Journal of Financial Planning: May 2011

Wade D. Pfau, Ph.D., an associate professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo, Japan, holds a doctorate in economics from Princeton University. His hometown is Des Moines, Iowa. He can be reached at wpfau@grips.ac.jp.

[FROM THE MAY 2011 JOURNAL]

Executive Summary

- Focusing on a “safe withdrawal rate” and then deriving a “wealth accumulation target” to achieve by the retirement date may not be the best way to approach retirement planning. Such a formulation isolates the working (accumulation) and retirement (decumulation) phases.

- When considered together, the lowest sustainable withdrawal rates (which give us our idea of the safe withdrawal rate) tend to follow prolonged bull markets, while the highest sustainable withdrawal rates tend to follow prolonged bear markets.

- The focus of retirement planning should be on the savings rate rather than the withdrawal rate. The “safe savings rate” may be based on historical simulations as the savings rate that proves sufficient to support the desired retirement expenditures from a life-cycle perspective, including both the accumulation and decumulation phases. Safe savings rates derived in this manner are less volatile than withdrawal rates and imply a lower ex-post cost to being overly conservative.

- Unlike the 4 percent rule for a safe withdrawal rate, there is not a universal “safe savings rate,” but guidelines can be created. Starting to save early and consistently for retirement at a reasonable savings rate will provide the best chance to meet retirement expenditure goals. Actual withdrawal rates and wealth accumulations at retirement may be treated as almost an afterthought in this framework. But the savings plan should be adhered to regardless of whether it seems one is accumulating either more or less wealth than is needed based on traditional criteria.

Acknowledgments: I am grateful for excellent comments and insights received from this Journal’s anonymous reviewers, Rob Bennett, Bogleheads Forum users (particularly CaliJim, grayfox, grberry, magellan, Majormajor78, and SpecialK22), Nanette Byrnes, Dan Moisand, Jennie L. Phipps, Mike Piper (and Larry, who made comments at his blog), Dick Purcell, Felix Salmon (as well as his blog’s comments from dWj, ErnieD, and TFF), and Bob Veres. The author is also grateful for financial support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) #20730179.

Using 65 years of data between 1926 and 1991, Bengen (1994) famously motivated the 4 percent withdrawal rule. Bengen (2006) later coined the term “SAFEMAX” to describe the maximum withdrawal rate, as a percentage of the account balance at the retirement date, which could be adjusted for inflation in each subsequent year and would allow for at least 30 years of withdrawals without exhausting one’s savings during all of the rolling periods available in the historical data. More simply, the SAFEMAX is the maximum sustainable withdrawal rate (MWR) from the worst-case retirement year. Rightfully so, Bengen’s study demonstrated how volatility in asset returns causes the “safe withdrawal rate” to fall below the withdrawal rate possible with assumed constant asset returns matching historical averages. His study spurred the development of a cottage industry with numerous researchers investigating how retirees might safely increase their withdrawal rate. Such studies have overwhelmingly investigated retirement in isolation from the working phase that preceded it.

The Journal of Financial Planning published William Bengen’s landmark study 17 years ago, setting into place an initial condition that influenced so much subsequent research. But I wonder how different our ideas about retirement planning might be if Bengen had chanced upon a longer time series of historical data when he formulated his study. With more data, he might have decided to consider historical simulations that included both the working (accumulation) and retirement (decumulation) phases in one integrated whole. When considered as a whole, the historical data show that, though the relationship is not perfect, the lowest MWRs (which give us our conception of the safe withdrawal rate) tend to occur after prolonged bull markets. Prolonged bear markets during the accumulation phase tend to allow for much larger MWRs. This tendency motivates a fundamental rethinking of retirement planning, as worrying about the “safe withdrawal rate” and a “wealth accumulation target” is distracting and potentially harmful for those engaged in the retirement planning process.

Rather, it may be better to think in terms of a “safe savings rate” that has demonstrated success in financing desired retirement expenditures for overlapping historical periods including both the accumulation and decumulation phases. Put another way, someone saving at her “safe savings rate” will likely be able to finance her intended expenditures regardless of her actual wealth accumulation and withdrawal rate. As an added feature, the volatility of past life-cycle-based minimum necessary savings rates (LMSRs) is less than that of MWRs; they range between 9.3 percent and 16.6 percent of salary over the historical period for our stylized baseline individual.

I am suggesting that the following retirement planning process, which isolates the accumulation and decumulation phases, is not appropriate:

Step 1: Estimate the withdrawals needed from financial assets to pay for planned retirement expenses after accounting for Social Security, any defined-pension benefits, and any other income sources. Define these planned retirement expenses as a replacement rate (RR) from pre-retirement salary.

Step 2: Decide on a withdrawal rate (WR) you feel comfortable using based on what has been shown sufficiently capable by the historical data.

Step 3: Determine the wealth accumulation (W) you wish to achieve by retirement, defined as W = RR / WR.

Step 4: Determine the savings rate you need during your working years to achieve this wealth accumulation goal.

I suggest as a replacement the following retirement planning process:

Step 1: This step is the same as above.

Step 2: Decide on a savings rate you feel comfortable using based on what has been shown sufficiently capable of financing your desired retirement expenditures by the historical data.

If one saves responsibly throughout her career, she will likely be able to finance her intended expenditures regardless of what withdrawal rate from her savings this implies. Of course, a caveat must be included that the “safe savings rate” is merely what has been shown to work in rolling periods from the historical data. The same caveat applies to the “safe withdrawal rate”—in the future we might experience a situation in which the safe savings rate must be revised upward or the safe withdrawal rate downward. It must also be clear that the findings about safe savings rates in this study are not one-size-fits-all. The study merely illustrates the principles at work by focusing on the case of a particular stylized individual. Real people will vary in their income and savings patterns, consumption smoothing needs, desired retirement expenditures, and asset allocation choices. This leaves an important role for financial planners to assist their clients in determining the “safe savings rate” that fits the client’s particular life circumstances. This paper provides a framework to accomplish this task.

Methodology and Data

I use a historical simulations approach, considering the perspective of individuals retiring in each year of the historical period. In the baseline case, an individual saves for retirement during the final 30 years of her career, and she earns a constant real income in each of these years. A fixed savings rate determines the fraction of this income she saves at the end of each of the 30 years. Savings are deposited into an investment portfolio that is allocated 60 percent into large-capitalization stocks (Standard & Poor’s Composite Stock Price Index) and 40 percent into short-term fixed-income assets (annual yield from six-month commercial paper rates). The investment portfolio is rebalanced to the targeted asset allocation at the end of each year.

In the baseline case, retirement begins at the start of the 31st year, and the retirement period is assumed to last for 30 years. The accumulation and decumulation life cycle is 60 years. Withdrawals are made at the beginning of each year during retirement. The underlying 60/40 asset allocation remains the same during retirement, as does the annual rebalancing assumption. Withdrawal amounts are defined as a replacement rate from final pre-retirement salary. I assume that the baseline individual wishes to replace 50 percent of her final salary with withdrawals from her accumulated wealth. This 50 percent is more than it may initially sound, as it is only the part from retirement savings. Social Security benefits and any other income sources would be added on top of this. In addition, after retiring, one no longer has to save for retirement or contribute to Social Security, which increases the replacement rate with respect to what could have been spent before retirement. Withdrawal amounts are then adjusted each year for the previous year’s inflation. Portfolio administrative and planning fees are not charged, and I do not attempt to account for taxes. A particular savings rate was successful if it provided enough wealth at retirement to sustain 30 years of withdrawals without having the account balance fall below zero. Actual wealth accumulations and withdrawal rates may vary substantially for different retirees.

The data for annual financial asset returns between 1871 and 2009 are from Robert Shiller’s website (www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.htm). With these 139 years of data, I consider 30-year careers are followed by retirements beginning in the years 1901 to 2010. In addition, I consider 30-year retirements beginning between 1871 and 1980. In considering a 60-year life cycle with 30 years of work followed by 30 years of retirement, there are 80 overlapping periods with retirements beginning between 1901 and 1980.?

Safe Withdrawal Rates

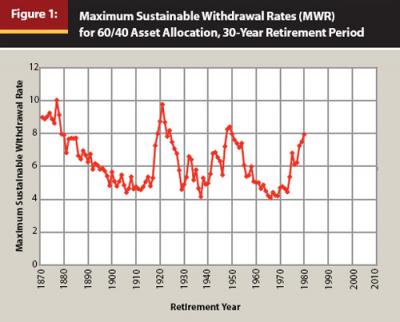

Figure 1 shows the historical maximum sustainable withdrawal rates (MWRs) for 30 years of inflation-adjusted withdrawals with a 60/40 asset allocation. MWRs have historically exhibited significant volatility. The 1877 retiree enjoyed the highest MWR in history (10.04 percent), but by 1906 the MWR had fallen to 4.41 percent. It rose again to 9.78 percent in 1921, and then declined to 4.59 percent in 1929. After further gyrations, it fell to 4.15 percent in 1937, and then rose to 8.42 percent in 1949. Another precipitous decline followed, and the SAFEMAX value (the lowest MWR in history) of 4.08 percent was experienced by the 1966 retiree. By 1980, the MWR had risen again to 7.95 percent.

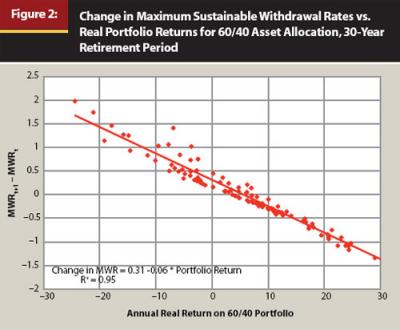

Regarding the volatility of MWRs, Figure 2 shows a very close relationship in which the MWR tends to fall after a year with high real portfolio returns and rises after negative returns. The figure plots annual real returns on a 60/40 portfolio against the percentage point change to the MWR for a new retiree in the next year. The fitted regression line shows that on average, the MWR falls in years that real portfolio returns exceed 5.6 percent.

Minimum Necessary Savings Rate to Achieve a Fixed Wealth Accumulation Goal

The next step in developing this article’s thesis is to briefly consider turning Bengen’s SAFEMAX calculation on its head and to calculate a safe savings rate in isolation from the following retirement period. I calculate the minimum necessary fixed savings rate required over a 30-year career to achieve a wealth accumulation target at the retirement date. I consider a person wishing to replace 50 percent of her final salary with withdrawals from her accumulated wealth. She wishes to play it safe and hopes to save enough so that her desired expenditures represent a 4 percent withdrawal rate from her accumulated wealth. Therefore, she must accumulate wealth that is 12.5 (= 50 / 4) times her final salary. This is the approach of traditional retirement planning.

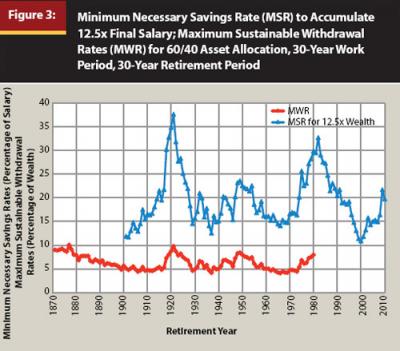

Figure 3 shows the path of minimum necessary savings rates (MSRs) for 30-year careers to achieve the fixed wealth accumulation goal. These MSRs are volatile and can be quite high. The necessary fixed savings rates over 30 years exceeded 20 percent in 42 of the 110 post-career retirement years. They were over 30 percent for new retirees between 1918 and 1922 and in 1982. But important to note is how the pattern of these MSRs closely follows that of the corresponding MWRs for each retirement year. For instance, the largest MSR of 37.7 percent occurs for someone retiring in 1921, but that is also the year that allows for the largest MWR of 9.78 percent during the period in which data for both series are available. As well, retirement years that experienced relative lows for MWRs also experienced relative lows for MSRs. The MSR for 1929 was 14.5 percent, for 1937 was 12.6 percent, and for 1966 was 14.1 percent. These retirement years experienced MWRs of 4.59 percent, 4.15 percent, and 4.08 percent, respectively. More recently, the 2000 retiree enjoyed the lowest MSR in history. This individual only needed to save a fixed 10.89 percent of her annual salary over a 30-year career to be able to retire with accumulated wealth equal to 12.5 times her final salary. We will not know the corresponding MWR for the 2000 retiree until the end of 2029.

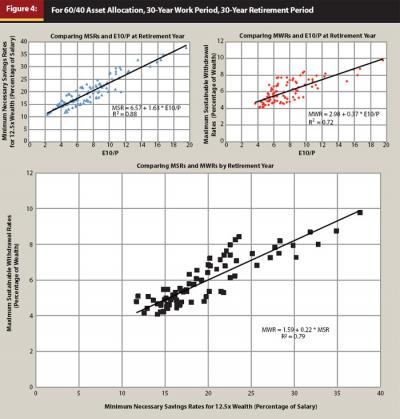

The relationship between MSRs and MWRs is further illustrated in Figure 4, which shows that the variation in MWRs that can be explained by MSRs is 79 percent. This figure also shows that the link between MSRs and MWRs is the market valuation level at the retirement date. Market valuations are represented by the 10-year average of real earnings divided by the real stock market index value at the beginning of the retirement year (E10/P). When this smoothed earnings yield is low, the stock market tends to be overvalued as a result of a recent run-up in stock prices. Stock price appreciation helps the worker reach her wealth accumulation goal with a lower savings rate. At the same time, an overvalued stock market at the retirement date, as represented by the low smoothed earnings yield, is also correlated with a lower subsequent MWR for the new retiree. Because the observations for this figure are from overlapping periods, formally determining the statistical significance of these relationships is a complex issue. This article proceeds under the assumption that the relationships seen in Figure 4 are meaningful and can be expected to continue in the future.

An Integrated Life-Cycle Approach for Savings and Withdrawals

Now we are ready to integrate the working and retirement phases to determine the savings rate needed to finance the planned retirement expenditures for rolling 60-year periods from the data. The baseline individual wishes to withdraw an inflation-adjusted 50 percent of her final salary from her investment portfolio at the beginning of each year for 30 years. Prior to retiring, she earns a constant real salary over 30 years, and her objective is to determine the minimum necessary savings rate to be able to finance her desired retirement expenditures. Her asset allocation during the entire 60-year period is 60/40 for stocks and short-term fixed-income assets.

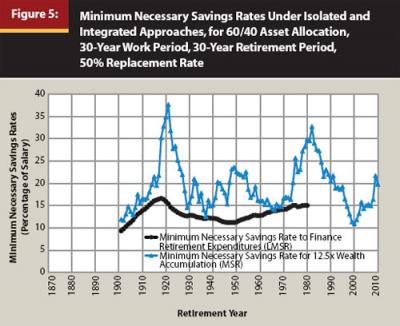

Figure 5 provides these results, showing both the savings rate needed to accumulate 12.5 times final salary (this is the MSR described in the previous section) and the life-cycle-based minimum savings rate needed to finance desired expenditures (LMSR). The LMSR curve is the main contribution of this paper, as it shows from rolling historical periods the minimum necessary savings rate for the accumulation phase to pay for the desired retirement expenditures. In the context of Bengen’s original study, the maximum value of the LMSR curve—16.62 percent in 1918—becomes the SAFEMIN savings rate from a lifetime perspective that corresponds to Bengen’s SAFEMAX withdrawal rate. Had the baseline individual used a fixed 16.62 percent savings rate, she would have always saved enough to finance her desired retirement expenses, having barely accomplished this in the worst-case retirement year of 1918.

Retirement planning in the context of the LMSR curve is less prone to making large sacrifices in order to follow a conservative strategy. In the context of safe withdrawal rates, if someone used a 4 percent withdrawal rate at a time that would have supported an 8 percent withdrawal rate, she is sacrificing 50 percent of the spending power from her savings (her overall spending reduction would be less after including Social Security and other income sources). But in the context of safe savings rates, if someone saved at a rate of 16.62 percent at a time when she only needed to save 9.34 percent (this is the lowest LMSR value, occurring for the 1901 retiree), she is sacrificing only a little over 7 percent of her annual salary as surplus savings. She will usually also find that she still has funds remaining after a 30-year retirement period, but she was indeed able to afford her desired expenditures. In the period since 1926, which is used in most withdrawal rate studies, the range of LMSR values is even narrower. The lowest LMSR value was 11.2 percent for retirees between 1946 and 1949, while the highest LMSR value (the SAFEMIN from the limited sample) is 15.1 percent for the 1975 and 1979 retiree.

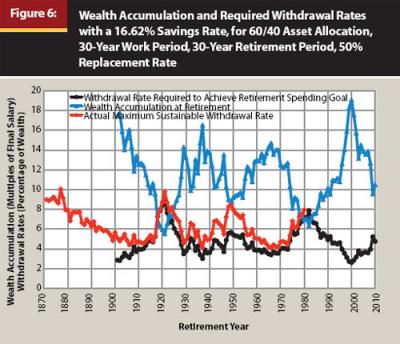

To provide further intuition for these findings, Figure 6 shows what would have happened for our stylized individual who saved with a fixed 16.62 percent savings rate in each rolling historical period. With a 16.62 percent savings rate, the wealth accumulation at retirement varies dramatically over time. The lowest wealth accumulation was 5.52 times final salary for the 1921 retiree, while the highest wealth accumulation was 19.07 times final salary for the 2000 retiree. For that unfortunate 1921 retiree, the low wealth accumulation implies a required withdrawal rate of 9.06 percent to be able to afford her desired retirement expenditures. But indeed, the actual MWR for the 1921 retiree was 9.78 percent. As another example, the 1966 retiree experienced the lowest MWR in history (4.08 percent). But with a 16.62 percent savings rate, the 1966 retiree accumulated wealth of 14.71 times final salary, which required that she only use a withdrawal rate of 3.4 percent to meet her retirement spending goals. Using the SAFEMIN savings rate was always sufficient to finance desired retirement expenditures regardless of the actual wealth it provided at the retirement date. The actual MWR, which could not be known until 30 years after retirement, was always at least as high. The year that the required and actual withdrawal rates were the same, which was 1918, defines 16.62 percent as the SAFEMIN savings rate.

Potential Tragic Consequences of the Traditional Retirement Planning Approach

The traditional retirement planning approach, represented here as targeting a wealth accumulation at retirement equal to 12.5 times final salary, has potentially tragic consequences. Using the SAFEMIN savings rate that worked in every historical circumstance, Figure 6 provided a basis for determining that in 59 percent (65 out of 110) of the historical rolling 30-year work periods, the retiree had accumulated wealth less than 12.5 times final salary. In 15 cases, accumulated wealth was even less than 8 multiples of final earnings. Though the SAFEMIN savings rate was shown to always have worked, these seemingly low wealth accumulations may have discouraged someone from continuing to save, or may have caused someone to needlessly delay retirement.

On the other hand, in recent years, wealth accumulations have been high. They exceeded 12.5 times final earnings between 1996 and 2008. Those saving for retirement during this time may have achieved traditional wealth targets earlier than expected, which may have caused people to either cut back on their savings or even retire early, while unbeknownst to them, post-retirement market conditions could have resulted in a lower-than-expected sustainable withdrawal rate. This is a particular concern for recent retirees who may be overly reliant on the notion that a 4 percent withdrawal rate is safe.

Pfau (2010b, 2010c, and 2010d) provides a trio of studies that each use a different methodology to question the safety of the 4 percent rule, especially for retirees from the past decade. Pfau (2010b) investigates safe withdrawal rates in 17 developed market countries between 1900 and 2008 and finds that even with unrealistically favorable assumptions, the 4 percent rule provided safety only in 4 of the 17 countries. Pfau (2010c) shows that retirees in 2000 are exhausting wealth in the 10 years after their retirement at a faster pace than any previous retirees, at least in nominal terms. Pfau (2010d), which extends earlier work by Bennett and Russell (2007), predicts that maximum sustainable withdrawal rates for recent retirees will fall below 4 percent based on regression results using market valuation and yield measures.

The current study indicates, though, that recent retirees will have had the opportunity to fare better had they used the “safe savings rate” approach. Figure 6 shows that between 1996 and 2008, the required withdrawal rates to meet spending goals after using a 16.62 percent savings rate were less than 4 percent. The unprecedented bull market of the 1990s would have allowed the 2000 retiree to finance her planned retirement expenditures using a withdrawal rate of only 2.62 percent. It is worth mentioning again that just as Bengen’s SAFEMAX is derived from past data and future retirees (those retiring since 1980 whose 30-year MWRs are still unknown) could experience conditions that lead to a lower SAFEMAX; the SAFEMIN savings rate could also eventually be increased as a result of the experiences of post-1980 retirees. As long as the actual MWR will be above 2.62 percent, then the 2000 retiree following these guidelines will succeed. At least, should the MWRs for recent retirees fall dramatically below 4 percent, the consequences of having followed this new approach to retirement planning will be less tragic than following the traditional retirement planning approach.

SAFEMIN Savings Rates with Varied Assumptions

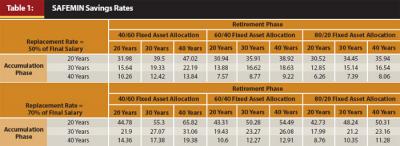

As the concept of “safe savings rates” is not one-size-fits-all, Table 1 provides a brief introduction to show how the SAFEMIN savings rate varies based on assumptions about asset allocation, replacement rates, and the duration of the accumulation and decumulation phases. The most important feature of the table is the overwhelming importance of starting to save early. For the baseline 60/40 asset allocation, 30-year retirement, and 50 percent replacement rate, someone saving for 40 years can enjoy a SAFEMIN savings rate of 8.77 percent, compared with 16.62 percent for 30 years of saving and 35.91 percent for 20 years of saving. Also, SAFEMIN savings rates naturally increase as the retirement duration increases, but the table shows that the rate of increase is much less than observed for changing accumulation phase durations. From the baseline case, increasing the retirement length from 30 to 40 years causes the SAFEMIN savings rate to increase from 16.62 to 18.63 percent.

Increasing the replacement rate to 70 percent also leads to significant increases in SAFEMIN savings rates compared to the 50 percent baseline. And lastly, more aggressive asset allocations allow for a smaller SAFEMIN savings rate, though this type of feature is generally true for studies based on U.S. historical data. This does not necessarily imply that higher stock allocations will be a good idea for conservative investors in the future.

On the issue of asset allocation, higher stock allocations have tended to provide higher expected wealth and a higher probability for reaching a particular wealth accumulation goal. However, Pfau (2010a and 2011a) demonstrates that when considering wealth accumulation in a utility maximizing framework that places more weight on avoiding extremely low wealth accumulations, risk-averse investors may favor decreasing stock allocations near retirement. Looking forward, financial planners and their clients must consider whether they will be comfortable using higher stock allocations based on the impressive and perhaps anomalous numbers found in past U.S. data, particularly as the United States is currently experiencing low dividend yields and high cyclically adjusted price-earnings multiples.

Conclusion

This study can be interpreted as providing a resolution to the “safe withdrawal rate paradox,” which David Jacobs (2006) and Michael Kitces (2008) developed independently. Consider the following: at the start of 2008, Person A and Person B each have accumulated $1 million. Person A retires and with the 4 percent rule is permitted to withdraw an inflation-adjusted $40,000 for the entirety of her retirement. In 2008, both Person A and Person B experience a drop in their portfolio to $600,000. Person B retires in 2009, and the 4 percent rule suggests he can withdraw an inflation-adjusted $24,000. The paradox is that these seemingly similar individuals experience such different retirement outcomes.

To resolve the paradox, I suggest we shift the focus away from the safe withdrawal rate and toward the savings rate that will safely provide for the desired retirement expenditures. Had both of these individuals saved in accordance with the “safe savings rate,” they would both likely be able to withdraw the same desired amounts, even though they would be using different withdrawal rates.

This research provides a simple scenario to illustrate the principle of the “safe savings rate.” Introducing more realistic factors could either increase or decrease required savings rates. Safe savings rates could be lowered, for example, by extending the approach introduced by Guyton (2004), if one is prepared to follow dynamic strategies that either increase future savings rates, delay retirement, or decrease retirement expenditures in response to market conditions. As well, Pfau (2011b) demonstrates that long-term investors may be able to improve risk-adjusted returns by using a dynamic asset allocation strategy that responds to stock market valuations, and such an approach could possibly allow for reduced savings rates. Including other financial assets such as small-capitalization stocks, international stocks and bonds, Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, and real estate, for example, provides more diversification and may lower required savings rates. Savers who already hold wealth at the beginning of their career can also enjoy lower savings rates (more generally, this factor can be applied for individuals wishing to adopt this approach when already in mid-career).

On the other hand, the “safe savings rate” found here may be too low for reasons beyond the assumed career length and desired spending needs. For example, I excluded portfolio management fees to be consistent with most existing research, but simply introducing a fee of 1 percent of assets deducted at the end of each year would increase the baseline scenario’s safe savings rate significantly from 16.62 percent to 22.15 percent. As well, many investors will wish to use life-cycle asset-allocation strategies that reduce the stock allocation based on age. Pfau (2010a and 2011a) shows the potential importance of these strategies in reducing risk during the accumulation phase, though Table 1 indicates that lower stock allocations will result in high required savings rates.

Revisions to the safe savings rate must also be considered with respect to uncertainties about future salary and retirement spending needs. Individuals may wish to save more out of concern for the possibility that future disability or unemployment will inhibit future savings opportunities, or to otherwise plan for an even worse worst-case scenario for asset returns than provided thus far by history. The study also lowers the “safe savings rate” artificially by assuming a constant real salary for the baseline scenario. Most workers experience lower wages early in their career, which will lessen the chances for compounding returns, and if they wish to replace a certain percentage of an otherwise higher final salary, they will also require more savings.

Research is also needed to allow for variable savings rates designed to smooth consumption in the manner described by Kotlikoff (2008). The savings rate does not need to be fixed, as individuals can make projections for their future income, unique consumption needs such as raising children or paying for a home, and retirement expenditures. Allowing for consumption smoothing needs, these projections can be calibrated with a variable savings rate needed to fit the planned pattern of lifetime savings. Lastly, this research has implications for Monte Carlo analysis of retirement planning, as many simulations assume that asset returns are independent over time (not serially correlated). The historical data suggest that this assumption has not been the case, and research using actual historical return sequences may be better suited for long-term retirement planning studies.

References

Bengen, William P. 1994. “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data.” Journal of Financial Planning 7, 4 (October): 171–180.

Bengen, William P. 2006. Conserving Client Portfolios During Retirement. Denver: FPA Press.

Bennett, Rob, and John Walter Russell. 2007. “The Retirement Risk Evaluator.” Available from www.passionsaving.com/retirement-calculator.html.

Guyton, Jonathan T. 2004. “Decision Rules and Portfolio Management for Retirees: Is the ‘Safe’ Initial Withdrawal Rate Too Safe?” Journal of Financial Planning 17, 10 (October): 54–62.

Jacobs, David B. 2006. “Is Failure an Option? Designing a Sound Withdrawal Strategy.” Unpublished draft paper (October).

Kitces, Michael E. 2008. “Resolving the Paradox—Is the Safe Withdrawal Rate Sometimes Too Safe?” The Kitces Report (May).

Kotlikoff, Laurence J. 2008. “Economics’ Approach to Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 21, 3 (March).

Pfau, Wade D. 2010a. “Lifecycle Funds and Wealth Accumulation for Retirement: Evidence for a More Conservative Asset Allocation as Retirement Approaches.” Financial Services Review 19, 1 (Spring): 59–74.

Pfau, Wade D. 2010b. “An International Perspective on Safe Withdrawal Rates from Retirement Savings: The Demise of the 4 Percent Rule?” Journal of Financial Planning 23, 12 (December): 52–61.

Pfau, Wade D. 2010c. “Will 2000-Era Retirees Experience the Worst Retirement Outcomes in U.S. History? A Progress Report After 10 Years.” Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper #27107 (November).

Pfau, Wade D. 2010d. “Predicting Sustainable Retirement Withdrawal Rates Using Valuation and Yield Measures.” Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper #27487 (December).

Pfau, Wade D. 2011a. “The Portfolio Size Effect and Lifecycle Asset Allocation Funds: A Different Perspective.” Journal of Portfolio Management 37, 3 (Spring): forthcoming.

Pfau, Wade D. 2011b. “Revisiting the Fisher and Statman Study on Market Timing.” Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper #29448 (March).