Journal of Financial Planning: May 2011

David M. Cordell, Ph.D., CFA, CFP®, CLU, is director of finance programs at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Thomas P. Langdon, J.D., CFP®, CFA, is professor of business law at Roger Williams University in Bristol, Rhode Island.

At some point in every kid’s life, his or her mother offers this wise advice: if life gives you lemons, make lemonade. Of course, mothers never mention that you have to add some sugar or the lemonade will taste no better than the lemons.

Many of us feel that the U.S. government has not simply been giving us lemons, it has been throwing them at us. To paraphrase the old lady in the Wendy’s commercial a couple of decades ago, “Where’s the sugar?”

Well, if Mom were around, and if she knew something about financial planning, she might just say that the sugar is life insurance.

Washington, D.C.: Land of Cherry Blossoms (and Lemons)

The last several months have been both exciting and scary for those following the national and state budget and tax debates. After a November election that upset the reigning power base in Washington, there was renewed hope for bi-partisan compromise that would move the country forward. Feeling the backlash from the election, politicians in Washington entered into a compromise on tax-policy initiatives that were passed just a few weeks before the close of the year.

Negotiations that led up to the enactment of the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 appeared to demonstrate a willingness on both sides of the political spectrum to give up some of their demands so that a workable solution for taxpayers could be achieved. The changes resulting from last fall’s election and the apparent renewed emphasis of policymakers to abandon partisan dogma in favor of reasonable compromise were perceived by many to be a refreshing change in Washington.

How long will this new sense of stewardship last? Apparently, not too long. As we write this article, both sides of the political aisle have retreated to their pre-election dogma and are embroiled in discussions that include threats of shutting down the national government.

Taxpayer Uncertainty

Even if Washington averts a shutdown this time, it appears the stage is being set for another showdown on tax policy when many of the provisions in the Bush tax cuts, which were extended for two years by last December’s legislation, expire at the end of 2012. It appears that the perfect storm is again brewing in Washington, and an age-old economic adage should be revised from “let the buyer beware” to “let the taxpayer beware.”

Since 2001, with the enactment of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (EGTRRA), lawmakers have moved away from a concept of “tax policy” to a system of creating temporary changes to tax rules that are designed, in many cases, to achieve political as opposed to policy ends. Imposing expiration dates on these changes allows lawmakers to manipulate federal revenues to meet budget cycle requirements, but results in a great degree of uncertainty for taxpayers. Greater uncertainty means greater risk. To the extent that more taxpayers refrain from or put off tax planning due to the greater perceived risks from taking the wrong action, the government stands to benefit. This is particularly true in an era of rising tax rates, which we seem to be entering at both the state and federal levels of government.

When lawmakers refuse to work together and instead pursue purely partisan objectives, taxpayer risk increases. One thing does seem certain given the mounting federal debt—income tax rates will have to increase in the future because it is unlikely that spending cuts will be enough to cover the size of the ever-increasing national debt. If Congress and the president do nothing, income tax rates will increase in 2013 when the Bush tax cuts expire. Similar circumstances face many state governments as well.

Estate Taxation Uncertainty

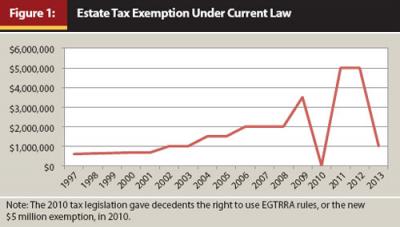

While the impact of temporary tax measures increases taxpayer risk for income tax planning, that risk is even more pronounced for longer-term estate planning. Traditionally, the amount of wealth that could be transferred tax-free at death (under federal law) was fixed, permitting taxpayers to plan for transfers that avoided the tax or encouraging them to generate sources of funding to cover the tax liability. Because of temporary changes in tax law, the amount exempt from federal estate tax has varied over time (see Figure 1). Under current law, a taxpayer can transfer $5 million without triggering a federal gift or estate tax. The $5 million exemption expires December 31, 2012, and reverts to its 2001 level of $1 million (as indexed by the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997) unless Congress acts. The president’s fiscal year 2012 budget proposes to reduce the exemption to $3.5 million.

What will the exemption be after 2012? It will depend on the willingness of policymakers to compromise on a major tax-policy issue in a presidential election year. With that backdrop, the answer is that nobody knows what will happen to the estate tax exemption.

Business as usual in Washington over the past decade or so has resulted in an expansion of the definition of political risk from an investor/taxpayer perspective. Originally, political risk implied the risk of investing in foreign countries with unstable governments that had a propensity to confiscate assets when times got bad, resulting in a loss of capital for investors. That offshore risk has now moved onshore in part because of the temporary tax-policy changes that have become commonplace in our nation’s capital. Elections, not policy, now seem to determine whether taxes will go up or spending will go down. The lost art of compromise, despite a brief resurgence in December 2010, may be lost again as candidates begin posturing for the 2012 elections.

Hedging Tax Uncertainty

Instead of allowing these events to paralyze their ability to make decisions, taxpayers need to take action to protect themselves and reduce their exposure to the uncertainties raised by fluctuating tax and spending policies in Washington and in state capitols across the country. In light of the potential for increasing tax rates at both the state and federal levels, taxpayers should consider tax-diversifying their portfolios.

Diversification of investment portfolios is a commonly accepted practice among practitioners and clients alike due to its advantage of reducing risk without sacrificing return. Until recently, however, diversification of the tax consequence of portfolios has been largely ignored. Many individuals have a significant portion of their savings in tax-deferred accounts. Financial advisors, accountants, and the popular media have touted the benefits of contributing to 401(k)s, 403(b)s, and IRAs for decades. These vehicles allow taxpayers to receive current tax deductions while shifting income into future tax periods.

Tax deferral works best, however, when taxpayers withdraw money from accounts in a period when they will experience a lower tax rate than they would have paid in the deferral period. Given current circumstances, this outcome may not be likely for many people. Taxpayers who invest all of their assets in tax-deferred vehicles are at the mercy of their federal and state legislatures, and as tax rates begin to rise, the after-tax return on their portfolios will decrease.

Having some assets in tax-deferred, non-qualified, and tax-free accounts will allow a taxpayer to make adjustments to his or her portfolio to minimize the impact of tax changes. For example, an individual with tax-free accounts could withdraw enough money from those accounts every year so that withdrawals from tax-deferred accounts will not be subject to higher marginal income tax rates. If all of one’s assets reside in one type of account (tax-deferred, non-qualified, or tax-free), the ability to respond to tax-law changes is reduced, limiting the taxpayer’s planning flexibility.

Opportunities for tax-free investing are relatively rare. Roth IRAs, Roth 401(k)s, and Roth 403(b)s permit taxpayers to choose tax-free growth in lieu of tax deferral. If income tax rates increase in the future, assets inside a Roth account will be immune from those tax hikes, thereby increasing the after-tax rate of return for the investor. Roth accumulations, however, are subject to estate tax upon the death of the account owner. How much of the Roth account will be subject to tax? That depends on the willingness of policymakers to compromise on an exemption before the end of 2012.

Life Insurance: The Perfect Sweetener

Life insurance may be an ideal asset to hold as a hedge against the risks associated with tax-rate changes. Life insurance cash value accumulations are exempt from income tax, the death benefit is generally income tax free, and, if the policy is owned by a trust, the death benefit may also be exempt from estate tax. Sophisticated life insurance trust planning techniques allow the policy death benefit to be excluded from the estate while giving lifetime benefits in the policy to the taxpayer’s family. When properly structured, life insurance can ensure that wealth will be transferred to beneficiaries regardless of the estate tax exemption limits set by Congress, removing both income tax and estate tax risk for the taxpayer.

It’s easy to see how life insurance is a hedge against the risk of early death and replaces human capital lost before the financial benefits of that capital are fully realized. Life insurance may also be considered a hedge against the potential for future tax increases and the uncertainty surrounding both tax rates and gift and estate tax exemptions. Life insurance should be considered and proposed as an important asset in the taxpayer’s arsenal to hedge against traditional mortality risks and to create a pool of funds buffered from the whims of political action or inaction in Washington.

Or, to put it another way: a spoonful of life insurance may be exactly what is needed to counteract those Washington lemons.