Journal of Financial Planning: May 2011

If financial planners want to know what’s keeping their older clients up at night, they might consult the 2010 Age Wave study sponsored by Genworth Financial, “Our Family, Our Future: The Heart of Long-Term Care Planning.”1 While the recent decade of economic crises has caused numerous financial anxieties, the number one worry of retired Americans is uninsured health-care costs.

The fear relates more to their families than to themselves. According to the study, the respondents’ greatest fear regarding the possibility of a long-term illness is not running out of money (10 percent), or dying (11 percent), or ending up in a nursing home (26 percent). The overwhelming fear is “being a burden on my family” (53 percent). Gerontologist and author of this study (and numerous books), Ken Dychtwald, Ph.D., president and CEO of Age Wave, has captured the weight of this issue in what is becoming an Internet-famous quotation: “[The] caregiving burden is the single most devastating social, economic, and spiritual sinkhole of the early decades of the 21st century. It could be a death blow to our thriving culture and economy.”

What can financial planners do for their retired clients? According to Jesse Slome, executive director of the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance in Los Angeles, a planner has three options for addressing clients’ long-term care needs. First, recommend solutions yourself by gaining expertise in the various types of long-term care insurance (LTCi) products available. Second, partner with local LTCi professionals to take advantage of their knowledge, to access solutions and products from multiple insurers, and to keep pace with ever-changing health insurance underwriting standards. Third, do nothing.

Regarding the “do nothing” alternative, Slome calculates a financial planner’s potential loss of income assuming clients over age 65 draw down assets under management to pay for five years of long-term care. He notes that 40 percent of people over 65 will need two or more years of long-term care with half of those needing care for more than five years.

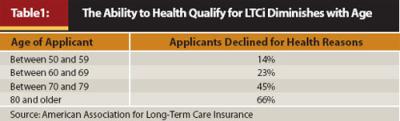

However, despite his belief in the efficacy of LTCi, Slome offers one caveat. There is an inherently limited market for LTCi for a number of reasons. First, the average age of purchase of an LTCi policy is 57, and the ability to health qualify for coverage diminishes with age (see Table 1).

Second, there are financial limitations to coverage: applicants must be able to afford increasingly expensive coverage (detailed in the next section). Third, there is a subtle marketing issue limiting the purchase of LTCi. Most Americans do not know people who have benefitted from these policies and are hesitant to purchase a product with which they are unfamiliar. Currently only 15–18 million Americans own long-term care products. That caveat stated, the odds of doing nothing can be catastrophic for clients who cannot afford to lose a few hundred thousand dollars.

Crisis Among LTC Insurers

Aside from what’s keeping your retired clients awake at night, planners need to be cognizant of what’s keeping long-term care insurers awake at night. According to Christine Schuster Khemis, CLTC, of LTC Financial Partners LLC in Mill Creek, Washington, there has been a significant shake-up among LTCi carriers, with major companies either leaving the market, staying in the market, or coming back into the market.

The problem for insurers lies in recent changes to old assumptions. Insurance companies used to rely on shorter longevity rates, larger policy lapse assumptions, and greater investment returns. Things have changed, says Khemis: “People are living longer, they are not letting their LTCi policies lapse (the old 5 percent-plus lapse assumption has been replaced by a 1–2 percent actual lapse experience), and the insurers are not making near what they used to on their fixed-income investment portfolios.”

For Slome, the LTCi industry has all the makings of the perfect storm—historically low investment returns matched with historically high benefit claims. In a report released January 31, 2011, Slome found the nation’s 10 leading long-term care insurance companies paid more than $10.8 million in daily claim benefits in 2010, a 53 percent increase in payments from 2007, when the same companies paid $7 million in daily benefits.

MetLife stopped selling new traditional LTCi products in November 2010. Transamerica stopped selling new policies for a while but is coming back into the LTCi market. Genworth Financial and John Hancock, the industry’s two largest insurers, are requesting rate hikes that in some instances are in the 40 percent-plus range. As Slome notes, “Rate increases create negative headlines, but in the end only 1 percent of policyholders drop their coverage as a result, a clear indication that policyholders understand the risk and value of their purchase.”

Newer policies are more expensive and older policies are suffering significant rate increases for the same coverage. According to data from the 2011 Long-Term Care Insurance Price Index published by the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance, a 55-year-old couple purchasing long-term care insurance protection can expect to pay $2,350 a year (combined) for about $338,000 of combined current benefits, which will grow to about $800,000 of combined coverage when the couple turns age 80. If a couple (assuming preferred health discount) age 60 or 65 applied for the same insurance protection, annual premiums would increase to $3,395 and $4,075, respectively (benefits at age 80 obviously decrease in value the later they purchase the policy).

Not only are premiums becoming more expensive but the types of benefits are shifting. Says Slome, “I call it LTCi nursing home avoidance insurance. Most people want to get care at home.” His statistics back up this notion. The association’s 2010 LTCi Sourcebook finds that 31.0 percent of new individual claims are for home-care services, 30.5 percent are for assisted living, and 38.5 percent are for skilled nursing home care.

Types of Long-Term Care Covered by Policies

Today, almost all policies are comprehensive. According to Betty Doll, CLTC, of Doll & Associates Long-Term Care Insurance Services in Asheville, North Carolina, these comprehensive policies provide numerous options. Unfortunately, even the alternatives to nursing home care are not cheap. A brief review of care options follows; annual costs are from the “Genworth 2010 Cost of Care Survey.”

- Home care is appropriate at the custodial and non-skilled care levels. Skilled care with a home health registered nurse or therapist can be provided in the home, but may be very expensive. A Medicare-certified home health aide who provides assistance with bathing and dressing and other non-medical services has an average annual cost of $43,472. Notes Doll: “This cost represents the average amount that is paid for home health care; some families are paying for two hours a day, some 24 hours per day. Usually the cost of 8–10 hours of home care is roughly equivalent to the cost of a day in a skilled nursing facility.”

- Adult day-care facilities offer custodial care during the weekdays (and some on weekends) for people with moderate impairments requiring minimal assistance. Adult day-care centers provide much-needed respite care for family caregivers. The annual median cost for these services (5 days a week) is $15,600.

- Assisted living facilities (or ALFs) are residential facilities (usually apartments) providing non-skilled care for people who need help with their activities of daily living (ADLs) but who can provide much of their own care with minimal assistance. Usually, skilled care is not provided in assisted living facilities, although services to those who need supervision because of cognitive impairment are often covered. Meals are usually provided in a community dining room. The annual median cost for a one-bedroom, single-occupancy ALF is $38,220.

- Skilled nursing facilities entail two separate components. The first provides skilled nursing care that may be covered by Medicare (if the care meets the criteria Medicare sets forth). The second provides non-skilled (or custodial) care. The goal of the Medicare component is to rehabilitate patients so they can return home; however, patients often are unable to return home and are moved to the non-skilled or custodial section of the facility. The annual median cost of a semi-private room in a nursing home is $67,525 and the cost of a private room is $75,190.

Reducing the Cost of LTCi

Khemis notices two growing trends in the LTCi universe—the increased use of hybrid products and the popularity of single-premium LTCi. In the single-premium scenario, clients take poorly performing assets (for example, low-interest CDs or underperforming stocks) and make a one-time investment in an LTCi policy.

Although the experts interviewed for this article emphasize the importance of buying LTCi at an early age to reduce lifetime costs, they also highlight the following vehicles as safe paths to save on LTCi coverage:

- Employer-sponsored plans

- Options and riders in traditional plans

- New hybrid products on the market

Employer-Sponsored Plans. For Khemis, the cheapest way to obtain LTC coverage is often through employer-sponsored plans. These plans have advantages not offered to individual policyholders in the form of (1) lifetime discounts, (2) underwriting concessions, and (3) tax advantages. Business owners who purchase long-term care insurance for themselves and/or their employees may deduct a portion of their premiums.

“Specific laws and regulations apply, but these tax advantages can prove especially valuable for shareholders and partners of sub-S and C-corporations and limited liability companies,” Khemis explains. In addition, businesses can purchase LTC coverage for owners and key employees as part of a special compensation package that does not require the company to buy LTCi for 100 percent of their employees.2

Options and Riders with Traditional LTCi. According to Khemis, the three most popular LTCi riders she sees in the current market are: (1) the waiver of the elimination period for home health care (the small premium increase for this waiver saves out-of-pocket dollars in a big way), (2) the shared care rider (couples share and inherit each other’s unused LTCi benefits tax free), and (3) the inflation-protection rider, which is capped at a maximum of 5 percent. Many clients reduce their premiums by dropping that inflation percentage from 5 percent to a lower number.

While calculating for consumers how they can make LTCi more affordable, Slome is a firm believer that some coverage is better than no coverage. He reiterates: “LTCi is not an investment, it’s insurance! It’s personal, not financial.” So personal, in fact, that Slome has witnessed several “millionaire next door” types literally starving themselves to death in order to avoid running out of money and be able to pass on their assets to their children.

Slome recommends the following policy changes to make LTCi more affordable for clients:

- Save 42–50 percent on LTCi premiums by buying a three-year policy or 30–34 percent by buying a five-year policy, as opposed to buying an unlimited-term policy

- Save 10–25 percent on premiums by adding a 90-day elimination period rider (a larger deductible) versus a 30-day elimination period rider, and save an additional 10 percent by stretching the elimination period to 180 days

- As noted by Khemis above, save anywhere from 10–40 percent on premiums when a couple can take advantage of the spousal and partner discount

- Save 10–25 percent by purchasing coverage at a younger age, when clients still health qualify for the preferred health discount (the preferred health discount is never lost once it is locked in)

Hybrid Products. Hybrid products come in two basic flavors, annuities with LTC riders and life insurance with LTC riders. According to data from LIMRA, life-LTC hybrid sales have risen, with premiums reaching $813 million in 2009, up from $633 million in 2008. Comparatively, new premiums for traditional LTC insurance have declined to $464 million in 2009 from $602 million in 2008. The life-LTC hybrid products provide a payout to clients either in the form of a death benefit or LTC coverage. Annuity-LTC hybrid products offer similar alternative payouts.

However, advisers and their clients should beware not to view employer-sponsored plans or hybrid products as automatic panaceas. According to Catherine Theroux of LIMRA, “Hybrid and employer-sponsored (group) long-term care insurance coverage are not in themselves less expensive. People with these products tend to have coverage that is not as rich as those who own individual LTCi.”

Examples: Comparing Hybrid Products

Betty Doll ran the numbers on two scenarios to illustrate use of major hybrid products vis-à-vis traditional LTCi products. Doll notes that people who purchased LTCi years ago without an inflation rider (for example, a policy paying a maximum of $100 a day) may consider buying one of the two following products to supplement their existing traditional policy. She adds that either the life or annuity hybrid will work well for clients opposed to the “use it or lose it” character of traditional insurance.

Life Insurance with LTC Rider. Assume a 70-year-old couple purchases a single premium, second-to-die life insurance policy with $120,000 dollars, resulting in a death benefit of $212,400. This $212,400 is the first money that would be paid out if long-term care is needed. When the policy is purchased, the clients also have the option to buy a “continuation of benefits rider” (COBR) that will continue to pay for care if the death benefit is exhausted. This 70-year-old couple would pay an additional annual premium of $1,120 for this rider, which would pay for care for an additional 50 months.

If neither spouse ever needs care, at the death of the second spouse, the policy would pay $212,400 to the named beneficiary. If only a brief amount of care is needed, the benefits paid would be subtracted from the $212,400 and the beneficiary would receive the remainder. Either way, the full $212,400 is received either to pay for care or as a death benefit.

If care is needed by one or both of them, the life insurance policy pays out 2 percent ($4,245) of the death benefit for 50 months of care. If the care needed for one or both of them exceeds 50 months, the COBR pays $4,245 per month for an additional 50 months. There is no death benefit for funds not used from this continuation of benefits rider. The cash surrender value of this policy is never less than the initial contract premium, and this contract is currently earning 4 percent. Note that there are several varieties of life-LTC contract.

Annuity with Long-Term Care Rider. Assume a 70-year-old couple purchases a single-premium $120,000 fixed annuity. Funding can come from a 1035 exchange of an existing (non-qualified) annuity, from an existing life insurance contract, or from existing “emergency funds.” Note that these policies must contain specific tax-qualified LTC language. A key benefit to this approach is that funds taken from the annuity to pay for care and the funds from the COBR are received tax free. Using a 1035 exchange allows a policyholder to receive cash accumulation in an existing annuity tax free if used to pay for needed care.

As with the life-LTC option, a COBR can be purchased to pay for care beyond what could be paid from the funds in the annuity. If care is never needed, funds in the annuity go to the beneficiaries. The policy can also be annuitized at any time, however the LTC benefit is then forfeited.

If care is needed, the annuity pays out in equal increments over a fixed period—usually three years. If the $120,000 annuity has grown in value to $150,000, it would pay $4,166 for the first 36 months of care. If the care needed exhausts the funds in the annuity, the benefits purchased in the COBR would then start paying out.

Regarding these two hybrid products, note that in the past the tax code (IRC § 1035) allowed a life insurance policy to be exchanged tax free for another life insurance policy or for an annuity contract. The Pension Protection Act of 2006 (PPA) changed the rules to permit both life insurance and annuity contracts to be exchanged for long-term care contracts beginning in 2010.

Government Intervention

One of the major benefits of health-care reform for long-term care is the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports Act (CLASS). According to Carol Harlow, CFP®, director of government relations for FPA of Miami-Dade: “Although the insurance industry lobbied hard against the inclusion of CLASS in the bill, it may provide more awareness of the products in the private marketplace. It may actually bring in healthier middle-aged people.”

Premiums and benefits for CLASS have not been established yet; the secretary of Health and Human Services must release the details of the plan by October 1, 2012. But some industry experts are already skeptical. Doll agrees the program may increase awareness, but states, “CLASS is a bad deal if you’re medically able to qualify for more affordable private coverage.” According to the actuaries at both the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the American Academy of Actuaries, in this voluntary program, working individuals are projected to have an average of $150 to $240 a month (based on age) automatically deducted from their paycheck—note that these rates are not set at this time, and experts in the field believe the ultimate price will depend on how many Americans participate in the program. After paying premiums into the program for a minimum of five years, those who have contributed and have remained enrolled in the program are covered if they face an LTC event. Cash reimbursement benefits are expected to be somewhere between $50 and $75 a day, but again, these are speculative estimates, as true rates have not yet been determined.

Khemis is equally skeptical, but a bit more philosophical about CLASS. She does agree with Harlow that the provision “increases awareness” of LTCi products. It helps educate both employers and employees about LTCi. In addition, it may be the only solution available for working people with disabilities who may not health qualify otherwise and need the guaranteed issue. However, Khemis sees three specific negatives about the provision. First, it can only be used by workers, not by retirees. Second, it entails a five-year vesting period. As she quips, “You don’t want to get hit by a truck in your fourth year of premium payments!” And third, not only are the payout rates vague at this point, but they likely will be very low when compared with the average cost of care—in the neighborhood of $200 a day.

One government program both women find more enticing is the Long-Term Care Partnership Programs now available in more than 30 states (in 1987 this program was only available in four states). Khemis applauds this agreement between the public and private sectors, whereby those LTCi policyholders who exhaust their LTC benefits have the option to go on Medicaid without spending down all of their assets. The LTCi carrier sends a letter to its state Medicaid office to initiate this action.

Doll likewise sees these programs as a good deal for the middle class—“A safety net with no downside,” as she observes. Furthermore, for people under age 75, all partnership policies are required to have inflation riders (depending on the policyholder’s age).

Many experts agree that LTCi is especially important for women. As Khemis notes in Dignity for Life: Facts That Can Protect Your Assets and Quality of Life,

- Women are often caregivers to their husbands

- Women have a longer life expectancy and may outlive their spouse or partner

- Women can find themselves with depleted assets due to a spouse’s need for long-term care

- Women make up two-thirds of the people in nursing homes

Slome agrees that LTCi is a particularly great buy for single women. As he notes: “While 66 percent of LTCi are paid to women, LTC insurance is based on unisex rates—single women pay the same rates as single men!” And they live five years longer on average, Slome adds. He asks rhetorically, “How many planners tell women this story about LTCi?”

This fact alone leads Slome to assert that most financial planners need to partner with a specialist in order to best serve their clients. Doing nothing is not a serious option, and trying to stay abreast of all the changes in premiums, riders, options, and underwriting is a truly gargantuan task. His advice? Keep studying, and consider partnering with a professional in the long-term care field.

Jim Grote, CFP®, is a financial writer whose articles have also appeared in Bloomberg Wealth Manager, Family Business Review, Financial Advisor, MorningstarAdvisor.com, and Planned Giving Today. He can be reached at jimgrote@hotmail.com.

Endnotes

1. Available at www.agewave.com/research.

2. “Prudential Long-Term Care Insurance 2011 Tax Treatment—Quick Facts.” Available at www.massagent.com/insmarkets/Prudential% 202011%20Tax%20Guide%20for%20Long%20Term%20Care%20Insurance.pdf.