool head,” and “helps me avoid common behavioral mistakes,” had a positive impact on the ranking of the attribute and more investors rated them higher in importance.

These findings suggest that phrasing behavioral coaching in a way that offers investors examples of behavioral mistakes and avoids the idea of investors having to “control” their emotions, can help investors see the value of behavioral coaching.

Implications for Financial Planners

The results suggest that investors have fundamental misunderstandings about the value of professional financial advice. Although the job of financial advisers has evolved over the years—now providing both interpersonal and performance-based services to clients—many investors still see them primarily as investment experts (Haslem 2010).

Discrepancies in the perceived value of financial advice may be artifacts of the industry’s past self-presentation. Arguably, the field over-emphasized returns and beating benchmarks, instead of focusing on the interpersonal side of professional financial advice, with an emphasis on long-term goals and helping investors stay on track. As many studies have shown, these kinds of goal-centric and behaviorally tailored approaches are the greatest source of value that advisers provide, and these sources of value establish a clear justification for the client-adviser relationship (Blanchett and Kaplan 2013, Hanna and Lindamood 2010, and Kinniry et al. 2016). The fact that many investors don’t understand or appreciate these sources of value is a problem for investors, advisers, and the financial planning profession.

These findings call for a change in how financial advisers communicate with clients and prospective clients. Professionals can start by learning the language of the interpersonal side of financial advising. Asebedo (2019) explained how “financial planning education programs focused predominantly on technical knowledge will produce financial planners with a more limited scope of functioning” (pg. 48) and, unfortunately, many programs still neglect the interpersonal aspects of an adviser’s job. The findings of this research add to the growing discussion in the profession regarding the importance of the human side of financial planning and the need to prepare advisers accordingly. Although many advisers already engage in the interpersonal side of financial planning, many may struggle to properly explain this value to clients, which formal education regarding research and techniques may help remedy.

Another technique that may help advisers communicate this value to clients may come from highlighting where these potential pitfalls or misalignments are, allowing advisers to intelligently anticipate the kinds of misperceptions their clients might have, and work early on to build alignment around both expectations and sources of value that come from good, long-term, goal-centric financial advice.

It’s important to note that, as with any research discussing aggregate results, the values of the “average” investor may differ from the values of a particular investor. For example, some investors ranked the behavioral coaching attribute higher on their ranked lists, signaling that they may be aware of the importance of this attribute. However, on average, most investors ranked this attribute near the end of their list, signaling that they did not believe this attribute is important.

Furthermore, as every adviser knows, every investor is different. Some investors may require more emotional support, while others may be comfortable giving their adviser full reign over their portfolio. As a takeaway from this research, advisers should understand that, on average, investors seem to misunderstand some sources of an adviser’s value, but when working with a particular client, advisers should consider that client’s personal needs, understanding, and personal characteristics. Advisers should also consider that an investors’ values and needs will change over time, as a result of life events, updated market conditions, or changes in preferences (Asebedo 2019). Future research could be conducted where this study is replicated again every few years in order to build up a time series; these kinds of data would allow researchers to better understand changes and trends in what investors perceive as valuable from advisers.

Limitations

A few limitations regarding the research are worth noting. First, the investor sample used for the first study was predominantly White (n = 576), and may not be representative of the wider population. Although follow-up analyses were conducted to identify any significant difference between the average rankings of participants who self-identified as members of a racial minority (n = 114) and did not uncover any significant differences, the uneven sample sizes may have impacted these findings. Larger samples may be able to detect differences not surfaced here.

Also, the investor sample used in the first study may not adequately represent an adviser’s typical client base, given that a majority of participants had less than $50,000 in investable assets and were not retired. To identify the impact of these discrepancies, follow-up analyses were conducted to see if there were any significant differences between the average rankings of investors with less than $50,000 in investable assets compared to those with more, and no significant differences were found. The sample used did not include any retired individuals and, as a result, the findings may not be as indicative of the particular values of retired investors.

Another limitation of the research concerns the difference in the sample size of investors versus financial advisers. The relatively smaller sample size of advisers was due to the difficulty of recruiting advisers to participate in the research and may have had an impact on the overall average rankings of advisers. As is generally the case with inferential research, larger samples are useful but sometimes difficult to secure.

The MTurk sample acquired for the second study was not derived from a nationally representative panel and thus may have been different than the general population. This change in sample composition between the two studies may have undermined the ability to compare the average rankings derived in study 1 versus study 2. That being said, the findings from study 1 were replicated in study 2—the average rankings from study 1 were very similar to the average rankings in study 2 in the version that featured the same list of attributes. This gives us confidence in the results and conclusions, but ideally all of the results would have been derived from nationally representative samples.

Also, the term “adviser” was deliberately not defined in the study. This was done to allow participants to use their own understanding of what an adviser does when stating their beliefs and preferences. However, this may be seen as a limitation because some participants may have been thinking of an investment adviser versus a comprehensive financial adviser when completing the study.

Conclusions

The results of this research indicate a misalignment between what investors value from professional financial advice and advisers’ expectations of what investors value. The research suggests that there are many areas that present opportunities for advisers to better communicate their real value by emphasizing certain attributes, such as tax efficiency and behavioral coaching. The research also highlights that investors are largely unaware of the substantial value of specific adviser and planner services, for example, helping investors manage their emotions while investing. On a wider scale, the financial planning profession can help investors better appreciate the value of advice by shifting their attention to their financial goals, and simultaneously deemphasize return maximization as a focal criterion of investment success.

Endnotes

- See the 2019 Merrill Lynch whitepaper, “The Value of Personal Financial Advice,” https://behaviorquant.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Merril-Lynch-2016-The-Value-of-Personal-Financial-Advice.pdf.

- See Section B Paragraph 1 of the CFP Board Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct (cfp.net/ethics/code-of-ethics-and-standards-of-conduct).

- See “Global Investor Insights,” from Dimensional Fund Advisers at us.dimensional.com/2017-investor-survey-insights.

- For a detailed description of this panel, sample weighting techniques, and sample recruitment details, see Alattar, Messel, and Rogofsky (2018).

- See Endnote No. 1.

References

Alattar, Laith, Matt Messel, and David Rogofsky. 2018. “An Introduction to The Understanding America Study Internet Panel.” Social Security Bulletin 78 (2): 13–28.

Asebedo, Sarah D. 2019. “Financial Planning Client Interaction Theory (FPCIT).” Journal of Personal Finance 18 (1): 9–23.

Blanchett, David. 2015. “The Value of Goals-Based Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (6): 42–50.

Blanchett, David, and Paul Kaplan. 2013. “Alpha, Beta, and Now… Gamma.” The Journal of Retirement 1 (2): 29–45.

Grable, John E., and Swarn Chatterjee. 2014. “Reducing Wealth Volatility: The Value of Financial Advice as Measured by Zeta.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (8): 45–51.

Hanna, Sherman D., and Suzanne Lindamood. 2010. “Quantifying the Economic Benefits of Personal Financial Planning.” Financial Services Review 19 (2): 111–127.

Haslem, John A. 2010. “The New Reality of Financial Advisors and Investors.” The Journal of Investing 19 (4): 23–30.

Kinniry, Francis M., Jr., Colleen M. Jaconetti, Michael A. DiJoseph, Yan Zilbering, and Donald G. Bennyhoff. 2016 (revised). “Putting a Value on Your Value: Quantifying Vanguard Adviser’s Alpha.” The Vanguard Group. Latest version available at advisors.vanguard.com/insights/article/IWE_ResPuttingAValueOnValue.

Montmarquette, Claude, and Nathalie Viennot-Brioty. 2019. “The Gamma Factors and the Value of Financial Advice.” Annals of Economics & Finance 20 (1): 387–411.

Overton, Rosilyn H. 2008. “Theories of the Financial Planning Profession.” Journal of Personal Finance 7 (1): 13–41.

Powell, Robin. 2018. “What Clients of Financial Advisers Really Value.” Evidence Investor. Available at evidenceinvestor.com/what-clients-financial-advisers-value.

Rusoff, Jane W. 2018. “Top 3 Adviser Traits Clients Value Most.” ThinkAdvisor. Available at thinkadvisor.com/2018/01/03/top-3-advisor-traits-clients-value-most.

Seawright, Bob. 2016. “A Hierarchy of the Value a Financial Adviser Provides.” Nerd’s Eye View. Available at kitces.com/blog/hierarachy-of-financial-adviser-value.

Warschauer, Thomas, and Donald Sciglimpaglia. 2012. “The Economic Benefits of Personal Financial Planning: An Empirical Analysis.” Financial Services Review 21 (3): 195–208.

Citation

Murphy, Ryan O., Samantha Lamas, and Ray Sin. 2020. “Identifying What Investors Value in a Financial Adviser: Uncovering Opportunities and Pitfalls.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (7): 44–52.