Journal of Financial Planning: March 2011

In 1992, the late James Bond Stockdale posed two memorable inward-looking questions before a nationwide television audience. They are the same questions that financial planners need to ask—and answer—before attempting to reach a new or larger audience:

“Who am I?”

“Why am I here?”

Stockdale was the vice presidential running mate of Ross Perot in the latter’s independent bid for the White House 19 years ago. Stockdale, a highly decorated Navy fighter pilot, eight-year Vietnam-era POW captive, retired vice admiral, and political rookie unknown to most Americans, had a realistic picture of the biggest questions that would be on voters’ minds as they regarded him for the first time.

For planners, the value of posing and answering those questions to their own satisfaction today—before they face the public anew—is to ensure that their businesses are built on a foundation of authentic purpose. The self-defeating impulse planners must overcome, marketing-savvy veterans report, is to select and implement marketing tactics before they have developed a strategy on the foundation of who they are, and why they are here.

The process does not require a psychotherapist, but the ultimate results can be psychic as well as pecuniary. What typically prompts planners to begin thinking about the need for a marketing plan is not their psychological health, but a dawning recognition that their businesses are languishing, or at least could be doing a lot better.

Signs It’s Time to Retool

A few years ago Marc S. Freedman, CFP®, president of Freedman Financial in Peabody, Massachusetts, was beginning to think about the ultimate transition in leadership of the firm his father Barry M. Freedman, CFP®, had founded in 1968. “We needed to be a bit more business-minded and analytical in our approach to make sure we were running the business efficiently and that we had fair value for the business,” he recalls.

That led to a startling revelation. “One day, a virtual anvil fell on me, and I was sickened by the reality that our business was not profitable, and it was, at best, adequately managed,” he wrote in his 2008 book, Oversold and Underserved: A Financial Planner’s Guidebook to Effectively Serving the Mass Affluent (FPA Press).

But instead of cranking up the standard machinery of practice marketing, Freedman took a different approach: he engaged a consultant “to help us better understand the purpose of our practice and determine a way to retool it so that it reflected our core values and helped us become more profitable,” he writes.

Meanwhile, the catalyst for professional introspection and strategy fine-tuning that led to a new marketing effort by Frank Patzke, CFP®, of Guidant Wealth Advisors in Palatine, Illinois, was the resignation of a junior planner on his staff who took several clients with him. “I was enraged,” Patzke recalls. And it wasn’t the first time that had happened to Patzke; a similar event had occurred several years previously. His anger was not ultimately directed at his former associate, but at himself for his failure to manage his practice in such a way that the individual didn’t feel the need to leave.

Perhaps a more typical impetus for a strategic marketing review is the situation that Bruce J. Berno, CFP®, of Berno Financial Management in Cincinnati, Ohio, found himself in: “My growth was flattening out. My referral sources were drying up.” When Berno began his fee-only practice in 1993, fee-only planners were a scarce commodity in the Cincinnati area. In recent years his competition had intensified, and he knew he needed to rethink his business in order to forestall client atrophy.

Calling for Help

The situations described above are typical of what prompts planners to contact practice management experts, such as Kevin Poland, a Tampa, Florida-based consultant/coach and founder of The Renaissance Group. Other typical situations Poland has experienced:

- Multiple advisers/principals of the firm have been operating like silos, and now are ready to run the practice as a real business

- Transition from broker-dealer-based services to an RIA model

- The owner is gearing up to retire and wants to beef up the practice to make it more attractive to a prospective buyer

Because developing and executing a strategic marketing effort is, for many planners, less fun than a visit to the dentist, “Their pain must be clearer to them than what they’re trying to accomplish,” Poland says.

If a planner contacts him asking for help in developing a marketing plan, Poland says his initial response is: “Tell me why you think you need a marketing plan.” In other words, he wants to be sure that planners are willing to dig into the “Who am I? Why am I here?” discussion before attempting to dispense easy solutions. (See the sidebar “Who Needs Consultants?”)

The process of looking under all the rocks of a practice may reveal that what the planner ultimately seeks—for example greater profitability—may not be attainable through simply drumming up more clients like the ones he or she already has. It may require a new kind of client altogether.

In addition, planners may simply assume they need to grow without reflecting on the ultimate purpose of growth. “There’s a lot of peer pressure to grow,” notes Ginny Hudgens of Baton Rouge, Louisiana-based Back Office Advisor. “You can’t go to a conference without seeing all these sessions on how to grow your business. You need to really understand your motivation before you start a marketing plan,” she adds. After reflecting on her initial desire for a marketing push, one of Hudgens’s prospective clients dropped the whole idea. “She realized that she was actually happy with where she was,” she says.

When Marc Freedman went through the same initial probing process, he drew the conclusion that he did need to go forward with a thorough market discovery process. “It is more tempting to find another niche than fix your mess,” he concedes in his book. “You can’t just say, ‘Let’s try this [marketing strategy] for a while.’ It has to start with your core values.”

A Natural Market

Freedman’s core values were not entirely clear to him until he methodically took stock of his client base to look for patterns. “When the firm was started, we took on anyone who could fog a mirror,” he says. But his analysis of his core client base revealed a demographic and psychographic pattern that Freedman has deemed the “mass affluent.”

While the term “mass affluent” has been used in marketing circles since the 1970s, for Freedman’s purposes, it largely refers to middle-aged, stable, and intact families of above average income and assets who are serious about achieving financial goals. He draws a distinction between that group and the larger “middle market,” which he defines as people with similar economic potential, but who lack the values or discipline to achieve a reasonable level of financial success.

With a clear vision of his natural client base, Freedman could begin to build a strategy to optimize his services to that group and, in the process, improve the profitability and efficiency of his business. In effect, his “marketing” strategy was to align his business synergistically around his natural market, and diplomatically transition out clients who didn’t fit into that segment. That process included setting minimum annual fees to address the problem he discovered after a client-by-client profitability analysis: 30 percent of collective staff time was dedicated to a set of clients who brought in only 1 percent of the firm’s revenue.

One of his new core principles was that “every new client coming in was going to have a financial plan done, and they were going to pay us for it,” Freedman says. “We no longer wanted to be seen just as ‘the investment guys.’” Freedman insists that if someone walked into his office today and declared that he had $50 million, but only sought investment management services, he would not be tempted to take him on as a client.

A strategic review does not inevitably lead to a decision to sharpen one’s market segmentation. Frank Patzke, the planner who lost clients when junior associates left the firm, makes a conscious choice of taking on “anybody who wants to be a client.” That guiding principle, he says, stems in part from growing up in a blue collar family that could have benefitted from the kind of financial advice he gives his clients today.

“We needed more help than millionaires did,” he recalls. Patzke was an only child; his father died at age 50, when Frank was 15, which forced him to get a job to support his widowed mother.

Patzke says he could establish a high minimum asset threshold for clients today, but doesn’t. As a result, he says, “I have to make willful decisions about how I’m going to build my business to permit me to [take on clients of modest means]” while still running a profitable practice.

In the process of analyzing his own client base, Patzke couldn’t help but notice that he had many widows. From his childhood experience, he had a natural affinity for them—and understood their needs. They are a natural client because their husbands usually managed the money and didn’t equip their wives to take on that role after their deaths. And even if they had an opportunity to learn how to manage money, “often they didn’t want to,” in Patzke’s experience.

He and his widow clients have developed strong personal ties, he says. The relationships often lead to his taking on their children as clients. “That’s how I perpetuate my business,” he says.

Nonetheless, Patzke decided he needed to become much more deliberate about sustaining his business through a formal marketing effort in order to ensure a steady stream of “A” clients to allow him to continue serving “C” and “D” clients. And he decided that if the firm was to live on beyond himself—a goal he has set—it needed a name that didn’t include his own. A survey of his clients showed that they viewed him as a trusted guide, which led him to rename his firm “Guidant Wealth Advisors.”

Staff Alignment

Other marketing steps Patzke has undertaken center on branding his firm and improving the client experience. For example, his seven-member staff now includes a “client concierge” whose duties include remembering what clients like to drink and preparing it for them when they visit the office. All staff members have titles that reflect their roles so clients can understand what they do.

Patzke has also agreed to and acted upon a marketing consultant’s recommendation that he produce well-designed brochures and pick a color palette for marketing materials and even the color of his office walls. Yet Patzke cautions that marketing tactics should never become the tail that wags the dog: “You have to be true to yourself. If you’re false, people will know it.”

Patzke’s ultimate marketing goal is to build relationships with people, both to solidify the relationship and to inspire clients to send him referral business. To do so, he says, “We spend inordinate amounts of time in our client meetings.” He also has entered the social media fray, noting that many of his older women clients use Facebook to stay in touch with their grandchildren. “If I can access it in a way that’s attractive to them, that’s the kind of thing we do in our marketing.” (He leaves the actual mechanics to a new marketing manager on his staff.) Despite the resource commitment, Patzke has found this approach more productive than cultivating attorneys and accountants as referral sources.

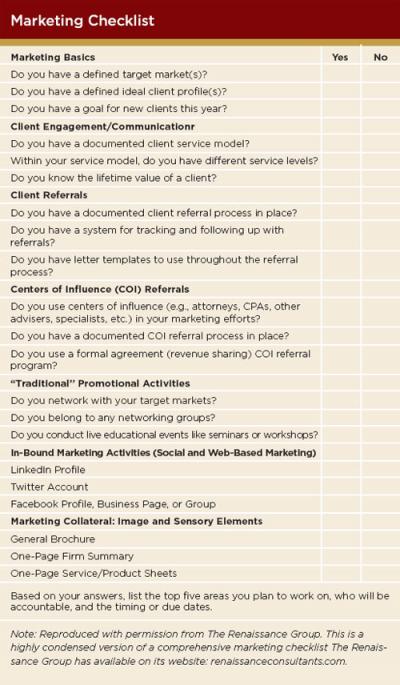

One way or another, a significant time commitment is inherent in devising and executing a strategic marketing effort. (See the sidebar “Marketing Checklist.”) For Bruce Berno, a significant proportion of his marketing time has been dedicated to coaching sessions with Kevin Poland. “I’ve never been a salesman,” Berno says. Prior to launching his own financial planning practice, he worked for a bank trust department, where his income was not directly dependent on bringing in business.

In laying the groundwork for his marketing strategy Berno concluded that, unlike Patzke, his current goals do not include building an organization that will live on after he retires. “For the next 5 or 10 years, it’s just going to be me,” he says. Therefore, his marketing goals involve maintaining as many clients as he can, and having just enough new ones come in to replace the few that leave or fade away.

Marketing for the Non-Salesperson

Berno has always targeted clients in their 40s and 50s whose financial lives usually are more complicated than those younger or older than middle age. Now that he has joined that age bracket himself, he has found that his natural market includes a lot of the people with whom he interacts personally. As a self-proclaimed non-salesman, Berno has been gratified to discover that he can be more effective at winning over new clients by doing more listening and less “telling them how good we are.”

Kristen Luke, the principal of San Diego-based Wealth Management Marketing, offers reassuring and empowering words to the non-salesperson crowd. “Marketing has this negative connotation, especially for some fee-only planners,” she says. “But educating is how everyone should think about marketing. And how can you help anybody if they don’t know about you? I think of marketing as relationship building and education. It doesn’t have to be ‘sales-y.’”

Obviously, the subject of the “education” has to be compelling to the prospective “students.” For Mark C. Bronfman, CPA, a private wealth adviser with Sagemark Consulting in Vienna, Virginia, the way to cut through the competition is to go, as he calls it, “hyper-nichey.”

Bronfman, a former business strategy consultant with Accenture, took to heart the lessons of the 2005 bestseller Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make Competition Irrelevant. The popular book draws on the naval warfare analogy: blue oceans are free of enemy ships, in contrast to red oceans, where one must constantly engage in bloody battles to survive. The uncontested “blue ocean” that Bronfman is trolling involves a blend of corporate finance, strategy, succession planning, and executive compensation expertise combined with the standard personal financial planning disciplines of investments and estate planning.

Bronfman says that narrowing his market target dramatically from a “manna from heaven” scattershot approach to only bull’s eye prospects (owners of businesses with revenues of at least $50 million) has dwarfed in significance everything else he had previously done to market his services. With his hyper-niche clearly in the cross-hairs, Bronfman has been blasting away with public speaking engagements, event sponsorships, webinars, and “thought leadership” demonstrations, such as publishing the article “The Art of Resilient Capital Planning for Executive Compensation, Estate Planning, and Philanthropy” in the July 2009 Journal of Financial Planning.

Bronfman says that one of his personal motivations behind his hyper-niche strategy was to develop a “hyper-local” practice. In that way, Bronfman joins company with Freedman, Patzke, and Berno in his effort to structure his business, and the marketing strategy that flows naturally from it, in harmony with his personal values and beliefs. Sometimes marketing efforts include specific numeric goals—revenue, assets under management, number of clients, and so on. But knowing “who I am and why I am here” leads to a more visceral sense of mission accomplished.

Richard F. Stolz is a financial writer and publishing consultant based in Rockville, Maryland.