Journal of Financial Planning: March 2014

John B. Shoven, Ph.D., is the Trione Director of the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research and the Charles R. Schwab Professor of Economics at Stanford. He is also a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research, and a member of the board of directors of Financial Engines. Email John Shoven.

Sita Nataraj Slavov, Ph.D., is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Previously, she was an associate professor of economics at Occidental College and a senior economist at the Council of Economic Advisers. Email Sita Slavov.

Acknowledgments: This research was supported by the U.S. Social Security Administration through grant #5RRC08098400-05-00 to the National Bureau of Economic Research as part of the SSA Retirement Research Consortium. The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of SSA, any agency of the federal government, or the NBER. The authors are grateful to Sindy Li and Brittany Pineros for outstanding research assistance; to David Weaver, Henry Aaron, and participants at the SIEPR Working Longer and Retirement Conference for helpful discussion and comments; and to Steve Goss, Michael Morris, and Alice Wade of the SSA for providing the cohort life tables used in this paper. Financial Engines provided no financial support for this research.

Executive Summary

- Social Security retirement benefits can be claimed at any age between 62 and 70, with delayed claiming resulting in larger monthly payments.

Claiming Social Security benefits later generally increases the present value of lifetime benefits for most individuals. - During the late 1990s and early 2000s, a number of policy changes increased the gains from delay, particularly for couples. In addition, mortality improved and real interest rates fell considerably over this period, further increasing the attractiveness of delay.

- For the purposes of this study, simulations to examine the role of these factors in changing the gains from delay were performed. Findings suggest that the gains from delay increased substantially after 2000, with changes in the interest rate playing the largest role in driving the increase.

Social Security retirement benefits can be claimed at any age between 62 and 70, with delayed claiming resulting in larger monthly payments. These larger payments represent an actuarial adjustment to account for the fact that an individual who claims later is likely to receive benefits for a shorter period. Shoven and Slavov (2013a) investigated the actuarial fairness of this adjustment in light of recent low real interest rates combined with improved mortality and concluded that delaying Social Security is actuarially advantageous for most individuals. Delay is particularly beneficial for the primary earner in a couple; however, even singles with mortality rates that are substantially above average can benefit from delay at near-zero real interest rates like those that have prevailed for much of 2013 and early 2014. The Shoven and Slavov study also demonstrated that the gains from delay have increased greatly—particularly for couples—since the early 1960s, when delays first became available.

Besides falling interest rates, a number of benefit rule changes in the 1990s and early 2000s have contributed to the attractiveness of delaying Social Security. For example, prior to 2000, a non-earning spouse in a married couple could not claim a spousal benefit until the primary earner had claimed his or her worker benefit. Thus, delaying the primary earner’s benefit forced the non-working spouse to delay as well. Since 2000, however, married individuals have been able to claim spousal benefits when their spouse reaches full retirement age or claims benefits, whichever is sooner. In addition, the delayed retirement credit (the adjustment for delaying Social Security beyond full retirement age, which was 65 for those turning 62 in 1992, and has risen to 66 for those turning 62 today) has become much more generous.

In this paper, we investigate the impact of these recent rule changes on the gains from delay for a variety of stylized couples. An attempt is made to isolate the effects of these rule changes from the effects of the interest rate and mortality changes that have also occurred over the past two decades. Results suggest that the rule changes by themselves have increased the gains from delay, which are measured as the percent increase in the net present value of benefits from optimal delayed claiming relative to claiming at 62, by about 1 to 2 percentage points for singles, 5 to 6 percentage points for two-earner couples, and 2 to 4 percentage points for one-earner couples.

Most of this increase is attributable to the rise in the delayed retirement credit. Interest rate and mortality changes further increase the gains from delay for younger cohorts relative to older ones.

The combination of rule changes, mortality changes, and interest rate changes has greatly increased the gains from delay for cohorts born in 1938 and later (that is, individuals turning 62 in 2000 and later), with interest rates playing the largest role. These insights are valuable for financial planners because they provide a better understanding of the extent to which the gains from delay are influenced by economic and demographic factors on the one hand, and Social Security rules on the other. Findings suggest that the decision of when to claim Social Security has changed quite dramatically over the past two decades.

To put these results in context it is worthwhile to note that Shoven and Slavov’s (2013a) conclusions about the gains from delay for two-earner couples relied on a somewhat unusual claiming strategy; namely, one spouse claims spousal benefits starting at full retirement age (age 66), while allowing his or her own worker benefit to grow through delay.

For example, a present-value maximizing claiming strategy might involve the primary earner claiming a spousal benefit starting at age 66, then switching to his or her own benefit at age 70, while the secondary earner claims a worker benefit at age 62. Thus, the primary earner can effectively get paid during the delay period. The availability of this strategy is likely unintentional, arising from a system designed with one-earner couples in mind.

This claiming approach is not well known and is rarely used. Thus, we investigate how the gains from delay are altered if this strategy is made unavailable. We find that the gains from delay (again, measured as the percent increase in net present value from optimal delay relative to claiming at 62) fall by about 4 to 5 percentage points for two-earner couples if this strategy is eliminated.

It is important for financial planners to understand the impact of these strategies, as well as how claiming approaches interact with interest rates, client demographics, and other Social Security rules.

Prior Research

A number of prior studies have established that a large subset of individuals stand to gain from delaying Social Security (Coile, Diamond, Gruber, and Jousten 2002; Munnell and Soto 2005; Mahaney and Carlson 2007; Sass, Sun, and Webb 2007; Meyer and Reichenstein 2010). The main conclusion is that the gains from delay are particularly large for primary earners in married couples, because when a primary earner delays Social Security, it boosts the survivor benefit that the secondary earner would receive in the event of widowhood.

Delaying Social Security may also have tax advantages (Mahaney and Carlson 2007), and the utility gain from delay may exceed the expected monetary gain due to the insurance value of the Social Security annuity (Sun and Webb 2009). Shoven and Slavov (2013a) revisited this issue in the context of historically low interest rates, demonstrating that delay increases the present value of benefits for most people. This finding applies not only to primary earners, but also to singles, even those with mortality that is much greater than average. In addition, the gains from delay have increased dramatically since the early 1960s, when delay first became available, as a result of interest rate changes, mortality improvements, and (for couples) law changes.1

Empirical studies have shown that although there is some evidence that those who benefit from delay are more likely to do so (Coile et al. 2002; Munnell and Soto 2005; Beauchamp and Wagner 2013), the vast majority of people claim as early as possible, even when it appears to be clearly suboptimal (Hurd, Smith, and Zissimopoulos 2004; Sass, Sun, and Webb 2007, 2013).

Among those who stop working before age 62, there is not much of a relationship between claiming age and the factors that influence the gains from delay (Hurd et al.). Field experiments suggest that while providing factual information about the gains from delay does not appear to alter claiming decisions (Liebman and Luttmer 2011), self-reported claiming intentions are sensitive to the way in which the claiming decision is framed (Brown, Kapteyn, and Mitchell 2011).

Our current work investigates the extent to which the gains from delay have changed since the 1990s. In doing so, we reconcile the results of studies that focused primarily on cohorts born in the 1930s and early 1940s (for example, Coile et al. 2002; Sass, Sun, and Webb 2007, 2013) and found more modest gains from delay with those of studies that focused on younger cohorts (for example, Meyer and Reichenstein 2010; Munnell and Soto 2005; Shoven and Slavov 2013a). Together, these studies suggest that delay is more advantageous for cohorts approaching age 62 today, compared to those approaching 62 in the 1990s and early 2000s. In this paper, a detailed analysis of the factors underlying this shift is provided, decomposing the change in the gains from delay into the components attributable to benefit rule changes on the one hand, and to economic (interest rate) and demographic (mortality) changes on the other.

In addition, some studies (Munnell, Golub-Sass, and Karamcheva 2009; Shoven and Slavov 2013a) have relied upon a somewhat unusual claiming strategy for two-earner couples. The strategy assumed that one spouse (typically the primary earner) claims a spousal benefit starting at full retirement age, allowing his or her own worker benefit to grow through delay until age 70. The other spouse then simply claims his or her own worker benefit. Effectively, one member of a two-earner couple can use this strategy to receive a Social Security payment during the delay period. As spousal benefits were originally designed with one-earner couples in mind, it is unlikely that policymakers intended for this claiming strategy to be available to two-earner couples. Because this strategy is not well known and rarely used, other studies of the gains from delay did not take this strategy into account.

This paper sheds light on the importance of this assumption by providing a detailed analysis of the effect that this strategy has on the gains from delay for two-earner couples. Our calculation is complementary to that of Munnell et al. (2009, 2012). They computed optimal claiming strategies for a sample of couples both with and without “file and suspend” and the two-earner couple spousal benefit option. Munnell et al. (2012) estimated that the availability of these options could cost Social Security $0.5 billion and $10 billion per year respectively. This paper extends their work by showing how these strategies have affected the gains from delay for couples over the past two decades, and how claiming strategies interact with other factors such as the interest rate and mortality.

Social Security Benefit Formula

Before describing the methodology, it is useful to review the Social Security benefit formula. Retired worker benefits are based on an individual’s average indexed monthly earnings (AIME), which is defined as the average of the highest 35 years of an individual’s earnings, indexed for economy-wide wage growth. A progressive formula is then applied to the AIME, resulting in the worker’s primary insurance amount (PIA), which is the monthly benefit the worker can receive if he or she claims at full retirement age.

The PIA is calculated in the year the worker turns 62 and is indexed for inflation in subsequent years. Workers may claim benefits as early as age 62, but claiming before full retirement age results in an actuarial reduction. For individuals with a full retirement age of 65, claiming benefits at age 62 results in a monthly benefit of 80 percent of PIA. For individuals with a full retirement age of 66, claiming benefits at 62 results in a monthly benefit of 75 percent of PIA.

Workers may alternatively claim benefits as late as age 70, receiving a delayed retirement credit for each month of delay beyond full retirement age. The delayed retirement credit varies depending on the worker’s year of birth. In particular, it has become more generous for younger cohorts, with workers born in 1930 receiving 4.5 percent of PIA per year of delay, and workers born in 1943 and later receiving 8 percent of PIA per year of delay.2

As the foregoing discussion suggests, the Social Security Administration typically characterizes claiming before full retirement age as claiming “early,” and claiming after full retirement age as “delaying.” Similarly, the adjustment made to benefits claimed before full retirement age is typically referred to as a “reduction,” while the adjustment made to benefits claimed after full retirement age is referred to as a “credit.” This framing makes no difference to the mathematical calculation of benefits or their present value under different claiming strategies. To avoid confusion, therefore, we characterize all claims made after age 62 as “delays” and all increases in the present value of benefits relative to claiming at age 62 as “gains.” However, it is important to acknowledge that the framing of the choice as a reward for delay versus a punishment for early claiming may influence people’s claiming decisions.

In addition to worker benefits, a married person can receive a spousal benefit equal to half of his or her spouse’s PIA, if claimed at full retirement age. The spousal benefit is reduced for claims made before full retirement age, but there is no delayed retirement credit.

An individual who claims both a spousal and a worker benefit is paid the higher of the two. A spousal benefit cannot be claimed unless the worker on whose record the benefit is based has claimed worker benefits. For example, consider a couple in which the wife is two years younger than the husband. Assume both have a full retirement age of 66. If the husband waits until age 70 to claim his worker benefit, the wife would not be able to claim a spousal benefit until age 68, even though the spousal benefit ceases to grow through delay when the wife turns 66.

However, since 2000, a provision known as “file and suspend” has allowed a worker to file for his or her own benefit at full retirement age (or later) and then suspend the benefit. In this example, the husband could file for his worker benefit at age 66 and then suspend his benefit until age 70. The husband’s benefit would continue to grow through delay, but the wife could claim a spousal benefit at age 64. Clearly, the introduction of “file and suspend” has made it less costly for a married person to delay his or her own benefit, as doing so no longer forces a spouse to delay the spousal benefit.

A widow can also receive a benefit based on his or her deceased spouse’s record. The widow benefit is equal to either 82.5 percent of the deceased spouse’s PIA, or the deceased spouse’s actual benefit, whichever is greater. Because the widow benefit is linked to the deceased spouse’s actual benefit (including any reduction for early claiming or delayed retirement credits), the widow benefit rises when the deceased spouse delays claiming. The widow benefit is reduced if it is claimed before the widow’s full retirement age (which is not always the same as the retirement age for worker and spousal benefits), but there are no credits for delaying widow benefits beyond full retirement age.3 As with the spousal benefit, an individual who claims both a worker and a widow benefit receives the higher of the two amounts.

Methodology

To proceed with the analysis, we computed the expected net present value (NPV) of benefits from a large number of Social Security claiming strategies for various stylized households. The methodology used here is similar to that described in Shoven and Slavov (2013a).

We considered single male and female households with birth years ranging from 1930–1951 at three-year intervals. We also considered both one-earner and two-earner couples in which the primary earner (assumed to be the husband) has a birth year ranging from 1930–1951 at three-year intervals. The secondary earner (or non-earner, for one-earner couples) was alternatively assumed to be either two years or seven years younger than the primary earner. The two-year age difference was intended to represent a typical couple, while the seven-year age difference was intended to illustrate how larger age differences may alter gains from delay.

In the two-earner couple households, the secondary earner’s PIA was assumed to be 75 percent of the primary earner’s PIA. Because all monthly benefit amounts were calculated as a percent of PIA, all net present values in the analysis can be expressed as a multiple of the primary earner’s PIA. In other words, the actual levels of the stylized workers’ PIAs do not affect the optimal claiming strategies or the percent gain from delay.

In calculating NPVs, we needed to choose an appropriate discount rate. Because Social Security is an inflation-indexed obligation of the U.S. government, the most appropriate discount rate would be the interest rate on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS), which are also an inflation-indexed obligation of the U.S. government. Interest rate data are available for TIPS of varying terms, including 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30 years. For an individual, the appropriate time horizon for discounting a stream of Social Security benefits is roughly 20 years. Therefore, whenever possible, we used the average annual yield on 20-year TIPS in the analysis. For 2013, we used the average TIPS yield in the first half of the year. Prior to mid-2004, 20-year TIPS were not available. Thus, for 2004 and earlier, we used the difference between the average annual yield on (nominal) 20-year Treasury bonds and the annual percent change in the consumer price index for all urban consumers.4

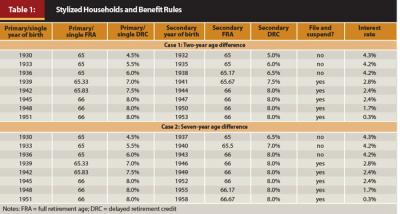

Table 1 summarizes the details of each of the stylized households. The first column of the table is the year of birth for the single person or primary earner. For this individual, the second and third columns provide the full retirement age and the delayed retirement credit (as a percentage of PIA) that is earned for each year of delay beyond full retirement age. The next three columns provide the same information for the secondary earner (or non-earner) in the couple households. The next column indicates whether “file and suspend” was available when the primary earner in the household turned 62. The last column indicates the prevailing safe real interest rate when the primary earner turned 62.

A claiming strategy for a single person consists of an age at which to claim benefits. For one-earner couples, a claiming strategy includes an age for the primary earner to claim worker benefits and an age for the secondary earner to claim spousal benefits.

For two-earner couples, a claiming strategy includes an age for each spouse to claim worker benefits. In addition, as previously discussed, we allowed the possibility of an unusual claiming strategy; namely, one member of the couple can claim a spousal benefit before claiming the worker benefit. This strategy is available as long as both worker and spousal benefits are delayed to full retirement age or later. If the spousal benefit is claimed before full retirement age, Social Security’s rules require that the worker benefit be claimed at the same time. Although delays may occur in increments of one month, to reduce the number of strategies to consider, we assumed all claims are made on birthdays.5

Strategic claiming for widow benefits was not considered. A widow was assumed to claim the widow benefit immediately upon the death of the spouse.6

For each claiming strategy and for every possible age at death (or the combination of ages at death for couples), we computed the NPV of the household’s stream of benefits using the applicable real interest rate. These benefit streams were discounted to the year in which the primary earner or single turned 62.

We then computed the expected NPV for the claiming strategy across all possible ages at death. The probability distribution over ages at death was based on the Social Security Administration’s latest cohort mortality tables, which were used for the intermediate projections in the 2013 Trustees Report. All deaths were assumed to occur halfway through the year. For couples, the deaths of the husband and wife were assumed to be independent events.

For each stylized household, we first computed the optimal claiming strategies and the gains from delay under the actual interest rate and mortality faced by that household. For couples, we performed this calculation both with and without “file and suspend.” Then, we re-computed the optimal claiming strategies for each household holding mortality and interest rates constant. In particular, we assumed a real interest rate of 2.9 percent (the long-term real interest rate assumed by the Social Security trustees) and mortality equal to that faced by the 1951 (for primary earners and singles), 1953 (for secondary earners who are two years younger), and 1958 (for secondary earners who are seven years younger) birth cohorts.

In each case, for two-earner couples, we determined the optimal claiming strategies and gains from delay with and without the spousal benefit option. These alternative calculations allowed us to evaluate the relative effects of rule changes versus interest rate and mortality changes. This approach also allowed us to isolate the effect of “file and suspend” compared to the other rule changes (increases in the full retirement age and the delayed retirement credit). In addition, we could then quantify the effect of the spousal benefit claiming strategy for two-earner couples.

Results

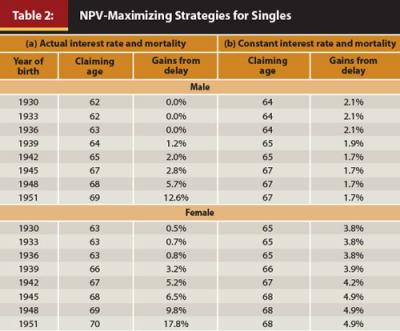

Panel (a) of Table 2 shows the NPV-maximizing claiming ages for single males and females, as well as the percent increase in NPV from claiming optimally versus claiming at age 62.

Men born before 1939 receive no benefit from delay, and the gains for women born in this period are small. Starting with the 1939 birth cohort, however, the gains from delay begin to increase for both men and women.

Men born in 1951 (who turn 62 in 2013) maximize NPV by claiming at 69, and receive a gain of 12.6 percent from following that strategy. Similarly, women born in 1951 maximize NPV at 70 and receive a gain from delay of 17.8 percent.

Multiple factors underlie the changes in the gains from delay shown in panel (a) of Table 2, including mortality improvements, a decline in real interest rates, and benefit rule changes. To isolate the effect of benefit rule changes, panel (b) of Table 2 presents the gains from delay for single men and women using the mortality rates of the 1951 birth cohort, and a real interest rate of 2.9 percent. The increase in the gains from delay is more modest in panel (b). For male cohorts born in 1942 and earlier, and for female cohorts born in 1939 and earlier, delay beyond full retirement age reduces NPV. Thus, the changes in the gains from delay for these cohorts result solely from changes in the full retirement age. For later cohorts, the increase in the delayed retirement credit plays a role.

The three most recent cohorts all face a delayed retirement credit of 8 percent and receive gains from delay ranging from 1.7 percent (for males) to 4.9 percent (for females). Despite the more modest gains from delay shown in panel (b), the gains from delay are not trivial for these recent birth cohorts, particularly for women. These calculations suggest that even if interest rates return to their historical average over the next decade or two, singles in the 1951 birth cohort will still enjoy a reasonable gain from delay.

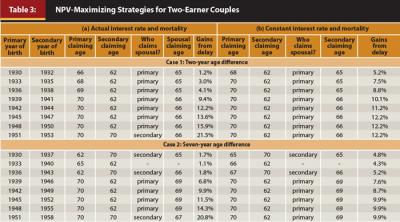

In panel (a) of Table 3, the analysis turns to two-earner couples, presenting the NPV-maximizing claiming strategies and associated gains from delay under actual interest rates and mortality. Again, the gains from delay have risen dramatically, from a modest 1 percent to 2 percent for the 1930 primary earner birth cohort to more than 20 percent today.

The results in panel (a) of Table 3 assume the availability of “file and suspend,” but removing this option barely alters the results. In particular, “file and suspend” matters only for a couple with birth years of 1951 and 1953. This couple relies on the husband filing and suspending his benefit at age 68, allowing the wife to claim a spousal benefit when she is 66. Both members of the couple then delay their own benefit to age 70. Without the “file and suspend” option, the couple’s NPV is maximized when the secondary earner claims at 64, allowing the primary earner to claim a spousal benefit from ages 66 through 69.

Under this second-best option, the gains are only 0.3 percentage points lower. This finding is consistent with that of Munnell et al. (2009) who estimated that “file and suspend” benefits only 27 percent of couples in their sample, and that these couples are primarily one-earner couples and couples in which the primary earner’s PIA is very large relative to the secondary earner’s PIA.

Just as for singles, much of the increase in the gains from delay for couples comes from improvements in mortality and declines in the real interest rate. To isolate the effect of rule changes, panel (b) of Table 3 shows the NPV-maximizing strategies for the two-earner couples assuming a real interest rate of 2.9 percent and the mortality profile of the 1951 and 1953 birth cohorts (for the top panel) and the 1951 and 1958 birth cohorts (for the bottom panel).

The gains from delay have still increased considerably for two-earner couples, although the increase is not as dramatic as that shown in panel (a). Removing the availability of “file and suspend” makes no difference to the results in panel (b). Panel (b) suggests that even if interest rates return to their historical average in the near future, two-earner couples will still enjoy large gains from delay due to rule changes and mortality.

Table 3 also suggests that, generally speaking, a couple with a two-year age difference gets larger gains than a couple with a seven-year age difference. This result runs counter to conventional wisdom, which suggests that the gains from delay increase with the age difference between the primary and secondary earners (see, for example, Coile et al. 2002).

The intuition behind the conventional wisdom is straightforward. When the primary earner delays his benefit, he effectively purchases a second-to-die annuity. That is, he sacrifices his benefits today in exchange for higher future benefits not only over his own lifetime, but also over the lifetime of the secondary earner if she is widowed.7 The value of this second-to-die annuity increases as the age difference between the primary and secondary earners increases, as this age difference increases the length of time to the second death (the expected payout period for the annuity).

The counterintuitive result in Table 3 comes from the availability of the spousal benefit claiming option. When there is a seven-year age difference between the spouses, the primary earner cannot claim the spousal benefit until he is 69 (and the secondary earner is 62), giving him only one year of spousal benefits before switching to his own benefit. With a two-year age difference, however, the primary earner can claim the spousal benefit at age 66, giving him four years of spousal benefits before switching to his own benefit.

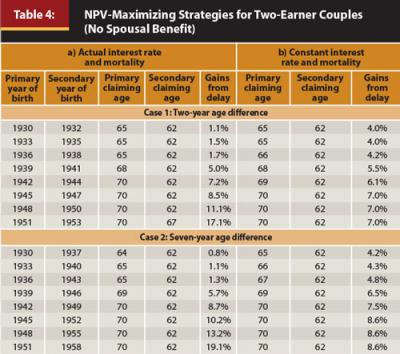

Table 4 presents results for two-earner couples without allowing the spousal benefit claiming option. In panel (a), the actual interest rate and mortality faced by the stylized couples was used; in panel (b), the real interest rate was held constant at 2.9 percent and the mortality profile of the 1951 and 1953 cohorts (top panel) or the 1951 and 1958 cohorts (bottom panel) were used.

Removing the spousal benefit claiming option substantially lowers the gains from delay, particularly in situations where other factors such as the delayed retirement credit and mortality improvements make it more attractive to delay the primary earner’s benefit. This result is again consistent with Munnell et al. (2012), who found that the spousal benefit claiming option produced gains for 83 percent of couples in their sample, and that the gains ranged from 2.6 to 3.1 percent of lifetime benefits. As the previous discussion suggests, without the spousal benefit claiming option, a larger age difference does indeed result in a greater gain from delay.

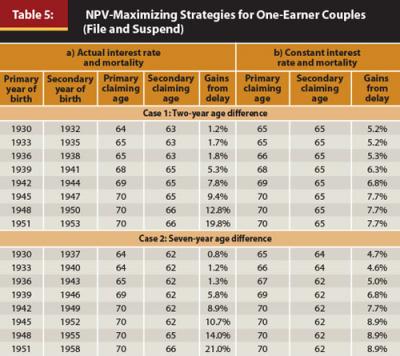

Table 5 deals with one-earner couples. Panel (a) of Table 5 shows that, under the actual interest rate and mortality conditions facing the stylized couples, the gains from delay have greatly increased for one-earner couples.

Panel (b) of Table 5 shows that with the interest rate held constant at 2.9 percent, and assuming the mortality rates of the 1951 and 1953 cohorts (top panel) or the 1951 and 1958 cohorts (bottom panel), the increase in the gains from delay are less dramatic.

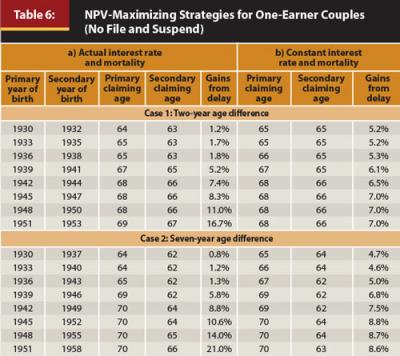

Table 5 assumes the existence of “file and suspend.” The only benefit rule changes reflected in Table 5 include the increase in the delayed retirement credit and the increase in the full retirement age. To determine the effect of “file and suspend,” we recomputed the NPV-maximizing strategies for one-earner couples without this option in Table 6, where panel (a) uses actual interest rates and mortality, while panel (b) holds the interest rate and mortality constant.

Comparing panel (a) of Tables 5 and 6, it is apparent that “file and suspend” makes a modest difference to the gains from delay for more recent cohorts. For earlier cohorts, delaying the primary earner’s benefit beyond full retirement age is not optimal; thus, the unavailability of “file and suspend” does not constrain the secondary earner’s claiming choices. But for more recent cohorts, other factors, including mortality improvements, interest rate changes, and rule changes, make delaying beyond full retirement age attractive. Thus, “file and suspend” provides a boost in the gains from delay by removing a constraint on the secondary earner’s claiming age. These findings are consistent with those of Munnell et al. (2012), who found that couples who benefit from the “file and suspend” option receive relatively modest gains of less than $2,000 on average.

For example, for a couple born in 1951 and 1953, the NPV-maximizing strategy involves the wife claiming a spousal benefit at age 66, while the husband delays to age 70 (see panel (a) of Table 5). Without “file and suspend,” however, the wife would not be able to claim a spousal benefit until she is 68 and her husband is 70. If the wife wishes to claim a spousal benefit at 66 (her full retirement age), the husband would have to claim his own benefit at 67, forgoing some of the gains from delay.

The NPV-maximizing claiming strategy without “file and suspend” represents a compromise; the husband claims his own benefit at age 69, allowing the wife to claim her spousal benefit at 67. This constraint reduces the gains from delay by around 3 percentage points.

The availability of “file and suspend” is less important for couples with a large age difference. For these couples, the wife is so much younger that, even without file and suspend, the husband can delay relatively freely without constraining the wife’s claiming decision. Similar results with a constant interest rate and mortality are clear when comparing panel (b) of Tables 5 and 6. However, “file and suspend” makes a smaller difference to the gains from delay, because delaying the primary earner’s benefit beyond full retirement age is less attractive to begin with.

Consistent with these findings, empirical analysis of data from the Health and Retirement Study (hrsonline.isr.umich.edu), a panel study intended to be representative of older Americans, suggests that individuals born in 1938 and later (those who face more generous terms for delaying Social Security) are more likely to delay claiming. In particular, in the full sample of individuals who were not working immediately before they turned 62, more than 80 percent claimed within a year of turning 62. However, among the subsample born in 1938 or later, only 75.3 percent claimed within a year of turning 62.

Nevertheless, even among this younger group, the vast majority do not appear to delay optimally.8 It is not clear why this is the case. Individuals do appear to be aware of the gains in monthly benefits from delay, and they do not seem to underestimate their life expectancy (Liebman and Luttmer 2011). Another possibility is that most people are hyperbolic discounters (Laibson 1997), who heavily discount the larger future stream of higher benefits relative to receiving benefits today. Delaying Social Security benefits may not be optimal for such discounters.

Conclusion

This analysis has shown that the gains from delaying Social Security have improved dramatically, particularly for couples, since the 1990s. Most of the increase in the gains from delay come from historically low interest rates and improved mortality. However, law changes since the 1990s have also contributed. In particular, the benefit formula has been changed so that delays beyond full retirement age are particularly attractive.

Also, since 2000, one-earner couples have benefited from a provision known as “file and suspend,” which allows the non-earner to claim a spousal benefit even if the primary earner delays his own worker benefit.

Throughout the analysis, we focused on the percent gains from delay relative to claiming at age 62. This measure of the gains from delay does not depend on the individual or primary earner’s PIA. However, it is worth noting the substantial increase in the dollar gains from delay as well. For any of the stylized couples, the gains from delay are less than $5,000 if it is assumed that the primary earner’s PIA is $1,4009 and that he was born in 1930.

In contrast, if the primary earner was born in 1951, a one-earner couple could gain more than $85,000, and a two-earner couple could gain more than $100,000 through optimal claiming relative to claiming at 62. For singles born in 1930 with a PIA of $1,400, the gains from delay are less than $1,000 for women and nonexistent for men. In contrast, for singles born in 1951, the gains from delay are more than $30,000 for men and more than $50,000 for women.10

Endnotes

- Jivan (2004) and Munnell and Sass (2012) showed that, for singles, the effect of interest rate changes and mortality improvements roughly offset each other in the past. Thus, most of the gains for singles have been recent—a result of near-zero interest rates.

- For additional information, see www.ssa.gov/oact/ProgData/ar_drc.html.

- The reduction formula for the widow benefit is complex. A widow who claims at age 60 receives 71.5 percent of the deceased spouse’s PIA plus any delayed retirement credits. If the deceased spouse claimed his or her own worker benefit at full retirement age or later (or died before claiming), the widow benefit is increased linearly until it reaches 100 percent of the deceased spouse’s PIA plus delayed retirement credits at the widow’s full retirement age. If the deceased spouse claimed his or her own worker benefit before full retirement age, the increases in the widow benefit proceed in the same linear fashion but stop when the benefit reaches 82.5 percent of the deceased spouse’s PIA or the deceased spouse’s actual benefit, whichever is higher. For additional details, see Weaver (2002). For details on the full retirement age and actuarial reduction for widow benefits, see www.ssa.gov/survivorplan/survivorchartred.htm.

- All data used in calculating interest rates come from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) available at research.stlouisfed.org/fred2. Nominal 20-year Treasury bonds were not available between 1987 and 1992, so we averaged the rates on nominal 10-year and 30-year Treasury bonds to construct the interest rate for 1992.

- A number of other unusual claiming strategies were ignored. For example, the ability of an individual to claim a benefit, suspend the benefit a few months or years later, then resume the benefit was disallowed. See Kotlikoff (2012) for further discussion of unusual claiming strategies.

- See Shuart, Weaver, and Whitman (2010) for NPV-maximizing widow benefit claiming strategies.

- In contrast, when the secondary spouse delays, she effectively purchases a first-to-die annuity. When she dies, her benefits cease as her spouse continues to receive benefits on his own record. When her spouse dies, her benefits cease because she will be switched to the widow benefit.

- Full details of this empirical analysis are available in Shoven and Slavov (2013b).

- According to the Social Security Administration’s 2012 Annual Statistical Supplement, this is roughly the average PIA for retired workers in December 2011. For more information, see the tables at www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2012/5b.html.

- These calculations assume the actual interest rates and mortality rates that the cohorts faced. In addition, the 1930 primary earner birth cohort is assumed not to have access to “file and suspend,” while the 1951 primary earner birth cohort is assumed to access to this option.

References

Beauchamp, Andrew, and Mathis Wagner. 2013. “Dying to Retire: Adverse Selection and Welfare in Social Security.” Boston College Working Papers in Economics No. 818.

Brown, Jeffrey R., Arie Kapteyn, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011. “Framing Effects and Expected Social Security Claiming Behavior.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 17018.

Coile, Courtney, Peter Diamond, Jonathan Gruber, and Alain Jousten. 2002. “Delays in Claiming Social Security Benefits.” Journal of Public Economics 84 (3): 357–385.

Golub-Sass, Alex, Alicia H. Munnell, and Nadia Karamcheva. 2009. “Strange but True: Claim Social Security Now, Claim More Later.” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Issue in Brief No. 9–9.

Hurd, Michael D., James P. Smith, and Julie M. Zissimopoulos. 2004. “The Effects of Subjective Survival on Retirement and Social Security Claiming.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 19 (6): 761–775.

Jivan, Natalia A. 2004. “How Can the Actuarial Reduction for Social Security Early Retirement be Right?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Just the Facts No. 11.

Kotlikoff, Laurence. 2012. “44 Social Security ‘Secrets’ All Baby Boomers and Millions of Current Recipients Need to Know — Revised!” Forbes July 3.

Laibson, David. 1997. “Golden Eggs and Hyperbolic Discounting.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (2): 443–478.

Liebman, Jeffrey B., and Erzo F.P. Luttmer. 2011. “Would People Behave Differently if they Better Understood Social Security? Evidence from a Field Experiment.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 17287.

Mahaney, James I., and Peter C. Carlson. 2007. “Rethinking Social Security Claiming in 401(k) World.” Pension Research Council Working Paper No. 2007–18.

Meyer, William, and William Reichenstein. 2010. “Social Security: When to Start Benefits and How to Minimize Longevity Risk.” Journal of Financial Planning 23 (3): 49–59.

Munnell, Alicia H., and Steven A. Sass. 2012. “Can the Actuarial Reduction for Social Security Early Retirement Still Be Right?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Issue in Brief No. 12–6.

Munnell, Alicia H., Alex Golub-Sass, and Nadia Karamcheva. 2009. “Strange but True: Claim Social Security Now, Claim More Later.” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Issue in Brief No. 9–9.

Munnell, Alicia H., Alex Golub-Sass, and Nadia Karamcheva. 2012. “Understanding Unusual Social Security Claiming Strategies.” Journal of Financial Planning 26 (8): 40–47.

Munnell, Alicia H., and Mauricio Soto. 2005. “Why do Women Claim Social Security Benefits So Early?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Issue in Brief No. 35.

Sass, Steven A., Wei Sun, and Anthony Webb. 2007. “Why Do Married Men Claim Social Security Benefits So Early? Ignorance or Caddishness?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College Working Paper No. 2007–17.

Sass, Steven A., Wei Sun, and Anthony Webb. 2013. “Social Security Claiming Decision of Married Men and Widow Poverty.” Economic Letters 119 (1): 20–23.

Shoven, John B., and Sita Nataraj Slavov. 2013a. “Does It Pay to Delay Social Security?” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance October 22 .

Shoven, John B., and Sita Nataraj Slavov. 2013b. “Recent Changes in the Gains from Delaying Social Security.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 19370. www.nber.org/papers/w19370.

Shuart, Amy N., David A. Weaver, and Kevin Whitman. 2010. “Widowed Before Retirement: Social Security Benefit Claiming Strategies.” Journal of Financial Planning 23 (4): 45–53.

Sun, Wei, and Anthony Webb. 2009. “How Much Do Households Really Lose by Claiming Social Security at Age 62?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College Working Paper No. 2009–11.

Weaver, David A. 2002. “The Widow(er)’s Limit Provision of Social Security.” Social Security Bulletin 64 (1): 1-15.

Citation

Shoven, John B., and Sita Nataraj Slavov. 2014. “Recent Changes in the Gains from Delaying Social Security.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (3): 32–41.