Journal of Financial Planning: March 2018

Julie A. Welch, CPA, PFS, CFP®, is the director of tax services and a shareholder with Meara Welch Browne P.C. in Leawood, Kansas.

Randy Gardner, J.D., LL.M., CPA, CFP®, is founder of Goals Gap Planning LLC

(goalsgapplanning.com), a fee-only personal financial planning firm.

The tax cuts and Jobs Act (the act) includes provisions financial planners need to know to run their businesses and possibly pass on to their business clients. This column addresses some of those provisions, including the new 20 percent of qualified business income deduction; the flat 21 percent tax on corporate income and its impact on choice of entity for operating a business; the resurrected tax breaks for acquiring assets; and the new hurdle for deducting business losses.

Qualified Business Income Deduction

One of the most complex provisions in the act is a 20 percent deduction for individuals related to qualified business income (QBI), including business income from self-employment and other pass-through businesses. You may hear this referred to as the Section 199A deduction, referring to the Internal Revenue Code section that allows this deduction. Since the corporate rate was reduced to 21 percent, this 20 percent deduction provision was enacted to give individuals with qualifying business income—including sole proprietors, owners of limited liability companies, partners in partnerships, owners of S corporations, trusts, and estates—a tax break as well. While the flat 21 percent corporate rate was made permanent in the tax law, this 20 percent deduction starts in 2018 and ends in 2025.

There are many unanswered questions about what qualifies as business income and who is entitled to the deduction—questions that will likely be addressed in forthcoming guidance from the IRS. What we do know is: taxpayers with taxable income (before claiming this new QBI deduction) of less than $315,000 for married couples filing jointly ($157,500 for other filers) will get a 20 percent deduction, creating a significant tax savings.

How is the 20 percent deduction calculated? First, you must determine your QBI. Second, you must determine what to multiply the 20 percent by to arrive at the deduction amount. Third, you must consider rules for higher-income taxpayers that could reduce or eliminate the deduction amount.

QBI is your allocable share of trade or business income (revenue less deductions). It excludes investment income, such as capital gains and losses, dividends, and nonbusiness interest income, and it also excludes reasonable compensation paid to the person and guaranteed payments from partnerships.

To arrive at the deduction amount (before the limitation for higher-income taxpayers), 20 percent is multiplied by the lesser of: (1) QBI; or (2) the taxpayer’s taxable income (before the 20 percent deduction), less any net capital gain.

Next, consider the limitations for higher-income taxpayers. For those taxpayers with taxable income above the $315,000 for those married filing jointly ($157,500 for other filers), determine if the QBI relates to specified service businesses because the 20 percent deduction phases out for these businesses. These businesses deliver services in the fields of health, law, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, brokerage services, or any business where the principal asset is the reputation or skill of its employees or owners, or which involves the performance of services that consist of investing and investment management trading, or dealing in securities, partnership interests, or commodities. This definition clearly includes financial planners. Architects and engineers are specifically not included which, for this deduction, is favorable because a deduction may still be available if they have income in excess of the phase-out ranges.

Example 1: Don is a single CPA doing business as an S corporation. He has QBI of $60,000 from the accounting practice after payment of a reasonable salary and taxable income of $130,000 ($90,000 salary plus $60,000 pass through income less itemized deductions of $20,000). Because Don is not a higher-income taxpayer, his 20 percent deduction is $12,000 ($60,000 x 20 percent), reducing his taxable income to $118,000 ($130,000 – $12,000) and lowering his tax by $4,800 ($12,000 deduction times his 24 percent marginal tax rate). It is irrelevant that Don is in a service business. If Don was a non-service business, such as a widget manufacturer, the outcome would be the same.

The phase-out range for the QBI deduction is $315,000 to $415,000 for those married filing jointly and $157,500 to $207,500 for other filers. A complex computation determines the amount of the 20 percent deduction that is allowed in this phase-out range. Once the top of the range is exceeded, however, there is no deduction for those in the service fields, but the deduction may still be allowed for non-service businesses.

Example 2: Lindsey is a financial planner doing business in an S corporation with QBI of $100,000 after payment of a reasonable salary and taxable income of $500,000. Since Lindsey is a higher-income taxpayer in a service business, she is ineligible for the 20 percent deduction and thus receives no deduction.

For those not in the service fields, if taxable income exceeds $415,000 for married filing jointly filers ($207,500 for other filers), the 20 percent deduction for QBI is still possible, but it cannot exceed the greater of: (1) W-2 wages x 50 percent; or (2) W-2 wages x 25 percent plus 2.5 percent of the unadjusted basis of tangible depreciable property used in the business.

In other words, if there are no W-2 wages, then the deduction is limited to 2.5 percent of the unadjusted basis of tangible depreciable property used in the business. Although we are not going into the details here, there are rules to follow when calculating the unadjusted basis of tangible depreciation property.

Example 3: Jimmy owns 20 percent of an S corporation that manufactures toys and he works full-time for the corporation. W-2 wages paid to the employees of the S corporation are $500,000, and Jimmy’s allocable share is $100,000. The corporation earns $2 million, and Jimmy’s allocable share is $400,000. The adjusted basis of the assets is $200,000, and Jimmy’s allocable share is $40,000. His taxable income is $700,000. His 20 percent deduction would be $80,000 ($400,000 x 20 percent).

However, because Jimmy is a higher-income taxpayer, his deduction is limited to the greater of $50,000 ($100,000 of wages times 50 percent) or $26,000 ($100,000 of wages times 25 percent plus 2.5 percent of adjusted basis x $40,000). Therefore, Jimmy’s deduction is actually $50,000, reducing his taxable income from $700,000 to $650,000 and reducing his tax by $18,500 ($50,000 deduction times his 37 percent marginal tax rate).

Because of this deduction, expect some trends and tax strategies to emerge, including:

The new deduction may be the impetus employees need to leave the security and fringe benefits of the workplace and start their own businesses.

Workers will design arrangements with their employers to be treated as independent contractors rather than as employees.

Businesses will separate their service and non-service operations into separate entities.

Individuals with income in or near the phase-out ranges will look for businesses or make acquisitions that will reduce their income below the phase-out range.

Higher-income taxpayers may benefit from investing in REITs, master limited partnerships, and employee- and/or capital-intensive businesses.

Choice of Entity Factors

The tax rate for C corporations is reduced to a flat 21 percent. Although this reduction is especially beneficial to high-income, large C corporations, the income of closely held C corporations is still subject to double taxation: 21 percent at the corporate level plus 0 percent, 15 percent, 18.8 percent, or 23.8 percent at the individual level when a dividend is paid. In contrast, the 20 percent QBI deduction makes the maximum federal tax rate 29.6 percent (37 percent x 80 percent) for pass-through income from entities, such as partnerships, S corporations, and trusts.

Considering only marginal tax rates, flow-through entities appear to offer an advantage. In the end, however, businesses will have to think through the factors that have historically controlled choice of entity decisions, such as: the availability of fringe benefits and retirement plans; payroll taxes for the owners; limited liability and asset protection; the ease of obtaining financing and entity rules with regard to debt; the deductibility of start-up losses on the owner’s individual tax return; the projected earnings of the business over its life cycle from formation to sale or dissolution; and state compliance formalities.

With the elimination of many deductions for individuals, tax-free fringe benefit planning may emerge as a more important factor. Forming a corporation is as easy as filing with the state and transferring assets (possibly from the current pass-through entity) to a corporation in exchange for stock. If you have an S corporation, you could revoke your election or intentionally fail the S election requirements, but you will need to wait five years if you want to be treated as an S corporation again.

Asset Acquisition Enhancements

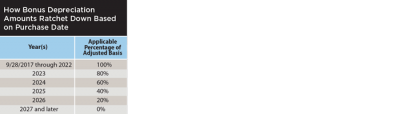

Bonus depreciation. The act expands the definition of “qualified property” to include used property and increases the bonus depreciation from 50 percent to 100 percent for purchases made after Sept. 28, 2017 through 2022. After that date, the bonus depreciation amount is ratcheted down as shown in the table above.

Listed property. The depreciation limitations for listed property (such as automobiles) were adjusted in two ways. First, when bonus depreciation is not used, the depreciation allowed is as follows: $10,000 in the first year, $16,000 in the second year, $9,600 in the third year, and $5,760 in the fourth and subsequent years. Second, the act removes computers and peripheral equipment from the definition of listed property, relieving taxpayers of the additional record-keeping requirements for listed property.

Section 179 immediate expensing. Under the act, the annual expensing cap is raised to $1 million with the phase-out beginning at $2.5 million of qualifying purchases (indexed for inflation). The definition of eligible property is expanded to include tangible personal property used predominantly to furnish lodging and the following improvements to nonresidential real property: roofs; heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning; fire protection and alarm systems; and security systems.

In short, the act makes it possible to immediately recover the cost of assets acquired for your business (cars, computers, equipment, and more). If you or a client is building a new building or improving a leasehold, it may be a good idea to perform a cost segregation study to optimize deductions. If you need to add a new roof or add climate-control and safety improvements to your commercial buildings, you may be able to immediately expense the improvements.

Keep in mind, however, that immediate depreciation deductions are not always the best option. The deductions may reduce your QBI deduction; and it may be better to defer depreciation deductions to future years when your business income and tax rate may be higher. In some situations, it is better to use Section 179 rather than bonus depreciation, and vice versa—something you’ll want to discuss with your tax adviser.

Excess Business Losses and Net Operating Losses

Under prior law, losses for non-corporate taxpayers were subject to three limitations: (1) the taxpayer’s basis in the entity limitation; (2) the at-risk rules; and (3) the passive loss rules. The act adds a fourth limitation on “excess business losses” of individuals, partnerships, and S corporations. An excess business loss for the taxable year is disallowed and treated as a net operating loss (NOL) carryover to the next taxable year.

Excess business loss is defined as the amount by which the taxpayer’s aggregate deductions attributable to all trades or businesses exceeds the sum of the taxpayer’s aggregate gross income attributable to all such trades or businesses plus $250,000 ($500,000 in the case of joint filers). Each of these dollar amounts will be adjusted for inflation. If the aggregate losses are less than these amounts, the new rules do not apply and the loss is allowed to be deducted against other income in the taxable year.

Furthermore, the act suspends, until 2026, the two-year carryback of NOLs except in the case of certain disaster losses incurred in the trade or business of farming, or by certain small businesses. As a result, individuals and businesses with NOLs will generally be prohibited from carrying the loss back to prior years and obtaining refunds.

The new law also limits the annual NOL deduction to 80 percent of taxable income (determined without regard to the deduction). Carryovers to other years are adjusted to take account of this limitation and may be carried forward indefinitely. In other words, NOLs may take longer to use, but they will no longer expire.

Miscellaneous Provisions

The following are additional provisions that may affect planners and their business-owner clients:

Deductions for entertainment, amusement, and recreation—even if directly related to the conduct of a taxpayer’s trade or business—are repealed.

Deductions for “free food” are limited by reducing the deductible amount paid for most employee meals to 50 percent until 2026 when the deduction is totally eliminated.

A tax credit in 2018 and 2019 is added for certain employers who provide family and medical leave under a written policy.

Net interest deductions are limited to 30 percent of adjusted taxable income with a carryforward for denied deductions. This provision applies to all business entity types, but only those with more than $25 million of gross receipts.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act offers significant tax breaks to business owners and entrepreneurs. Although most of these changes will expire in 2026, you should talk to your tax adviser, and encourage your clients to talk to their advisers, about whether now is the time to switch from one entity to another and whether other changes to the business landscape warrant a change to your business practices.

Julie Welch and Randy Gardner are coauthors of the recently updated 101 Tax Saving Ideas, 11th edition. To obtain a copy, email Julie HERE.